In Australia, it feels like marriage equality is inevitable.

Spurred on by scenes of jubilant celebrations in Ireland and the U.S., same-sex couples down under are increasingly hopeful of reform. The public wants change, and advocates appear to be winning a long-running war of attrition against a diminishing opposition — but they’re not quite victorious yet.

As thousands of Australians turned rainbow on Facebook to celebrate marriage equality in the U.S. last month, perhaps the most significant development yet in the Australian campaign emerged: a new cross-party bill was in the works.

For the first time, members of parliament (MPs) from different parties across the political spectrum had banded together to introduce a bill legislating for marriage equality. The news was celebrated by the public, decried by marriage traditionalists and welcomed – albeit cautiously – by advocates.

The bill “ups the ante”, says Rodney Croome, national director of Australian Marriage Equality (AME), but it’s not a done deal yet. The numbers in the parliament remain close, and a vote could fall either way.

“People aren’t the problem, the problem is politicians,” Croome tells BuzzFeed News.

In fact, the majority of Australian people want marriage equality. Recent polls have indicated support for the reform sitting pretty at around 70%. This is considerably higher than the latest countries to have introduced same-sex marriage, such as Ireland and the U.S. Given this, it’s baffling to many why Australia has delayed marriage reform for so long.

A combination of Australian political culture, influence from religious groups and unenthusiastic prime ministers has contributed to the glacial pace of reform. And despite a swell of public support in the wake of the Irish referendum and the U.S. Supreme Court decision, the Australian parliament remains immensely more conservative on marriage equality than the public it represents. However, the cross-party bill, to be introduced to the parliament this August, is the most promising move yet.

The U.S. Supreme Court ended state bans on same-sex marriage on June 26, 2015.

