My hands grip the aging staircase railing as I ascend a series of steps suspended roughly 70 feet in the air. Below me, the floor is a scattered mosaic of broken plastic and rubble. I’ve wedged a pair of squishy foam plugs into my ears, offering a comfortable barrier between myself and a chorus of whirring machines producing a dull white hum. The air is thick and dank, and every few minutes I’m startled by a distant crashing sound. All around me, there is trash.

You see, I’m what one might (and should) deem a “casual recycler” — I care about the Earth (don’t get it twisted!), but when it comes to properly discarding my trash, more times than not I’ve opted to do what was most convenient for me in the moment. I have a recycling bin at my apartment, but I don’t always know if what I’m putting in there is definitively recyclable (I’m looking at you, empty toothpaste tubes), and my apartment complex doesn’t have separate bins for paper and plastics. So when I was given the opportunity, while working with Ad Council and Keep America Beautiful, to visit the Sims Recycling Plant (the nation’s largest) in Brooklyn, New York, I welcomed it with open, impressionable arms.

Before venturing to the recycling plant, it felt essential to carry out some recycling recon in order to understand how those around me were handling their trash. My friends offered some insightful queries: It turns out the most puzzling “Can I recycle this?!” items included peanut butter jars, those pesky toothpaste tubes, cosmetics containers, and any recyclable container with food in it.

When I arrive at the plant, I’m greeted by Sims’ outreach and education manager, Sam Silver. He’s not dressed in a lab coat, but he might as well be; just a couple minutes after our introduction, Silver is already laying down facts as if it were a science, cluing me in on a day in the life at a materials recovery facility as well as dispelling some oft-perplexing recycling myths. “Peanut butter jars are fine,” he tells me before I can even ask. I breathe a sigh of relief as he elaborates: “Glass peanut butter jars get broken up and sorted here, though any cleaning and/or melting happens at other glass recycling facilities.” I fight the urge to drop a message into the group chat.

Within the first 15 minutes of us knowing each other, Silver has exposed me to more recycling know-how than I’d ever been privy to in my life. "Aluminum can be twice as valuable as most plastic recyclables,” he says, “but it’s the least recycled recyclable material.” He explains that plastics are sorted by their “resin type,” which refers to their thickness and the ease with which they may be broken down. Not so intimidating, I think.

That is, until we make our way into the plant.

Clad in steel-toed boots and hard hats, Silver, my colleagues, and I make our way toward the plant's expansive warehouse. When we arrive, we're greeted by humbling towers of garbage perched in a wide, open space. Seeing 50-foot towers of trash taller than my house is as jarring as you might imagine.

Silver provides some insight into the vista of recyclables before us: “We get about 90 trucks bringing in recyclable material a day.” My be-goggled eyes betray any semblance of nonchalance. Ninety trucks? A day?! Then I’m told that most of the material before me actually comes from barges that traverse the surrounding rivers, delivering unknown mounds of material to New York City. “That’s 800 tons actively being sorted a day...” Silver pauses, then: “...for a staff of roughly 86 people.” In this moment, I quietly, solemnly swear never to complain about taking out the trash ever again.

“There’s more science involved at these plants than one might imagine," Silver says. Infrared optical sorters attached to the raucous machines surrounding us use actual lasers to identify the different types of plastics passing through them. When these sorters determine which kinds are approaching, they trigger an air jet that then propels the item off-course and onto the proper trajectory. Every one of these sorters is looking for a different item or type of plastic — clear or colored, plastics of varying resin numbers. All of this sorting and air-shooting can happen about 10,000 times per minute.

What all these machines and sorters and belts are working toward is the production of many, many bales of recycled materials, all broken down and sorted by category. Once enough of one type of material is received, they’re hydraulically compressed into a bale then sent off and shipped out to market. When this is first explained to me, I have a truly impossible time curating an image in my mind. For the most part, my understanding of “hydraulics” is limited to an episode of Pimp My Ride I once saw at my cousin’s house during a family gathering in 2005.

Instead, what I see as we cautiously tread between these machines is the sum of a system that’s actively operating to make our Earth more sustainable. Every which way, there’s a conveyor belt moving with furious determination, a neighborly plant employee sorting through materials, and, more than once, a bowling ball.

It is suspended within this industrial jungle gym that I finally begin to understand the scope of my current situation. This warehouse room is big, yes, but not so big that I’m not entirely floored at the fact that, theoretically, every bit of every recycling New Yorker’s produce ends up here, where the reclaiming artistes of Sims Recycling Plant handle it. That all I have to do is place my recycling in the proper bin, and they’ll take it from there — that’s actually amazing. And simple. The only onus that falls on me — or rather, us — is so extremely doable. In this moment, I feel small and appreciative, repentant for the times I’ve thrown peanut-butter-and-jelly-flecked aluminum foil directly into the trash with frivolous abandon.

