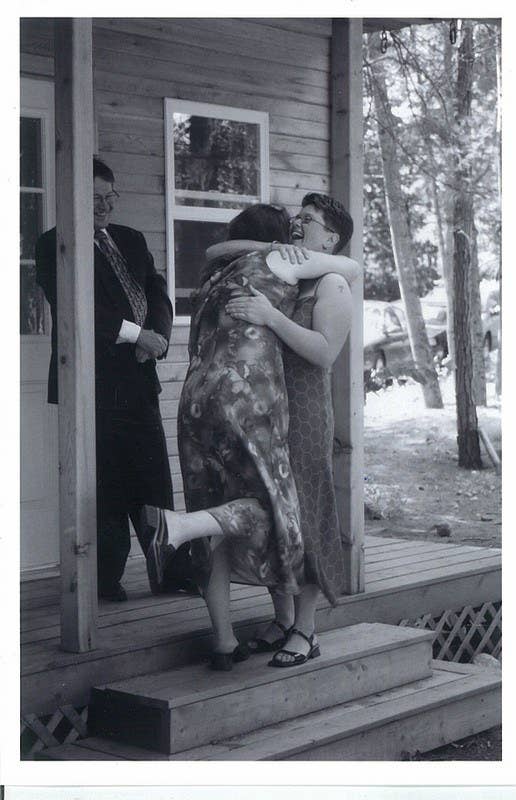

Corin was 10 months old when his mums got married on the shores of Lake Catchacoma in Ontario, Canada. Instead of a bouquet, they carried him down the aisle.

It was 23 August 2003 and Ontario had changed the law to allow same-sex couples to marry just six weeks earlier. Corin's mums, Jacqui Tomlins and Sarah Nichols, were driving through Nichols' hometown of Toronto when they heard the news on the radio.

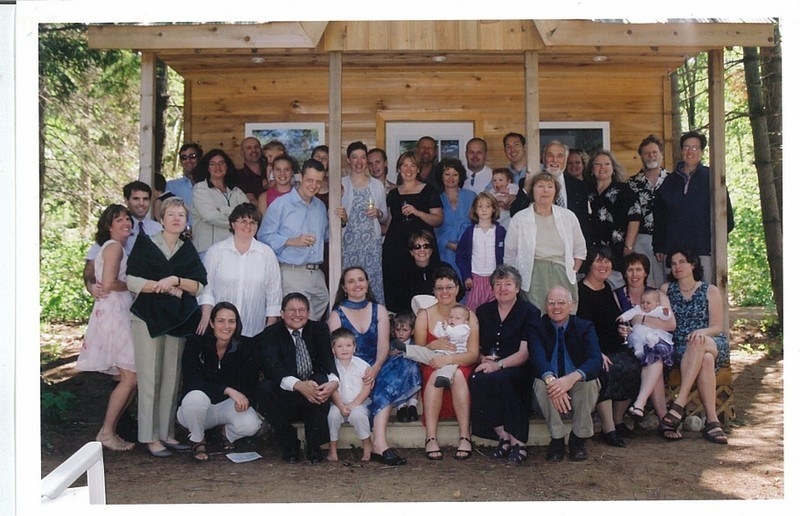

It wasn't the most romantic of proposals – "We could get married! I mean, do you want to get married?" – but six weeks later, family and friends from across the world gathered at Lake Catchacoma to watch them carry Corin down the aisle.

Fast-forward 13 years to the Nichols-Tomlins household in Kew, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. Tomlins is sitting on a couch in their sunny living room and Nichols is on the floor, sitting up against the floor-length windows. Outside, Corin, now 13, is playing with the family dog while their two daughters, Scout and Cully, wander in and out.

Tomlins tells BuzzFeed News she specifically remembers having a discussion about when Australia might follow Canada's lead.

"I remember saying that five years seemed too short," Tomlins says. "It was not on anybody’s radar back then. It really was not an issue at all. But 10 years, maybe, seemed realistic."

"Now we’re up to what, 13?" Nichols adds. "And it could be 14, 15, 16."

Back when Nichols and Tomlins married, "traditional" marriage was not defined in the Marriage Act. That's not to say marriage was a free-for-all – rather, the definition rested in common law, instead of legislation.

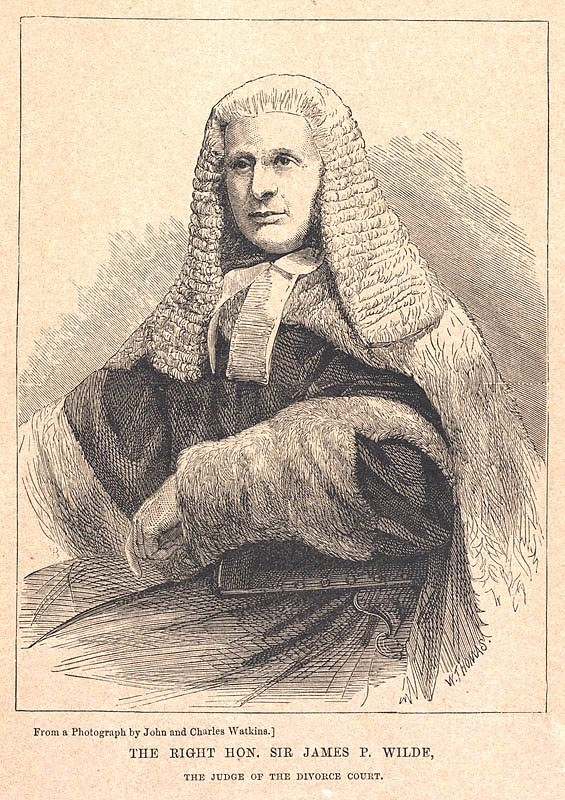

The common law came from a landmark case in England in 1866, known as Hyde vs Hyde and Woodmansee, that had nothing to do with same-sex couples.

