Last week, BuzzFeed asked what questions you had about the UK's referendum on EU membership, and what might happen if the Leave campaign won – and quite a lot of you had things you wanted to know.

So, here's our attempt to answer some of the questions that, thankfully, you weren't too embarrassed to ask:

Question one is from Maeve McQuillan, who asks: Can the Brexit side absolutely guarantee that the residence rights of EU citizens who have been living, working, and paying taxes in the UK for years will not be affected?

The short answer: EU citizens already living and working in the UK will almost certainly keep those rights in the event of Brexit. Leading campaigners for Vote Leave, Leave.EU, and UKIP have all promised this, and there are also some protections in international law.

The slightly longer answer: One of the central principles of the EU is that citizens in one EU state have the right to live and work in any other EU state without restriction. That's why campaigners for Leave say the UK can't control economic migration to the UK while it is an EU member.

Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, the leading politicians of Vote Leave, have called for a points-based immigration system should the UK vote Brexit, which would end the automatic right for EU citizens to live and work in Britain. However, both pledged the system would not affect EU nationals already "lawfully resident in the UK" at the time of the vote.

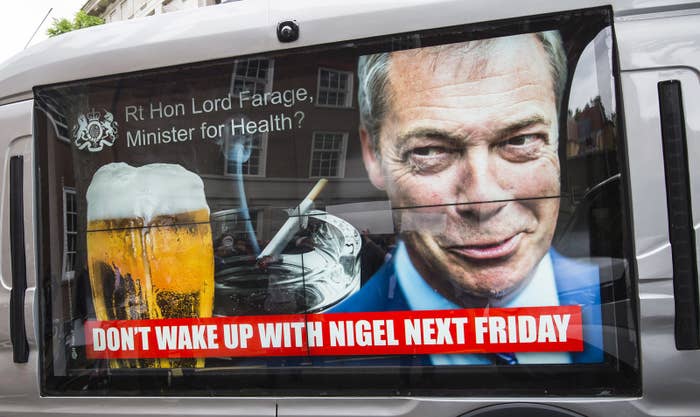

Nigel Farage, the leader of UKIP, has been expressing a similar view for several years, pledging in 2014 that even if the EU threatened to remove residency for UK citizens in Spain, "we believe in British justice and we believe that anyone who has come to Britain legally has the right to remain."

EU citizens who have lived and worked in the UK for five years or more have the option of applying for permanent resident status (the first step towards citizenship). EU nationals with this status also have extra protection under the European Convention of Human Rights and other international law, in case a future government should seek to change the Leave camp's policy.

Question two comes from @LouiseAnkersLD, who asked whether the result of the referendum will be binding on the government.

@jamesrbuk Is it binding?

The short answer: if the UK votes Leave on Thursday it will leave the EU. If not, it won't.

The slightly longer answer: Some eagle-eyed types (and lawyers) have spotted that there is nothing in the legislation setting out the EU referendum that actually forces the government to act on the result: Formally, it's a "consultative" referendum rather than a binding one.

There's a full analysis of what that means in the Financial Times, but the key sentence is this:

What happens next in the event of a vote to leave is therefore a matter of politics not law. It will come down to what is politically expedient and practicable.

In practical terms, it's simple: After a long and fractious referendum campaign, no UK government could survive ignoring the outcome of the vote. This is a position David Cameron – who supports Remain – has made very clear throughout the campaign.

When Boris Johnson suggested in February that a Leave vote could be used to trigger concessions from the EU, followed by a second referendum, Cameron said the outcome of the vote would be "final". Here's what he told parliament:

This is a vital decision for the future of our country, and I believe we should also be clear that it is a final decision ... This is a straight democratic decision — staying in or leaving — and no government can ignore that. Having a second renegotiation followed by a second referendum is not on the ballot paper. For a prime minister to ignore the express will of the British people to leave the EU would be not just wrong, but undemocratic.

