The documentary Nothing Left Unsaid: Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper takes its audience through Vanderbilt's 90-plus-year life, which includes the vicious custody fight over her when she was a child in 1934 (called the "trial of the century" before the O.J. Simpson trial stole that moniker); the tragic deaths that have punctuated her personal history; her fraught relationship with the Vanderbilt family; and her many romances and marriages.

Liz Garbus directed the documentary, which premieres on HBO on April 9, but it's Anderson Cooper, Vanderbilt's son, who is the on-camera interviewer. He employs his journalistic skills as his mother's loving inquisitor, prodding her about things he has never known, plus her most difficult-to-discuss subjects.

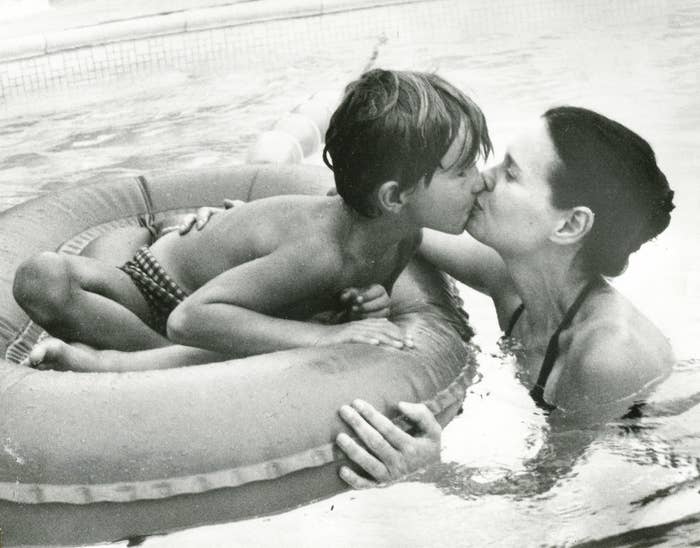

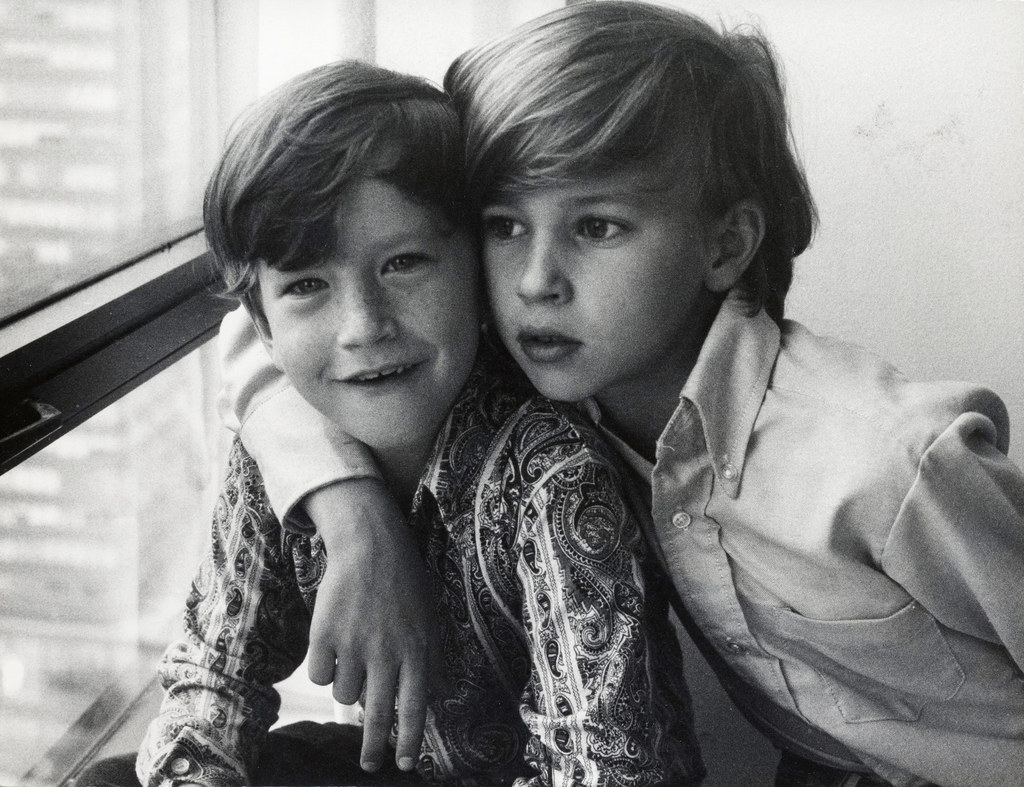

Living longer than 90 years insures a fair portion of woes, but Vanderbilt has endured more than her share — her father died before she could form memories of him, and another of her sons, Carter Cooper, committed suicide in 1988 when he was 23. Nothing Left Unsaid is certainly a crier. But it also imparts an equal measure of joy and laughter. (Vanderbilt and Cooper's conversation continued after the filming stopped, which has turned into a newly released book, The Rainbow Comes and Goes: A Mother and Son on Life, Love, and Loss.)

Nothing Left Unsaid premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January, and BuzzFeed News sat down with Cooper there, in Park City, Utah, to discuss his mother's life, and the making of the film. He also turned on his own recorder during the interview — "It's just a habit!" he said.

1. The title of the documentary was emphatically chosen.

The phrase "nothing left unsaid" is the articulation of an idea: Parents won't always be around to tell their stories — which Cooper knows well, since his father died when he was 10. So with his mother, Cooper pressed her to tell him all the things he might not know otherwise: about her life, their family, his late father, and on difficult topics such as his brother's suicide. The aim, he said, is to avoid regrets that "something was left unsaid."

To discuss such things required a new language between them. "Our relationship changes with our parents as they age and as we age," Cooper said. "But oftentimes we don't think of new ways to talk to them, new ways to relate to them. And we get stuck in the past awkwardness, or the past anger."

"I think there's something very freeing about shedding that old skin," he continued. "And asking those questions, and developing a new way of conversing with your parent or loved one."

2. The documentary and the book are culminations of Cooper's "nothing left unsaid" philosophy. But he started the process long before.

