When most 16-year-olds pick a restaurant, they might seize the opportunity to indulge a little bit: deep-fried, sugar-coated meals in busy high street venues. But Ashleigh Ponder chooses a Tesco café, a few minutes’ drive outside of Lincoln. The unremarkable café is half-full. The lunchtime rush is over, and the clientele is now mostly young families and elderly couples.

Ashleigh arrives with her mother, Gill, and picks a table in the corner of the cafe, walking with an air of self-assurance. “She’s a leader,” Gill says. “At school she always leads.”

Ashleigh, who is small for her age, is dressed casually, in a white blouse over a dark skirt. She says she loves going to the gym and cooking, and that she’s slowly teaching herself photography. She orders a glass of water.

“I only really started eating out again about three months ago,” she says, quietly scanning the menu.

Ashleigh is in recovery from anorexia; it’s been three years since she was first diagnosed. What sets Ashleigh’s story of recovery apart from her peers’, though, is how she’s been documenting her disorder – and now her recovery – on Instagram. She’s developed a fairly large following as a member of a huge online network of young people all affected by eating disorders.

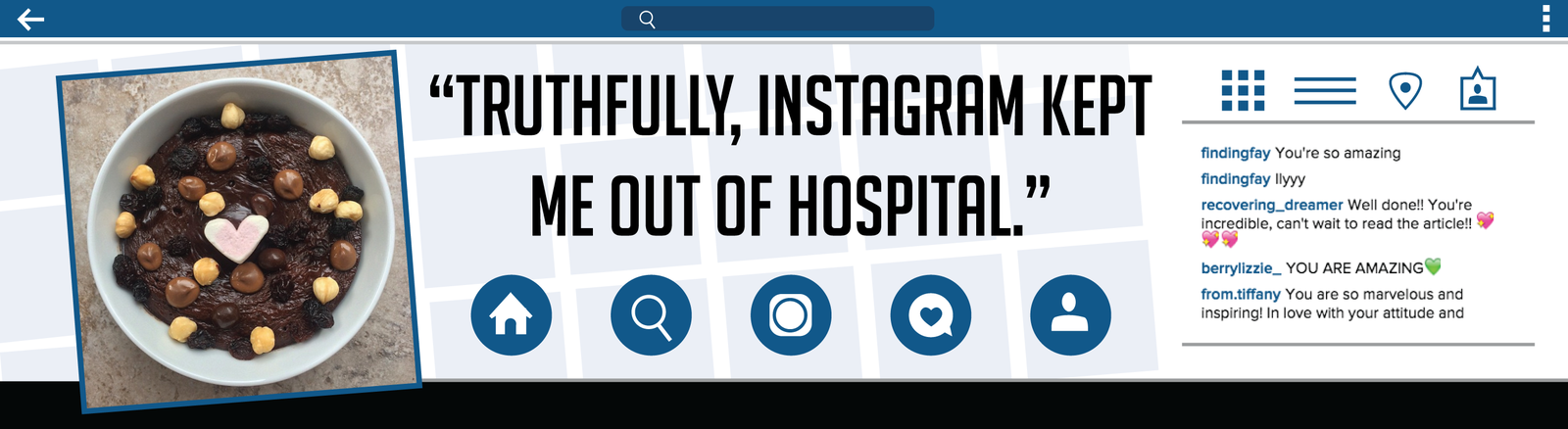

“Truthfully, Instagram kept me out of hospital,” she says.

Ashleigh was first diagnosed with anorexia when she was 13. She pinpoints her diagnosis with chronic fatigue syndrome as the beginning of her issues. It left her bedridden, unable to participate in her hobbies, and her weight dropped. A bad experience with a dietician worsened the problem.

“She was telling me to put double cream on everything and because I wasn’t doing anything active anymore, my weight ended up going towards the other end,” Ashleigh says. “I used to only eat things in a packet and only if they have the serving size on it.” She developed irrational fears about food: “I couldn’t eat an apple because I was scared one colour would have more calories than another.”

While in treatment, Ashleigh started searching for fellow frustrated anorexia patients on Instagram. She came across pro-ana content, but it never appealed to her. "I found those pro-ana sites sick because you could never wish someone to be as unhappy as it makes you,” she says.

