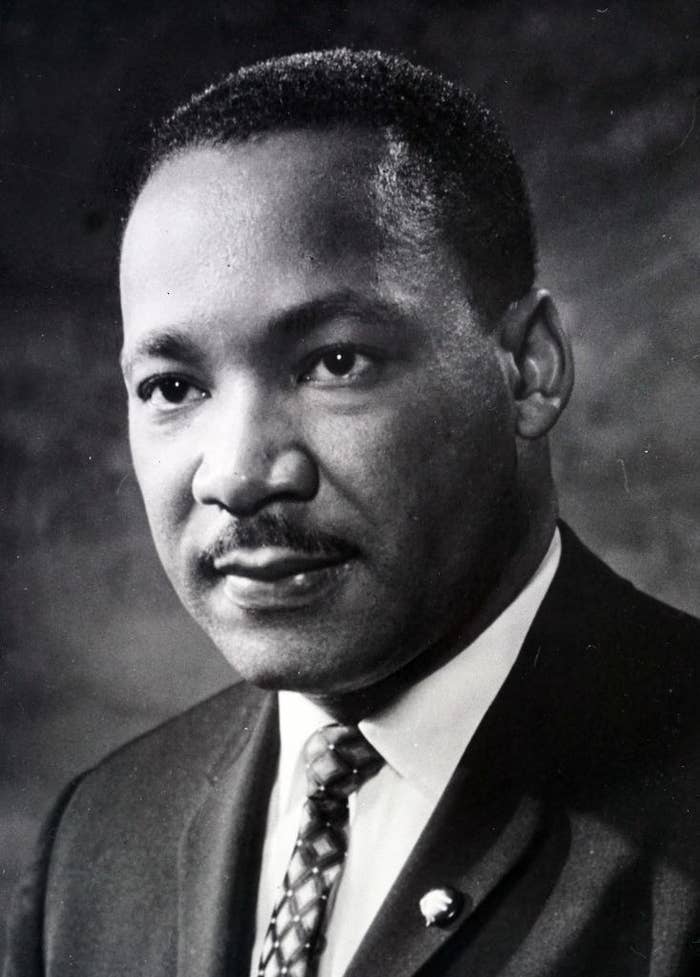

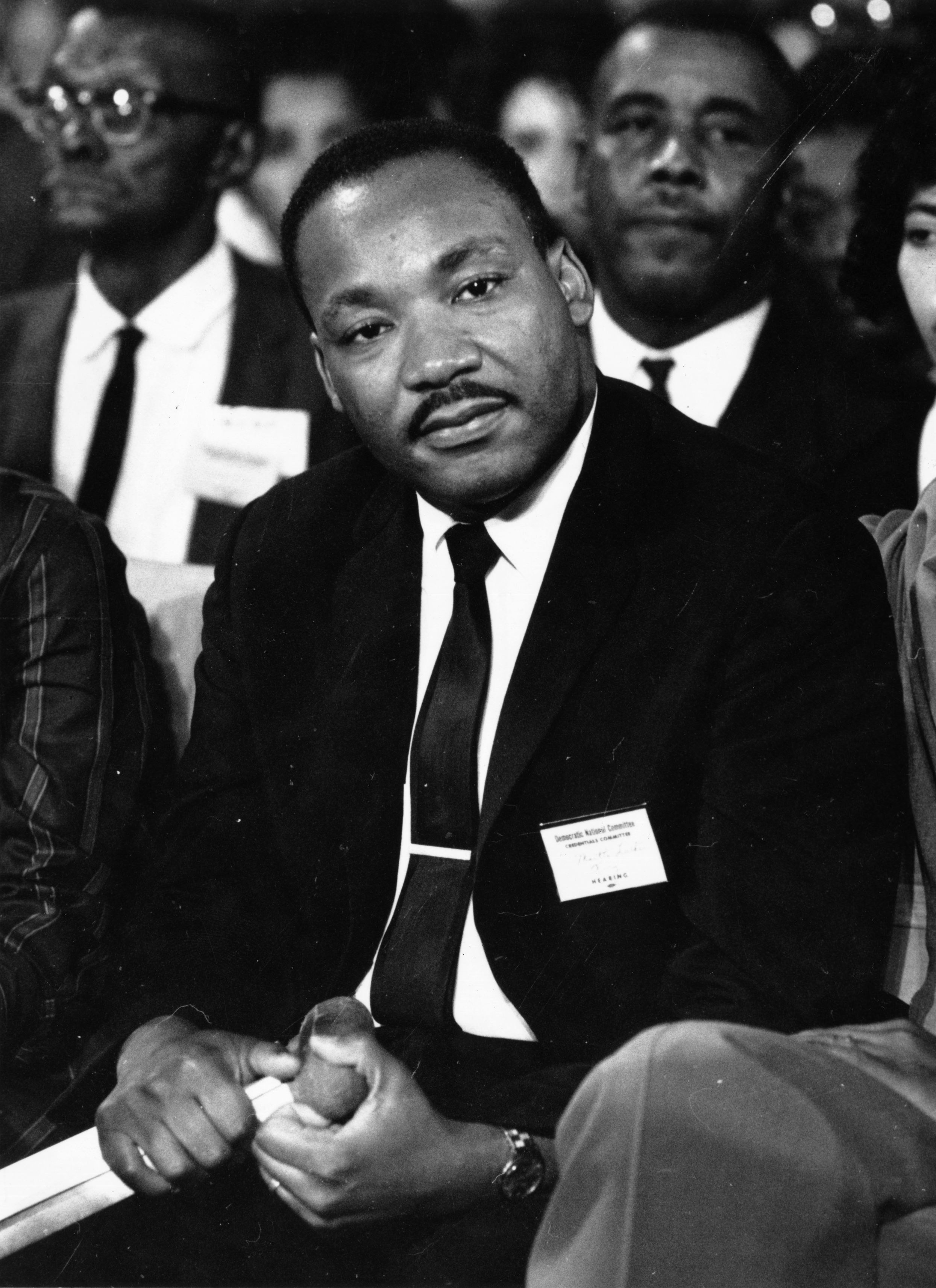

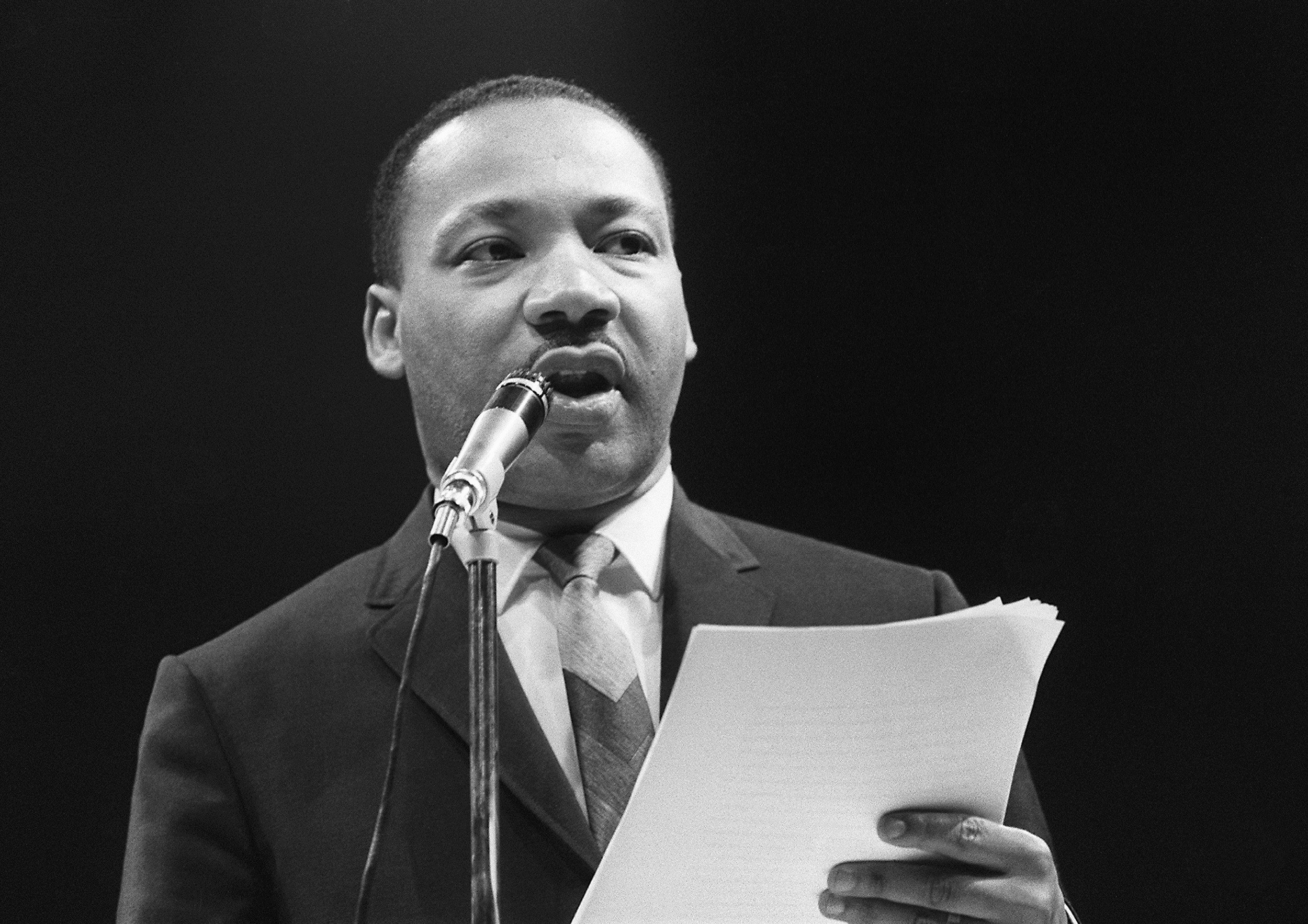

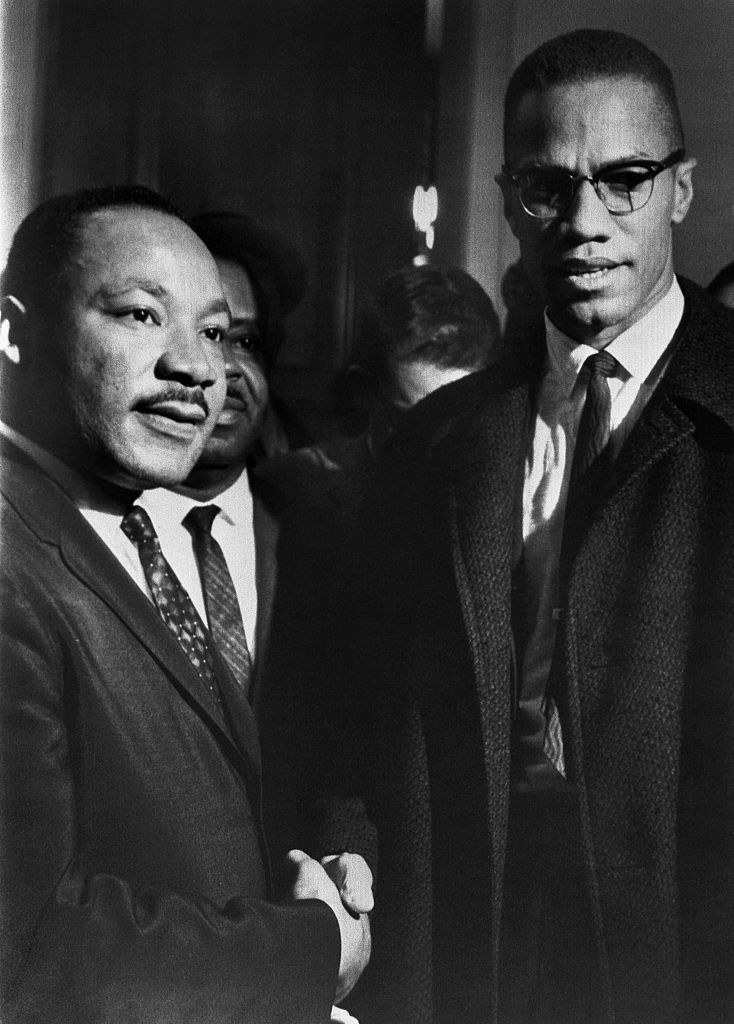

There's no doubt that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is one of, if not the most, influential Black activist of all time. For this part of our Black History Month True Crime series, I will explore his life, his activism, the enemies he made along the way, as well as his assassination, and the following case. Let's get into it.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was born Michael King Jr. on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. He came from a middle-class upbringing that was deeply involved in the Southern Black Baptist ministry, where his father and maternal grandfather were both Baptist preachers. His father, Rev. Michael King Sr., after traveling to Berlin, Germany, became inspired by the work of Protestant icon Martin Luther. When he returned to America, he changed his name and his son's name to Martin.

"The community in which I was born was quite ordinary in terms of social status," Dr. King wrote in his autobiography. "No one in our community had attained any great wealth. Most of the Negroes in my hometown who did attain wealth lived in a section of town known as 'Hunter Hills.' The community was characterized with a sort of unsophisticated simplicity. No one was in the extremely poor class. It is probably fair to class the people of this community as those of average income."

Dr. King's solid upbringing, however, did not stop him from being exposed to the common overt prejudices of the South. He wrote recollections of the time one of his white friends expressed that they could no longer play with him, due to them attending segregated schools.

Dr. King also wrote that it was not only him that resented segregation and systemic racism, but his father Rev. Martin King Sr. "had not adjusted to the system, and he played a great part in shaping my consciousness."

As Dr. King got older, he began to not only notice racial injustice but economic injustice as well. "I had also learned that the insufferable twin of racial injustice was economic injustice," Dr. King penned. "Although I came from a home of economic security and relative comfort, I could never get out of my mind the economic insecurity of many of my playmates and the tragic poverty of those living around me."

Before heading off to college, Dr. King went to work on a tobacco farm in Simsbury, Connecticut, to earn some money for school. He wrote, "One Sunday we went to church in Simsbury, and we were the only Negroes there. On Sunday Mornings I was the religious leader and spoke on any text I wanted to 107 boys. I had never thought that a person of my race could eat anywhere, but we ate in one of the finest restaurants in Hartford."

This summer experience only deepened Dr. King's festering hatred toward racial segregation. "I could never adjust to the separate waiting rooms, separate eating places, separate restrooms," he wrote.