When Cooper was a teenager, he began videotaping Vanderbilt: "Not even asking her questions, but just videotaping," he said. Some of the footage has ended up in the documentary, including an immediately emotional opening scene on the beach, when the audience sees a young Cooper instructing his mother on how to hold the camera. "I didn't remember shooting that stuff," Cooper said.

It was during another home-video session, also featured in the movie, that Vanderbilt told Cooper, then in his early twenties, that "it's only once you accept that life is a tragedy that you can start to live." And, he said, how she envisions herself as "in her core having a rock-hard diamond that nothing can get at, and nothing can scratch."

3. Cooper thought of directing the documentary himself: "Maybe it's a film I'll shoot on my iPhone, and just have it be a very personal thing."

But then he realized that would not work — that he would end up repeating the mythologies he already had in his head about his mother and their family. He needed, he said, a "real filmmaker to look at this, because I think her story is far more interesting than even I realize."

He approached Sheila Nevins, the president of HBO Documentary Films, with the idea that cable network should do a documentary about his mother; Nevins suggested Garbus, now a two-time Oscar nominee (for 1998's The Farm: Angola, USA and 2015's What Happened, Miss Simone?), who has directed a number of documentaries for HBO (including Love, Marilyn and Bobby Fischer Against the World). After Cooper watched her work, he agreed that Garbus was the best choice.

And, though Cooper is an executive producer on the movie, he wants to be clear: "Liz had full creative control," he said. "I didn't want this to be — nor did my mom, to her credit — like an A&E special or a sugarcoated thing. It's not a vanity project. I wanted a film that could stand alone, and that would stand the test of time."

It was Garbus's idea, Cooper said, that he be the one to interview Vanderbilt on camera. As a result, the film, as much as it is a biography of Vanderbilt, is also a deeply personal portrait of a parent and her adult son — which was a surprise to Cooper. "I didn't realize when we were shooting the documentary that I was going to be in it to the extent that I was," he said. "That was all up to Liz to decide. I really thought it was more my mom's story."

But he certainly saw the advantage in Garbus' idea, in terms of producing something new about Vanderbilt, who has been in the public eye for so much of her life. Cooper said, "I know my mom so well that I know when she's giving a pat answer to something that she's given before, so I can easily say to her what nobody else can say to her: 'I know that story, you've told it a million times, what's the real deal?'"

4. One thing Cooper never tires of, even if she has told the stories before, is hearing about her adventurous, extensive romantic life. Her conquests included Errol Flynn, Marlon Brando, and Frank Sinatra.