More importantly, Ashleigh found a recovery community. She set up a new separate account and started to document her meals. Through Instagram’s search feature, hashtags, comments, and the followers she was gaining, Ashleigh found other young people in a similar situation to hers. She says they provided a vital support network.

“There’s a particular group of friends that I have now, that I spoke to on Instagram for two years. We talk really often; they’re my online best friends. I know two people on Instagram at the moment – one lives in the UK – and they’re going to California this summer to see their best friend, who they met through this.”

More than 725,000 people in the UK are currently affected by an eating disorder, according to an estimate in a study conducted in February. Girls in the UK between 15 and 19 are the most likely to develop one, with an estimated 4,610 new diagnoses each year. And with Instagram use in the last year doubling among 12-to-15-year-olds in the UK, it is unsurprising that teenagers suffering from eating disorders are finding kids with similar issues through the app.

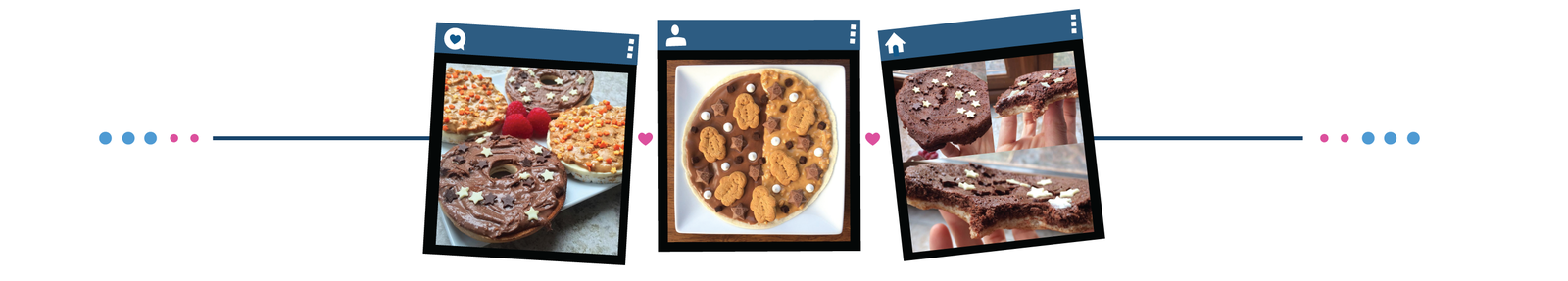

Members of Instagram’s recovery community primarily use their accounts to document their food consumption. The captions are sometimes descriptions of food, or just an anecdote from their day. Some users photograph huge piles of junk food, while other feeds focus on the quality of the photograph and the presentation of the food. Influential accounts within the community can grow to tens of thousands of followers. Ashleigh herself says, “I took a picture of everything I put in my mouth and made a collage at the end of each day to see what I had. I’d think, Wow, that’s not a lot at all."

Recoverers grow their followings and communicate using different hashtags. There’s #PlantBased for users following a diet largely made up of plants, #BeatAna for those in anorexia recovery, and #BalancedNotClean – which is also the name of Ashleigh’s account. Theirs is a subgroup that focuses on a varied diet and ignores "clean" eating trends. Ashleigh feels “clean eating” can aggravate already existing issues, even as she says she has respect for people following a vegan diet. “It’s not healthy to ban yourself from things – it’s like just another form of obsession about food.”

The discussion around eating disorders on social media platforms can be tricky, however. Instagram blocks certain hashtags associated with the promotion of eating disorders such as #Thinspo and #ProAna. Instagram told BuzzFeed News that tags like #Anorexia are allowed, though, because they facilitate a conversation about recovery. And any non-blocked tags associated with eating disorders come with a warning alert for triggering imagery. Despite these safeguards, variations of blocked hashtags are still viewable, and often suggested in Instagram’s search box when a user types in a banned phrase.

Ashleigh says that there are secret hashtags some members use to get around these restrictions, but she’s unaware of what they are.

Ashleigh’s family became aware of her account when she was repeatedly caught photographing meals. Although her mother admits that she is not a social media user, she takes an interest in her daughter’s account.

“We were so desperate for anything to help her that if she thought it was helping, then go with it,” says Gill. “Now we talk about it, how many followers she has, what she’s been posting.”

