BuzzFeed News has reporters across five continents bringing you trustworthy stories about the impact of the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

“I can't think of anybody else who's ever lived through a Ramadan like this. Certainly I can't remember anything in my life and my parents can't remember anything in their life, anything like this,” Faraz Ali told BuzzFeed News.

Ali is a dermatologist who has been redeployed to the front line after dermatology services — with the exception of urgent cases such as melanomas — were suspended. Instead of working his normal routine hours, which were much closer to a 9-to-5 job, he is now working 12- to 13-hour shifts several days in a row and switching frequently between days and nights.

So far, he has been working night shifts so fasting has not been too challenging, but he said there are a few things that make this Ramadan harder for healthcare workers.

For Muslims this year, the month looks very different. It is a time of spirituality but also a time of community — it is not just about fasting, but is usually also a chance for people to spend time at the mosque, and to connect with family, friends, and neighbours.

With places of worship closed, and everyone restricted to their homes, Ramadan in 2020 has changed. And for Muslim healthcare workers, their job looks different too — while they may be used to fasting at work, shifts can now be longer, and personal protective equipment (PPE) makes them more gruelling.

Some NHS staff have temporarily moved out of their family homes in order to protect vulnerable relatives, and as the coronavirus crisis continues into Ramadan, what should be the most sociable month of the year has instead become a very lonely time. Rather than joining family and friends for the evening iftar meal and predawn suhur meal, they are eating takeaways alone.

Guidance from the British Islamic Medical Association says the COVID-19 pandemic is an “unprecedented situation” and “abstaining from fasting may well be a sensible and pragmatic option” for medics working long shifts and wearing heavy PPE — a view that has been supported by some Islamic scholars. The British Board of Scholars and Imams (BBSI) has said that if medical staff struggle to adapt to fasting on shift, they can refrain from fasting while at work.

And with all annual leave cancelled, some Muslim healthcare workers will be also be spending Eid al-Fitr — the religious holiday that marks the end of Ramadan — at work.

“From a Ramadan point of view, when I was training as a junior doctor we did long shifts, so I'm quite used to fasting when doing long shifts,” Ali said. “But now, it's a little bit more different because the whole circumstances changed in the sense that we're doing these long shifts long-term now, but also we're shifting from day to night pretty quick, and that’s a little tough really.”

“Then the other added component is of course the PPE,” he added. “The PPE is not something you can leave on all day. The way we've been working is we put on the PPE and then we'd be in the COVID areas for a few hours at a time and then have a break, because actually having the mask on and having the apron on and the full gear, etc, it can be quite demanding on the body.

“People don’t quite realise, the physical aspect of it is a little bit more draining. You're constantly breathing into a mask, which is not very comfortable.”

While so far he has been able to fast every day, Ali said he is open to the idea of not fasting should he need to and has welcomed the support and guidance provided by Islamic community leaders on this.

He said: “It's a good thing that a lot of the Muslim leaders and the imams, they’ve said that it’s absolutely fine to not fast, if you are particularly on the front lines, and it's getting difficult and if you do need to, you can drink. So I'm very much open to that — if I need to do that, I will.”

While he is still on nights right now, he can fast, but he said he may have to take days off when he is working day shifts.

“If that turns out to be quite hectic and quite challenging then yeah, absolutely I'll consider not fasting,” he said, “because I'm a strong believer that safety and healthcare of patients comes first. So if that is compromised in any way, then it is advisable not to fast.”

Ramadan is not just about fasting — it is time to come together with family, friends, and the wider community; to develop spiritually; and to devote time to charity projects. Many Muslims look forward to the month of Ramadan — including the fasting — all year round.

“It's quite festive,” Ali said. "We get together regularly in the evening, break our fast together, either in the mosques or sometimes we even go out together, as families and friends, and then we have the night prayers in the mosques, but of course, all of that is shut down.

“So I think what people are struggling with is the spiritual aspect and trying to try to make it feel like it's Ramadan, because Ramadan is more than just eating, drinking. It's everything that surrounds it: the worship, the spiritual aspects, the community, the charity work, the charity events. So all of that now is just shifted completely online.”

Ali said he is the only person on his team fasting, and while his colleagues have been very supportive, breaking your fast alone can be lonely.

“I will always find that fasting when you're working can be a bit of a lonely experience,” he said, “because you sort of breaking your fast by yourself.”

However, he said for others, every iftar is lonely, even when they are not on shift, because they are temporarily living alone.