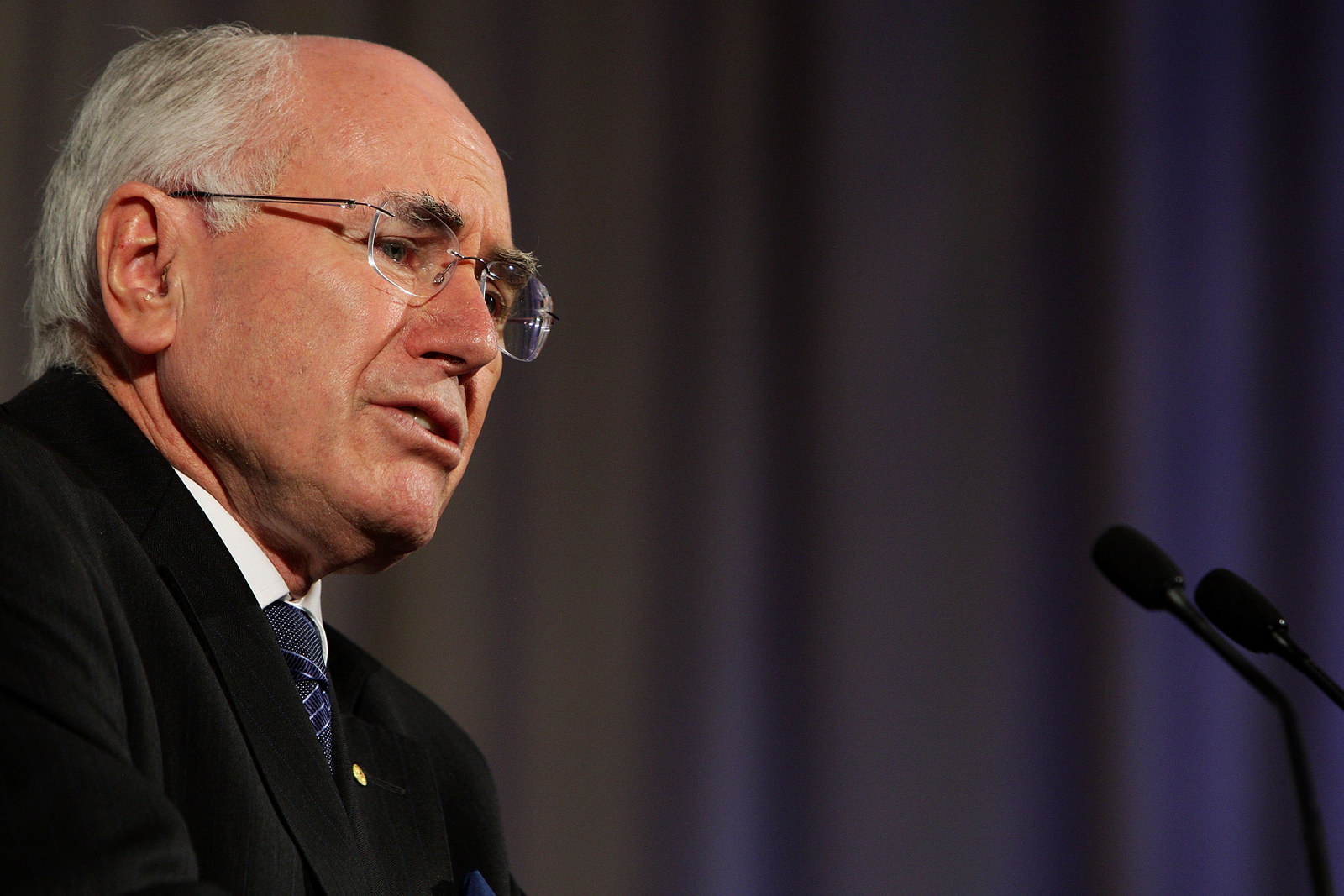

In 2004, the definition of marriage in Australia was not enshrined in legislation – only judge-made law. However, former prime minister John Howard (1996-2007) changed all that. Socially conservative and preoccupied with the traditional family, Howard was deeply concerned by the prospect of judges redefining marriage over time.

Countries including the Netherlands, Belgium, and parts of Canada had already started to legalise marriage equality by 2004. But elsewhere – like Ohio in the U.S. – the tide was turning the other way, with state governments moving to explicitly ban marriage equality in a safeguard against what they predicted might become a global tide. It came as no surprise that Howard, closely aligned with then-U.S. President George W. Bush, wanted to jump on this bandwagon.

And so, in 2004, the Australian Marriage Act 1961 was amended to add the phrase "marriage means the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life". The legislation passed Australia’s lower house without a single voice of dissent.

For a long time, Australia had no potent force pushing for marriage equality. But then in 2007, Howard’s 12 years of conservative, Liberal/National coalition government met a decisive end as centre-left Australian Labor Party rose to victory under new prime minister Kevin Rudd.

The next year, a sweeping range of federal reforms made same-sex de facto couples equal to opposite-sex de facto couples under Australian federal law. Eighty-five pieces of discriminatory legislation in tax, health and employment laws were removed, and the nature of the marriage equality campaign shifted. Instead of seeking marriage rights in order to gain rights as a couple, it was now a fight for the institution of marriage itself.

A major breakthrough came in 2011, when Labor changed its party platform to one in support of marriage equality. After a sustained push, advocates from the left wing of the party were able to splinter the more socially conservative right, succeeding in their efforts to change party policy with a resounding vote at the party’s national conference.

However, it wasn’t a complete victory for marriage equality advocates. Labor MPs were granted a “conscience vote”, meaning they did not have to vote along party lines. And despite the majority support within the party, a number of conservative MPs remained staunchly against the reform. The next year, a Labor-sponsored bill for marriage equality came to a vote in Australia’s lower house. It would have passed the House of Representatives had Labor bound on the issue, says independent New South Wales MP Alex Greenwich, who led AME at the time. Instead, it failed 98-42.

The strong result took marriage equality off the legislative agenda. And then an election loomed, the Labor party changed leaders for a second time and a relentless opposition labelled the government "chaotic” and “dysfunctional". The negativity worked – after six years of Labor rule, the 2013 election saw the Liberal/National coalition ushered back into government, under socially conservative prime minister Tony Abbott (who, incidentally, has a sister in a long term, same-sex relationship).

Graham Perrett, a Labor MP, told BuzzFeed News his party’s failure to introduce marriage equality in the six years they held government was a missed opportunity. “Labor is a broad church, but even in a broad church the walls have to start somewhere,” he said. “I would have thought that recognizing committed monogamous relationships would have been something that we did.”

As Australia transitioned back to a socially conservative government, polling showed public support for marriage equality continued to grow. A touching video of New Zealand’s lawmakers breaking out into a Maori love song after a successful vote for marriage equality made its way around the internet. England, Wales, Brazil, Uruguay and France all legalized same-sex marriage in 2013, too.

A big part of the growing support was heterosexual people starting to speak out in support of equality, says Croome. “For many years, our politicians heard from same-sex couples and their family members about why marriage equality matters. That was important, but it wasn’t sufficient," he says.

"MPs... are getting the mesage from heterosexual Australians that they care about this and they want it to happen."

Marriage equality was legalised in England in 2013, with the first same-sex marriages taking place the next year.

In December 2013, headlines across the world proclaimed that Australia now had marriage equality – which it did, kind of, for five days.

Hopes were raised when the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) government passed a regional law allowing same-sex couples to marry. However, less than a week later, it was challenged by the federal government and annulled by the High Court of Australia. After five whole days of wedded bliss, almost 30 couples had their marriages dismissed.

