“I remember when I got the knock on the door from West Yorkshire police that morning, my first words were ‘I'm not surprised,’” Nick Castree said, recalling the moment that he was told his father had been arrested on suspicion of sexually assaulting and murdering a little girl three decades before.

Nick, 27 at the time, had returned from working a night shift at a care home, and his husband, a police officer, had also been on nights. The pair had been in bed for only a couple of hours when they awoke to the sound of the intercom to their apartment buzzing.

“They called at all our houses – my mum, my brother,” Nick said. “We all got the same call at the same time. I went to bed an innocent young man and I woke up the son of a murderer.”

Nick remembers his father, Ronald Castree, as an aggressive tyrant who made life in their family home in Oldham, Greater Manchester, very difficult. “I knew he was a dangerous man, but I just hoped he wasn't that dangerous,” he said.

Nick says childhood was difficult, but he got on well with his brothers, Jason, who is four years older, and Daniel, who is five years younger. His father had a well-paid job in accounting and drove a taxi at night, and the family lived in a nice house with a garden. But Ronald refused to spend any money on his children, who Nick believes he thought of as “leeches” and “a drain” on him.

Nick said the children were known to social services, and his father would beat Jason and his mother Beverley and was psychologically abusive to the whole family.

“It was absolutely horrendous,” Nick said. “We had no love whatsoever from either parent. My mum couldn't show us love because she was too badly psychologically scarred by my father.

“I hated school. I was bullied because I had poor clothes, hand-me-downs, and then I started being bullied for my sexuality. But I absolutely idolised my older brother – he'd let me sit on his motorbike, and I would look up to him."

Ronald convinced Beverley to give up her job as a telephonist to stay at home with the children – which left her completely dependent on her abusive husband.

“I knew he was a dangerous man. He physically attacked my older brother, beat him black and blue throughout my childhood. There was emotional, psychological abuse of me.

“My father was like a powder keg, waiting to go off. We were always waiting for the next explosion. The only happy times were on holiday, when we were away from the family home.

“We'd come in from school and if we made the slightest bit of noise he would tell us to eff off out the room. He'd throw meals at the wall, put his fist through the wall, he was a bully. He'd go on a drunken rampage when he'd drunk a bottle of whisky a night.”

Nick said he was bullied by his father from a young age, explaining that Ronald would make homophobic comments like “You'll never amount to anything, you're queer” and “You're a jumped-up fairy.”

“I didn't know what that meant back then,“ Nick said. “I would think, Why doesn't he love me?, and my mother would say ‘Just stay in your room.’ I lay under the duvet just wishing to die rather than live another day with my parents’ dysfunctional relationship.”