In strict legal terms the referendum is not binding, and given a Leave vote would be followed by several years of fractious negotiations, MPs could challenge the terms or timescale of leaving – but in political terms, it would be difficult if not impossible for MPs to ignore the result of the referendum.

Our third and fourth questions are quite similar – about human and workers rights – so we'll tackle them together:

Can anyone on the Leave campaign promise that we’ll keep our human rights in their entirety, and if not, what will be changed?

Submitted by s4d7c9af11

Will the government be able to completely tear up the rulebook following an Out vote and force through every policy the EU has protected us from? For example, the vulnerable being kicked out of council houses.

Submitted by lara123at

The short answer: No. Although in the long term there would be no guarantee that workers' rights and human rights protections would remain as strong as they are now, many of these rights are enshrined in UK law, and so would not disappear immediately after the UK exited the EU – that would be up to a future UK government to act upon.

The slightly longer answer: Let's tackle the human rights issue first, as it's slightly fiddly. The European Court of Human Rights – whose rulings receive frequent target of ire from the Daily Mail and others – is not part of the European Union. Instead, it's part of the Council of Europe. So in theory, the UK's relationship with the court wouldn't be affected either way by a Brexit vote.

But naturally, it's all a lot more complicated than that. The role of the European Court of Human Rights is to enforce the European Convention on Human Rights, an agreement 47 countries have signed up to and that also forms the basis of the UK's Human Rights Act. The UK government has said on several occasions it would like to withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights and replace this with a "British bill of rights".

However, while the UK remains a member of the EU, it's highly debatable whether this would be possible. The European Commission has repeatedly stated its view that being signed up to the convention is an explicit obligation under EU treaties, and if the UK left the convention, it would be in breach of treaty – but as this House of Commons Library briefing note on the topic shows, this is not a view shared by the UK government or some independent experts.

In short, there'd be a big legal argument if the UK tried to leave the European Court of Human Rights while it was an EU member. That would not be the case during Brexit.

That was all very heavy, so here's a picture of a kitten:

The position on employment rights is, thankfully, simpler. Lots of the protections UK workers currently enjoy are the result of EU agreements, such as the working time directive (which caps the number of hours most employees can be made to work). All EU members must enforce these standards, so while the UK is an EU member, they are protected, even if a government might want to change or revoke them.

This means that if the UK was to leave the EU, these protections could, in time, be weakened or revoked. However, this would not happen automatically: All of the rules are codified in UK law, so a new law would need to pass through parliament to change the rules. This would also have to happen after the UK actually left the EU rather than straight after the vote – a process that could take several years.

There would be no blanket removal of either human rights or workers' protections after the UK exited the EU, but in the long term they would be more subject to a UK government who wished to change or remove them.

Question five is from leohaynes98, who asks: I’m currently studying biomedical sciences at university. If we were to leave, what would happen to British science and the grants that we receive from the EU? Would my career in science be affected or restricted in any way?

The short answer: Leading scientists and university vice-chancellors have expressed public concern about loss of funding, status, and ability to collaborate internationally following Brexit, but campaigners for Leave say any funding shortfall can be recovered.

The slightly longer answer: Here we start to get into tough territory, as we don't know the terms under which the UK might exit, how much it would hit the UK economy in the short term, what the UK's immigration policy would be, or any number of other things that would affect the state of science in Britain.

As a result, the honest answer here has to be that we don't know what would happen.

It's certainly true that UK universities receive direct funding from the EU to support scientific research. However, Leave supporters note that the UK gives more to the EU than it gets back directly (a fact Remain doesn't dispute, though the two sides disagree on the exact figures), and so say the UK government could make up this shortfall itself if the EU stopped funding UK science.

Remain campaigners warn that if Brexit caused a recession or slowdown in the UK economy, though, this would outweigh the money saved by no longer funding the EU.

A group of the UK's most prominent scientists do not seem reassured by the Leave camp's pledges in this area. A group of 13 Nobel laureates – winners of science's highest honour – wrote to The Telegraph last week warning that Brexit would threaten UK science:

“The prospect of losing EU research funding is a key risk to UK science,” they write.

