The last conversation I had with my father was on Christmas Eve. We’d decided to meet for coffee and I’d shown up right on time. Even though he was usually punctual, if not early, there was no sign of him.

In a way I was relieved. This meant I could order my cup of coffee without worrying about my dad using funds he might not have to pay for it. I was always grateful for the gesture, but more often felt guilty since I was never sure if he was working or between jobs or relying on his current wife for finances.

The shop was empty except for a couple perched at a high table near the pickup counter. I sat in an armchair facing the front door. It was five minutes past the time we’d agreed to meet. I wondered if he’d forgotten, even though he’d texted me an hour earlier that he was coming. Ten minutes went by. Fifteen. And there he was. He had a deep gash on the side of his face that looked fairly recent. I didn’t know what to make of it. Had he gotten into a fight? That wasn’t like him. Was it a drinking-related accident? But when he stepped forward to hug me, I didn’t smell any hint of liquor. He smiled, as if the wound weren’t a current concern.

I was always nervous and apprehensive every time we met during the holidays. My father had fluctuated between drinking and sobriety for as long as I could remember, which eventually led to my parent’s divorce when I started high school. There were several years in between when we didn’t talk, but for the last six years I’d wanted to make an effort to get to know him better. Our conversations usually centered around catching up on what we’d been doing for the last few months.

We’d been talking for 10 minutes when he brought up the gash on his face.

“You’re probably wondering what happened, huh?”

I was, but I hadn’t said anything at first because I didn’t want to be rude.

“It looks pretty deep,” I said.

He told me that his new wife wasn’t doing well. In a fit of hysterics, she had demanded all the Christmas decorations be taken down and put away. He recalled how she had knocked the tree right into his face, and that’s how the lights strung upon the branches electrocuted his cheek.

“I’m sorry,” I’d told him, looking into his eyes. I wasn’t searching for the truth in them, but for sobriety. I was convinced I'd found it. “But you’re okay?”

“Oh, I’m fine,” he said with a reassuring smile. “I’m doing just fine. Did I tell you? Had to get a tooth pulled. I couldn’t pay for it. But my dentist — real nice guy — he said, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ He goes, ‘Merry Christmas.’ And I was able to have it removed.”

I wanted to believe he was sober. He’d suffered and survived a heart attack back in 2013, and to my knowledge he was taking his health seriously. But I wasn’t my mother, who could always tell when he’d been drinking even if he hid it well. It was in his eyes, she said, but I could never tell. I only knew the obvious signs, which were the slurring and stumbling and sharp smell of liquor. The yelling that came with the consumption of too much beer. None of that was present now. I assumed he must have kept his promise to me and remained sober, but I’d been wrong before.

After an hour, we parted ways. He wrapped me in a hug in the parking lot outside, holding on just a little tighter at the end. I was always first to let go. He watched me drive away first before getting in his car and doing the same.

When I got home I texted him, Merry Christmas, Dad. Love you!

He never responded.

I played the conversation over in my mind on the drive home. I knew something was off. If my father’s struggle with alcoholism had taught me anything over the past 26 years, it was that it displayed itself in different forms. His struggle wasn’t linear, but a jagged, rough line that dipped and curved up and down. Even if the obvious signs weren’t there, the lack of cohesiveness in his stories told me he was still suffering. But despite all the warning signs, despite the pit in my stomach that told me something was off, I didn't say anything to him. Not to him — or to anyone.

My dad died at the beginning of 2016. He was a lot of different things — an entrepreneur, a program manager, a husband. He was a brother, a creator, and a friend. He was smart and kind and generous.

And he struggled with alcohol addiction.

In AA a big part of addressing you have a problem is admitting it, but learning how to admit to my father's problem is something I've been working on for quite some time too.

