Brexit will force the government to borrow an extra £122 billion and slow down the UK economy for years to come, the UK's official economic forecasts have revealed.

Compared to the Budget in March, the UK's official forecasts now predict dramatically lower growth – 1.4% in 2017 vs a previous prediction of 2.2% – due to slowdown, higher inflation, extra government spending, and uncertainty, much of which has been attributed to Brexit.

The figures only take into account the early stages of Brexit, based on public statements by the government. The Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) – the independent government body responsible for the statistics – has warned there are numerous future risks not yet taken into account that could affect the figures still further.

The OBR said its report was based on the assumption that Brexit would reduce Britain's total potential output.

"We have made a judgment – consistent with most external studies – that over the time horizon of our forecast any likely Brexit outcome would lead to lower trade flows, lower investment and lower net inward migration than we would otherwise have seen, and hence lower potential output," it said.

Gross domestic product will be lower over the next few years.

The good news for the UK is that the OBR is not predicting a recession – but the economy is now expected to grow much more slowly than was previously predicted.

This means it will create fewer jobs, there will be less money for pay rises, and there will be less profit for companies – all of which hits the government's (and families') bottom line.

The OBR gives three main reasons for this slower growth. The first is that post-Brexit uncertainty will make companies delay or cancel big investment decisions.

The second is that the falling pound – which is down 15% against the dollar since 23 June – will push up prices, adding around 2% to inflation. Higher inflation makes customers spend less, causing a dip in GDP, the total value of all goods produced and services provided.

The third reason is that leaving the EU is expected to reduce net migration to the UK, partly due to new government policies and partly because the UK will be a relatively less attractive place for migrants to come. As immigration tends to boost the economy, this contributes to a dip in GDP.

The OBR is currently assuming Brexit-related uncertainty will be over by 2019, when the UK will – according to Theresa May's pledge to trigger Article 50 by March 2017 – have already left the EU. In practice, uncertainty over future trading arrangements or other causes could still have a big impact on the economy at this point.

The direct effects of Brexit will add £58.7 billion to government borrowing.

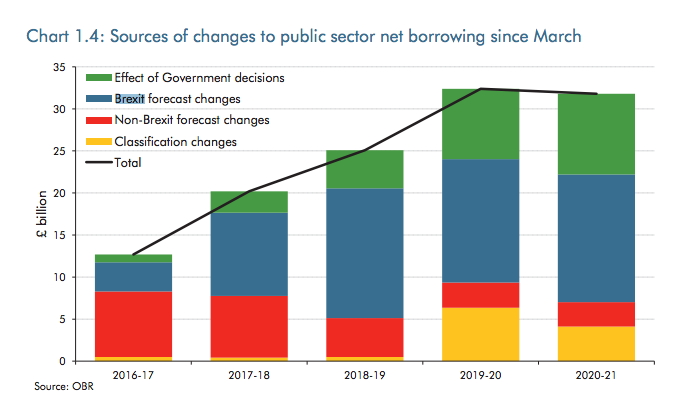

The above chart shows how the OBR predicts causes it attributes directly to Brexit will affect how much the government borrows each year, compared with its last forecasts made in March.

Most of the factors push borrowing higher – lower economic growth, productivity growth, and migration all mean there will be less tax for the government to collect, resulting in new cuts, tax rises, and/or higher borrowing.

The effect of lower migration alone is set to add an extra £16 billion of government borrowing over the period.

However, because the Bank of England is now expected to keep interest rates lower to boost the economy, debt repayments will stay cheaper, saving the government a relatively small amount of cash.

The OBR has assumed the UK will contribute nothing at all to the EU budget from 2019 onwards and will spend the money domestically instead.

There's an important point buried in this section of the report: While the OBR expects lower migration, its figures explicitly state it expects Theresa May's government to fail to reduce migration to "tens of thousands", as it has promised. If the government really did try to hit this target, it would increase borrowing still further.

Overall borrowing is going up by even more: Hammond is borrowing a total of £122 billion more than his predecessor, George Osborne, promised to in March.

George Osborne, when he was chancellor, set out three key fiscal rules he said would demonstrate the Conservatives' economic competence. In his first Autumn Statement, Hammond ripped them up.

Instead of promising the UK government would deliver a surplus by the end of this parliament, Hammond pushed back this goal to some time in the next parliament, meaning he can now keep on borrowing money.

The figures show he's planning to do just that. Some of the borrowing is the effect of the economic slowdown, but the breakdown of spending also shows that despite promising to make up for most of his new spending with tax rises, the chancellor is spending tens of billions of pounds more than Osborne – by delaying or cancelling some cuts and introducing some new spending.

The result is a low-key economic stimulus: It signals the chancellor is worried about the health of the UK economy and is trying to give it a boost without angering his pro-Brexit colleagues.

As to why the new chancellor has ripped up his predecessor's rules, one OBR graphic makes this clear: While Hammond would have failed to meet any of the old rules, he meets all three of the new ones he's written for himself.