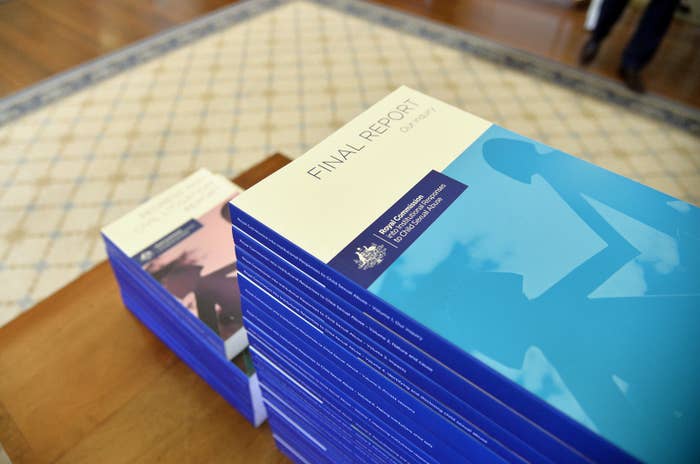

Thousands of stories, and statistical insights, about Australians who suffered as children at the hands of sexual abusers have come to light in the 1000-plus page, 17-volume final report of Australia's Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Childhood Sexual Abuse, handed down on Friday.

The report paid tribute to the bravery of survivors for speaking out, in more than 8,000 private hearings, about what had been done to them, and the destruction and chaos it had wrought upon their lives.

"Many spoke of having their innocence stolen, their childhood lost, their education and prospective career taken from them and their personal relationships damaged," the report said. "For many, sexual abuse is a trauma they can never escape. It can affect every aspect of their lives."

The commissioners wrote that without the personal stories of survivors they could not have done their work.

"These stories have allowed us to understand what has happened," the report said. "They have helped us to identify what should be done to make institutions safer for children in the future.

"The survivors are remarkable people with a common concern to do what they can to ensure that other children are not abused. They deserve our nation’s thanks."

The report published statistics based on the experiences, where information was available, of 6,875 survivors who testified at the commission up to May 31, 2017.

It found that the majority of survivors (64.3%) were male.

More than half said they were aged from 10 to 14 when they were first sexually abused.

Female survivors tended to be younger when they were first sexually abused than male survivors.

14.3% of survivors were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

4.3% of survivors said they had a disability at the time of the abuse.

3.1% of survivors were from culturally or linguistically diverse backgrounds.

93.8% of survivors said they were abused by a man.

83.8% of survivors said they were abused by an adult.

10.4% of survivors were in prison at the time they gave evidence to the royal commission.

The average duration of child sexual abuse in institutions was 2.2 years.

36.3% of survivors said they were abused by multiple perpetrators.

These stories were told in private sessions, with one or two commissioners present to give survivors as safe as possible an environment to share their distressing and traumatic stories.

Almost 4,000 of those stories have been published with the final report in the form of short, de-identified narratives.

One published narrative was about "Keenan", an Aboriginal man who was abused as a child and has spent most of his adult life in prison.

He is one of the 10.4% of survivors who spoke to the commission from prison, where he was serving a lengthy sentence for attacking a man he thought was a paedophile.

"I’ve got a deadset hatred of sex offenders," he told the commission. "An absolute hatred."

Keenan told the commission that he was fostered by a "nice white family" in the mid-1980s when he was five, who he loved and who became his adoptive parents. But he felt different in the white neighbourhood as an Aboriginal child: "I was a bit worried about what people would think when my family is white and I was black."

He started going to the local Catholic church when he was nine to learn about Holy Communion. It was here that the parish priest took an interest in him.

"He asked my parents if he could do private studies with me at the church and my parents thought, you know, the sun shined out of his arse, they thought he was the top bloke," he said.

The priest abused Keenan when they were alone together, touching Keenan's thigh and penis. Keenan said he didn't want to do it, but the priest "roared" at him that no matter what he told his parents, they wouldn't believe him.

After two more instances of abuse, Keenan tried to tell his father about what was happening, but was dismissed. "No, you’re probably looking at it the wrong way. He’s probably just mucking around with you".

Keenan refused to go back to see the priest, and changed churches. The abuse shattered him — he lost faith in God, and felt betrayed by his father.

"The two main things I believed in the strongest weren’t there for me," he said.

After that, Keenan decided to suppress the abuse, saying: "I'll find a little part of my body I can fold it up into and I don’t have to talk about it anymore."

But as with so many survivors, it dramatically changed the course of Keenan's life. He said he became "a prick of a kid" and at 15 moved out of home with a girlfriend and lost touch with his adoptive family for years. In the ensuing years, he wound up in juvenile detention and later adult prison.

Keenan told his girlfriend about the abuse, and she was supportive. In his mid-20s, he told his mother, and she was upset he hadn't told he earlier. His relationship with his father remained difficult.

Other than those conversations, sharing his story with the commission was the first time Keenan had spoken about the abuse in 30 years.

"Even now in court they asked if I’ve been touched as a kid I said 'No'. ‘Cause it’s got nothing to do with them. It’s taken me a long time to talk about this. Opening up again today about it, it makes me feel like I’m a kid again. It’s bringing back a lot in my mind I’ve learnt how to put away," he said.

"At the age I am now I’ve got to get rid of that burden that’s sitting inside me, I think that’s the thing that keeps bringing me back to jail. ‘Cause jail’s a good place to hide."

The support services page for the Royal Commission is here. If you or someone you know needs help, you can call 1800 Respect (1800 737 732) or visit www.1800respect.org.au, or contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit www.lifeline.org.au.