I can trace his struggle with alcohol back to when I was about 6. We were attending Thanksgiving dinner at my aunt’s house, and he’d opened a Budweiser. In my 6-year-old brain, fizzy drinks that came in cans tasted like sugary soda, so I asked if I could try it. I remember him explaining that it was beer, and that I wouldn’t like it, but I was sure I would because I loved Coca-Cola. I still don’t know why he offered the can to me. I took a drink, recoiling at the way the bitter bubbles hit my tongue. He laughed, like he knew this would happen. “Not very good, huh?”

That moment led to a disconnect throughout elementary school. If it tasted so terrible, why did he drink so much of it? Why did he like getting drunk? Why did the drinking always make him angry?

When I was 11, I was well aware that my father's fizzy drink affinity was more than just a beverage preference. I remember finding a jug of Carlo Rossi wine hidden behind my sister’s dollhouse. It was jarring because he’d been out of rehab for several months and each time he came home, I had a renewed hope that this time he wouldn’t go back.

My dad was the one who explained alcoholism to me as a disease, but even so I wanted to hope for his sobriety. Going in and out of treatment centers wasn’t like removing a tumor. There wasn’t any kind of physical evidence, body scan, or test that could provide concrete evidence he’d never be tempted to drink again. I was old enough to understand the concept of addiction. But despite understanding it, I couldn't wrap my head around why it was so hard for him to stop — especially when quitting meant putting an end to the hurt it caused me.

There’s a shameful stigma that surrounds alcoholism. People who have an addiction are often blamed for the problem or seen as weak for not being able to control it. It’s almost a cultural norm for people to make offhanded "alcoholic" jokes on sitcoms or portray characters with alcoholism crudely and without consequence. If you were to joke about something as awful and serious as cancer, people would probably react by saying, “What the hell is wrong with you?” It’s easier to empathize with those who didn’t ask for illness than on those who seemingly self-destruct.

Addiction is a complicated illness. It’s easy to automatically want to blame the person when a relapse occurs, as I did for several years. My dad’s behavior of remaining sober but eventually drinking again was a pattern. Things looked up when my sister was born, but he was back in another treatment center a few years later. He attended Alcoholics Anonymous and rehabs and up-and-coming programs that promised help. They would for a while. His drunken tirades and furious yelling would subside for a few months, but ultimately his sobriety wouldn’t last long.

Back in second grade, I assumed that everyone’s father drank to the extent of getting drunk, loud, and angry at home. It was just a normal part of people’s households that no one talked about, just like I didn’t talk about it. When I later realized this was false, it was my shame that kept me quiet about his struggle. I was embarrassed that all my friend’s fathers knew how to behave like dads, but mine was unpredictable. Mostly I was confused. I knew my dad loved me, and that he was capable of expressing love when he wasn’t drinking, but the yelling that came with the consumption of alcohol was intimidating. I didn’t know who to turn to, so I turned inward. I kept the guilt, fear, shame, anger, and embarrassment to myself.

When I was 13, my father’s disease reared its ugliest head. Even if my mom emptied our house of hidden alcohol, he would still find a way to get it. The rages turned to blackouts. The fights got so bad my mom simply couldn't put up with it anymore. So finally, they separated.

Then I lost my best friend.

Lauren and I didn't fall out of touch like most teen girls do over boys, or music, or getting placed on different sports teams. Instead we fell out of touch because during the separation, my mom had reached out to Lauren’s parents for help. The good thing about being friends with Lauren was that our parents were friends, which meant we got to see a lot of each other. But it was then that they learned the truth about my dad’s alcoholism and of the upcoming divorce. Her parents provided the support my mom needed, but after that day I barely saw Lauren. The closeness we once had was gone.

Her parents decided to put distance between their family and ours. I wasn’t mad at my mom, and I didn’t blame her. Instead, my initial belief was reaffirmed: You don’t talk about someone you love suffering from addiction, because then you become a problem no one wants to deal with.