“A lot of doctors have actually moved out,” he said. “They're living in accommodation by themselves and hotels and flats and whatnot, because they have vulnerable people at home.

“So I've seen, I've heard a lot of experiences where people are feeling that real lonely effect of breaking fast at home and just getting takeaways and then just going back to work and dealing with the psychological aspect of COVID patients.”

Ali was living in an extended family setup and did consider moving out to live alone, but instead moved out with his wife and children, as his parents are in a vulnerable group, and he did not want to put them at risk.

When Eid comes around — unless lockdown restrictions are eased — it will be just him and his wife and the kids at home. There will be cake and presents and new clothes, so it still feels special.

“We'll still try and make it feel like Eid,” he said. “At the very least, we'll still try and decorate our house, have presents, have a big feast or something like that, we can't go anywhere else, other than the back garden, so we’ll just have to enjoy that.”

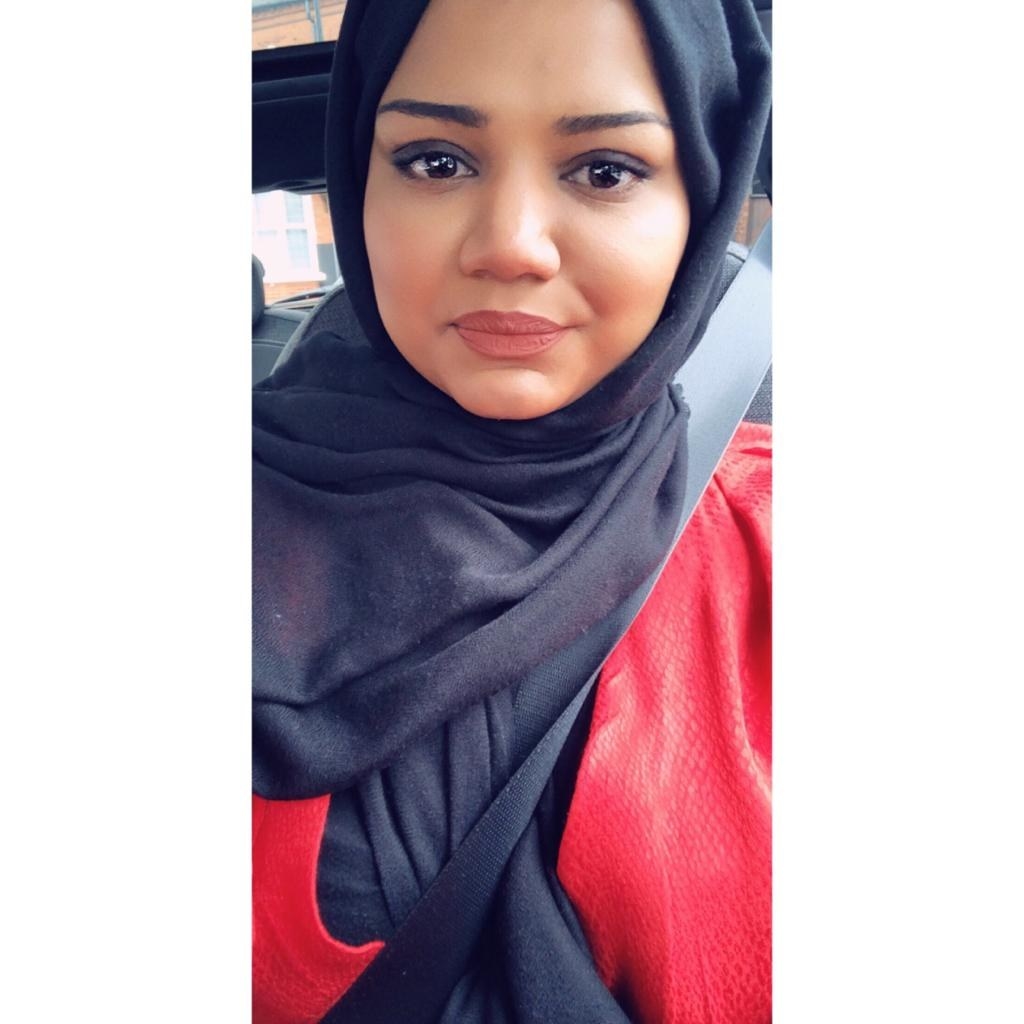

Kiran Rahim is a pediatrician who is currently working shifts in adult intensive care to help with the COVID-19 effort.