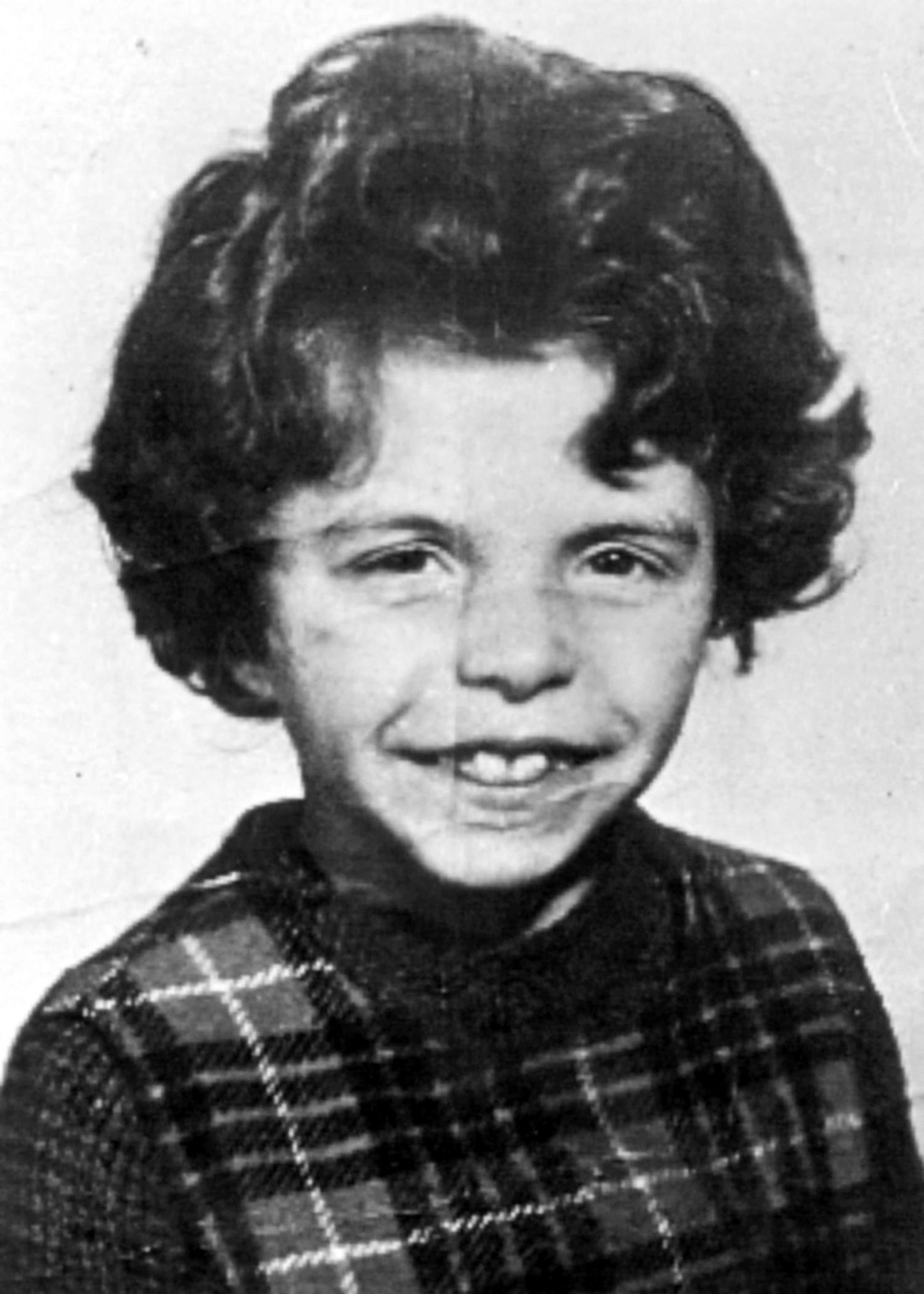

But although Nick knew that his father was a violent and dangerous man, he did not know exactly what he was capable of until he was 28 years old. For more than 30 years, Ronald Castree had kept a dreadful secret. In 1975, four years before Nick was born, he had killed a little girl, Lesley Molseed – and stood by as another man was sent to jail for her murder.

Ronald was on his way to visit his wife and newborn son – Nick's elder brother – in hospital when he abducted 11-year-old Lesley from a street near her home and took her to a West Yorkshire moor, where he sexually assaulted her and stabbed her to death.

Lesley, known as Lel to her older brother and sisters, was small for her age and had learning difficulties. She had gone out to the shop to buy bread for her mother when Ronald Castree snatched her off the street.

When the girl failed to return home, her family reported her missing and spent several anguished days waiting for news. The local community was shaken, and neighbours organised search parties to look for Lesley, while her face was all over the national news – in the papers and on the television.

The 11-year-old's body was found three days later, in a lay-by on moorland, by a passing motorist. Lesley had been sexually assaulted and stabbed in a frenzied and brutal attack, which left her with a dozen wounds on her head, shoulders, and back. One of the stab wounds had penetrated her heart.

Police soon pointed the finger at local misfit Stefan Kiszko, a tax clerk with a learning disability who lived near the girl's home. He was charged with Lesley's murder on Christmas Eve and convicted in July 1976.

Kiszko spent 16 years in prison, while Ronald Castree remained a free man.

Nick says he was familiar with the story of Lesley's murder growing up, as his auntie lived on the same estate in Rochdale, called Turf Hill, as Stefan Kiszko and Lesley Molseed.

