Jessie Craigen was a mess. She struggled to support herself financially, inspired snickering comments about her appearance and nursed an embarrassingly unrequited love for another woman. She was vocal in her passions, unrelenting in her judgment and fierce in her loyalty. Today, she’s lucky if she’s mentioned in a footnote about working-class women in the British suffrage movement.

To me, she’s a hero.

I first encountered Jessie while researching 19th century feminist activism. She was an anomaly in her suffragist activist circles: poor, unladylike and too honest for her own good.

People who don’t fit a certain mold rarely make history books, no matter how much heavy lifting they do. Jessie’s life never fit an easy narrative of progress. Her frustrations and flaws are present in every one of her successes and failures. Ultimately, she sacrificed everything, including her chance to be remembered and celebrated, to speak out on her own terms.

Jessie Craigen was born in 1834 or 1835, most likely in London. Her father was a sea captain and her mother, an actress, raised Jessie alone. Jessie herself first appeared on stage at age four. However, she was too passionate about political and religious topics to stick to acting out others’ plays.

The first record of Jessie’s career as a traveling temperance speaker, lecturing on the dangers of alcohol, appears when Jessie was 25, in The Preston Guardian. Today, prohibition of alcohol seems prudish and ultimately pointless. For Jessie, it was a revolutionary way to draw attention to the hypocrisies of men and the wealthy, whose abuse of alcohol disproportionately affected women, especially working-class women.

In the beginning of her career, if Jessie wanted to attract an audience, she’d hire a local bell-ringer. Then, as the clanging bell attracted a crowd, she would stand on a table, chair or barrel and say what she needed to say.

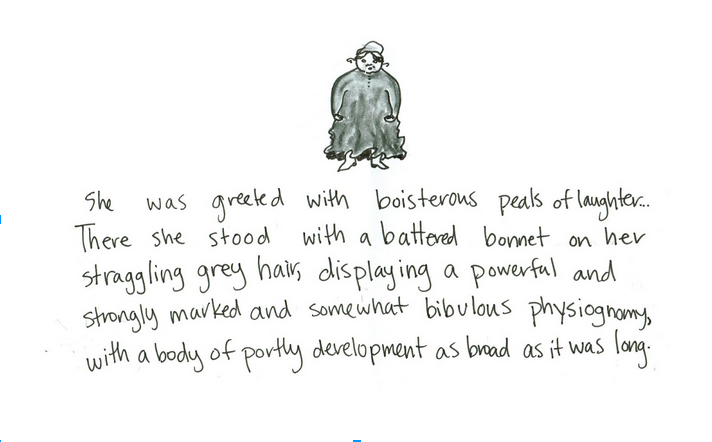

Descriptions of Jessie don’t mince words: she was, quite bluntly, ugly. She was short and stout. Her clothing was out-of-style and tattered. Her voice was deep and masculine. Often, Jessie’s audience was laughing at her before she started speaking. Yet, she would win them over.

“In two minutes the whole audience was listening intently; within five she had them in fits of laughter, this time not at her but with her,” reads an account of one of her speeches. Her acting background gave Jessie a theatrical flair, with her audiences falling into call-and-response and bursting into cheers and sobs.

