Kangaroo Point Central Hotel & Apartments would look familiar to anyone who’s travelled on a budget. For AUD$95 per night, you can book a twin room in the L-shaped motel section of the complex, sandwiched between two nondescript apartment buildings, with an Italian restaurant by the reception.

The hotel complex is off Main St. in central Brisbane, a few blocks up from the KFC and McDonald’s. Walk five minutes west and you’ll reach the shores of the brown Brisbane River; the same distance south will land you at the Brisbane Cricket Ground, better known as The Gabba.

But it’s too hot and sticky — a classic Queensland summer — for that sort of thing when I arrive at Kangaroo Point Central. Besides, I’m not in Brisbane to sightsee, or go to a game. I’m here because I’ve heard the Australian government is detaining more than 80 refugees in this otherwise very ordinary hotel, and have come to see it for myself.

When I try to check in, on a Thursday afternoon in January, the receptionist struggles, saying the system is down because the hotel had lost power. I’m not surprised by this, as earlier that day a refugee advocate told me the air conditioning in the refugee common room had also broken down.

As the receptionist battles his computer, someone bursts in to inform the hotel manager that the “ops manager” has just told Serco — the private security company managing Australia’s immigration detention centres — that the air conditioning still isn’t working.

“There are 30 people in there,” the person says.

The refugees detained inside Kangaroo Point Central have changed the nature of the place. Proximity to tourist hotspots aside, the hotel is no longer just a hotel — it is also an APOD (“alternative place of detention”). It may not be a barbed wire facility, but it is a kind of detention centre all the same.

The dozens of men locked inside have already spent six or seven years trapped in Australia’s harsh immigration system. They are part of the cohort who sought asylum in Australia by boat, and were dumped in offshore detention centres on the tiny Pacific nation of Nauru, and on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island.

There, many were found to be refugees, but Australia still refuses to resettle them, and their health has deteriorated after years in limbo. Hundreds are still there, but hundreds more have been flown to Australia, in need of urgent medical care. Some of those people ended up at Kangaroo Point Central. Now, instead of their prison being an island, it is a city hotel.