While working long shifts on coronavirus wards is difficult, she said what is harder is missing out on the community spirit of Ramadan that Muslims look forward to every year.

“We gather in mosques in our homes, and it's not uncommon to have massive iftar feasts,” she said. “So have multiple generations in the family eating together, for the evening meal and again for the dawn meal.

“And that is the biggest change, that loss of community, which I think we've all felt, irrespective of whether we're celebrating Ramadan or not, that is particularly poignant now.”

“I've tried to make it more special for my boys,” Rahim said. “I've really tried to decorate my home and try and get that Ramadan feel at home. I’ve made a little mosque for them — it's not really a mosque; it's just an area that we pray in to build that community spirit that we normally have.”

Working on the front line during the current pandemic is also not without its challenges, and Rahim said she has been unable to fast on her days on the COVID-19 wards.

“It is really difficult with the PPE. It's very uncomfortable,” she said. “It's very dehydrating, and you maybe two, three hours with that, before you have to come out and wash your face, take a drink.

“I'm a pediatric registrar by background. So before I was in adult ICU, I worked with kids, so I'm used to busy shifts, and I'm used to working 13, 14, 15 hours and fasting. The PPE is a whole other level of strain on the body.”

While she said support from the wider Muslim community has been helpful, she said so too has support within the hospital from non-Muslim NHS staff.

“The teams are incredibly accommodating, so I guess we do feel a sense of community there — but that's there every year, and that hasn't changed, I think, if anything is now more apparent.”

Rahim is also expecting Eid celebrations to be limited to being with her closest family members — her husband and her children — which she said is a huge change from the usual.

She is planning a Zoom dinner with the family, or if lockdown is eased, a smaller dinner with her mother and siblings.

"Ramadan this year has just been really, really different,” Farah Farzana, a junior doctor, told BuzzFeed News.

In normal years she would go for “iftar dates” at her friends’ houses, where they would take turns to host, and then they would head to the mosque for late-night Taraweeh prayers.

“You go to your mosque and you do it with your family and friends and you see the community,” she said. “They have lots of Quran classes. There's lots of things that you can get involved in within the community. We go and give food to neighbours all around the street, etc, and obviously this year many of us are doing iftars by ourselves, all lonely. There's no prayers, all the mosques are shut… It just feels so surreal.”