However, in the same ruling, the High Court said the federal government has power under the Australian constitution to legislate for marriage equality – a landmark moment in the Australian campaign. Crucially, the ruling dismantled any constitutional barriers to the federal government legislating same-sex marriage.

Now with the Australian public and the law onside, marriage equality became a parliament-focused waiting game of careful lobbying and cultural change. But with a conservative government in power, advocates – including Australian Marriage Equality, same-sex couples, and various MPs – were settled in for the long haul.

By the start of 2015, most of Australia’s natural allies, along with a number of European and South American nations, had all made the change. Reform was looming in Ireland and the U.S., but in Australia, other than a few stray private members bills being ignored in the parliament, the issue lacked momentum.

MPs and advocates have several theories as to why Australia held out amidst a tide of socially similar countries changing their laws. They say Australia’s leaders haven’t listened to the community, meaning they haven’t prioritised the popular reform. Critics also say governments have folded under the influence of religious groups.

Graham Perrett says it hasn’t been a priority for any prime ministers since Howard, and that has prevented movement. “A leader can stop progress or move their flock further forward,” he says.

Like Abbott, Perrett has a gay sibling – two, in fact. He’s spent a lot of time in parliament advocating for marriage equality, chairing a 2012 inquiry into the issue – which garnered more submissions than any inquiry in the history of federation – and co-convening the Parliamentary Friendship Group for LGBTI Australians.

“But I’m not doing it because my brothers are gay,” he says. “I’m doing it because it’s right.”

It’s personal for Greens senator Janet Rice, too. Her wife, Penny, is transgender, and if Penny wanted to change the sex on her birth certificate, they would be forced to divorce.

Rice pulls no punches in blaming the delay on groups like the Australian Christian Lobby, and the leadership of the Catholic Church. “It’s the completely out-of-proportion influence of the conservative Christian community on both the Labor party and the Liberal party.” MPs are scared of defying them, she says.

Lyle Shelton is the managing director of the Australian Christian Lobby, and perhaps the most potent anti-marriage equality lobbyist in Australia. He says the difference in opinion between politicians and the public is largely due to the Australian media pushing a pro-marriage equality agenda. The public don’t hear his side, he says.

“I can put out media releases all the time, and I do, and mostly they’re ignored. But I can go and sit in an MP’s office and give them the other side of the story,” he says. “I just think that politicians have to think a bit deeper than the public. And most parliamentarians can see through these popular polls.”

Shelton says Australia’s politicians have held out for so long because they see the ramifications of marriage equality. As Shelton sees it, this means stripping children of the right to have a mother and a father. Even though thousands of same-sex couples are already raising children in Australia, Shelton does not separate the issues of same-sex parenting and same-sex marriage. He argues that legalizing same-sex marriage would open the floodgates for commercial surrogacy and other ways of having children that Shelton sees as ethically sketchy.

Shelton says he opposes artificial reproductive technologies for all couples, not just same-sex couples. “It’s not motivated out of any animus towards same-sex attracted people at all,” he says. “But when you’re looking at public policy, public policy should always be in the best interests of the child.”

A May referendum on marriage equality saw 62% of Irish people vote yes. It was the first time a nation had introduced marriage equality based on a popular vote.

Come 2015, marriage equality had well and truly crept its way into Australia’s national consciousness. The usual marriage floats rolled down Sydney’s Oxford Street at the annual Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, but an anti-marriage equality advertisement scheduled to air the same night generated anger from the public. Channel Nine show Married At First Sight sparked a protest petition with thousands of signatures arguing the show was a slap in the face to same-sex couples who cannot legally marry. An AME campaign led to Australian corporations publicly backing the movement in great numbers.

And then Ireland happened.

The successful referendum in May made waves in Australia, reinvigorating the marriage equality campaign on an unprecedented level. When asked why Ireland was such a pivotal moment, Rodney Croome immediately says “Two reasons. One positive, one negative.”

The first is simple: there’s lots of people with Irish heritage in Australia. “Many Australians have a sense of attachment to Ireland,” Croome says. Less positive, though, was the sense of humiliation the successful referendum generated. “[There] was a sense of shame, that a small and traditionally very conservative and religious country had achieved marriage equality before we had.”

Perrett, an Irish Catholic himself, says Ireland was a stark wake-up call for Australians. “It wasn’t that long ago I was in Ireland, and before the news they stopped to say the rosary,” he says. “So for such a Catholic nation to make this change, it’s indicated that Australia was really dragging the chain.”

In the wake of Ireland, the lack of action on marriage equality rapidly moved from an easily-dismissed minority concern to a question of national identity. “There was a sense that our ostracism from the Anglosphere was complete,” says Croome. “And it doesn’t match the image that many Australians have of themselves and their country.”