“We used to watch Crimewatch UK,” he said. “I remember very well we'd occasionally bring it up in the family home about Stefan, and my father told us to ‘shut up and stop watching that crap’.”

But less than a year after murdering Lesley, Castree was convicted of abducting another young local girl and trying to assault her in an empty house – but as it was classed as a first offence he was only fined and served no time in prison.

He inherited a substantial sum of money from his father and started selling comics from a market stall, later running his own comic book shop. He even posed for a national newspaper, wearing a Batman baseball cap, and told a reporter at the time: “The timeless appeal of the comic is escapism. As people increasingly need a break from real life it can only mean greater popularity for comics of all kinds.”

After a long campaign from Kiszko's mother, Charlotte Kiszko, for his release, he was finally cleared of any wrongdoing. He said police had bullied him into making a false confession, and a group of teenage girls admitted they had lied when they told officers investigating Lesley's murder that Kiszko had exposed himself to them.

The investigation into Lesley's killing was opened up again in 1991.

Kiszko was exonerated, but while he was in jail his mental and physical health deteriorated and he developed schizophrenia inside. He died from a massive heart attack a year after his release – before he could receive the payout he was awarded for his wrongful conviction. His mother, Kiszko's only living relative, who had campaigned tirelessly to free him, died just four months later, meaning the government never had to pay out any compensation.

After Kiszko was freed, police put out fresh public appeals in a bid to catch the real killer.

In his late teens, Nick eventually managed to cut ties with his father. “I encouraged my mother to leave my father in 1997. I set up home for her,” he said. He had left school at 16 and gone straight into full-time work, and unbeknownst to his father, by the age of 17, he had managed to rent a home and take in his mother and younger brother.

“We packed her what we could behind my father's back,” Nick said. “I rented a house behind my father's back. We literally flitted away, just loaded up my car with what I could carry. My older brother came back [while we were packing] and we begged him not to tell my father, and he didn't. I knew what I was taking on: I was caring for my mum and my younger brother.”

The family moved within the same town, and managed to evade Ronald for a few months. He eventually tracked them down and begged Beverley to come back, but she refused. Nick hasn't seen his father again since then – except in court.

Nearly a decade later, in 2006, Ronald Castree was arrested and charged with Lesley's murder, and Nick received his knock on the door.

Ronald had originally been arrested on suspicion of raping a sex worker in 2005, and although the charges in that case were dropped, advances in DNA technology meant that a year later police were finally able to link him to the killing.

And it wasn't just Ronald Castree's secret that came out when he was arrested. Nick's mother, Beverley, had to sit down ahead of the trial and tell her sons that Nick's older brother was actually his half-brother, conceived by another man.

This, he thinks, is the reason why his father would only beat Jason, and not his other two sons.

“I was the middle of three boys. We thought we were three brothers,” Nick said. “My mother disclosed he was our half-brother. She had to tell us before it came out in the trial. My mother knew, my father knew, my grandparents knew. They kept it a secret.”

Nick said the revelation meant that certain things from his childhood began to slot into place. “My mother's mother hated me and my [younger] brother. She idolised my older brother – it was because he wasn't my father's. My grandmother hated my father with a vengeance. It all made sense.”

“There's been too many secrets in my family,” Nick said, explaining that his relationship with his mother is still strained.

“How many more secrets had my parents been holding from us? And why were they only telling us now? I walked out of the house in disgust. I'd always been close to my mother growing up, but it had always been a lie.

“I'd like to report that we are happy, but that isn't the case; they [his other family members] are still victims of my father.”

It took almost a year for the case to come to trial. “My life was on absolute hold,” Nick said. “Everything had been a lie, and I was just a complete zombie, an absolute wreck. It was horrendous, the worst year of my life. I'd walk down the street and think everyone was talking about me.”

When the trial started, Nick went to court every day – except for the days when his mother was giving evidence, as he was not allowed to be there. (He was initially listed as a witness for the prosecution so was not allowed to hear the evidence of other witnesses, but in the end he was not called.) By now, it was 2007, and it had been 10 years since Nick had last seen or spoken to his abusive father.

“I went to court every day, from the moment I was allowed into the courtroom. I went every day and sat in the second row back, me and my family. Lesley Molseed's family were in the first row,” he said.