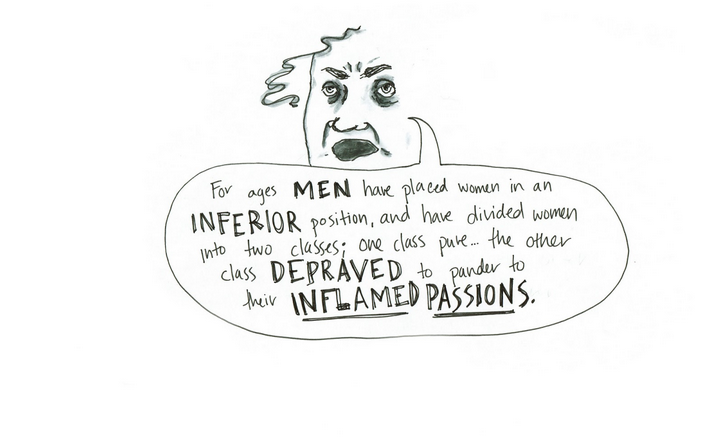

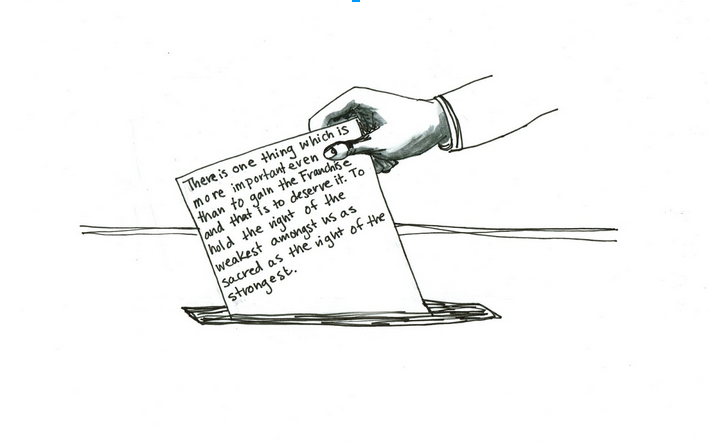

As her renown grew, Jessie expanded her subject matter beyond temperance. By the late 1870s, she had become involved in the women’s suffrage movement, where she met some of her closest friends and supporters: radical middle-class women like the Quaker Priestman sisters. Soon after, she became a vocal opponent of the Contagious Diseases Acts, which gave police permission to invasively “inspect” and imprison suspected sex workers in naval port cities. Jessie spoke out against anything she saw as an affront to personal liberty, fighting for animal rights, trade unions and universal suffrage for men as well as women. She even opposed mandatory vaccination.

Jessie became known by her mostly middle-class collaborators and employers for her ability to reach working-class crowds in a way others could not. When she spoke about women’s suffrage, she could win over male miners and factory workers who, for the most part, couldn’t yet vote themselves. Constantly traveling, Jessie would send petitions back to organization leadership, grubby from being passed around and signed by dozens convinced by her arguments in open air meetings.

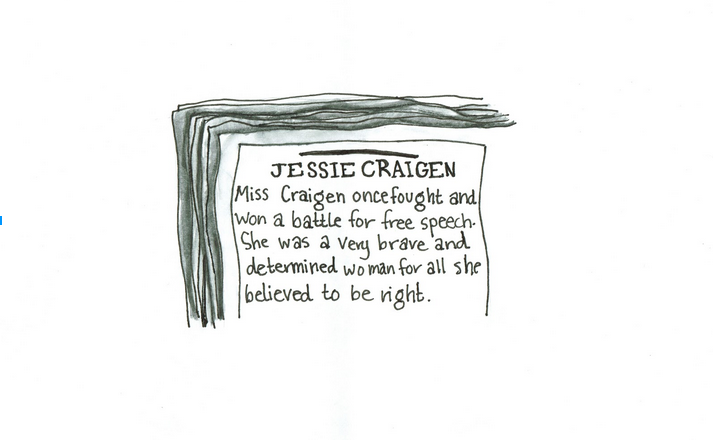

Of course, not everyone agreed. More than once, angry members of the audience attacked Jessie. She became one of the first advocates for women’s suffrage – if not the first – to be arrested for publicly speaking out for the cause. None of this made her back down.

In her personal life, Jessie was equally passionate and, at times, reckless. Jessie was unmarried and known for her romantic friendships with other women. The most intense of these relationships was with Helen Taylor, a well-known activist dedicated to women’s and Irish rights who worked closely with her famous stepfather, John Stuart Mill.

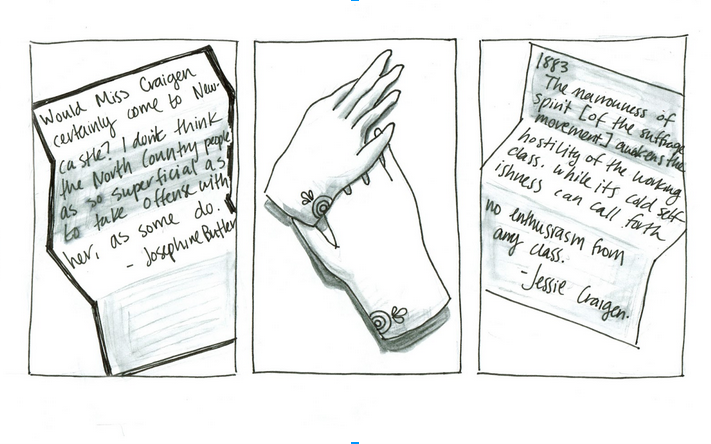

In the early 1880s, Jessie “anchored her very heart” to Helen, according to her close friend Anna Maria Priestman. As romantic friendships between women were common at the time, Jessie’s extreme dedication to Helen was accepted in the duo’s overlapping activist circles. However, friends were concerned that the sensitive Jessie was more invested in the relationship than Helen, hinting that Helen may have been more interested in Jessie’s power as a speaker than her personality. The friends were right to worry.