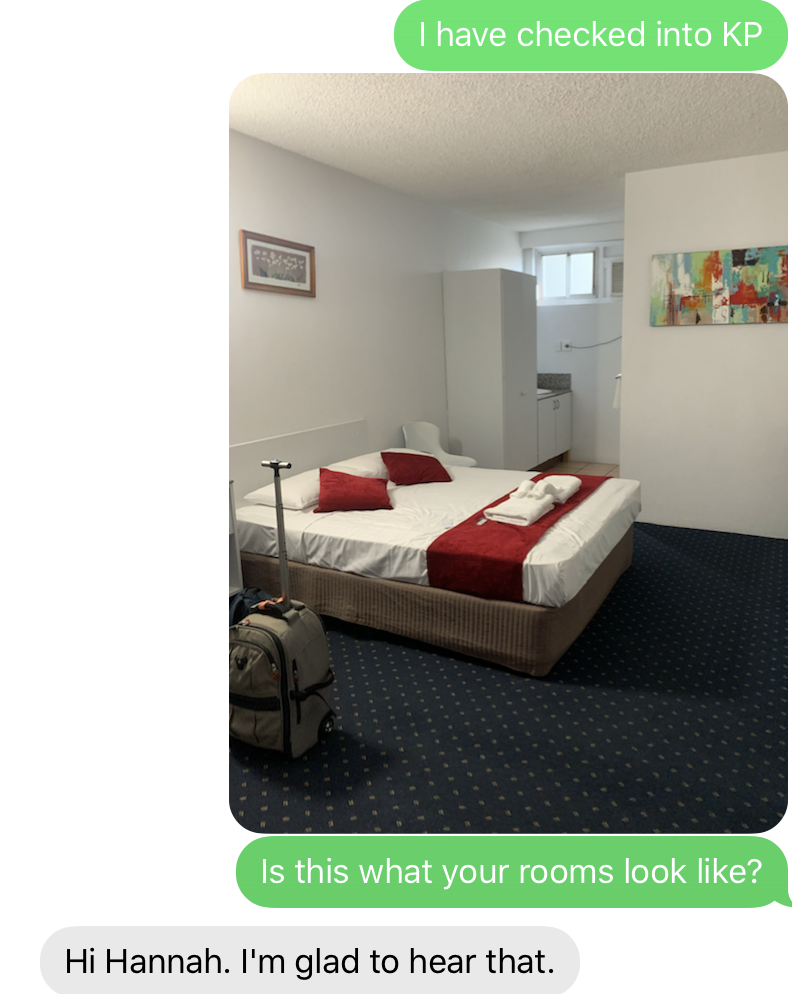

After I finally check in, I am shown to Room 5 on the motel’s ground floor. En route, I catch a quick glimpse of burly men in polo shirts outside the entrance to Walmsley, one of the serviced apartment blocks. The men are sitting in a row, eyes are fixed on their phones. They are clearly guards.

I plan to visit a refugee living in the hotel, H, but can only go to his room at a pre-arranged time on Friday afternoon. H, who is in his 20s, asked not to be identified in this story, to protect his safety and that of his family in the country he fled.

Immigration detention is not meant to be punitive, and detainees are allowed to have phones, so I text H to find out exactly where in the hotel complex the men are being held.

I haven’t figured out the lay of the land yet, and I ask H to send me a picture of the view from his window so I know where the men are held. From his photo, I can tell H is in the apartment building facing Lockerbie Street, the Lockerbie Apartments. On arrival, Google Maps had taken me into the Lockerbie’s ground level car park, but each spot was either full or reserved, and a tall man in a dark polo shirt quickly directed me to another entrance and car park off Main St.

Later, I learn that Lockerbie is home to the administrative hub of the APOD, and that its car park is where men being taken to the city’s detention centre, or to medical appointments, get into cars, hidden from public view.

