The government has rejected proposals to introduce a new offence to tackle corporate crime in the UK, a ministerial answer has revealed.

In the wake of a series of global corporate scandals, from the collapse of Enron to the latest revelations about Volkswagen's falsification of emissions data, campaigners have been calling for more ways to hold corporations to account and examine whether some malpractice could be criminal.

But now ministers have decided that there is no need to introduce a new offence, because the fact that there have been no prosecutions under the Bribery Act shows that Britain does not have a corporate crime problem.

In the UK, prosecutions of large companies have been relatively rare as most offences relied on not only showing that conduct was criminal, but also that top executives at the company were directly aware of them.

The Bribery Act 2010 aimed to tackle that in the area of corrupt payments by making corporations liable if they didn't do enough to prevent low-level employees engaging in such activities.

But a government review published last year called for further action. The UK Anti-Corruption Plan noted:

In addition to bribery, there are likely to be other forms of economic crime for which it is appropriate to ensure that senior corporate actors are sufficiently accountable. The Government will therefore examine the case for a new offence of corporate failure to prevent economic crime and look at the rules on establishing corporate criminal liability more widely.

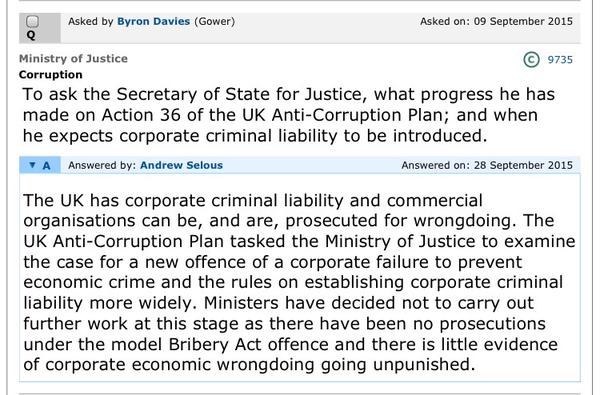

However, in a formal response to a question by Conservative MP Byron Davies, justice minister Andrew Selous said the lack of prosecutions showed "there is little evidence of corporate economic wrongdoing going unpunished", meaning no new laws were needed.

Campaigners have reacted furiously to the government's plans, accusing the government of "kowtowing" to corporate interests.

"In our experience, existing UK law is simply not equipped to tackle twenty-first century corporate crime," said Lucy Graham, Amnesty International's legal adviser on business and human rights.

"New rules specifically holding companies responsible for failing to prevent serious crimes in their operations would have been an important first step in addressing this imbalance.

"The government's latest climbdown instead suggests they are more interested in kowtowing to corporate power – despite an ever growing number of international corporate scandals from HSBC to Volkswagen and David Cameron's much-publicised commitment to tackling corruption.

"Multinationals benefit from massive global reach, with few rules holding them back from foul play. This has had devastating impacts on local communities. Until we have rules holding them to account, it will be one law for powerful companies, another for everyone else."

Amnesty has long challenged the UK on corporate accountability. Earlier this year, the organisation revealed UK authorities had admitted they lacked the "expertise" and resources to investigate Trafigura for its role in a 2006 toxic waste spill, despite the company having faced criminal prosecution in other jurisdictions.

The UK was also criticised for its response to revelations of the practices of HSBC's Swiss banking arm earlier this year, after 10 countries launched criminal investigations into the bank – but the UK took no such action.