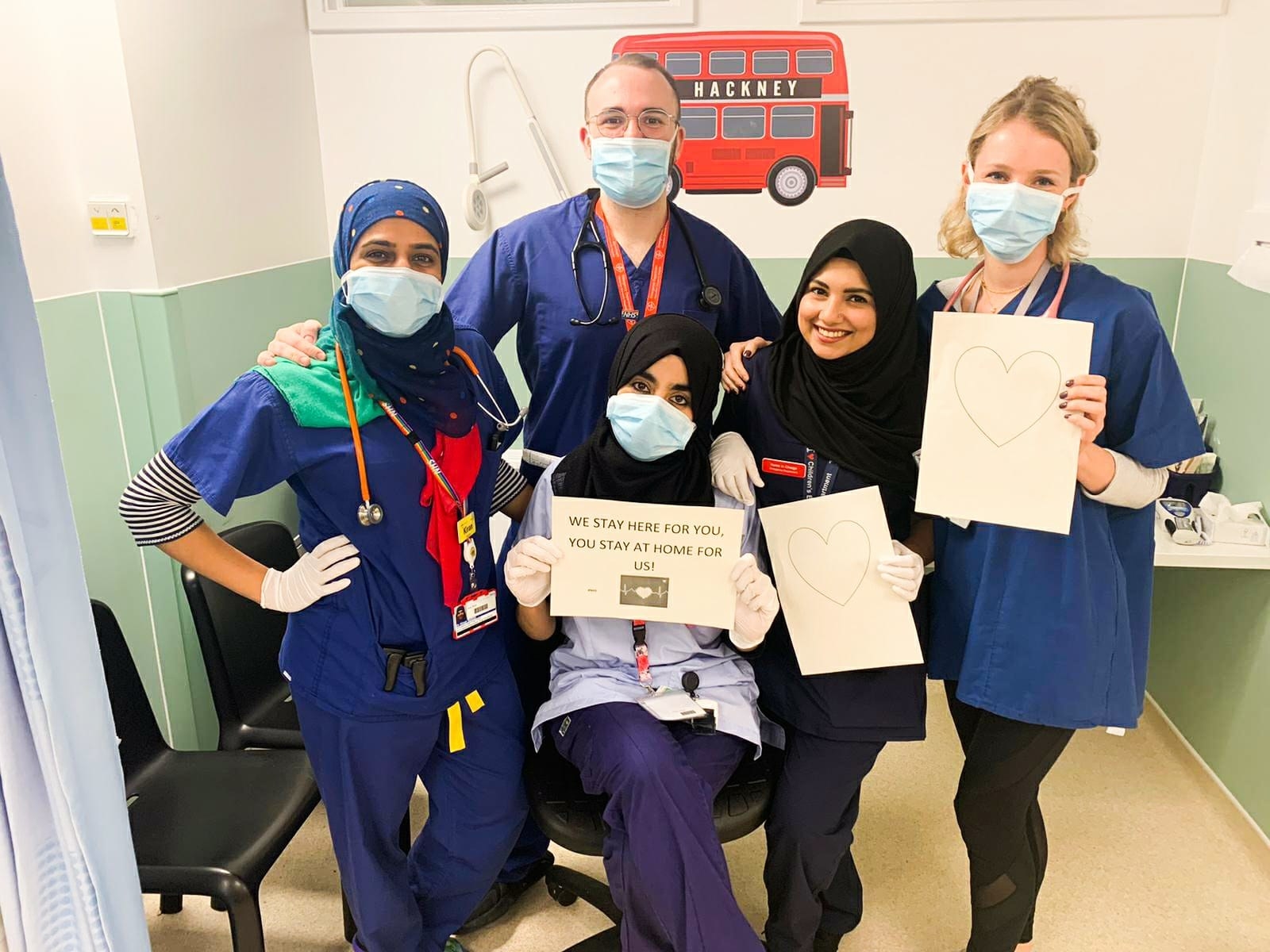

However, at the hospital, Muslim doctors are holding up OK. She has several colleagues who are Muslim, and there is a sense of community.

“There's good spirits at work,” she said. “Some people are still fasting, and obviously it is really difficult. There was one day I had to break my fast because the PPE just got so hot."

Farzana said she has accepted that there are days that she may not be able to fast, but that Muslims do not have to fast — if you are sick, or working a tough shift in heavy PPE on a medical ward, it’s fine to make the days up later or donate some money to charity instead.

“Fasting is never, ever that strict,” she said.

“Allah understands. It's as simple as that,” she added.

“If you’re feeling dehydrated, you can't really make sane decisions, if you're not well yourself, if you're not feeling 100%. So if people are really not feeling up to it, they shouldn't push themselves.”

Farzana said normally hospitals see more people admitted during Ramadan with dehydration, and she worried that with the coronavirus this problem would be worse. However, she said that hasn’t been the case.

“With coronavirus now, I just worried that when you're fasting your immune system’s a bit low, you feel a bit rundown, and corona’s probably going to spread faster, but we're not seeing that yet. So I'm quite happy with that.”

However, one thing that she is missing is the sense of community at work, where she and her Muslim colleagues would break their fasts together.

“After a shift, you’d be in one room, we’d probably eat together, break your fast. We're not really having that now because of social distancing.”

Eid for Farzana will be difficult — she is living with her mum and her brother, and her husband is living separately with his parents, in order to support them.

“It’s hard. I’ve not even given him a hug in the past six, seven weeks,” she said.

“Eid is special because you go to your family, your friend’s houses — you celebrate together," she added. "It’s basically like being alone at Christmas.”

Yassar Mustafa is an ICU doctor. He has been working a mix of night shifts and day shifts during Ramadan, and he said both have their upsides and downsides. Working at night is easier because he can eat and drink for most of the shift, but long shifts mean he misses out on time with his wife and three children.

He said the biggest difference at Ramadan this year is being unable to go to the mosque and take part in community events. He has set up an area at home to pray instead.

“There's more focus on the family and it’s slightly more introspective time Ramadan than previous years obviously as people are diligently following social distancing rules.”

At work, the biggest change is having to wear heavy PPE — gowns, visors, hats, FFP3 face masks — but he said he has still managed to fast every day so far.

“Obviously when you're fasting it can become quite difficult. However, I personally have found it manageable. I make sure before and after the fast — I'm very hydrated. Yes, the key thing really I just made sure I drink a lot of water beforehand and a lot of water at iftar time as well.