In the film, Cooper clearly revels in stories about his mother's sexual past. And during the Q&A after the doc's Sundance premiere, he delightedly told a story about how his mother at age 85 described a man she was dating as "the Nijinsky of cunnilingus."

When reminded of his remarks at the festival, which had earned a big audience reaction, Cooper laughed: "I just find it amazing!"

Did he remember when he began to realize that his mother had, as he put it, "hooked up a lot?"

"We would watch old movies, and I would say, 'Did you ever know Errol Flynn?'" Cooper said. "And she would be, like..." he imitated his mother's patrician accent, "'...Oh, yes.'"

"As a teenager, no one really wants to think about their mom's sex life," he said. "But certainly as an adult, my mom started telling me more stories. And through this, in the film and the book, a lot more came out."

5. Despite the imperative to discuss their feelings openly during the documentary, Cooper did not broach his coming out until they wrote the book.

Cooper told Vanderbilt he was gay when he was 22. The conversation was, he said, something they had "never even discussed." Cooper realized later that his nervousness about coming out to her, and his mother's subsequent reaction, were informed by the fact that Vanderbilt's mother had been called a lesbian during the custody fight — a confusing, terrifying thing for young Gloria, and a criminal act to most of the world in the 1930s. (Vanderbilt writes in The Rainbow Comes and Goes that her mother had relationships with both men and women.)

"She was totally cool with it," Cooper said of Vanderbilt's reaction to his announcement. "But there were just a couple of things she said which surprised me. One of the things she said was, 'Don't make any definite decisions.' Which was partly based on how I phrased what I said to her. But it was just interesting to me. I realized it brought up all sorts of things from the fact that her mother was a lesbian."

6. Cooper's father, Wyatt Cooper, was an open person, and Anderson felt he knew all about his dad's life and family. He felt the opposite way about the Vanderbilts.

While his father had told him about his upbringing in Mississippi, and had photographs of his childhood and past, "My mom had none of that, and never talked about it," he said. That the Vanderbilts were of significance to New York and American history proved to be even more confusing. "My dad took me to see a statue of Cornelius Vanderbilt at Grand Central Station. I thought all grandparents turned into statues when they died because of this." It wasn't until he was a teenager, he said, that he began to read about that side of his family in history books.

7. Throughout this whole process, it was his mother's emotional journey — more than stories about the Vanderbilts — that has interested him the most.

Cooper knew there was a sadness to his mother, but hadn't before realized some of its roots: deep regret. "It wasn't until the making of this film that I sort of started to hear those regrets," Cooper said. Specifically, she and her mother — who had lost the embittered, public custody battle with the Vanderbilts — at one point did not speak for what he estimated to be 18 years.

Vanderbilt also lost touch with Dodo, her beloved nanny who had raised her, and whom Vanderbilt later hired to take care of her two older sons. "Dodo died at Catholic Charities — this person who had been the closest person to my mother," he said.

That his mother had allowed people to slip out of her life has proven to be instructive to Cooper. "I had a nurse when I was a kid growing up, a nanny, for the first 15 years of my life, who I was incredibly close to," he said. "And who died just two years ago. I was there in the days before she died. I definitely learned from my mom, not having those missed connections."

Nothing Left Unsaid takes it as a given that, as Vanderbilt herself puts it, her life has been a tragedy — despite her accomplishments and a good amount of fun she has had over her 92 years. Cooper said that based on her contested childhood, she was burdened by "the longing for something that never was," he said. "And I think that's what is at the core of the sadness." As her life proceeded, devastating events added up: "My brother's suicide, and my dad's death," Cooper said. But he traces her initial heartache to Vanderbilt's father's death when she was 15 months old. "I think it goes back to that quote from Mary Gordon, which is 'A fatherless girl thinks all things possible and nothing safe,'" he said. "That is at the core of my mom's existence. And I always saw that in her eyes. I mean, I could always see that slight melancholy, slight sadness. Like a shadow passing by in her eyes."

And yet, he said: "She has great joy, and is the most optimistic person who thinks great love is right around the corner at 92. I mean, literally believes this. And I believe it too for her, because nothing would surprise me with my mom."

8. Cooper, on the other hand, has not inherited her optimism.

"I've grown up in complete reaction to that, and am a complete catastrophist and believe the worst is about to occur at any second," he said.

