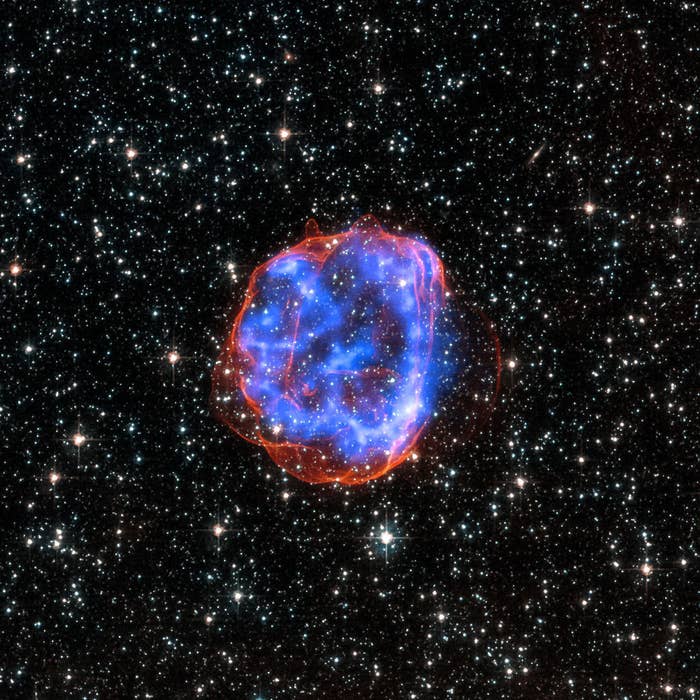

Scientists have found evidence of a whole bunch of supernovae – when stars explode at the end of their life – that happened in our cosmic neighbourhood around 2 million years ago.

Supernova happen at the end of a star's life when it's run out of hydrogen and helium to fuse for energy. Elements that have been fused in the star during this death are flung out across space.

But the researchers didn't discover these nearby and most recent supernovae by looking to the night sky.

They found iron-60, a radioactive element only created when stars die, in samples from the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans. Iron-60 was found in the ocean crust for the first time over a decade ago, but at the time scientists couldn't say for sure where it came from.

Now, because they've discovered it all across the globe, they think exploding stars are the most likely culprits.

By looking in detail at ocean sediments, the scientists worked out that a series of supernovae close to Earth happened between 3.2 and 1.7 million years ago. Two papers on the finding are published today in the journal Nature.

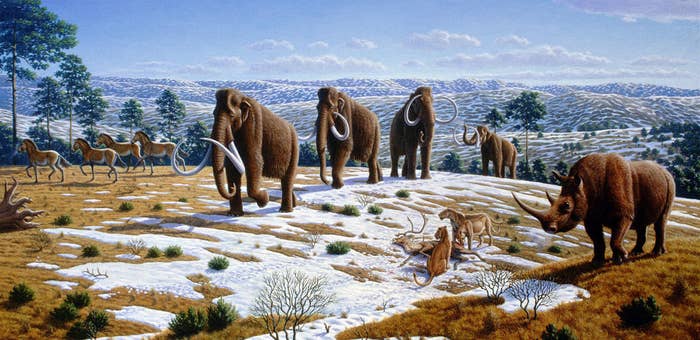

This time period, weirdly, coincides with a time in Earth's history when the temperature got cooler.

During the time period in which the supernova are believed to have happened, Earth got cooler and we transitioned into the Pleistocene era, which lasted from about 2.6 million to 12,000 years ago.

"We do not know if there is a link between supernova activity and colder temperature," astrophysicist Adrian Melott wrote in a commentary accompanying the two scientific papers, also published in Nature.

All supernovae identified were beyond the "kill distance" – a 30-light-year radius around our solar system inside which, if a supernova were to explode, the effects to life on Earth would be "catastrophic" – says Melott.

The two closest supernovae happened at distances around 300 light years from Earth.

These two contributed the most to the iron-60 found on Earth now, although there were other supernovae that played a small part.

"A few per cent of fresh [iron-60] was captured in dust and deposited on Earth" during this time, the authors of one paper published today write.

The supernovae would have been bright enough to see from Earth during the day.

The stars are believed to have belonged to a group of stars which exploded at various times, forming the "Local Bubble" of hot plasma, in which our solar system is embedded.

Though the supernovae are now long gone, by looking at the ones that are still left and working backwards, the team were able to model exactly when and where they think the stars that deposited iron-60 on Earth underwent their spectacular deaths.