Two Aboriginal men who were held in immigration detention will ask the High Court to find that Aboriginal non-citizens cannot be deported, in a case one expert describes as “landmark”.

In submissions filed with Australia’s highest court last week, lawyers for Daniel Love and Brendan Thoms argue that the government cannot deport an Aboriginal person who is not a citizen but has at least one Australian parent, came to Australia as a young child and has only left the country for short periods.

The lawyers say people with these characteristics cannot be considered “aliens” under the Australian Constitution.

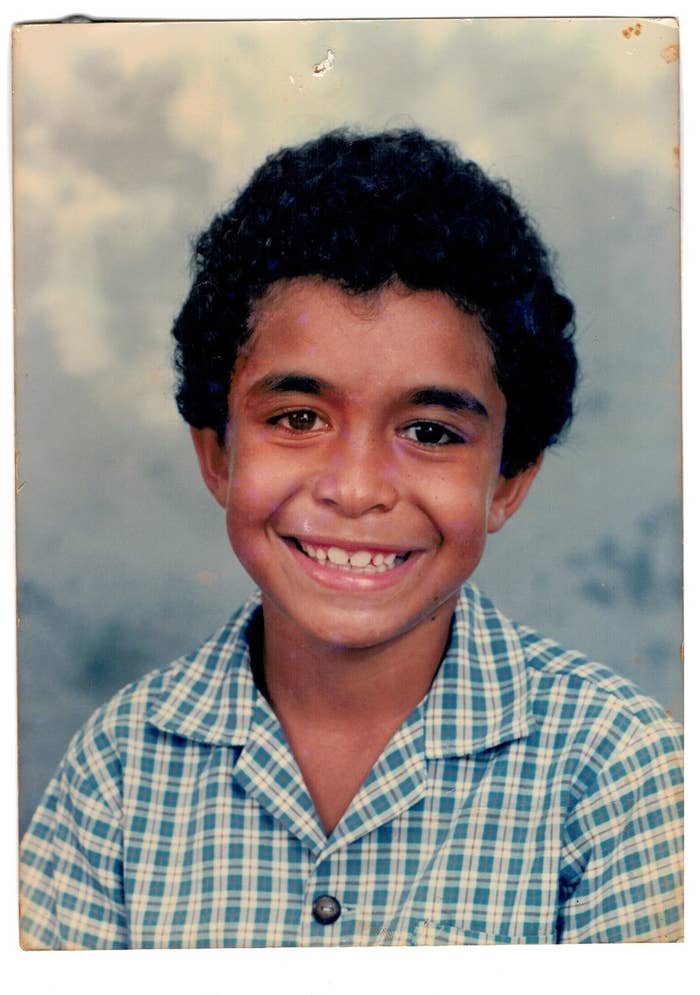

Love, 39, was born in Papua New Guinea to an Aboriginal Australian father and a Papua New Guinean mother. He moved to Australia at age five, and has only left once since then.

In 2018 a delegate of home affairs minister Peter Dutton cancelled Love’s permanent visa after he was charged with assault and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment. He spent seven weeks in immigration detention until a delegate reinstated his visa.

Thoms, 31, has been in immigration detention since Sept. 2018. He was born in New Zealand to an Australian mother and New Zealander father. Since moving to Australia at age six, he has gone overseas twice but not since he was 14. He was sent to prison and his visa was cancelled for a domestic violence assault.

Both identify, and are recognised, as Aboriginal: Love is a member of the Kamilaroi people, and Thoms is a member of the Gunggari people and also holds native title. Both are also fathers to Australian children.

The case will be a “landmark decision”, Sangeetha Pillai, a constitutional law academic and expert in Australian citizenship law, told BuzzFeed News.

“You’ve got two Aboriginal people who have lived in Australia the overwhelming majority of their lives but were born overseas and [so] don’t hold Australian citizenship,” Pillai said. “So the question the High Court has been asked to rule on is whether a person in that position is a member of the constitutional community in Australia despite not holding statutory citizenship.”

Harry Hobbs, an expert in public law and Indigenous rights at the University of Technology Sydney, agreed that the case could be “significant”.

If the court ruled in favour of Love and Thoms, “it would reflect (and continue) a profound shift in state approaches towards Aboriginal people,” Hobbs told BuzzFeed News. He said the constitution initially excluded Indigenous people from the political community in a number of ways. A victory for Love and Thoms “would recognise that Aboriginal people cannot be regarded as not belonging to and within the community,” he said.

It would come nearly 30 years after the High Court recognised in the Mabo case that Aboriginal people have special land rights stemming from their traditional laws and customs.

The High Court has never considered whether an Aboriginal person can be an alien, and we know “very little” about the boundaries in this area because there have been relatively few previous cases about citizenship and aliens, Pillai said.

“It will be a landmark decision that clarifies whether we have a constitutional community in Australia, and the boundaries of what aliens are constitutionally,” she said. “We haven’t had a big case in this area for 20 to 30 years.”

The submissions point out that Aboriginal people have been in Australia for tens of thousands of years.

“For descendants of Australia’s first peoples, an indelible part of the Australian community, to be ‘aliens’ for the purposes of Australia’s constitution, is antithetical to their indigeneity and to the social, democratic and political values which underpin and are protected by the constitution,” the plaintiffs say in their submissions. “The concept of Aboriginality is inconsistent with the concept of alienage.”

Pillai says the plaintiffs’ argument was not overly radical.

“In fact, the argument doesn’t seek to overturn any previous High Court decisions,” she said. The court has previously commented on what an alien is, but the lawyers say the definition did not consider people in Love and Thoms’ circumstances.

The submissions use the three-pronged definition of Aboriginality, which looks at self-identification, descent and community acceptance. This test has been used since the 1980s and is generally accepted by Indigenous peoples. Under the test, it does not matter where the person was born or if one of their parents is not Indigenous.

“An Aboriginal Australian person’s descent from other Aboriginal Australians, self-identification and community acceptance is so closely connected with being ‘Australian’ (as that concept is ordinarily understood) to take an Aboriginal Australian beyond the reach of the aliens power,” the submissions argue.

In Thoms’ case, the lawyers also say considering him an “alien” would mean the government could deprive him of the ability to use his native title rights.

If Thoms and Love win, they will be “non-alien, non-citizens”, a category the High Court has previously recognised for some non-citizens who are British subjects. A non-citizen, non-alien would not be able to vote, serve on a jury, or apply for certain public service jobs. But they also would not be able to be deported.

If they succeed, Thoms will be released from detention. Love is seeking $200,000 for false imprisonment.

It could also pave the way for other compensation claims, as a number of other Aboriginal people have been held in immigration detention.

The lack of previous cases make this one hard to predict. As well, the constitution does not give the judges a lot of text to interpret.

“You’ve got a text that is very sparse and was written a long time ago,” said Pillai. “It’s their job to work out the limits.

“It’s a situation where there’s an inescapable political dimension to it, and an inescapable moral dimension to it as well, and neither of those are territory that the court likes to actively advance into,” Pillai said. “But it’s looming in this case, it’s inescapable in the terrain.”

The case is likely to be heard next month.