“I hoped and prayed my father would look me in the eye. I hadn't seen him since 1997. But he wouldn't look in our direction.”

In court, he heard evidence being given against his father. “Every day it was just like another layer was being taken off me, peeling everything back,” Nick said. “By the end of the trial I was just a core, a red raw core.”

Nick said the hardest moment for him was when his father was finally convicted of murdering Lesley. Ronald Castree was sentenced to life in prison for the crime. He was told he would not be eligible for parole for 30 years, by which time he would be 84 years old. The judge told him that he was likely to die in prison.

Nick said: “When the jury had found him 10–2 guilty, that he did abduct that little girl, take her to moorland, sexually assault her, stab her, then went back to his family and his newborn child, that's when it kicked in. I just broke down.

“My whole life had been a lie. Lesley's sister had said to me [during the trial] ‘Our nightmare is coming to an end; yours is just beginning,’ and I didn't know what she meant by that, but then I did.

“They took him down and the door slammed shut and I thought, I'm the son of a murderer, I'm his firstborn. The feeling was horrendous. Would I be judged? Was I like him? It took me years to realise that I wasn't like him.”

Nick said he kept in contact with Lesley's family for a while, they exchanged telephone numbers and email addresses, and the Molseeds invited him and his family to attend a tree-planting ceremony in Lesley's memory. “It did go on for a little while, we helped each other,” he said.

But it was not just his father's crime that Nick had to deal with. He also had to come to terms with the fact that his father had allowed an innocent man to rot in jail.

“For my father to allow an innocent man to serve 16 years, develop mental health issues, I can't forgive him. It's absolutely disgusting. It's absolutely disgusting that he allowed that to happen.”

He also discovered that his father had abused other children. “My father was a serial paedophile,” he said. “When I was told he had sexually assaulted boys I felt disgusted. We always thought we were safe because he was interested in girls, but now any father-son bath time, rough-and-tumble, was he getting kicks out of it?"

Nick has had to address further family abuse that happened in his early teens, when he was abused by his paternal grandfather for several years.

“My father's father was a convicted paedophile,” he said. “He was convicted of indecency in a public toilet with a minor, and he molested me. I was 13 or 14 and it continued until I found him dead.

“I had left school 12 months before and was caring for him in his bungalow and I went in one day and found him dead, naked in his bedroom. I phoned my mother and she let my father know. That image will never go away, and that's how I knew the abuse had ended. He was dead and couldn't harm me any more. I'll never forget that day – my dad standing over his father's body, and I thought, If you only knew.”