“All of the staff on ITU we take regular breaks as well,” he added. “We spend a few hours in PPE and then we come out of the unit for a break, and then we don PPE again, so that definitely helps as well.”

Like other Muslim doctors, he has found Ramadan to be a more lonely affair this year.

“In terms of breaking the fast and suhur time, I'm definitely finding it's more isolating because the shifts are quite long,” he said. “They're about 12 and a half hours.

“Right now I'm on a string of night shifts. So what that means is, unfortunately, I don't have suhur or iftar at home. I take some food with me and I eat in the hospital in my break time essentially."

Although he acknowledges that some people may find it difficult to fast, he said he intends to stick with it if he can.

“Fasting is something I've been looking forward to the whole year,” he said. “I'm sure we all have. And there's a lot of opportunity to improve discipline, to improve spiritually in Ramadan. So I didn't want to pass this opportunity up.

“And obviously, if there was any significant difficulty I know Islamic scholars have said that for frontline key workers there is dispensation. We don't have to fast, but I personally tried it out and felt that it was manageable for me. So for me, it was a case of — if I can do it, I would want to do it to spiritually benefit.”

Due to the ongoing pandemic, all annual leave has been cancelled — which means that Mustafa will miss out on celebrating Eid with his family.

“Eid, unfortunately, I’m actually on long days for the whole weekend,” he said. “All of our annual leave has been cancelled. So unfortunately, I'll be celebrating in the hospital.”

It is not just doctors who are having to adapt during Ramadan — across the NHS Muslim porters, nurses, healthcare assistants, and cleaners are all working hard in the battle against coronavirus.

Zeba Ismaeljibai is a midwife who works in a hospital in the East Midlands. She has mostly been working night shifts, which she said is easier as her working days are 12 and a half hours long.

“In terms of the use of PPE whilst delivering babies, and just the environment, and social distancing even at work, the atmosphere is a lot more different compared to how it usually is in Ramadan,” she said, “but everyone's very supportive, people do relieve you for a quick prayer break, or iftar break, when need be so there’s a good strong sense of community and teamwork, definitely.”

Ismaeljibai lives with her parents and siblings, and she said that during Ramadan in lockdown, “having exclusive time with your family, that’s a positive side to everything, really.”

However, she tries to maintain a level of social distancing at home, does her laundry separately, and has to spend periods eating and praying alone if she has been into contact with symptomatic patients.

“If I’m feeling unwell or if I’ve come into contact with someone with COVID, I try to stay away from my parents as much as possible,” she said. “If I’ve directly looked after someone with COVID, I prefer to just eat on my own, pray on my own, and just maintain some sort of distance.”

As well as adapting to Ramadan, Ismaeljibai said Muslim health workers from BAME backgrounds are also dealing with increased fear of contracting the virus.

“It’s quite a daunting time because the majority of people, healthcare professionals that have passed away that have been infected with COVID have been from black, Asian, and ethnic minority ethnic groups,” she said, “so it is a little bit daunting going into work. I don't think the same sort of pressure is on our white counterparts.”