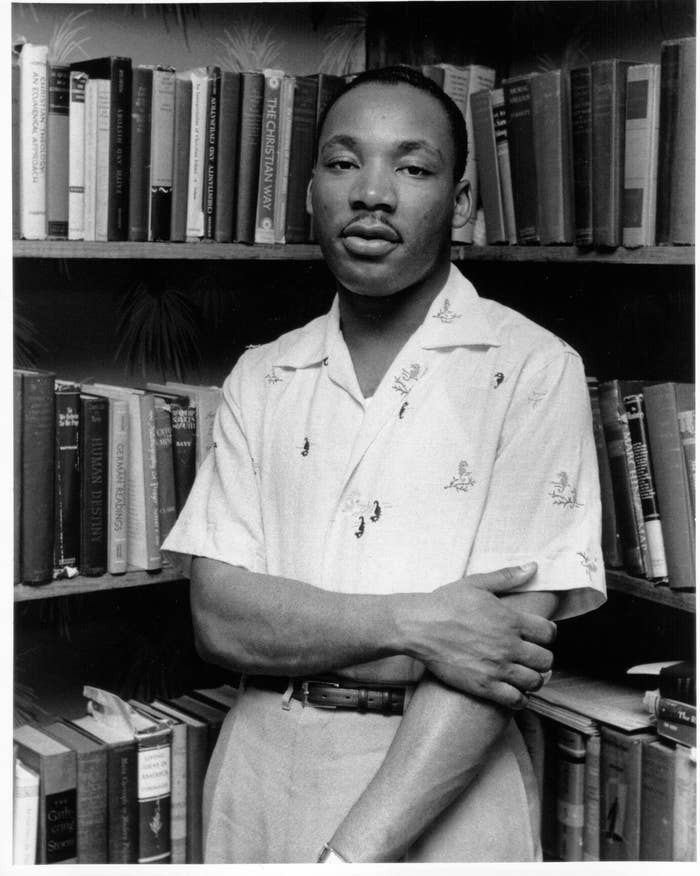

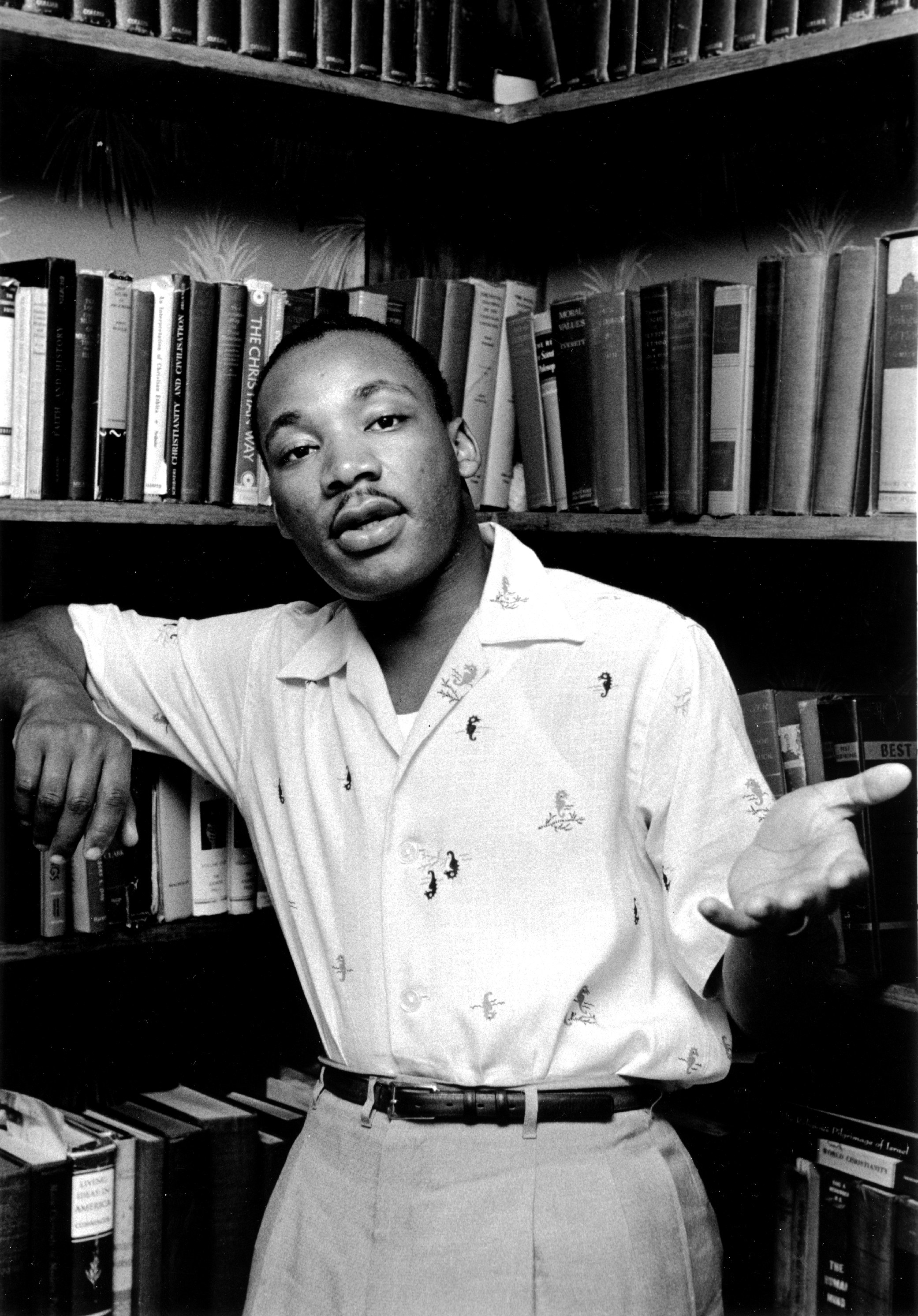

At the age of 15, Dr. King began attending Morehouse College in Atlanta after skipping two grades and being one of the top students in his high school. King's days in college were exciting ones for him; it was a place that he felt had a free atmosphere and the first place where he had his first frank discussion on race.

During his freshman year in 1944, Dr. King had a substantial concern for racial and economic justice. He would then read Henry David Thoreau's essay "On Civil Disobedience" for the first time. The piece moved Dr. King so much that he reread the work several times. It was his first time coming in contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance, and he was fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system.

"Whether expressed in a sit-in at lunch counters, a freedom ride into Mississippi, a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, these are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice," Dr. King wrote.

Upon his senior year of college, Dr. King decided to join the ministry. The president of Morehouse College, one of Dr. King's mentors, Benjamin Mays, was a social minister involved in activism. "I had felt the urge to join the ministry from my high school days, but accumulated doubts had somewhat blocked the urge." Dr. King wrote. "Now it appeared again with an escapable drive. I felt a sense of responsibility which I could not escape."

On September 14, 1948, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, to begin his intellectual quest for a method to eliminate social evils. During his time in seminary, Dr. King spent most of his time reading different philosophers, from Aristotle to Karl Marx, to find an answer that would help him reach clarity on how he could effectively resist a broken system. It was also the first place where he was exposed to the pacifist position when he attended a lecture by Dr. A.J. Muste.

"During this period I had about despaired of the power of love in solving social problems," wrote Dr. King. "I felt that the Christian ethic of love was confined to individual relationships. I could not see how it could work in social conflict."

"Like most people, I had heard of Gandhi, but I had never studied him seriously," Dr. King explains. "As I read I became deeply fascinated by his campaigns of nonviolent resistance." The concept of Satyagraha (Satya meaning truth equalling to love and Agraha meaning force; Satyagraha comes out to truth force or love force) was immensely influential to Dr. King.

"Gandhi was probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force on a large scale," Dr. King wrote. For him, Gandhi's teachings of love, and nonviolence, played a significant role in showing him the method of social reform that he had been seeking since he attended seminary.

Upon graduating from Crozier in May 1951, Dr. King had a strong desire to teach in a college or in a school for religion. While he had some knowledge of the field, Dr. King knew that he needed to do more intensified studying at a graduate school in order to be qualified to teach. His sights were set on attending Boston University, mainly because many of his philosophical revelations came from a few faculty members. One of his most influential professors at Crozier graduated from Boston, giving King a desire to attend his professor's alma mater.

In January 1952, Dr. King met and fell in love with the love of his life, Coretta Scott. It's tough to give an exact date as to when the couple met, but experts say that the two met on a blind date across town at the New England Conservatory of Music under cloudy wet midday skies.

In 1954, Dr. King began giving trial sermons in Alabama and Michigan, with many other states expressing interest in the young minister. On April 14, 1954, King accepted a pastoral job at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, as the church's new pastor and moved reluctantly with Coretta to start their new life. "Finally we agreed that, in spite of the disadvantages and inevitable sacrifices, our greatest service could be rendered in our Native South. We came to the conclusion that we had something of a moral obligation to return — at least for a few years," wrote Dr. King.

This was a significant turning point for Dr. King as he made his way back to the heavily segregated South. He wanted to use all that he had learned while away at school to help make a positive impact on the movement toward social justice. "Moreover, despite having to sacrifice much of the cultural life we loved, despite the existence of Jim Crow, which kept reminding us at all times of the color of our skin, we had the feeling that something remarkable was unfolding in the South, and we wanted to be on hand to witness it," Dr. King penned.