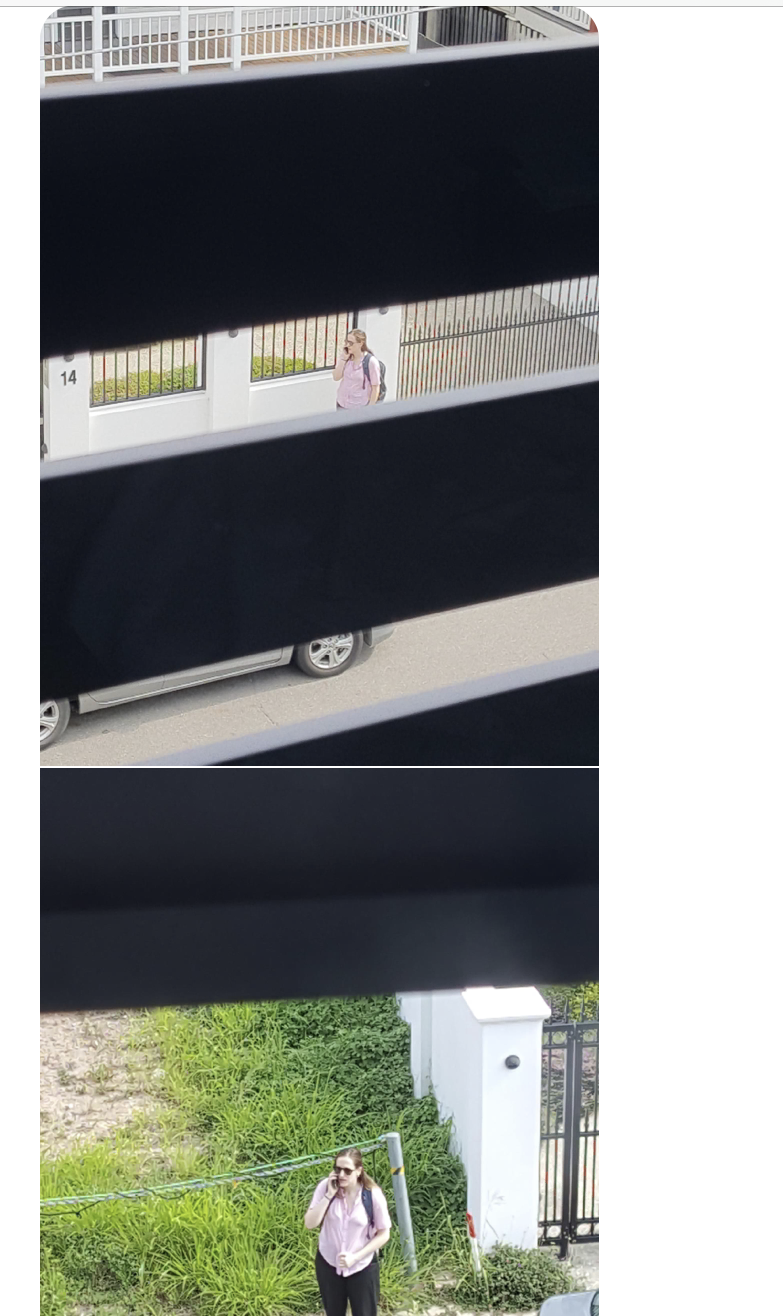

I walk along the street opposite the building, trying to spot and wave to H in his room, but I can’t see him. Security bars cover the windows and balconies (Google Street View shows they have been there since at least 2013). He can see me, though, and sends through a photo.

It’s the end of the school day, and families are walking their kids home from the primary school up the road. Every few minutes, a people mover enters or exits the driveway — the same burly white guys in polo shirts driving, and asylum seekers or refugees in the back.

That evening, I overhear a hotel staff member showing a woman around the motel rooms. No, she can’t stay in a serviced apartment, he tells her: all of them have been booked long-term by a private company.

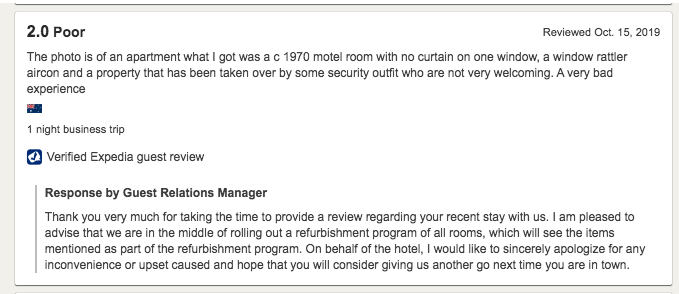

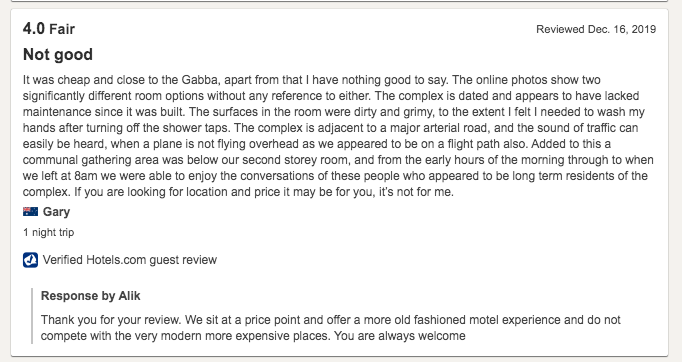

The odd arrangement at Kangaroo Point Central is annoying at least some of its guests, according to online reviews. One person wrote on Expedia in October that the property “has been taken over by some security outfit who are not very welcoming”. Another, posted on Hotels.com in December, complained of loud conversations from the “early hours of the morning through to when we left at 8am” — and I wonder if they too had been awoken by the row of guards sitting outside the Walmsley.

Other guests have complained that they booked a serviced apartment, only to show up and be told they were all full, and they now had to stay in a motel room.

As I sit at a cafe across the road on Friday morning, guards occasionally walk in and out, buying a takeaway coffee or water before heading back across the street. They enter and exit via the Walmsley Road entrance, which is blocked off by two rows of cars.

Once the cafe is clear, I ask the woman manning the till if she knows refugees are being detained at the hotel. “Yes, we know,” she nods. She’s unfussed by the whole thing. “It’s a separate building,” she says.