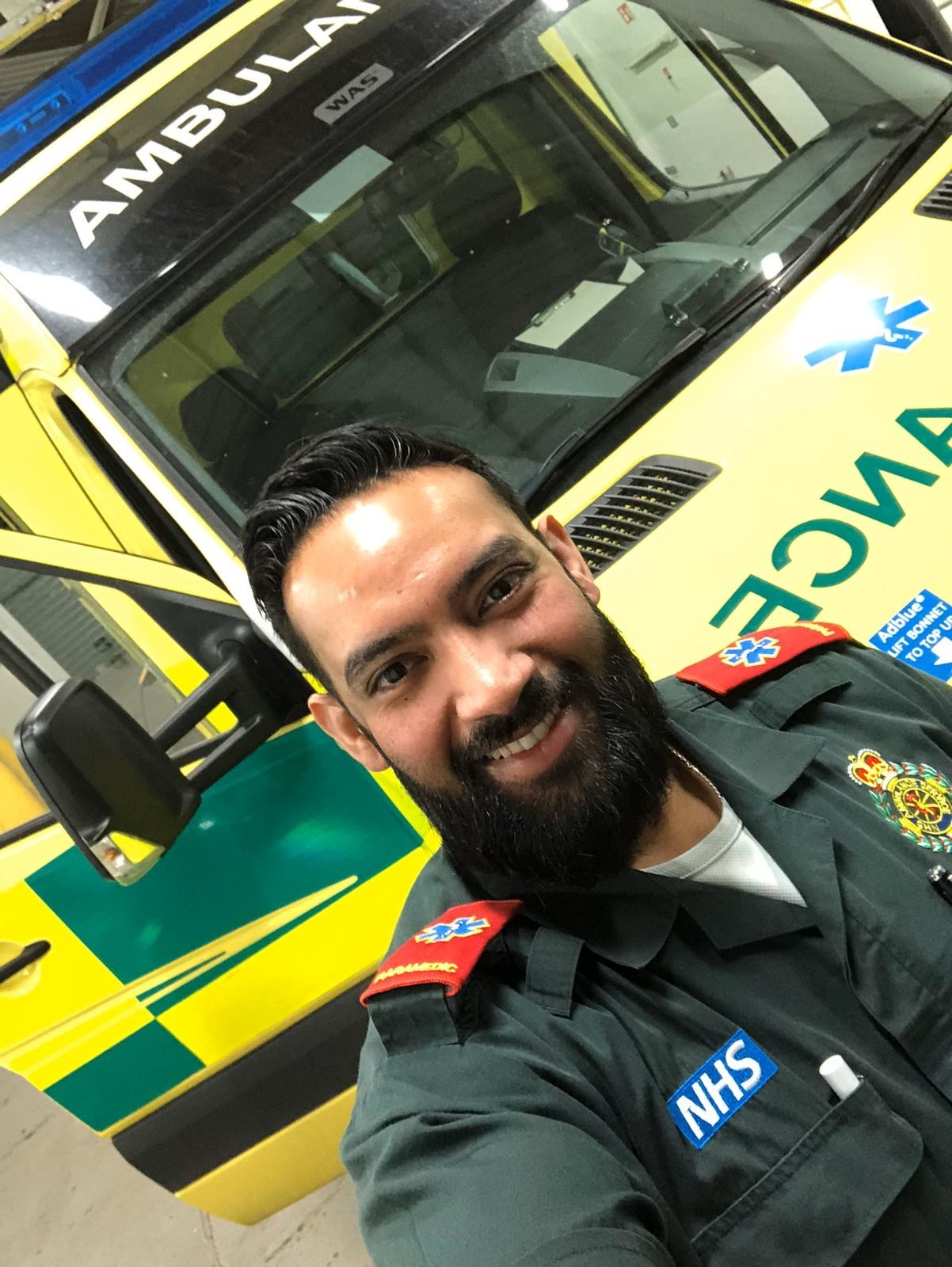

Shumel Rahman is a paramedic. He normally tries to swap to night shifts for the whole month of Ramadan and has done the same this year.

However, this year, he said, “it’s strange, it’s completely different”. He would normally spend his downtime away from work at the mosque, or visiting family and friends, but this year that hasn’t happened.

“It feels like Ramadan, but then it doesn’t at the same time — if that makes sense,” he said.

Like hospital staff, he has to wear PPE and said that working at night makes this easier, and so far he hasn’t had any problems swapping to later shifts.

“Everyone's been really, really good,” he said, “very understanding, very supportive. And luckily, I think I'm quite well-liked there, so that sort of helps. So yeah, it hasn't really been a problem.”

What he thinks many people misunderstand, he said, is that Muslims fast not out of obligation, but because they want to. And that Ramadan is not about fasting, but also a time that people look forward to, to connect with their friends and family, the wider community, and with God.

“I think many people who aren't Muslim don't quite understand Ramadan,” he said, “and maybe see it as a bit of a chore. For Muslims, it’s a very, very special time and something that we actually look forward to, a very important time for us.

Rahman is also down to work during Eid, so he will miss out on some of the celebrations.

“It would be the end of my run of nights, so my plan was, if we did come out of lockdown, I would go to Eid prayers. We have outdoor Eid prayer in Newcastle, so I would literally just come home from work and go to that, and then obviously, if we’re not out of lockdown, I'm planning to do it in my back garden.”

He lives with his wife, children, and his mother, so he will hopefully be able to mark the occasion, and he is also planning to hold a Zoom iftar and a Zoom Eid with his wider family.

“I was hoping we’d be out of lockdown,” he said. “I was really praying for that because I think it’d be good for everyone, everyone spiritually, everyone's mental health. And I think everyone needs a bit of a morale boost, it's become quite difficult for people, I think.

“But people are really saving lives — and we can really see that on the front line — by staying at home and protecting the NHS, so it’s looking at the bigger picture.”