Many members of the Instagram recovery community do not reveal their identity, or have private accounts to prevent non-recovery members from accessing their photos. Ashleigh’s school friends came across her account early on without her knowledge. She compares the revealing of her identity to coming out. “My account was like a diary, I’d write, ‘Today so and so really annoyed me.’ Them seeing that was an invasion of privacy.”

Ashleigh is now fairly open with her account, posting photos of herself, and using her full name in places. “I used to be really shy," she says, "but talking to people online definitely made me more open.”

A year ago Ashleigh started a new Instagram account to mark the end of her “early recovery”. She also started a blog and is currently working with a variety of lifestyle companies through promoted posts. Similar to other food bloggers, Ashleigh participates in partnerships with brands whose products she advertises on her Instagram account.

Right now, she is working with Graze, a snack box company; San Clemente Cookie Dough, a dairy-, egg-, and gluten-free cookie company; The Protein Works, an online sports nutrition shop; Predator Nutrition, a bodybuilding supplement retailer; and Protein Pick And Mix, an online sports nutrition shop. Ashleigh says companies noticed her blog and Instagram and they slowly made connections with her.

“With Graze, I got a message on Tumblr asking if they could ask me some questions and it developed from there.”

Buzzfeed News contacted Ashleigh’s blog partners for more information. Graze and Predator Nutrition said that they were aware she was in recovery from an eating disorder, and that she receives a percentage of sales made through her website.

A representative from Graze stated via email: “We've been aware of Ashleigh's recovery blog for a while. She's been a loyal Graze customer for over two years and has featured our products with her own recipes for most of that time. Since we featured Ashleigh on our blog she has become a member of our affiliate program, where she receives £1.50 when one of her followers becomes a grazer.”

The other partners did not respond when contacted for comment.

Not everyone is as public about their recovery as Ashleigh is. Tiffany, who asked BuzzFeed News not to publish her last name, is a 22-year-old medical student from Scotland. She’s just returned to her studies after being diagnosed with anorexia two years ago. Tiffany discovered the Instagram recovery community while in hospital.

She says: “I saw how so many of these people were terrified, confused, and lost in their illness, and then I saw the incredible support they were all sharing. When you are recovering it is hard – it is painful, for me, knowing I helped one other person through their day, then that helped me to keep fighting too.”

Tiffany has received messages from others suffering from mental health issues. She says professional intervention was helpful for her and she would always encourage those contacting her to seek medical help. However, she reckons some girls may be using Instagram as a substitution for professional services, the availability of which can vary wildly between postcodes.

“Something that does concern me is sometimes people realise they are unwell and try to get help but because they are at a healthy weight or even overweight they can be disregarded by professionals. That can just reinforce the fear of asking for help.”

This concern about a lack of professional support is a feeling also expressed by Freya Smith, a 16-year-old from Cambridge. Freya had a bad relationship with food for a long time, and cites traumatic childhood experiences as a root cause of her disorder. Adolescent trauma is a common cause for eating disorders; the National Eating Disorder Association refers to research that suggests 30% of eating disorder patients have been sexually abused.

“Sometimes people don't get the support they need from mental health services because they just don't understand,” she says. “But here [on Instagram] everyone supports everyone with their recovery no matter who they are or where they come from.”

