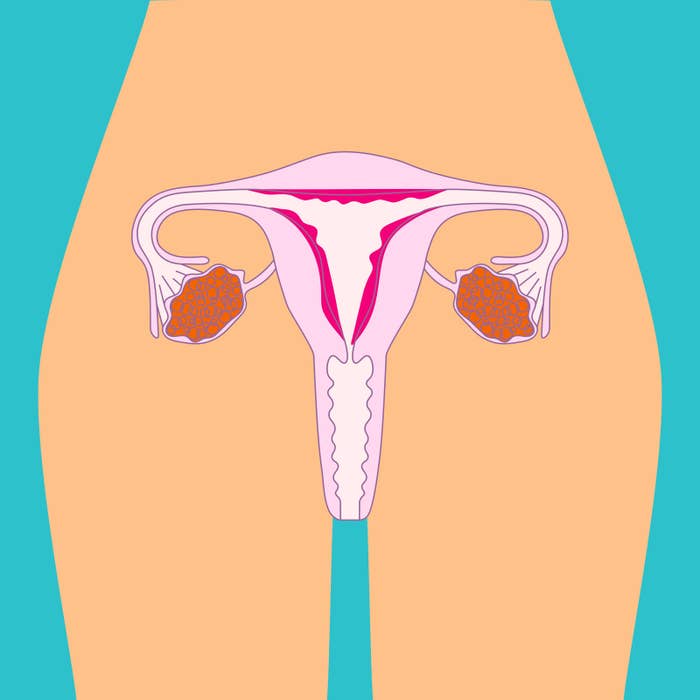

More than 700,000 Australian women have endometriosis, in which cells similar to those that line the uterus grow outside of the uterus, leading to all sorts of symptoms including debilitating pain.

Up to a quarter of women with endometriosis are asymptomatic, but most experience dysmenorrhea (painful periods), chronic pelvic pain and painful sexual intercourse, and between 30% and 50% of endometriosis patients struggle with infertility.

Endometriosis and infertility “go hand in hand” says Melbourne-based advanced laparoscopic and gynaecology surgeon Dr Kenneth Leong.

“On the most basic level endometriosis could cause scarring of the fallopian tubes, which interrupts fertilisation because the egg doesn’t get picked up every month and travel to where it can be fertilised,” Leong, who sub-specialises in infertility and IVF, told BuzzFeed News.

The time it takes a woman with endometriosis to be properly diagnosed in Australia can be “up to nine years”, Leong said.

“I get a lot of patients where, because endometriosis is so under-diagnosed, they come to see me and many years have passed so they have all this inflammation, tissue destruction, distortion of pelvic anatomy and all of this contributes to infertility,” he said.

“In really severe cases where you have this inflammation and your pelvic cavity is just really angry with the disease, the egg quality can actually get affected and there are studies that show it can affect the quality of your endometrial lining, which affects egg plantation,” he said.

Leong said the “gold standard” for diagnosing endometriosis remains a laparoscopy — a keyhole surgery used to examine or operate on the interior of the abdominal or pelvic cavities.

“During a laparoscopy, you can sight the lesions, you remove them completely and get some tissue to confirm it is endometriosis,” he said.

“If it is in the early stages, it is quite easy to treat and you just excise it completely when it hasn’t done enough damage to wreck your fallopian tubes and reproductive organs.

“In that stage, I would put the patient on a contraceptive if they aren’t looking to conceive yet and keep them in a holding pattern.”

Hormonal contraception can be used to treat the symptoms of endometriosis to suppress menstruation (which is when endometriosis symptoms can be worse) or replace it with a milder version of menstruation, a withdrawal bleed.

Some patients will have a laparoscopy and have endometriosis removed as well as potentially their “tubes flushed”, Leong said, before trying to conceive.

“Up to 80% of my patients would have endometriosis and I find about 30% of them would conceive within three to six months after treatment,” he said.

Many of Leong’s patients with endometriosis will eventually successfully conceive with assisted reproductive technology such as IVF, he said.

The federal government’s National Action Plan for Endometriosis, released in July last year, acknowledges endometriosis is “chronic”, “common”, “frequently under-recognised” and that it impacts the “social and economic participation, physiological, mental and psychosocial health of those affected”.

Tasmanian woman Kaitlyn Graham was on the oral contraceptive pill throughout high school and didn’t experience painful periods until she went off it in 2015 and noticed her menstrual cycle was “super wacky”.

“I could never quite pinpoint when I might be ovulating or when my period might be, and I was getting funny digestive symptoms and pain,” the 25-year-old told BuzzFeed News. “We kept trying for a pregnancy but something wasn’t quite right.”

Graham was sent away “disheartened” by the first gynaecologist she saw, but two years later she had a laparoscopy and was diagnosed with endometriosis.

“They scraped the uterus and the surgeon who did it said I would be super fertile for the next six months,” she said. “My surgery was in July, we found out we were pregnant in August and we lost the baby in October.”

After the miscarriage, Graham said she was told to wait for the first period and then track her cycle and start trying once she was ovulating again.

“We are pretty keen to fall pregnant and if we haven’t in the next few months we might look into intrauterine insemination (IUI) or IVF,” she said. “I just want to make sure I have time to make [decisions about assisted reproductive technology].”

Graham said there has been an “emotional toll of not knowing”.

“I feel like I’m a bit of a ticking time bomb,” she said. “I would like to be on contraception because it would stop some of my symptoms, but I am off it until we have a baby.”

A study published in January in the journal Translational Medicine shed light on how the inner lining of the uterus of women who were infertile as a result of endometriosis was low in a particular enzyme.

The enzyme, HDAC3, assists in gene regulation and expression — and when there is a deficiency in this enzyme, the genetic processes needed to support pregnancy in the uterus are disturbed.

Bronte Coates feels “lucky” she has a healthy 2-month-old baby daughter but says the past three years trying to start a family have been “quite distressing”.

“When I was 28 my partner and I started trying to conceive and we got pregnant and had a miscarriage within the first six months,” the now 31-year-old Melbourne mother told BuzzFeed News.

“Because of my age we didn’t really investigate it for another year and kept trying.”

Coates said when she had an ultrasound the doctor said she might have endometriosis and a fertility specialist suggested the same.

“I thought she was insane because endometriosis is so varied and because most people I know have such severe pain, I didn’t think I had it,” Coates said.

“You don’t really know how painful your periods are meant to be and you’re just told they are painful and then you expect them to be painful.”

Coates had a laparoscopy through the private system for which she paid almost $4,000, including specialist consultation. The operation revealed she had stage three (moderate) endometriosis.

“A lot of the endo was on my bowel wall and [the surgeon] couldn’t remove all of it without bowel surgery,” she said.

Coates had long had gastrointestinal issues, which her doctor later told her could be a symptom of endometriosis.

“The problem with endometriosis is that it is a catch-all term in some ways because it can be so varied and there are so many symptoms, so if I had known my digestive symptoms were potentially endometriosis symptoms, I might have thought about it.”

Coates fell pregnant within two months of the surgery.

“I felt really lucky,” she said. “I wish we had investigated this earlier because when you’re trying to conceive and people are telling you you’re just stressed and not to worry, you feel a bit crazy.”