And Cooper, who has reported from dozens of war zones, means literal catastrophes.

"Like, I want to have a stockpile of food in my basement," he said. "If a bomb went off here right now, I have the number for CNN for where to call in to start reporting. I want to be prepared for any eventuality. And I'm so egotistical that I believe that I would somehow survive the bomb blast, so I would continue to report."

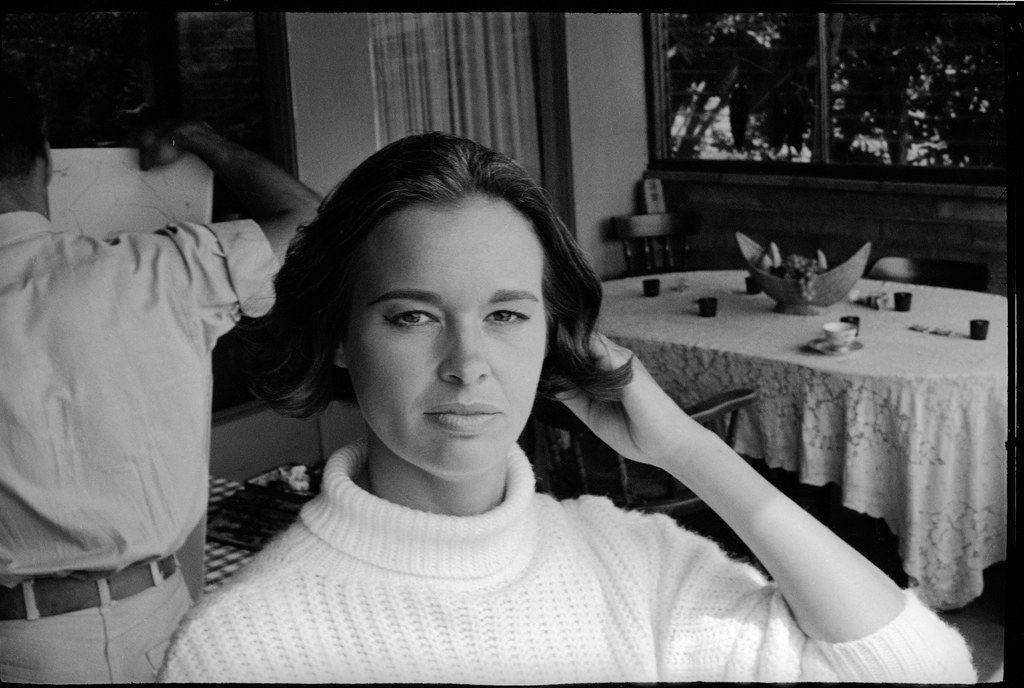

9. Cooper is a recognizable public figure; his mother, at 92, has been famous nearly all her life.

They seem to handle their fame similarly: by pretending it's not there.

"I think celebrity is like gangrene," Cooper said. "You have to watch the spread of it or it will infect your entire body. And it gives you this sense of entitlement that is sick, and totally antithetical to being a reporter. So there's no good that can come of thinking about yourself in that way.

"Honestly, people come up to me on the street all the time and say hi, and I say hi, and I just pretend that they know me somehow," he continued. "Or maybe I know them. I have such a bad memory, I very well may know them, so I greet everybody with equal enthusiasm!"

As for Vanderbilt's daily life, Cooper thinks the reason no one had thought to make a documentary about her is that they don't know about her private world. "People probably imagine she lives this glamorous life of going to parties and having lunches with ladies and stuff," he said. "She hasn't done that stuff in my entire lifetime."

She has recently discovered Judge Judy, he said; and even more recently, Dr. Phil. "She works all day long in her studio, painting or drawing. She'll eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for lunch," Cooper said. "She's amazingly present, but she's also replaying the past constantly, and rethinking things. She very much lives in her own head. You know, she's not a mom who calls me up and asks me what's going on. I'm the one who calls her or emails her. I've always understood that about her, and been very sensitive to it and protective of her."

And anyway, she wouldn't have let anyone else do this documentary. "To be shot without makeup at 92 for a woman who's been a great beauty her entire life, and still at 92 looks amazing — she had to think about it for a second," Cooper said. "Then she was, like, Yeah, why not, of course."