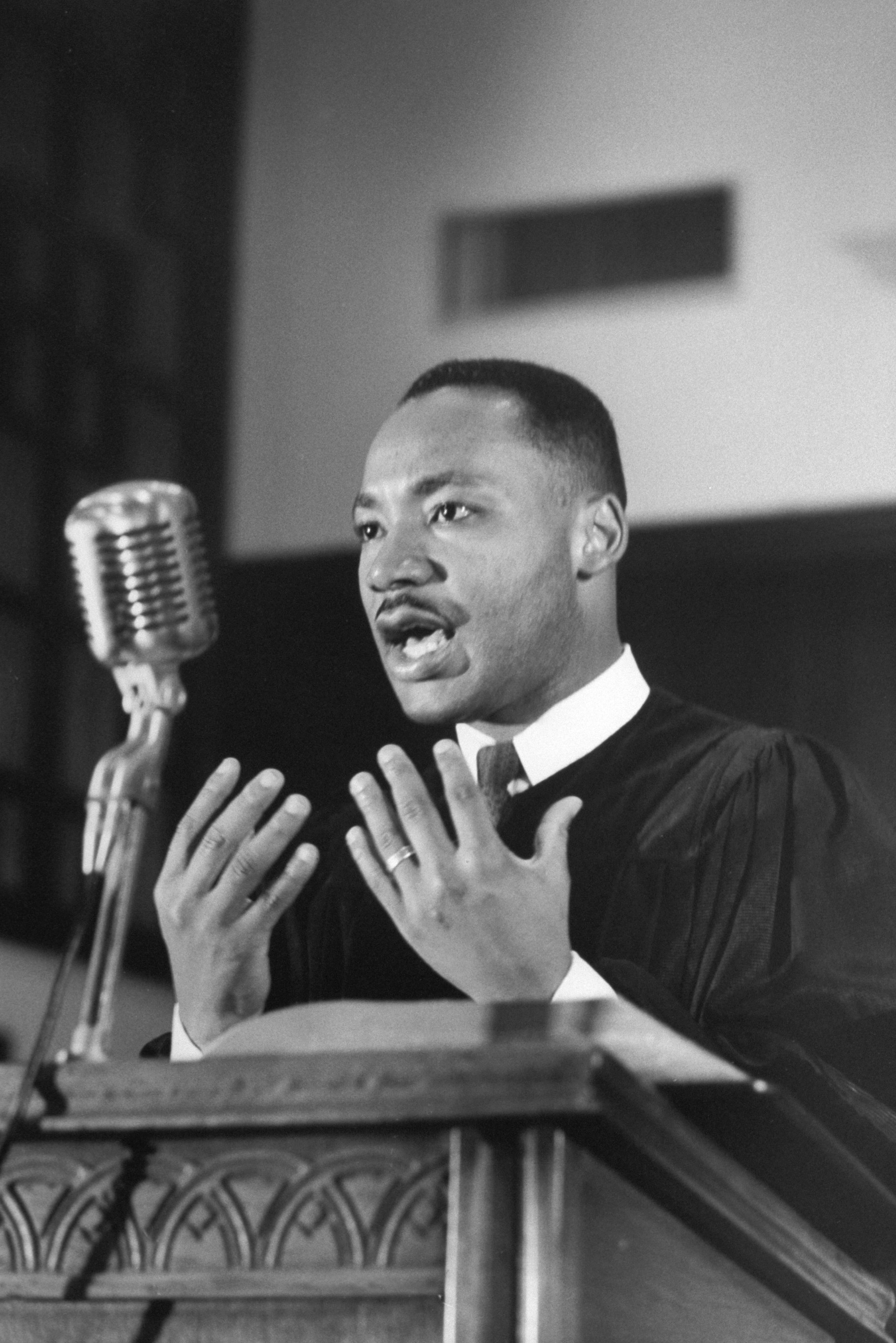

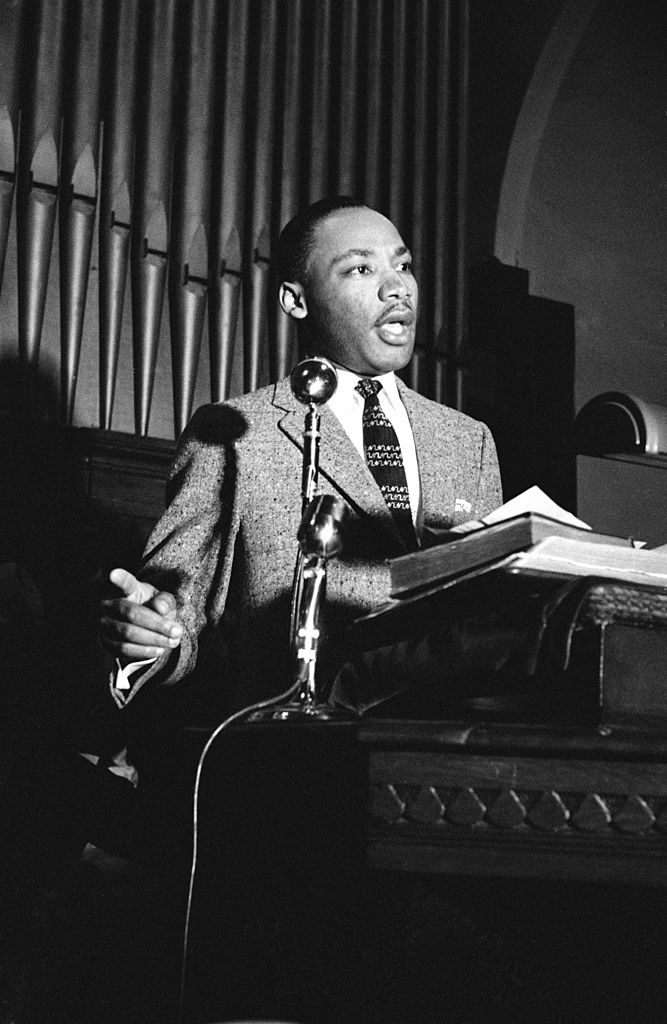

As Dr. King began his pastoral journey in Montgomery, preaching his first sermon as Dexter's new pastor on Sunday in May 1954, he hit the ground running doing everything he could to change the culture of his new church in hopes to make it more of a communal place of worship. "The first few weeks of the autumn of 1954 were spent formulating a program that would be meaningful to this particular congregation," explained Dr. King. "I was anxious to change the impression in the community that Dexter was sort of a silk-stocking church catering only to a certain class. Often it was referred to as the 'big folk church.'"

As Dr. King settled into his new church and congregation, he got heavily involved with the current social problems. "I took an active part in current social problems," penned Dr. King. "I insisted that every church member become a registered voter and a member of the NAACP and organized within the church a social and political action committee — designed to keep the congregation intelligently informed on the social, political, and economic situations."

Implementing this new social and political action committee helped show the congregation the importance of the NAACP (The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), the necessity of being a registered voter, and the power of sponsoring forums and mass meetings to discuss major issues. It was here where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became more involved with the NAACP and began the activism journey that we revere and celebrate him so much for.

The Alabama Council on Human Relations had Dr. King's attention, in which he decided to join the organization in tandem with his membership with the NAACP. It was an interracial group concerned with human relations in Alabama and implicated educational methods to achieve its goals. According to Dr. King, "it sought to attain, through research and action, equal opportunity for all the people of Alabama." After only a few months with the council, they elected Dr. King to be their vice president.

On the contrary, many other Black people felt that Dr. King's dual membership was conflicting. "I was surprised to learn that many people found my dual interest in the NAACP and the Council inconsistent," Dr. King expressed. "Many Negroes felt that integration could only come through legislation the chief emphases of the NAACP. Many white people felt that integration could only come through education — the chief emphases of the Council on Human Relations."

After about a year in Montgomery, Dr. King became a proud father to his first daughter, Yolanda "Yoki" Denise King, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott began. On December 1, 1955, Mrs. Rosa Parks, one of the integral catalysts for the civil rights movement, refused to give up her seat to a white passenger, resulting in her arrest. "One can never understand the actions of Mrs. Parks until one realizes that eventually the cup of endurance runs over, and the human personality cries out, 'I can't take it no longer,'" penned Dr. King.

"I listened, deeply shocked, as he described the humiliating incident," inscribed Dr. King. "'We have taken this type of thing too long already,' Nixon concluded, his voice trembling. 'I feel that the time has come to boycott the buses. Only through a boycott can we make it clear to the white folks that we will not accept this treatment any longer.' I agreed that some protest was necessary and that the boycott method would be an effective one."