“Isn’t it weird?” I say. “A hotel full of refugees?”

“We don’t see them,” she replies. “It’s fine, it’s happening everywhere.”

She might be referring to the Mantra Bell hotel in Melbourne’s Preston, which is also serving as a makeshift detention centre for refugees who have been flown to Australia for medical treatment.

Australia’s Human Rights Commission recently warned against using hotels as APODs, saying in a 2019 report they are “not appropriate” places of detention due to a lack of dedicated facilities and restrictions on open space.

“Accordingly, hotels should only be used as APODs in exceptional circumstances and for very short periods of time,” the report said.

H has been in Kangaroo Point Central for four months, after first being held for a month at the Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation (BITA). Multiple sources told BuzzFeed News that at least one man has been held in the hotel for more than a year.

So, why is this happening? Nobody will tell me. I sent detailed questions to the Department of Home Affairs for this story, but heard nothing back, which is not unusual. Among those working in the field, there are competing theories. Some think the hotels contain the more vulnerable men, whose poor mental health demands a closer eye. But as the Australian Human Rights Commission has pointed out, those at risk of self-harm are usually held in a hospital. Others think it could be capacity issues at the detention centres, or economic concerns. Others still think they're the men who are quieter and less trouble.

But nobody knows for sure. The people who are most affected — those locked inside — do not know either. The men I have spoken to locked in hotels say they have asked, but have not received answers. They say there’s no pattern to the people chosen to go to the hotels, apart from that they’re mainly single men.

At 3.15pm on Friday it’s time for my visit with H. To get in to see him I had to book a week in advance and provide 100 points of ID. I return to the Lockerbie driveway, but this time head towards the sliding doors of the small lobby.

Inside, a woman is at a makeshift reception set up on hotel furniture: a large wicker chair and matching table, with a glass top. After I’ve signed in, passed a mobile metal detector test, had my ID checked, left my bag with the guards and put on the fluoro vest I’m required to wear, I sit and wait. The space is cramped, and a large pedestal fan is the only thing keeping us cool.

I spot a well-highlighted piece of paper stuck to the wall, advising staff on what to do if the media turns up: “Remain calm and be polite. Do not make any unauthorised comment. Do not block the camera with your hand.”

I wait for 10 minutes before guards advise H is ready to see me. I’m escorted into the elevator by a guard and we ride from G to the top floor, Level 4. Walking to the visitor’s room, we pass guards sitting on a balcony off the hallway, with a large pile of Men’s Health magazines and sandwich bags filled with nuts on the table in front of them. A poster on the wall, with a Jim Carrey meme, advises men how they can get a haircut.

I meet H in the visitor’s room. As he fixes me a styrofoam cup of tea in the kitchenette, I look around. It’s a worn apartment that’s been converted into a kind of activity room for the men who are held under guard in the hotel. There’s a TV, a Yahtzee box, a few computers, a daggy mirror, shabby furniture and kitsch art on the wall.

The curtains are drawn and it’s dark in the room. A young guy and an older woman with walkie-talkies are the only other people in there. When I use the bathroom, I see the shower cavity is stacked full of boxes of tissues and styrofoam cups.

H has been in the hotel since October, after he was brought to Australia from PNG because of physical and mental health problems, then spent a month in the Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation (BITA). In a soft voice, he tells me about life in the hotel.

The men usually sleep two to an apartment: one in the bedroom, one in the living room. Their doors don’t lock, and guards regularly enter their rooms without knocking.

Opportunities for fresh air are severely limited. The men cannot open windows, and although the rooms have balconies, the doors to them are locked. There is one small outside area — near the pool, which they aren’t allowed to use (though neither are regular guests, at the moment) — where they can go to smoke.

The only other way to go outside is to sign up, at least a day in advance, for a trip to BITA — an actual detention centre — a 20-minute drive away. But to do that, the men must be subjected to four pat searches: when they leave, arrive, leave, arrive. And although people held in BITA have more freedom to walk around and play sport, H is no fan of the centre.