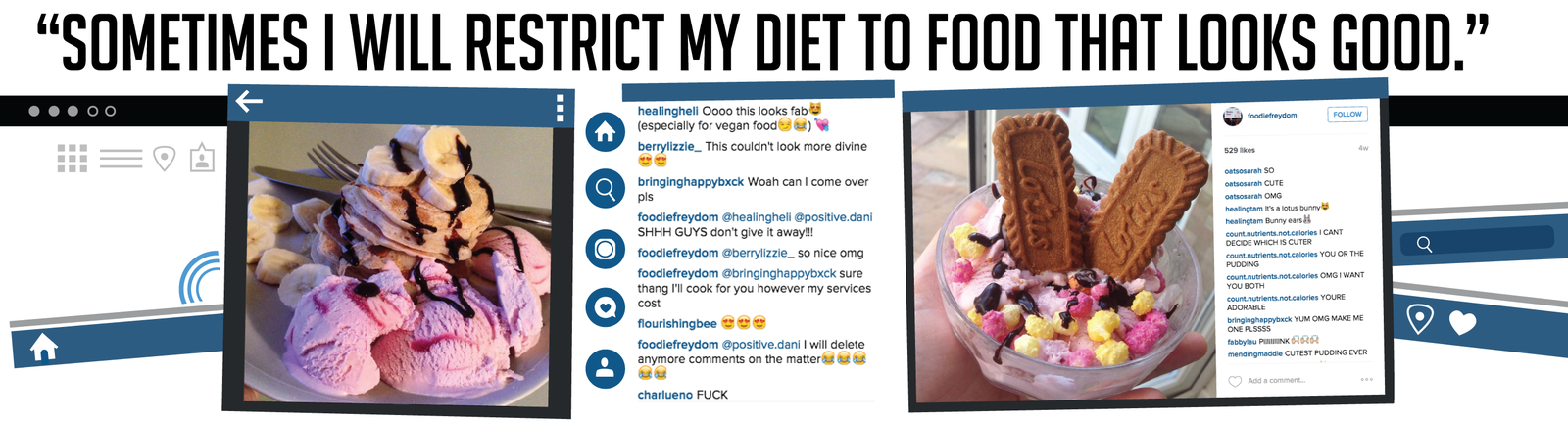

Freya created her account when she was first discharged from treatment for anorexia. She says it became more important when she relapsed and wanted to find others in her situation. Unlike Ashleigh or Tiffany, however, Freya places importance on the aesthetic quality of her photos. Her account is full of photos of sweets spilling out of their cases, rows and rows of cereal bars, chocolate bars perfectly piled on top of each other. It often affects how she eats, she says, but she tries not to be affected by the community’s many subgroups.

“I do only post food that looks good, so sometimes I will restrict my diet to food that looks good. I also feel a lot of pressure to eat unhealthy food.”

Deanne Jade, the founder of the UK-based National Centre for Eating Disorders, is worried about the lack of professional leadership on Instagram. She claims she has seen similar Facebook pages on which young people encourage one another away from professional care. She believes these communities may fuel the unofficial disorder of “orthorexia”, an obsession with the quality of food someone consumes.

BuzzFeed News reached out to Jade to ask why the centre still lacked a social media presence in light of evidence showing the large number of young people on Instagram. Jade was away on holiday so unable to comment.

There are some professionals who believe that positive dialogue between eating disorder sufferers could be beneficial. “It seems like a positive idea: young people in a similar situation, supporting one another," adolescent psychiatrist Dr Tony Jaffa told BuzzFeed News. He admitted that although he has not come across these groups himself, he is welcoming of the idea.

This sentiment is shared by media psychologist Dr Pamela Rutledge. She advocates for support groups as a form of social connection and acceptance for those who feel their disorder has seen them ostracised. The plus of the Instagram community, she says, is that it is always available for the girls to access, unlike professional care. The element of visual evidence of recovery can be especially helpful and, unlike Jade, Rutledge believes that the images seen on recovery pages aren’t necessarily triggering, but a way for sufferers to retrain their negative responses, such as a fear of junk food.

“These girls are creating a narrative – their story – in powerful ways and the community members are able to identity and project themselves into the journeys, which increases the probability that they will model the recovery behaviours.”

That narrative-building Rutledge likes about Instagram is instantly noticeable when the Tesco cafe’s server brings Ashleigh’s lunch to the table. She immediately posts a picture of it on her Instagram account.

“Gammon, chicken, veg, and potatoes – which again shows I've come a long way as a result of this community. This stuff is all unknown calorie and portioned out by me, where at one point I couldn't eat anything unless it was in a specifically portioned packet with the nutrition info on... Now this doesn't even phase [sic] me,” she captions the photo.

Within moments the post is littered with comments and likes, telling Ashleigh how inspiring she is. It currently has over 500 likes. Ashleigh says that while not true now, when she first started her account getting feedback from her followers was essential. “Back then I wouldn’t eat it if I couldn’t take a picture of it, because I so desperately wanted to prove that I was having these things. Now I’d rather take a photo than worry about the presentation.”

“Well done!! You're incredible,” user recovering_dreamer comments.

“You are so marvelous and inspiring! In love with your attitude and account. Stay amazing,” another user, from.tiffany, comments.

“My account has become more than recovery, it allowed me to become me," Ashleigh says. “It’s built my confidence. I’m just so glad I got through it and wish everyone can."