“Brexit assertions that the Treasury will make up this shortfall are naive and complacent, given that successive governments have allowed Britain to languish well below the OEDC and EU averages in its research investment as a proportion of GDP.

“Science thrives on permeability of ideas and people, and flourishes in environments that pool intelligence, minimise barriers, and are open to free exchange and collaboration.

"The EU provides such an environment and scientists value it highly.”

More than 100 university vice chancellors also signed a separate open letter supporting Remain.

Question six, from maddiz, is: What would happen to already struggling people if we leave the EU and the cost of living goes up? Will we get extra help?

The short answer: This is the several-billion-dollar question. In the short term, almost everyone agrees the UK would take a hit. If that's particularly bad, the government might be forced to try to boost the economy and help the people hit hardest (if it can). In the long term, most economists agree the UK would be slightly poorer post-Brexit, but the Leave camp obviously disagrees.

The slightly longer answer: Whether leaving the EU would seriously damage the UK economy is one of the most bitterly fought questions of this referendum campaign.

Conservative minister and Leave campaigner Andrea Leadsom told BuzzFeed News: “My best expectation, with my 30 years of financial experience, is that there will not be an economic impact” even in the short term from Brexit.

In contrast, her former boss George Osborne said the UK would be hit hard in the short-term by Brexit, and even set out a swingeing "emergency Budget" that would fill a mooted £30 billion black hole with income tax hikes and cuts to the NHS, education, and defence.

To be blunt, neither claim is very credible.

Last week, when multiple polls showed a sustained lead for Brexit, UK stocks fell more than 5%, while the pound also fell (it has suffered throughout the referendum campaign).

Money talks, and it shows the expectation is very much that the UK economy would suffer in the short term after a Leave vote, especially given the uncertainty that would ensue in the weeks and months after the vote. This suggests Leadsom is very much in the minority when she suggests Brexit would have no economic impact.

However, that doesn't mean Osborne's terrifying emergency Budget is credible either. If the UK faced a crisis of confidence, the government would be very unlikely in the short term to raise taxes or cut spending, at least until things had stabilised. The Bank of England and European Central Bank have both indicated they would intervene if markets panic following the Leave vote.

However, in the longer term, if Brexit did hurt the UK economy, the government would eventually have to either raise taxes, cut spending, or both. The Treasury, World Bank, OECD, and International Monetary Fund have all said they believe Brexit would, in the long term, lead to a slightly smaller UK economy than a vote to Remain would.

And our final question comes from @Kayfourbee, who asks: How do we make it stop?

@jamesrbuk @BuzzFeed How do we make it stop?

The short answer: Voting takes place on Thursday 23 June. The votes should all be counted by fairly early on Friday morning. The referendum will all (finally) be over on Friday. The end is in sight.

The slightly longer answer: This might never end. Sorry.

If the vote is to leave, negotiations will take several years and will be bitterly divisive: Different models for how we would deal and trade with the EU would have different economic consequences and affect how much control the UK had over its borders. As a result, you could expect to see them regularly top the bulletins and front pages.

Additionally, it's widely expected Cameron would face pressure to stand down almost immediately in the event of a Leave vote, which, combined with predicted economic turmoil, would mean Brexit continuing to lead the news for weeks, if not months.

If the vote is remain, things might quieten down more quickly. As with the Scottish referendum, some fervent supporters may not accept the legitimacy of the result if it's close, or may feel a call for a second referendum is justified.

The questions here would not be so long-lasting as a Leave vote, but Cameron may still face a leadership challenge from furious pro-Brexit campaigns, and would also have to decide what to do with his cabinet if he survived any challenge – should he try to rehabilitate ministers who supported Leave or purge them to the back benches?

Whatever happens, there's really no immediate end to the Brexit debate in sight. Here's an apology puppy. Sorry.

Make sure to follow the BuzzFeed Community on Facebook and Twitter for your chance to be featured in similar BuzzFeed articles.

Questions have been lightly edited for clarity.