Not too long after losing Lauren, I learned how to internalize my feelings about my father’s alcoholism. The divorce was messy and the topic of his addiction was delicate. There wasn’t anyone I knew who was going through the same thing. I struggled with sadness, confusion, and guilt that I couldn’t fully pinpoint because at the surface of all my emotions was anger. I wanted him to be better. Why wasn’t it easy? It felt like he was making a choice and he’d picked the decision to drink over his family.

I was a freshman in high school the first time I tried to reach out to someone, even if that decision came subconsciously. My English teacher had assigned the class an essay that required us to write about an object that meant at lot to us. I chose to write about my childhood pillow that I still kept with me. I don’t know why I decided to bare my soul in this paper, but I wrote about why hugging the pillow became a comforting ritual when my dad was drunk and yelling downstairs. I poured out my feelings of isolation and loneliness and fear and shame.

When it came time to critique these essays, my teacher grouped us into pods of four. I waited silently as my paper was passed around. My heart raced in my chest. What feedback would my classmates have? Would they pity me? Would they express that their dads had the same struggle as mine?

No one said anything. The edits were minimal. After it was graded, part of me wanted my teacher to say something when she handed it back. I hoped she would acknowledge what I’d been going through. More that that, I wanted to not feel so alone.

In the end, she didn’t say anything. I got a B on the paper.

It’s been two years since my father died. There are times when it doesn’t feel real. Then there are other times where it feels too real, and the expanding cavity of his absence aches through me. It hits me the most when I go back home, when I visit that local coffee shop where we often met, knowing that no matter how long I wait, he’ll never again walk through those doors.

We had a complex relationship, and it’s one that is complicated to talk about. I wish I could say I've come more to terms with this, or that I've suddenly become the type of person who can easily open up about my father's struggle. It’s difficult, and it makes me feel vulnerable. I still feel an uncomfortable sadness when I catch the familiar scent of stale, day-after booze on someone or when I see an angry, drunken fight break out in a bar.

But I’ve found that I can talk about him when certain memories stir inside me. When my sister and I get together, it’s freeing to share about our separate memories we have growing up — both the good and the bad. And talking about it eases something in my chest, as if my voice was a knot I kept tied tight for so long and I’ve slowly gained the courage to loosen it.

Another Christmas Eve, a few years before my father died, we met at a sad-looking Chinese buffet in dire need of a paint job. Surrounded by loud, clattering plates and children squealing with delight in front of the soft-serve machine, we found a two-person table in the center of the chaos. He asked me how my job was and if I was happy and how my relationship was going, and through bites of my spring rolls I answered and offered up a small summary of a book idea I’d been sitting on.

“You always knew how to tell a story.” He smiled, the kind, sober smile that lit up his green eyes. The same color green I’d inherited. “Maybe one day you’ll write a story about my life. Wouldn’t that be something?”

“It’d be something,” I agreed.

“Sure would.”

I’m not the person who should tell my father’s stories. Or maybe I am. Maybe some of them are mine to tell. Here’s what I know: I lived through his alcoholism, but his struggle didn’t make him a bad person. My dad suffered in a way I’ll never fully understand. He was addicted to alcohol, but he wasn’t defined by his alcoholism. His choices hurt me, even though those choices were never meant to hurt me. Finally opening up about this doesn’t fill me with the shame and anger I had experienced for so long, and it’s taken a number of therapy sessions and thoughtful reflection to be able to accept that his addiction was out of my control. Nothing I could have done would have changed him. It doesn’t stop me from wishing that weren’t true.

“What kind of story would it be?” I asked as he picked at his rice. “A sad or a happy one?”

He let the pause hang in the air before saying, “A little of both.”