Post-epiphany, we’re back on solid ground, finding our bearings in a labyrinth of varied recyclable bales; there are large rectangular cubes of aluminum speckled with brilliant hues of grape-soda purple and cola-can red. There are massive collections of squished-together water bottles and tons and tons of collected milk jugs. Knowing these bales are all going to be shipped off and given a second life hits me hard; Silver tells me that 11,000 of these bales are made here every month.

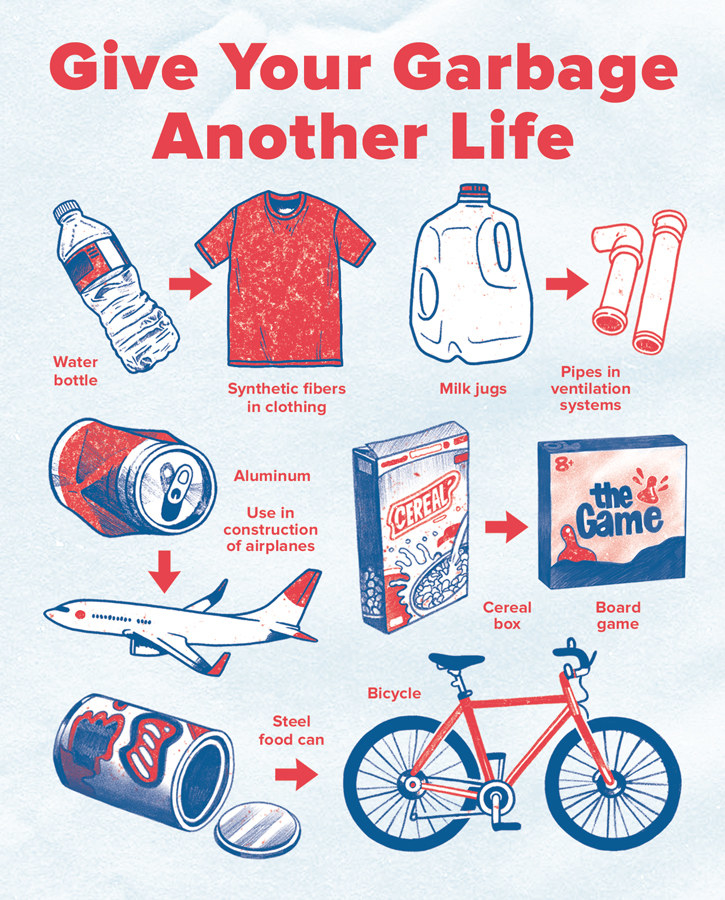

When we’ve de-goggled and squeezed off the last of our steel-toed boots, I find a room with Silver and ask him to tell me everything he wants novices like me to know about recycling. He lays it out clear: “While some water bottles just become water bottles again, there’s also potential for them to find a second life in synthetic fibres, used to create things like carpets, clothing, and insulation. Clear milk jugs are becoming pipes inside buildings and ventilation systems and can be used in the production of bins and outdoor furniture.” During most of this, I am adding what I assume is constructive commentary, gasping and repetitively saying such profound things like “Whoa!” and “What?!” Pulling me from my stupor, Silver reminds me that the end goal is to have these recycled materials be repurposed into something more durable that then might help extend that material’s reincarnation even further.

What comes next is equal parts admonition and plea: “The recycling industry is really one of the most dangerous industries in the US,” he says, “because of the moving parts, because of all the equipment, because of contact with a whole wide variety of things.” And because of dangerous materials being inaccurately discarded. Laptop batteries and even AA or AAA batteries are not only incapable of being recycled at these recovery facilities but also pose a very real threat to the work environment. Instead, it’s best to bring your rechargeable batteries to any retailer that sells them, as they’re required by law to accept used batteries. “Laptop batteries can explode,” Sam warns. “The other week, we had firecrackers in here. A lot of people don’t realize the amount of labor and people-power that goes into recycling their stuff. It’s not all machines.” I nod gravely, equipped with a new understanding of my behind-the-scenes experience.

Analogous to batteries, there are a few specific materials that simply cannot be accepted by recycling plants. Empty toothpaste tubes, I learn, are best saved for mail-in programs and certain drop-off locations, often offered by oral care manufacturers. Beauty products that you’re totally over can be cleaned and brought to retailers, and larger-scale grocery chains are required by law to have a designated space for deposit.

Before leaving the plant, I thank Silver for all he’s offered my colleagues and me today. He’s kind and cordial and absolutely casual — every bit of information that blew my mind this morning came second nature to him. I’ve realized today the importance of being curious, of asking questions in the face of uncertainty — if you don’t know what to recycle, find out; if you want to understand how your world works, wiggle your way behind the curtain. When you do, you might realize just how much change you can effect through your own small changes.

All photos by Sarah Stone; design by Kevin Valente / © BuzzFeed