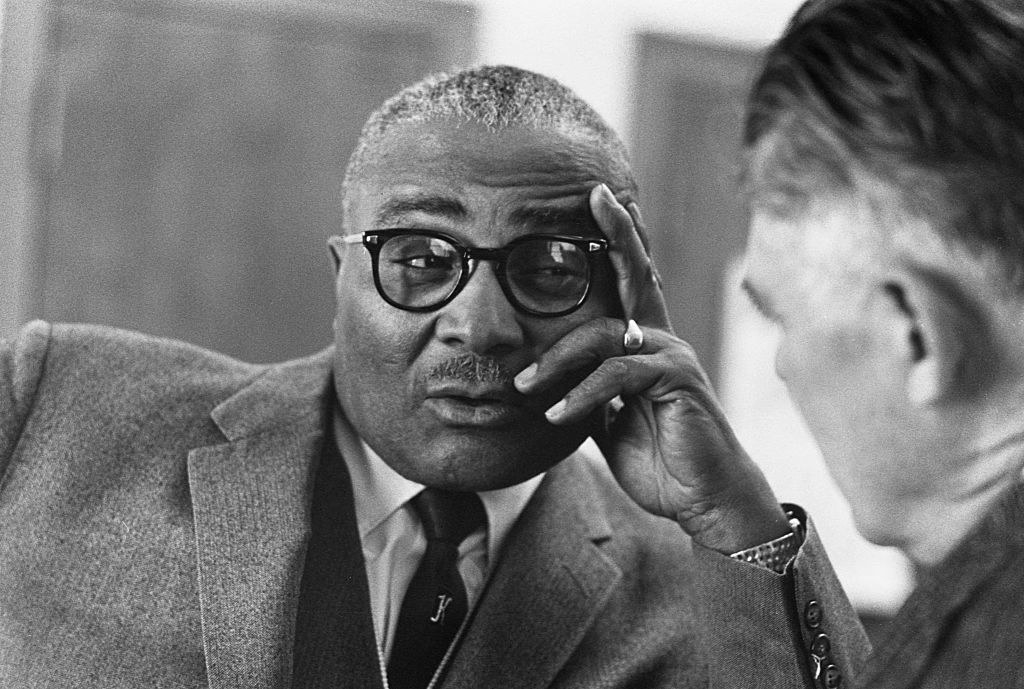

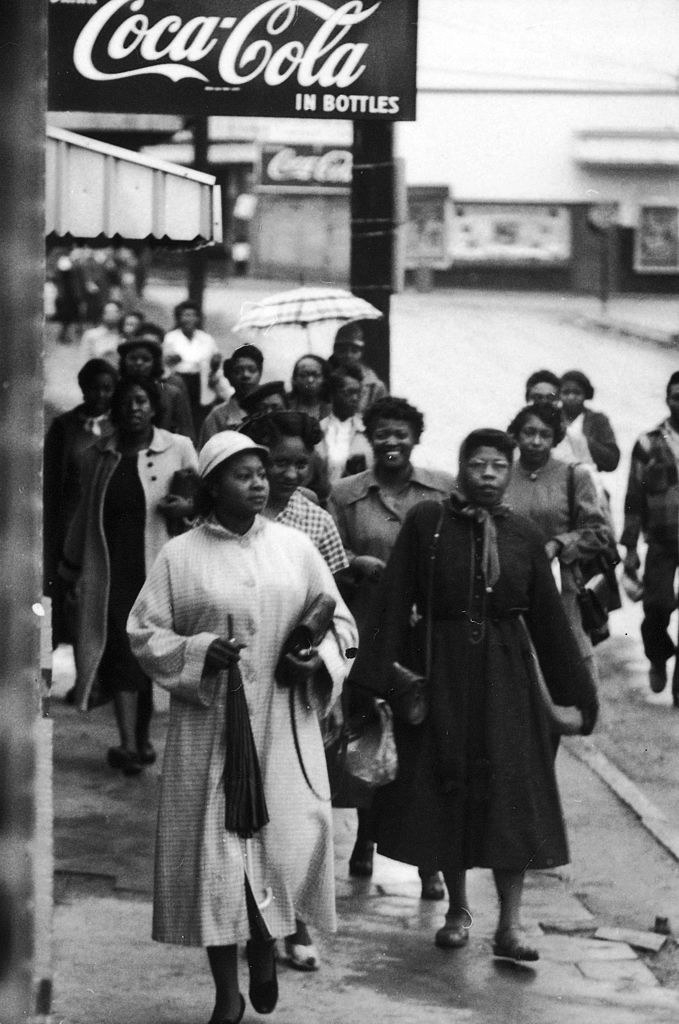

The Montgomery Bus Boycott started on December 5, 1955, and lasted until December 20, 1956. It's regarded as the first large-scale US demonstration against segregation. Around 40,000 Black people, who were the majority of the city's bus riders, boycotted the buses on December 5. During that afternoon, there was a mass meeting where Dr. King and other Black civic leaders met to form the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and elected Dr. King as their president.

E.D. Nixon felt another way about it. "We are acting like little boys," he said. "Somebody's name will have to be known, and if we are afraid we might just as well fold up right now. We must also be men enough to discuss our recommendations in the open; this idea of secretly passing something around on paper is a lot of bunk. The white folks are eventually going to find it out anyway. We'd better decide now if we are going to be fearless men or scared boys."

Originally, the demands didn't include changing the segregation laws; instead, the group demanded guaranteed better treatment by the bus operator, that passengers were seated on a first-come-first-serve basis (still segregated), and for Black bus operators to be employed at predominantly Black bus stops. After the group's meeting, Dr. King was certain that a big change was on the rise.

While the Black community accounted for 75% of the city's bus riders, the city resisted complying with the group's demands. To sustain the protest, Black civic leaders developed carpools, and the city's Black cab drivers only charged 10 cents, the cost of the bus fare, for Black riders. However, a good majority of Black residents chose to walk instead of riding the bus to get to work or any other destination, and regular meetings were held to help keep all Black residents mobilized around the boycott.

When the group organized the private carpool, there was an overwhelming response of volunteers willing to utilize their automobiles for the cause. "The response was tremendous. More than a hundred and fifty signed slips volunteering their automobiles," Dr. King wrote. "Some who were not working offered to drive in the car pool all day; others volunteered a few hours before and after work." The Montogomery Bus Boycott was a movement where everyone in the Black community was heavily involved, with the hopes of making real changes.

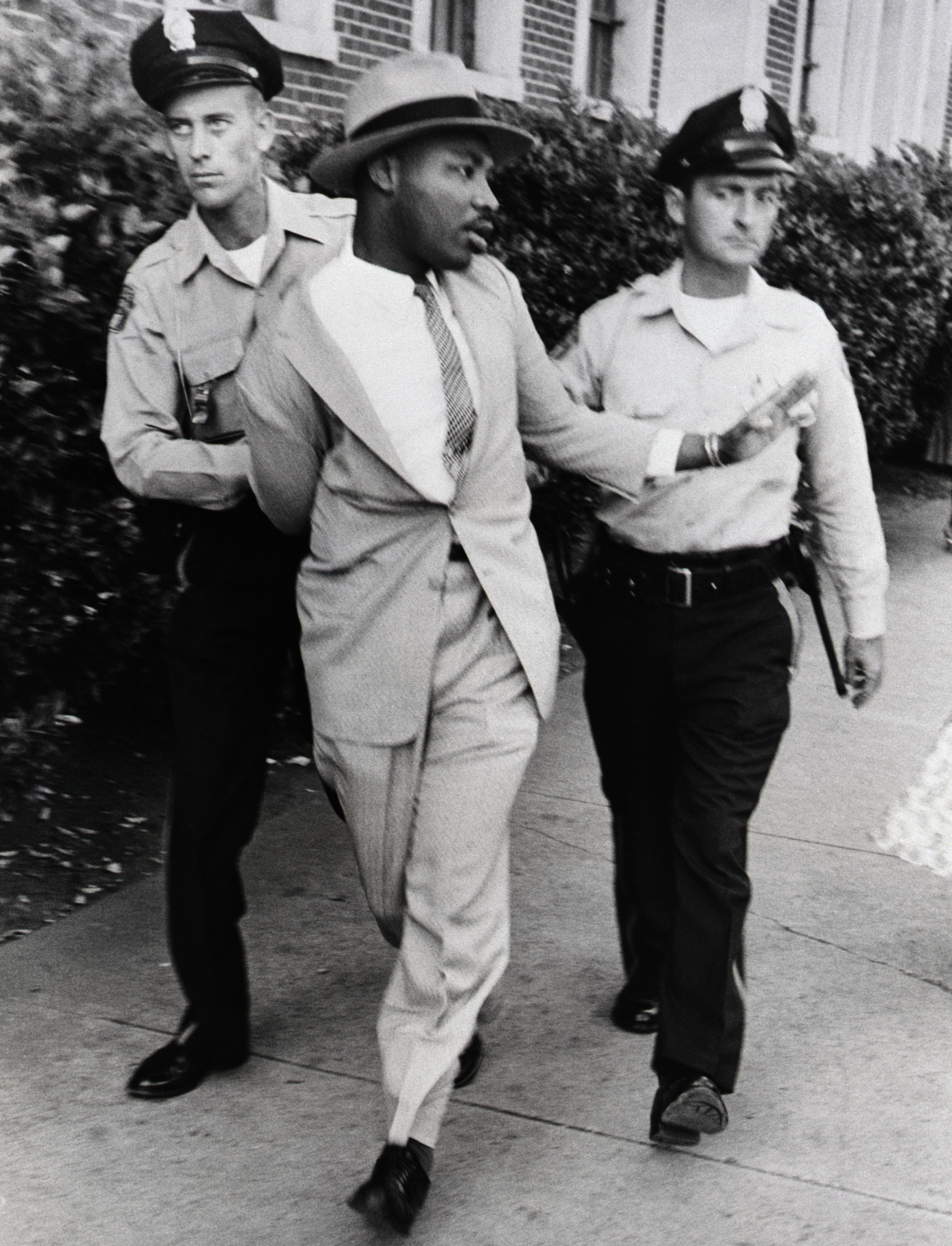

However, in the midst of the boycott and Dr. King's ascending fame, he gained many enemies from the disgruntled white community. His home was bombed, but no one was hurt thankfully.