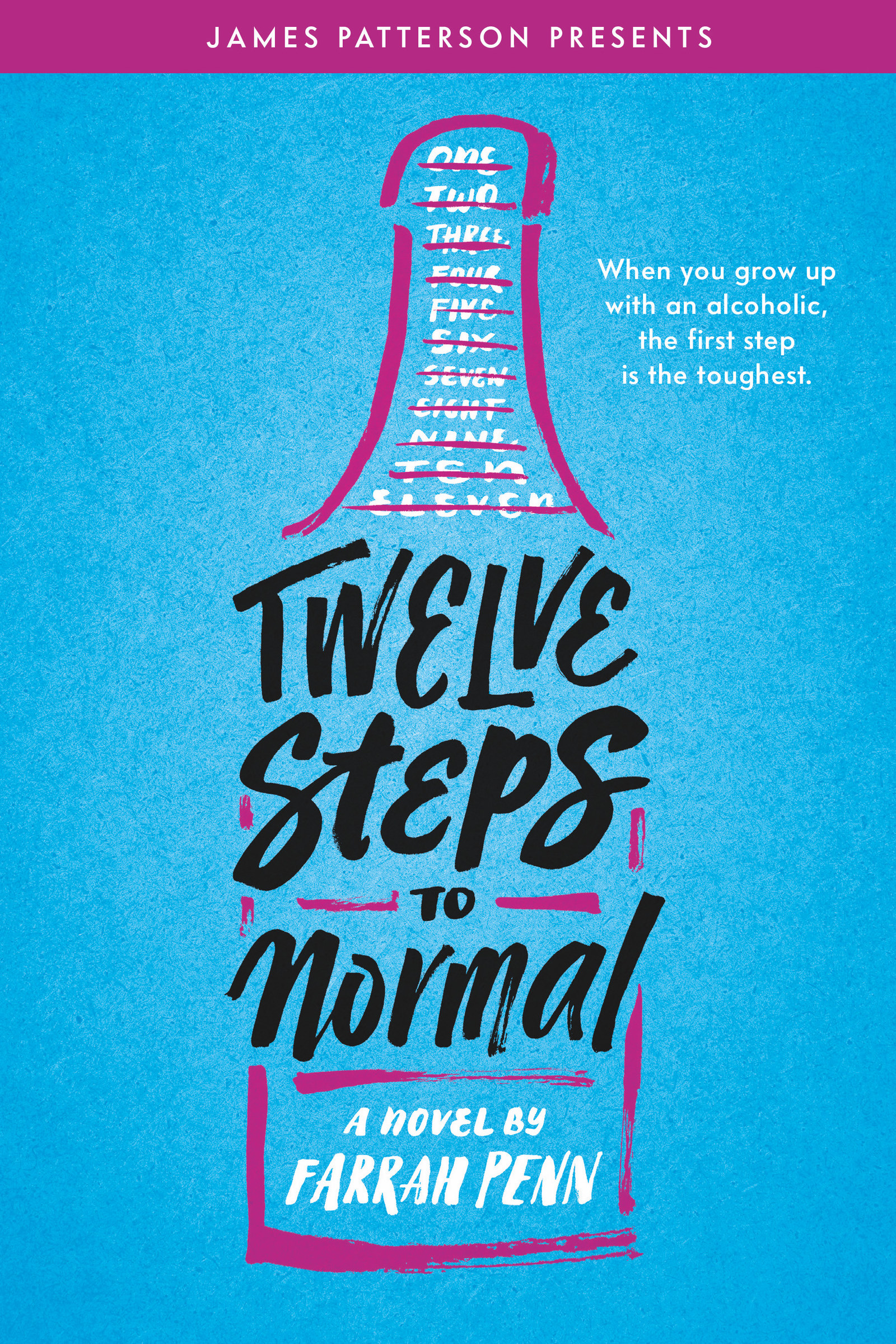

Farrah Penn was born and raised in a suburb in Texas but now resides in Los Angeles with her gremlin dog and succulents. When she’s not writing books, she can be found writing content for BuzzFeed and sending texts that contain too many emojis. Twelve Steps to Normal is her first novel. You can follow her @FarrahPenn and check out her writing here.

Learn more about Twelve Steps to Normal here.