Growing up with four older brothers, I learned to spit, swear, and swing. My family members called me a tomboy because I wasn’t interested in traditionally feminine things. I dressed in my brothers’ hand-me-downs, hid my hair under beanies and bandanas until I chopped it off in high school. I only wore makeup when my friends gave me makeovers. When I was forced to wear a dress for school dances, I felt embarrassed and grotesque no matter how much people told me I looked prettier, better, and like a girl for once. When I came out at age 15, I thought Of course, that finally explains it! I don’t look like other girls because I’m gay.

I grew up in rural Louisiana, where my town seemed stuck in another time: Pop culture took longer to reach us (top 40 songs didn’t hit our radio waves until a year after their release); the community was close-knit and closed off (few people moved into town and even fewer moved out); the internet was only accessible in one-hour intervals at the local library (and I didn’t dare look up queer stuff there).

When I came out, the only other queer people I knew were on television. Something as simple as queer representation in pop culture kept my head above water between the ages of 12 and 15 as I struggled to accept my sexuality. It gave me hope. But, according to television, queer people didn’t live in small southern towns — they lived in one of two places: California or Canada. Places that existed in an entirely different world from my own, a world I thought was either unreal or unreachable. And there was another problem, too: None of them looked like me.

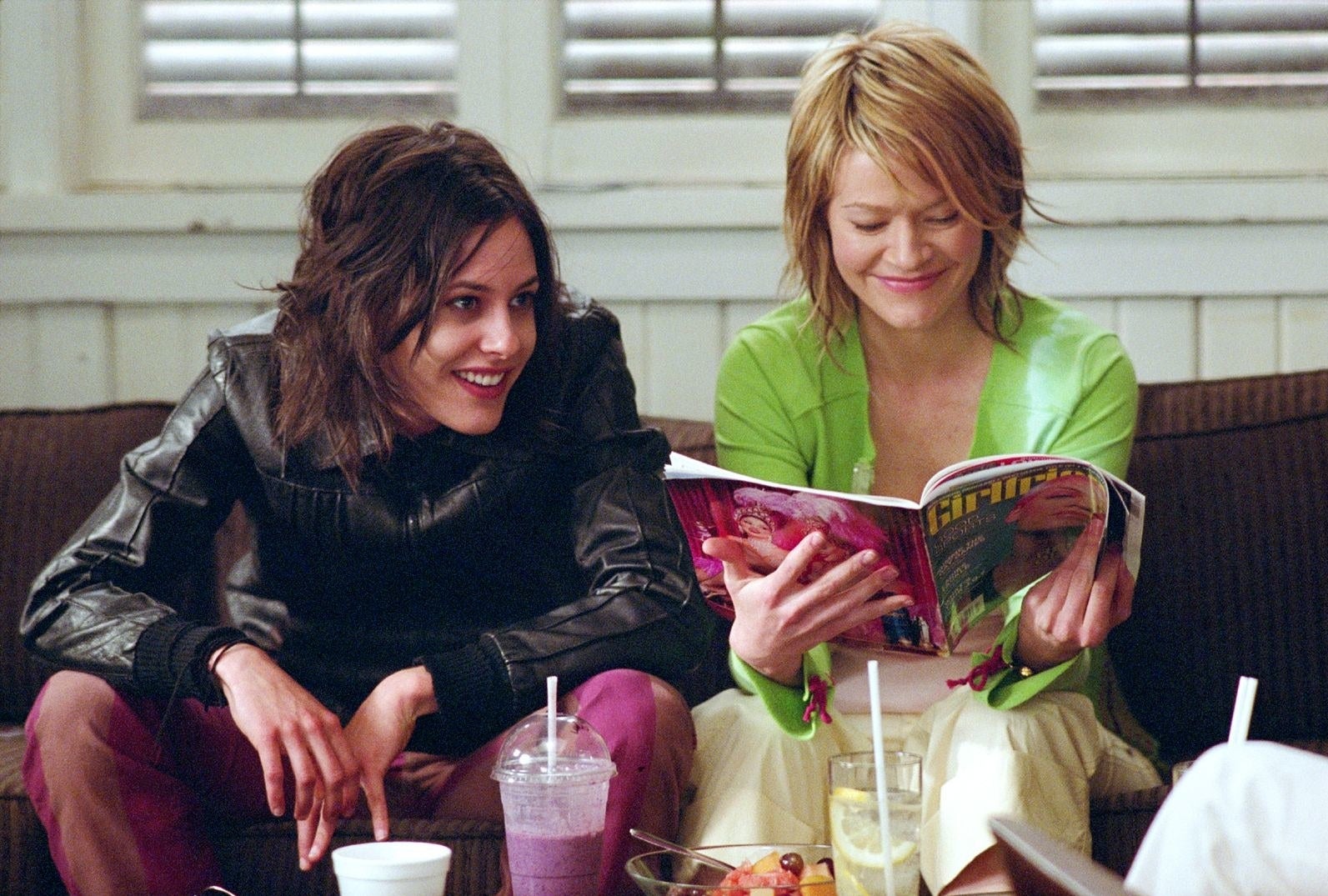

In the mid-2000s, just as I was coming out and coming of age, there was a surge of queer-centric storylines on television: Marissa and Alex’s five-episode relationship arc on The OC, Paige and Alex’s storyline on Degrassi, and everything that happened on South of Nowhere, a show centered on a teenager questioning her sexuality. With each new depiction, I noticed that all of the women were feminine. I was not.