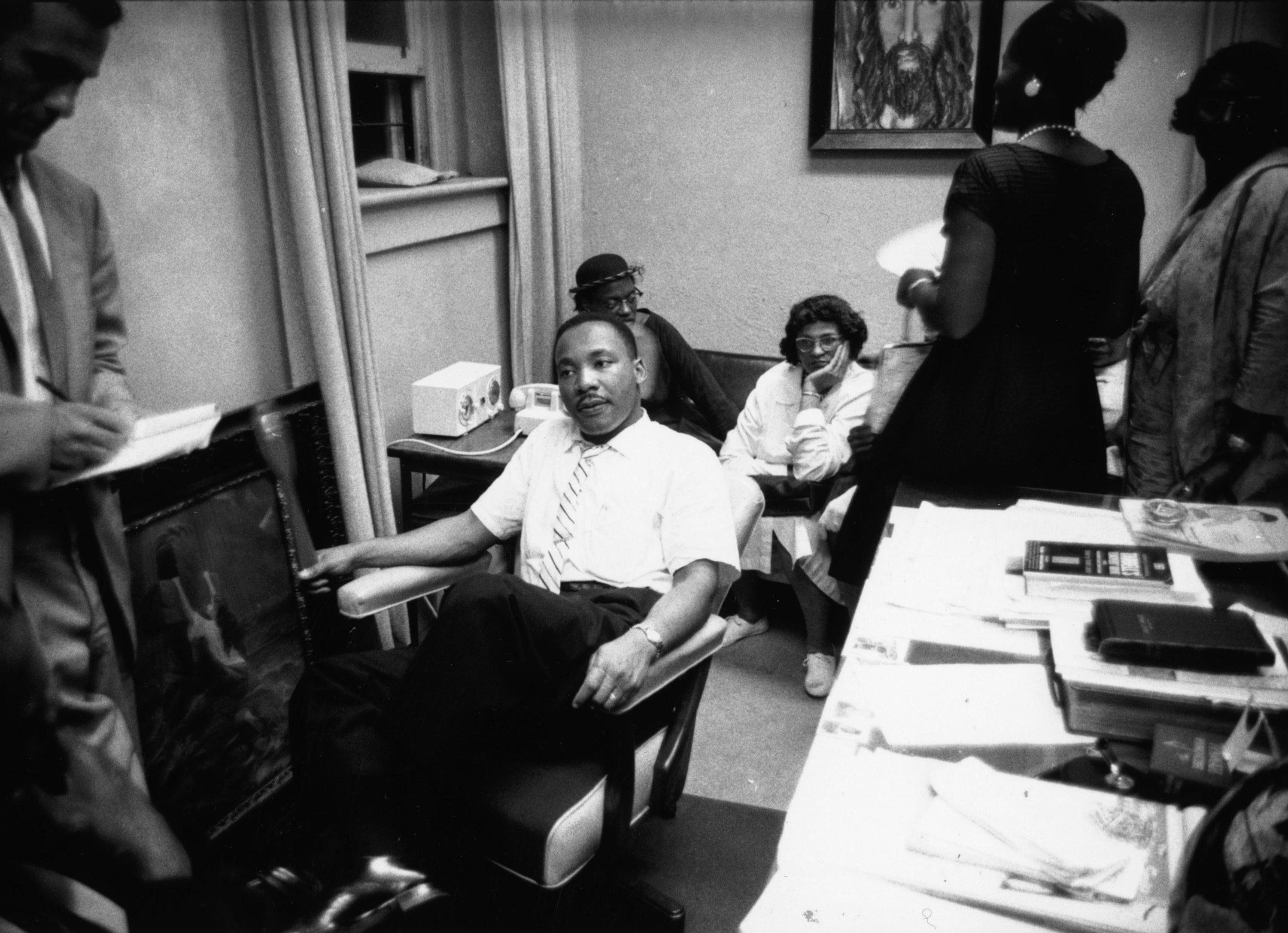

That didn't stop Dr. King though. To keep the momentum going and capitalize on the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Dr. King and other civic leaders decided to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to coordinate the action of local protest groups throughout the South. It gave Dr. King a base of operations throughout the South and a national platform for him to speak.

Through the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King was able to lecture in all parts of the country and abroad. The organization drew from the power and influence of Black churches to support their activities. The SCLC organized a plethora of campaigns to help move toward social justice.

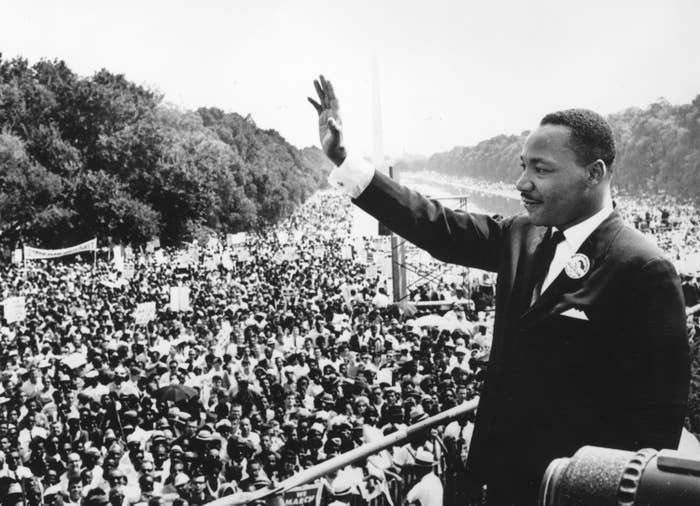

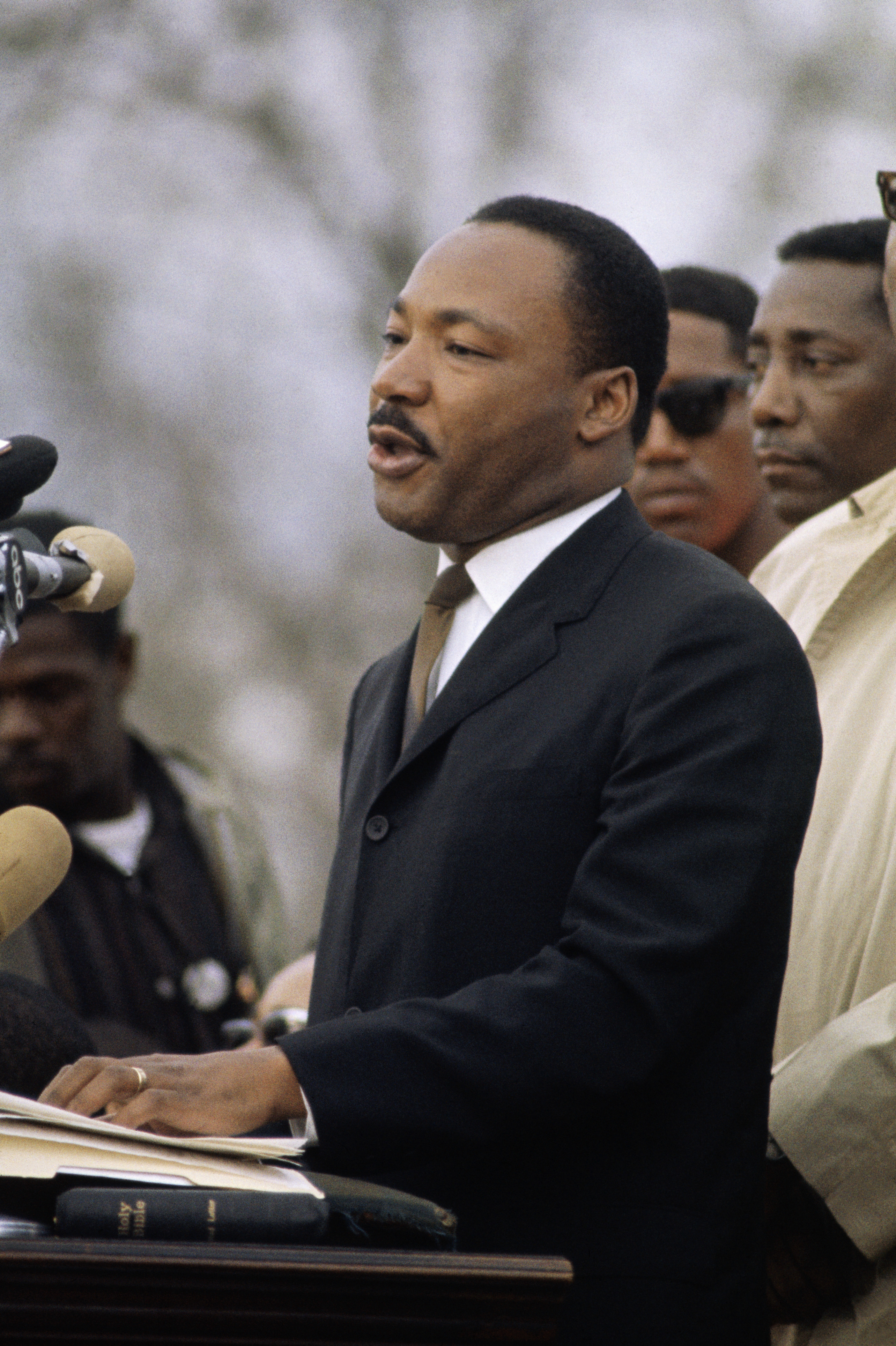

The Southern Christian Leadership Council also joined many other local movements around the South, influencing many of Dr. King's most influential marches from his well-known Selma to Montgomery March to his most powerful March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Dr. King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

View this video on YouTube

The integral groundwork for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 during the civil rights struggle was laid, thanks to the SCLC bringing visibility to the situation.