“We pride ourselves on being tolerant, on our ethos of a fair go, on being inclusive. Not having marriage equality contradicts all of those Australian values. We also are very sensitive to how the rest of the world sees us, and increasingly we know that we are seen in a bad light because of this.”

Brazil legalised same-sex marriage in 2013.

The sense of urgency propelled by Ireland was quickly reflected in the Australian parliament. Advocates seized the moment, and a plethora of MPs previously opposed or ambivalent to marriage equality stepped up to declare their support. Feeling the momentum, opposition leader Bill Shorten introduced a marriage equality bill – which was completely ignored by the government, and promptly joined other private members bills already lying fallow.

Although derided by some as an opportunistic manoeuvre, Shorten’s gesture was significant: one, it was the first time a leader of a major party had sponsored legislation for marriage equality; and two, it forced Abbott’s hand.

Prior to the 2013 election, Abbott said marriage equality was a matter for the post-election Liberal partyroom. Despite being pressured on this commitment for months, Abbott has still not allowed a discussion on the issue within his party. However, after Shorten’s bill was introduced, Abbott’s language changed again. Any bill on marriage equality ought to be a cross-party effort that can be “owned by the whole parliament”, he said. His comments were interpreted as tacit approval for a non-partisan, cross-party bill to be brought forward.

Although Abbott’s goalpost-shifting has been met with frustration from advocates, it’s clear the pressure on him is growing. And the cross-party bill has forced his hand once again. However, there are two crucial caveats:

First, the government is able to block the bill from being voted on at all. As the bill is not government policy, whether it passes through for discussion and a vote is contingent on the House Selection Committee, which is dominated by MPs who are not in favour of the reform.

Second, even if the bill does come up for a debate, government policy remains in support of marriage as between a man and a woman. Government ministers, even if they disagree, are compelled to vote along the party line. Unless a conscience vote is granted, the cross-party bill will have no chance of passing.

Advocates are aware that politics could bring the bill down, but remain hopeful. “This bill has the best chance yet of prompting a debate on a free vote in the Liberal party room.” Croome says. And with a free vote, support will swell, he adds. “There are more politicians, particularly Liberals, who privately support the reform and are waiting for a free vote before they declare that.”

The pressure on Abbott and his party has manifested in the media, with conservative MPs leading an anti-marriage equality push in the days following the cross-party bill’s reveal. Several MPs lined up to express their disapproval, with reasons ranging from the rights of children, to the fact Australia’s Asian neighbours may see it as “decadent”, to the fear of polygamy.

While the cross-party effort is encouraging, the fight is far from over, seasoned campaigners warn. Numbers are too close to call, and Alex Greenwich and Rodney Croome say supporters across Australia still need to get in touch with their MPs and put across their points of view. “That is the key,” says Croome.

And in the parliament, it’s not the inner-city progressive MPs who will be the heroes of reform, says Greenwich. “It’s going to be the undecided MPs – people like John Alexander, people like Andrew Laming, people like Jason Wood, who find it in their hearts to take their part in history and be the votes that make this reform happen.”

Croome – who has spent years of his life patiently dismantling myths about same-sex couples – says there’s a silver lining to the fact Australia has fallen behind. “It’s that we can point to what a benefit marriage equality has been elsewhere, and how it hasn’t led to the end of the world,” he says. “The world is still there.”

Meanwhile, Shelton feels more and more beleaguered every year. A biased media won’t give him the time of day, he says. And the desires of gay couples are being prioritised over the rights of children. In Shelton’s worldview, social conservatives are David, while the LGBTI community looms as Goliath.

“This is an intolerant agenda that crushes little people who defend the state’s definition of marriage,” he says.

All the politicians interviewed by BuzzFeed News said marriage equality was inevitable, but neither Croome nor Shelton were that confident. The two leaders of their conflicting movements have too much at stake.

Shelton thinks the 2008 reforms that made same-sex de facto couples legally equal to opposite-sex couples could be the saving grace that makes marriage equality unnecessary. “There’s no discrimination in Australian law against same-sex couples, it’s all been removed,” he says. “There’s no equality issue.”

Unsurprisingly, Croome’s hesitation to adopt the word “inevitable” is for different reasons. “I would never say it’s inevitable, because I think that can engender a sense of complacency that it will happen of its own accord,” says Croome. “And it won’t.”

Croome and Shelton’s warring points of view could enter battle for the last time this year. If the last decade is anything to go by, public and parliamentary support for change will only continue to grow. The cross-party bill is set to be introduced on August 11, but whether it will emerge from parliamentary bureaucracy unscathed and ready to be voted on is anybody’s guess.

The Australian people have spoken – now the ball is in Tony Abbott’s court.

Warren Entsch, a Liberal MP who has been central to the creation of the cross-party bill, declined a request to be interviewed for this report.