“I love you more than life,” Jessie wrote Helen in 1883, about a year after the pair stopped speaking due to Jessie’s vocal distaste for one of Helen’s fellow Irish rights activists. “I want nothing of you except that you will let me be a comfort to you as you used to tell me once that I was.”

After their disagreement, Helen refused to read Jessie’s letters, throwing Jessie into a depression. Jessie wrote on, convincing mutual friends to deliver the adoring notes. Prior to their disagreement, Jessie had traveled to Ireland at Helen’s request to speak on Irish land rights, a cause that divided suffragists. Helen changed her plans last minute, forcing Jessie to unhappily travel as the sole woman in a party of men. Still, Jessie remained dedicated, attempting to quit her paid speaking gigs even when Helen wouldn’t return her letters to support her political career in Ireland.

Mutual friends convinced Jessie to return to her paid jobs for organizations dedicated to women’s suffrage and repealing the Contagious Diseases Acts. At this point, Jessie was speaking at national meetings and had become an extremely popular traveling speaker. Other women at similar levels of renown went on to assume leadership positions and published books. A number have since gone down in history as the foremothers of the modern feminist movement.

Instead of allowing her a stable platform, Jessie’s prominence highlighted how her “unladylike” nature separated her from fellow activists. She was encouraged to change aspects of her identity to fit a certain feminine ideal, even as she attempted to change laws that restricted herself and others.

Jessie, the token working-class woman, regularly found herself on stage next to polished female middle-class speakers. Having never abandoned the forceful and theatrical manner of speaking that launched her to popularity, she did not fit in, in mannerisms or appearance. In an effort to help Jessie appeal to her growing middle-class audience, some wealthy suffragists decided to give her a makeover. In the 1880s, this meant “silk dresses and lavender kid gloves.”

Jessie’s “masculine” appearance gave critics evidence of what women would become if they gained the right to vote: unladylike, messy, unrestrained.

The new look didn’t stick. According to the Priestman sisters, the moderate activists who pushed for the makeover failed to understand that Jessie’s unfiltered manner was what had made her successful. Going forward, they helped outfit Jessie in plainly-made clothing, aiming for “inconspicuous” instead of fashionable. Still, Jessie’s “masculine” appearance gave critics evidence of what women would become if they gained the right to vote: unladylike, messy, unrestrained.

Failing to change Jessie’s image, organizers limited her audiences. Middle-class activists who could afford to work for free were seen as speaking out of pure moral conviction, while critics condemned Jessie as a hired shrill. Leadership of the movement to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts restricted Jessie and other paid agents to public meetings, while ministers and “educated ladies” were encouraged to expand their work to private, more intimate venues.

Jessie founded her career on her desire to speak freely and to fight for the ability to do so. However, as she was paid for these speeches, tensions grew between Jessie and her employers in regards to subject matter. Jessie liked to give multiple speeches on different subjects at each location she visited. She also would sometimes combine several topics into one speech. A talk on how the Contagious Diseases Acts manipulated poor women to suit male interests could morph into a rousing speech on the need for women’s suffrage. While Jessie saw these topics as inherently interrelated, employers became reticent to hire a distinctive speaker who would espouse sometimes controversial viewpoints.