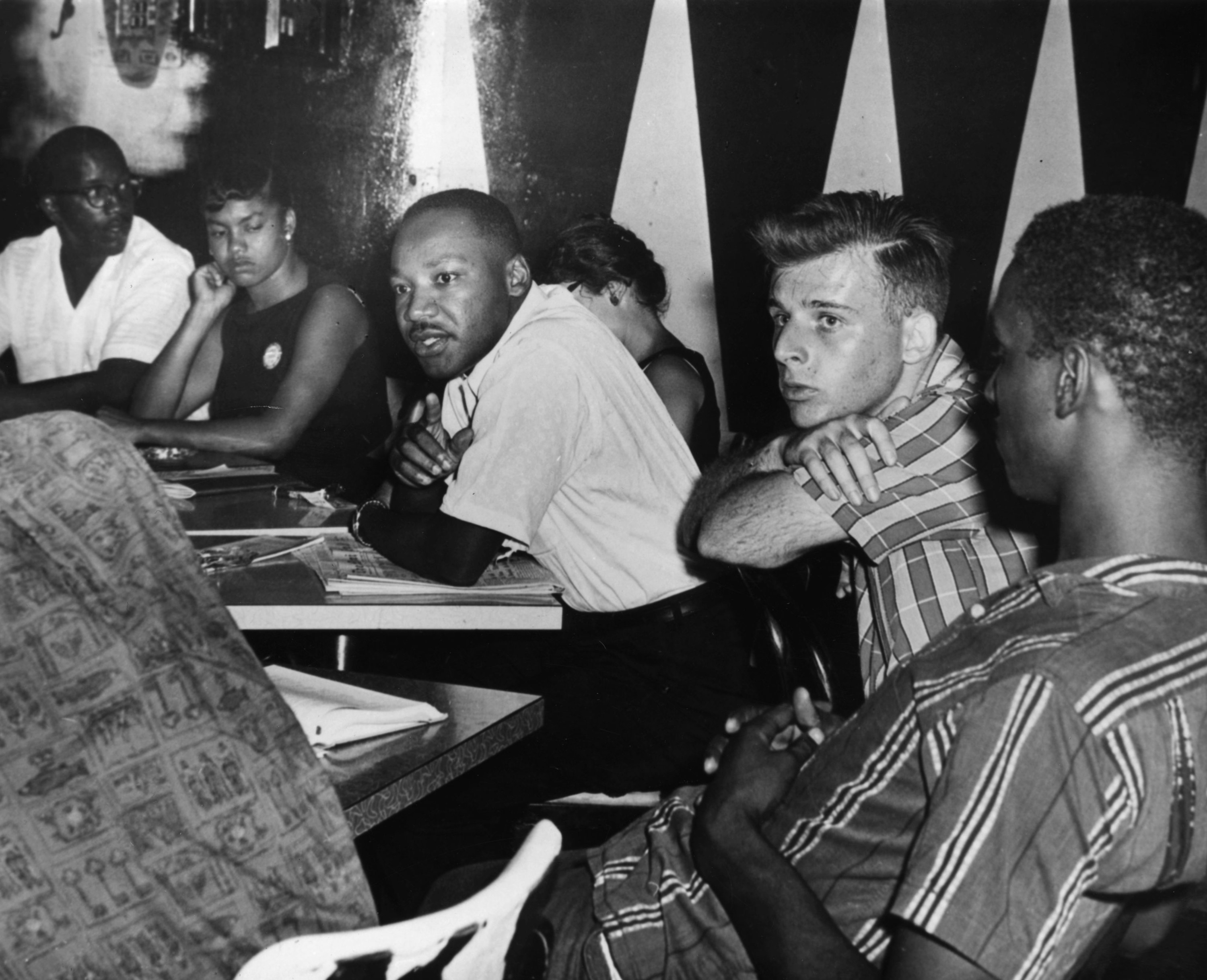

In 1962, the organization began broadening its focus on economic inequality. At this time, Dr. King's fame and influence had reached its zenith, getting the attention of news media and national television, specifically producers who wanted to build social change. He understood how to use the media to his advantage to bring national and international attention to the struggle for civil rights, and his well-publicized methods of active nonviolence (sit-ins, protests, marches).

While Dr. King and his associates in the Southern Christian Leadership Council were making lots of headway with the civil rights movement, a less than metaphorical target had been placed upon the back of Dr. King. His ideas of desegregation, ensuring every Black resident had voting power, and overall liberating movements to end social injustice angered many opposing parties. The most notable was the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which went to great lengths to tarnish Dr. King's image.

In April 1964, when Dr. King said the FBI was "completely ineffectual in resolving the continued mayhem and brutality inflicted upon the Negro in the deep South," the government agency began to ramp up their operations against him.

Under the FBI's domestic counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO), Dr. King was subject to all sorts of FBI surveillance. From wiretaps to planting agents everywhere that Dr. King was speaking or protesting, the FBI pulled out all the stops to find any evidence that he was influenced by Communists. However, outside of finding evidence of extramarital affairs, which they later tried to use against him, there was no evidence of Communist influence.

Soon after, Hoover assigned agents to find "subversive" evidence against Dr. King, and Attorney General Robert Kennedy authorized wiretaps in Dr. King's home and the Southern Christian Leadership Council's offices in 1963.

The FBI even went as far as sending Dr. King an anonymous tape recording of him drinking and partying, acting in a unprofessional manner, with a letter attached that was interpreted as encouragement to commit suicide to prevent public embarrassment. AKA, the FBI tried to blackmail Dr. King into killing himself.

Also, in August 1967, the FBI organized COINTELPRO against "Black-Nationalist Hate Groups," which was an excuse to target Dr. King, SCLC, and all other civil rights leaders.

On April 3, 1968, Dr. King arrived in Memphis, Tennessee, to conduct a march the following Monday on behalf of striking Memphis sanitation workers, where he would deliver his acclaimed "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech. As Dr. King prepared to leave the Lorraine Motel to have dinner, he stepped out on the balcony to speak to his SCLC colleagues in the parking lot below. A gunman fired a single shot to the face of Dr. King. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:05 p.m.