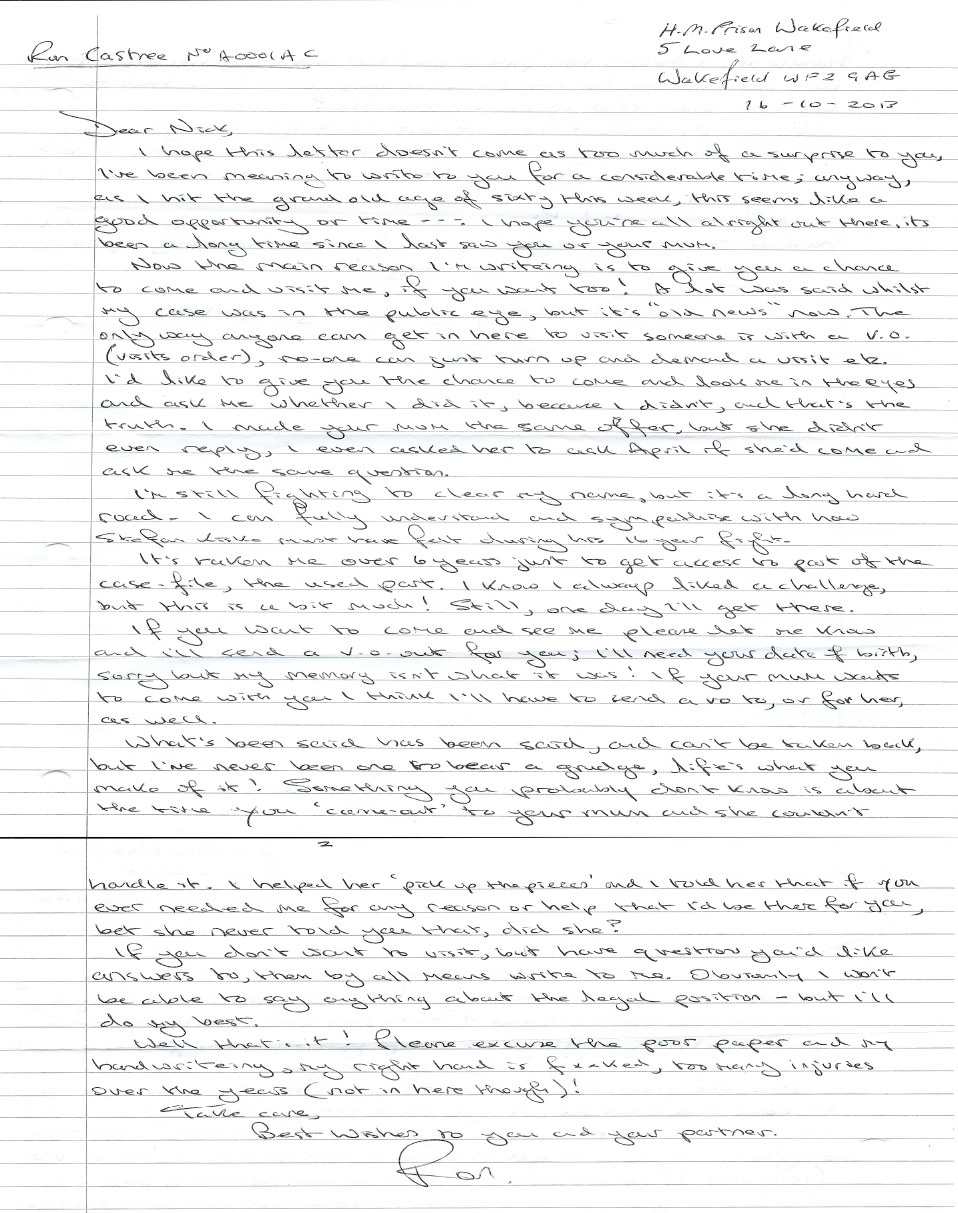

The last time Nick heard from his father was four years ago, when Ronald wrote to him from prison.

In the letter, he asked his son to visit him, and also protested his innocence, saying: “I'm still fighting to clear my name, but it's a long, hard road. I can fully understand and sympathise with how Stefan Kiszko must have felt during his 16-year fight.”

Nick did not accept his father's invitation to visit, and did not write back. “The only time I ever tried to contact him was in the first 18 months of his conviction,” he said. “I wanted to know why he treated me so badly during my childhood.

“I wouldn't want to discuss Lesley with him because I believe he's convinced himself after 30 years that he hasn't done it, so when I received the letter I did nothing but put it in a drawer; also I couldn't have anything to do with him anyway, as that's when I began looking to adopt and I can't have anything to do with a criminal.”

Now Nick has his own family and runs a successful property management business. Only three months before the police came to his door, he had made his relationship with his partner Anthony official in a civil partnership – the pair are now married and have a son together – but his greatest fear at the time was that his husband would leave him.

“We were still in the honeymoon period,“ he said. “I thought he would walk away. I had to deal with a lot of stuff I'd chosen to bury, and hoped it would go away, but he stayed with me through it all.”

With Anthony's help, Nick had counselling, which helped him to deal with the thoughts and emotions he had bottled up for years. “It was years and years of counselling,” he said, “from just before the trial, during, and after. Things like that don't go away, but through years of counselling it does help. It's the mental scars that nobody can see that take years to heal.”

And now, 10 years on, Nick has written a book that tells his story, which has helped him move forward. “Being able to have the book out, it's closing the chapter for me,” he said. “Now I want to move on and be a family with my son. I won't be a victim. It's because of what I've been through that I am who I am.

“I'm a survivor. I won't be a victim of my father any longer.”