Instead, it addressed a spat over polygamy, adultery, and Mormonism between a separated husband and wife. In his findings, Lord Penzance defined marriage as "the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all

others".

The definition stuck.

After returning to Australia, Nichols and Tomlins were introduced to Jason and Adrian Tuazon McCheyne by a mutual friend. Also from Melbourne, the Tuazon McCheynes had married at the Toronto City Hall on 5 January 2004.

The couples shared a city, a Canadian wedding, and a question: Is our marriage legal here?

To find out, they assembled a pro bono legal team and lodged an application in the Victorian Family Court, seeking a legal declaration about the validity of their marriages. A hearing was set for 23 August 2004 – exactly a year after Tomlins and Nichols had walked down the aisle.

Neither of the couples anticipated how the case would end up.

Countries including the Netherlands, Belgium, and, of course, parts of Canada had already started to legalise marriage equality by 2004. But elsewhere – like Ohio in the US – the tide was turning the other way, with governments moving to explicitly ban it to head off a predicted global tide. Australia's then prime minister, John Howard, was a staunch supporter of traditional family and marriage.

This context, paired with the two couples testing the laws in court, may have tipped Australia over the edge. On 27 May, Howard announced his intention to ban same-sex marriage in legislation.

"We've decided to insert this into the Marriage Act to make it very plain that that is our view of a marriage and to also make it very plain that the definition of a marriage is something that should rest in the hands, ultimately, of the parliament of the nation," he told journalists.

"[Marriage should] not over time be subject to redefinition or change by courts, it is something that ought to be expressed through the elected representatives of the country."

The bill, introduced on June 24, defined marriage as "the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life", and explicitly stated that international same-sex marriages were not valid in Australia.

It received support from the Labor opposition, and was opposed by just a handful of Greens and Australian Democrat MPs. On 16 August, the bill received royal assent – one week before the two couples were due to have their day in court.

Jason Tuazon McCheyne vividly remembers receiving a cheque in the mail from the Family Court – a refunded filing fee for his case, which now had no legal grounds to be heard. Nichols, a lawyer, had written to the court asking them to return the fee, given the government had literally changed the law.

The couples were stunned at the force with which the government had retaliated.

Tomlins recalls a now-prophetic conversation she'd had with Kristen Walker, a member of their legal team, at the time. One potential way the application could be thwarted, Walker advised, was if the federal government changed the law.

"I remember thinking at the time, That’s insane," Tomlins says.

"They’re not going to change the law because me and Sarah and Jason and Adrian have put in this little application to the Family Court. It seemed like it would have been a huge overreaction to something that we’d done.

"But of course, that’s exactly what they did do."

The complicated consequences of the two couples' actions in 2004 left them with lingering worries. Do they feel responsible for Howard changing the law?

"I’d be lying if I said I didn’t worry about that," says Jason Tuazon McCheyne. "Maybe if I had waited until after the election… Because suddenly it was an election year, it was used as election capital. Maybe if we had waited another year..."

He trails off, and starts again.

"We were trying to do the right thing. We didn’t want a public fuss. The Age did write an article. ‘Gay husbands’ – the first time that phrase appeared in the media here – 'to test their marriage in court'. We certainly did a bit of media but we were doing a soft push, we wanted to do the right thing. We thought we’d win."

"But you don’t know – unless you test things, you don’t know. We had a right to push. We had a right to agitate for change."

"I feel like we set out to change the law," Nichols says, "and we did, and we’ve been trying to undo it ever since.

"If it hadn’t been us, it would have been somebody else. But given they changed the law directly in response to our application, and said so, in Hansard, of course we felt responsible. I think we all felt very responsible."

Nichols adds that she thinks the explicit anti-gay nature of the law galvanised the community around the issue.

"It wasn’t going to affect a huge number of people, but I think because the government reacted so badly, so heavy-handedly, that it did make people go, ‘Fuck. Our government really doesn’t like us'," she says.

"In the long run, it advanced the cause. But at the time, absolutely, we all felt responsible. Not responsible in that we shouldn’t have done it – we should have. But responsible as in, well, we'd better fix that."

The families have been campaigning ever since. At the last federal election, Jason Tuazon McCheyne and Jacqui Tomlins topped the Victorian Senate ballot for the Australian Equality Party, running on a broad platform of equality for LGBTI Australians.

And a few weeks ago, Corin, now 13, travelled to Canberra with his mums to tell politicians he didn't want a plebiscite on marriage.

Leaning over the coffee table at their home in Kew, he reads aloud from a pamphlet circulated earlier this year that claimed children of same-sex parents will likely become mentally ill, unemployed drug abusers.

"It made me feel angry, that people would produce stuff like this without getting actual facts, or talking to someone who was gay or lesbian or had two mums or two dads," he says.

Tomlins and Nichols say the more they thought about the idea of a same-sex marriage plebiscite, the worse it seemed. Even if it is the quickest route, it's the wrong one, they say.

"I'm going to be fine in this debate," Nichols says. But she worries for her kids, for older and younger same-sex–attracted people, for transgender people, and for anyone who lacks the safety net she exists in.

"There are so many people in the community who will not be fine. It's not about me."

Unlike some couples who yearn for a ceremony on home soil, Tomlins and Nichols carry no such sentiment. They had their 2003 ceremony at Lake Catchacoma and, 13 years later, they just want it recognised.

"Will you get married here, if the law changes?"

"No," Nichols says. "We're already married."