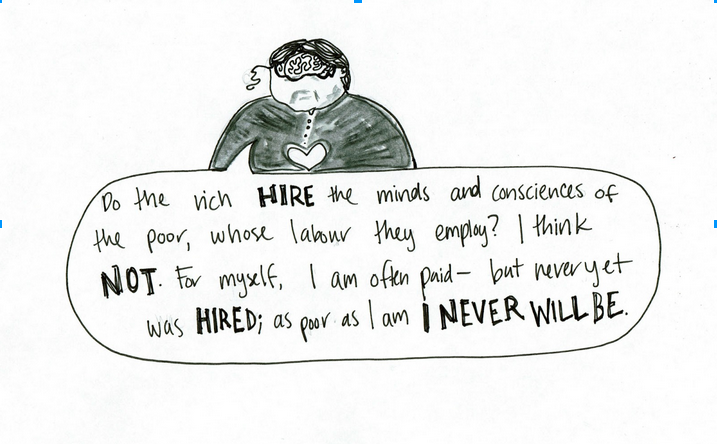

At this time, Jessie’s dedication to Irish land rights became a major disagreement between herself and her employers. While Jessie became a vocal advocate for Irish land rights due in part to Helen Taylor’s influence, moderate suffrage leadership saw the issue as distracting. In one argument, a suffragist leader criticized Jessie for speaking about Irish independence during a trip paid for by a woman’s suffrage organization. Outraged, Jessie penned and published an open letter to her employers, venting her frustration as one of the few working-class women in the organization:

Jessie’s determination to speak her mind hindered her ability play politics or censor herself. Even in casual conversations, Jessie could be a difficult person to talk to, launching into hysterical monologues about political and personal issues. Professionally, this quality became more damning. In an 1883 national suffragist meeting, Jessie broke protocol to demand the explicit inclusion of married women’s right to vote, complicating her future ability to find ongoing work.

In 1884, the Contagious Diseases Acts were repealed and the Reform Acts for women’s suffrage failed to pass. Jessie went from an in-demand speaker to an unemployable radical, with one major employer no longer relevant and the other splintering following its defeat. Even temperance speaking gigs dried up, with leadership blaming her lack of success on the fact she wasn’t “ladylike.”

Jessie became unable to pay for accommodations when traveling for lectures, and fell into debt. She continued to try and support Helen Taylor’s political career, publishing a pamphlet with her quickly evaporating money in 1885 that called Helen the "greatest friend the working classes ever had.” Helen never responded. The Priestman sisters started a fund to help support Jessie, but money ran out in the late 1880s. Her reputation as erratic and unreliable grew. Soon, her former fellow activists and friends stopped responding to her letters.

It’s easy to paint these friends as villains, but reading their letters from the 1880s, it is clear they cared about Jessie. They were alternately annoyed by and concerned for their brilliant but obstinate friend. They raised money for her, bought her clothing and supported her career, but could not understand her loud, unrefined stubbornness. Why couldn’t she compromise, or at least compose herself?

Most women today like to imagine they would have been marching for women’s suffrage if born 200 years earlier, but the reality isn’t as clear cut. Jessie saw everything from suffrage to mandatory vaccination as a battle between absolute right and wrong. Few people alive today would agree with all of her opinions or her reasons to support causes now seen as progressive. However, her efforts, along with many others’ forgotten throughout history, helped shape the world we now live in.

"Her efforts, along with many others’ forgotten throughout history, helped shape the world we now live in."

To help enact these changes, Jessie had to suffer thousands of everyday indignities. She wanted to be accepted, if not by a hypocritical society she rallied against, then by her friends, fellow activists and the woman she loved. Homophobia as we would understand it today didn’t lead to Jessie’s fall from prominence. Her relationship with Helen hurt her, but in the way loving anyone can lead to poor decisions when things fall apart. Jessie's so-called masculinity, however, certainly contributed. While prominent women in romantic friendships often fit certain Victorian norms, Jessie’s love for Helen and lack of a husband or children underscored what others saw as her unfeminine and even unnatural character.

Ultimately, injustice and the crawling pace of progress infuriated Jessie, as did her peers’ willingness to accept half-measures and compromises. Jessie became a renowned speaker because she didn’t censor herself for anyone, even people she respected. She was ostracized and erased from history for the same reasons.

Jessie Craigen died in 1899 at age 64, alone and essentially broke. She was living in Bristol, where she had moved after falling into debt and losing touch with most of her friends. Though she no longer traveled, she continued to speak publicly, mostly about animal rights, to local audiences. When she died, she left no money — just her furniture, her clothing and her books. Her obituary read:

All quotes in illustrations are from Jessie or her contemporaries. If you want to read more of Jessie Craigen’s writing and letters, check out The Women’s Library in London for letters and reports regarding the Contagious Diseases Acts in the Josephine Butler Collection. The London School of Economics has letters from and about Jessie in The Mill-Taylor Collection (named after Helen Mill Taylor!). If you have to pick just one thing to read about Jessie, I recommend Sandra Stanley Holton’s “Silk Dresses and Lavender Kid Gloves: The Wayward Career of Jessie Craigen, Working Suffragist.”