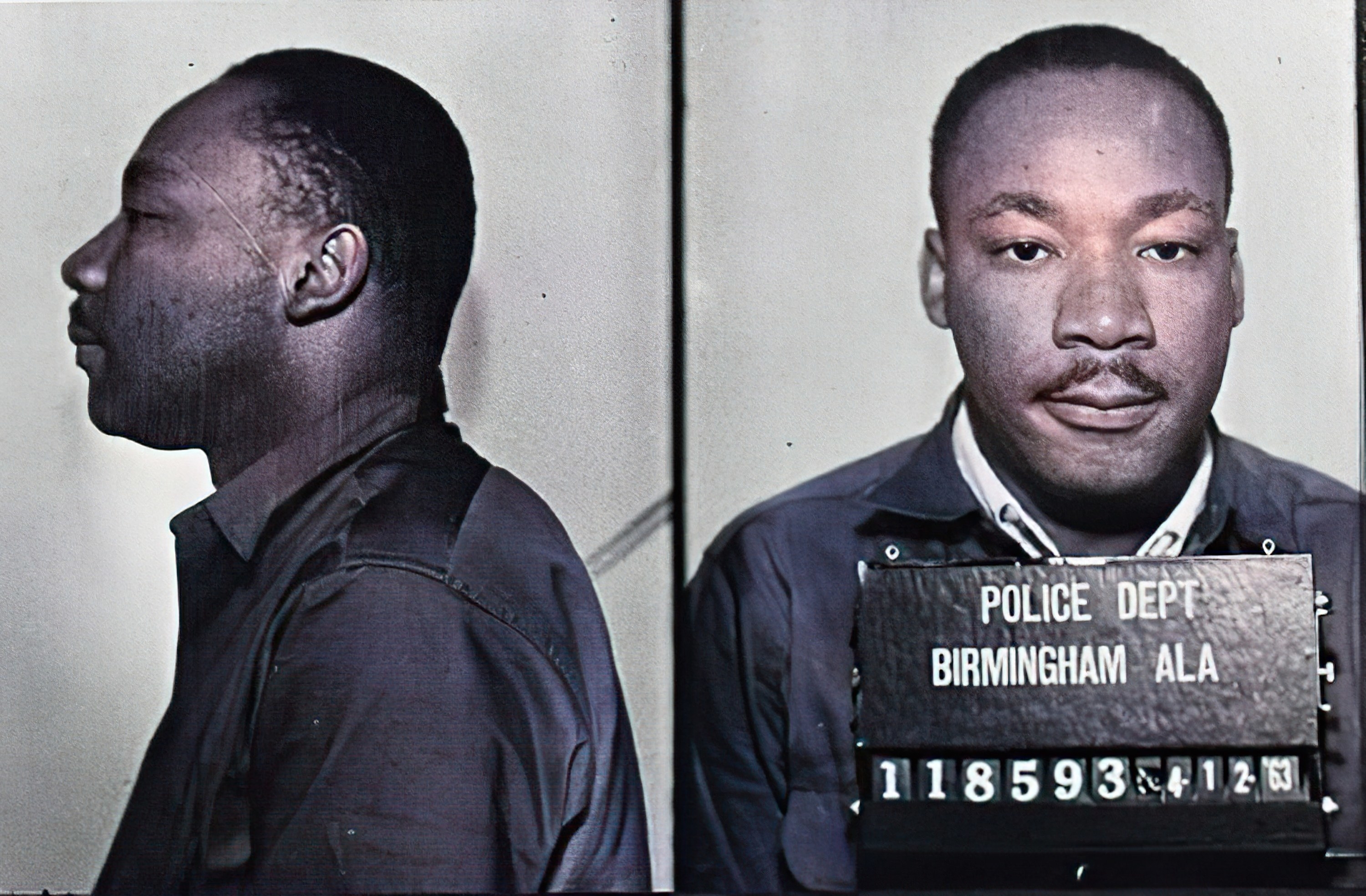

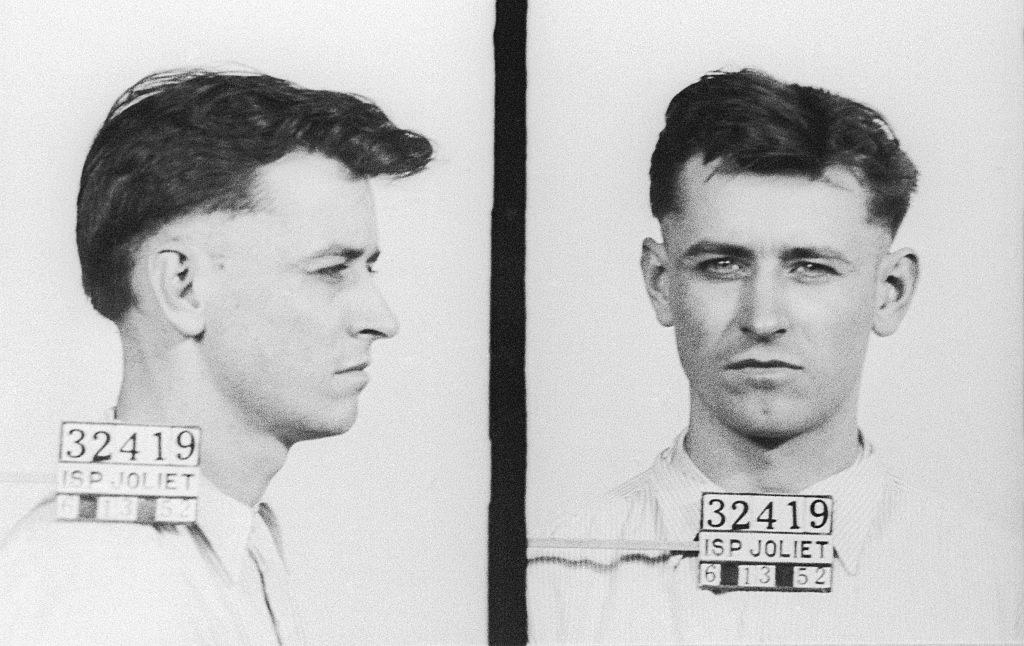

Sometime after the assassination, the FBI discovered a kit containing a 30.06 Remington rifle next door to the boarding house, leading to the biggest investigation in FBI history. The investigation led the FBI to an apartment in Atlanta, in which they found the fingerprints of James Earl Ray. He was a fugitive who escaped a Missouri prison in April 1967. Memphis police and the FBI also discovered that Ray had been placed in a second-floor boarding room across the street from the Lorraine Motel prior to Dr. King's assassination.

While there is evidence that shows how Dr. King was assassinated, there are still a few details that many still debate today. On March 13, 1969, just days after his sentencing, Ray recanted his guilty plea, saying he was coerced into confessing. Ray offered to prove his innocence, claiming that he wasn't at the scene. He claimed to have been set up as a decoy by a group of conspirators, one of which being the true gunman, a mystery man that Ray only knew as Raoul, whom he first met in Montreal in 1967.

However, even Dr. King's family felt something didn't add up with his assassination; members of his family later came to the defense of Ray. In 1997, Dr. King's son Dexter met with Ray and publicly joined Ray's plea to reopen his case.

Since it was the FBI that spent years aiming for Dr. King, many people are suspicious of any government investigation. It would be like you committing murder and then investigating yourself.

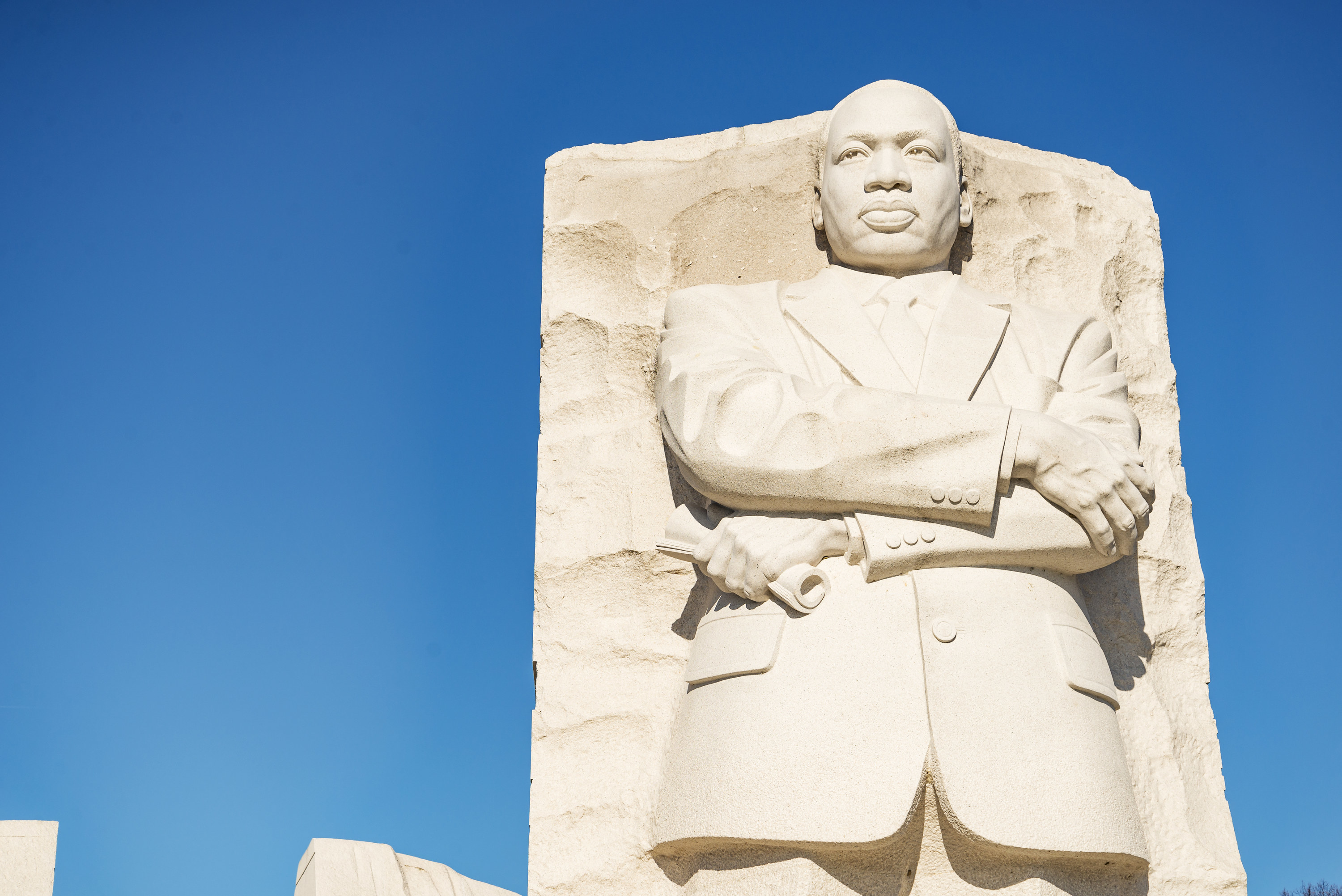

Although there are some who believe Dr. King's murder was a conspiracy, the fact remains that everyone who could have been involved in his assassination is now dead and gone. Justice was supposedly served, but it left a massive hole in the hearts of many hopeful Americans who saw Dr. King as a beacon for better things to come.

However, Dr. King's legacy has lived on for generations, and his influence is as strong as it's ever been. His belief that love and nonviolence can move even the tallest mountains is something that everyone can appreciate and learn from. He taught us never to stop fighting for what we believe in, regardless of the outcome or consequences.

Make sure to head right here for more of BuzzFeed's Black History Month coverage.