“We’re done with fences,” he says.

During his time in PNG, H suffered from flashbacks to violence he experienced in his home country. His doctor told him they wouldn’t come so often if he went somewhere he felt safe and secure. Kangaroo Point Central is not that place. “This place is 100% not helping me,” he says.

Since his arrival, H has had one appointment with a psychiatrist at BITA. He was prescribed medication. Back in PNG, he had counselling from the NGO sub-contractor Overseas Services to Survivors of Torture and Trauma (OSSTT), which he says helped. But at Kangaroo Point, he hasn’t been given access to counselling.

H was proactive: he called OSSTT and told them of his situation, and they agreed to give him weekly telephone sessions. It’s helpful, but not the same as talking to a person sitting in front of him.

He says the men mainly spend their days in their rooms, looking at their phones. There are activities provided, including English and history classes. H is eager to stress that the guards are friendly, and he’s not treated badly.

“We don’t have any problem with the government. We don’t have any problem with the Serco people here,” he says. “We only want to get out of detention and this hotel.”

H fears being sent back to BITA, which he believes would be even worse for his mental health. But he chose to speak out about his life because he wants people to know what is happening in this hotel.

“There’s no reason to keep us here,” he says. “They’re wasting more money on food, guards and accommodation. If we were outside we would help ourselves.”

His ambition is modest: community detention. That means placement in residential accommodation, without work rights but with a curfew.

“We do not want a lot, all we want is to live like all other normal human beings and not live like detainees anymore,” H says. “There are a lot of skilful people among us who could happily contribute to the Aussie community if given a chance.”

To get into community detention, he needs the home affairs minister, immigration minister or assistant home affairs minister to personally intervene. At the end of August, the average number of days between transfer to Australia and release from a detention centre or APOD was 161 days. That’s about how long H has been detained in Australia.

“I want to get freedom, anywhere that’s possible,” he says. “We have spent a lot of time in detention. We do not want to spend any more time in detention. Brisbane is a big city, they could just settle us out there. Maybe in the countryside somewhere. As long as it’s not in the hotel.”

The staff at Kangaroo Point Central get jittery and fall silent when I ask about the refugees in the serviced apartments. Everyone at the hotel acts like what’s going on is a secret — but it’s not a particularly well-kept one.

“I’m under strict confidentiality on that,” says the receptionist as I check out. When I ask how long it’s been going on, he doesn’t reply.

I call the hotel manager and he too can’t talk. “Number one, I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he says.

He then blames company policy: “Unfortunately, as with any inquiry about any guest and any circumstance, we cannot divulge any information whatsoever,” he says. He specifies that his company “just provides a management service, we don’t do anything beyond that”.

As I take some last minute snaps of the building, I am approached by a woman who asks me if I’m taking photos of the hotel and, if so, why, and who I work for.

I tell her I’m a journalist with BuzzFeed News. She wants to know why I’m interested in the hotel. I tell her I’m looking into its use as an APOD to hold refugees.

“Who told you about that?” she demands to know. I ask who she works for, and she says the hotel. She starts a new sentence with “You do realise…”, then stops and walks away.

After an hour with H it’s time for me to leave the visitors’ room and the hotel, and fly back to Sydney. As I head home he sends me some more thoughts via WhatsApp from his hotel room.

He doesn’t know what his future holds, and he hasn’t known for over six years. Like hundreds of others in the same situation, he has no visa to stay in Australia. The government’s official line remains that H and his peers will ultimately be sent back to Nauru and PNG.

He describes his years in detention on Manus Island as an “unforgiving situation” that a human being could “barely put up with”. He held some hope about being transferred to Australia, but being confined in a hotel in central Brisbane has brought new, acute feelings of sadness.

Like this, on trips to BITA: “Instead of helping, it only makes us feel that we’re in a detention centre and we’re detainees. On our way to BITA, we see beautiful parks and places, but we have no access to that at all.”

Confined to Kangaroo Point Central, he is reduced to watching the world pass him by.

“I even envy the dogs,” he said. “Their owners take them out for a walk. They’re living like normal.” ●