Even now, when there are more LGBT characters on television than ever before, portrayals of queer women continue to cater to the male gaze. Romantic pairings between women are almost universally femme/femme. One is blonde, one is brunette. One is bubbly, one is broody. Most are named “Alex.” But they’re all femme/femme. Think about it: Callie and Arizona, Brittany and Santana, Spencer and Ashley, Paige and Alex, Piper and Alex, Marissa and Alex, Maggie and Alex, Clarke and Lexa, Emily and Naomi, Willow and Tara, Pam and Tara, Bette and Tina (and almost every other L Word pairing), Susan and Carol, Bo and Lauren, Nomi and Amanita, Emily and Maya/Paige/Alison, Waverly and Nicole, Cosima and Delphine, Annalise and Eve, Root and Shaw, Luisa and Rose, Amy and Karma/Reagan, Kelly and Yorkie, Niko and Karolina, Anissa and Grace...the list goes on.

Of course, femme lesbians exist in the real world, and representation is important. But a show is no longer revolutionary simply for including the token, just-happens-to-be-a-lesbian character and her conventionally attractive love interest. Sexuality is not always an incidental aspect of people’s lives; for many queer people, femme lesbians included, our queerness is an identity that carries with it the weight of an entire history and subculture. The message of so many incidentally queer femme portrayals is that women are allowed to be gay as long as they aren’t too gay. For the most part, queer women on television must follow three rules: They can’t “look” like a stereotypical lesbian, they can’t discuss queer culture, and they must remain appealing to men.

It wasn’t until my girlfriend and I binge-watched the The L Word, another product of the mid-2000s, that I first saw a reflection of myself and my identity on television. Shane McCutcheon (if you can’t tell by the unisex name) was the resident androgynous character, the closest the show ever came to depicting a butch woman. Shane was all shaggy hair, strut, and swagger: the straight girl heartbreaker. My girlfriend had a crush on her; I wanted to be her.

Because of our culture's obsession with dichotomies, I knew that if I wasn’t a feminine lesbian, I must be a butch one. “Butch” sounded dirty and insulting, like “dyke,” the word word hurled at me by strangers on sidewalks. The word “butch” followed me, a stray nipping at my heels, but I ultimately refused bring it home. I didn’t want to slap on another label that further alienated me from society. I wasn’t butch, and I wasn’t dykey, I told myself. I was androgynous, like Shane.

But Shane wasn’t really a reflection of me; she was a distortion. A funhouse mirror. Sometimes she had short hair and wore ties, and her magnetism was undeniable, but she also wore flowy low-cut tops and lipstick (especially in the promotional photos). The character was written to have universal sex appeal. In a 2008 interview with After Ellen, Kate Moennig, the actor who played Shane, even resisted labeling the character as butch: “I never thought Shane was a butch. Actually, I don’t like it when she’s called that. I just think it’s such an obvious stereotype to throw her into and it’s not true at all. But androgynous, yeah.” Shane was, if anything, a sanitized version of butch — nonthreatening, safe enough for straight women to desire.

Real-life lesbians have also been de-butched for mainstream audiences. Ellen DeGeneres and Rachel Maddow, two of the most powerful masculine-presenting women in media, have been softened and feminized for television. Ellen, in all of her tailored suit glory, is a CoverGirl — the literal face of feminine beauty standards. For Rachel Maddow, dressing more feminine is just a part of the job. In a recent New Yorker profile, Janet Malcolm documents Maddow’s after-show transition from her television persona to her true self: “Next, she removes her contact lenses and puts on horn-rimmed glasses that hide the bluish eyeshadow a makeup man hastily applied two minutes before the show. She now looks like a tall, gangly tomboy instead of the delicately handsome woman with a stylish boy’s bob.” Both are allowed to toe the line of masculinity, but never fully cross it.

Depictions of butch and masculine-of-center characters remain not only rare, but steeped in stereotypes. Autostraddle counted 16 masculine-of-center characters on television in 2017 and noticed a troubling trend:

Butches are most likely to appear in prison or somehow involved in crime or criminal justice. Lucy is a convicted rapist. Franky, Silent Ann and Big Boo are all convicted criminals. Jukebox is a (now-killed) corrupt cop. Mary Agnes and Stef are both gun-toting law enforcers, albeit in very different scenarios. Ally kills humans with knives and Lena works for a Hollywood “fixer” who’s often helping criminals get away with it.

Orange Is the New Black, which boasted the most lesbian characters onscreen in 2017, is a frequent offender of these tropes. The main queer romance between Piper and Alex is, of course, femme/femme. Big Boo, played by proud butch Lea DeLaria, is the butt of jokes, has “prison wives,” and loses custody of her emotional support dog after forcing it to perform sex acts on her. (To the show’s credit, Big Boo is fleshed out more in Season 3 via a flashback depicting her mother’s refusal to accept Boo’s authentically butch self and in subsequent seasons through her friendship with fellow inmate Tiffany Doggett.)

Orange Is the New Black was also the first mainstream show to depict a black, masculine-of -center coming out story with a Poussey-centric flashback in Season 2 — however, Poussey, played by Samira Wiley, was crushed to death by a guard in Season 4, becoming another in a long line of dead lesbians on television.

The few masculine-of-center characters outside of OITNB in 2017 were often just as troubling. Two characters have died and three were on shows that have since been canceled. Intersectionality and diversity is especially lacking; out of 16 characters, only three were Latinx, three were black, and none were Asian or Pacific Islander.

By 2016, the tides seemed to be turning in favor of more nuanced portrayals of gender and sexuality on television. Take My Wife, created by married comics Rhea Butcher and Cameron Esposito, aired on Seeso, a comedy streaming service, and Tig Notaro’s One Mississippi, starring Notaro and real-life wife Stephanie Allynne, premiered on Amazon. The two shows were only available via streaming platforms, part of a new wave of more niche LGBT-centric programming that began with Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black in 2013 and Amazon’s Transparent the following year. Despite their limited distribution, both Take My Wife and One Mississippi were truly groundbreaking in their depiction of masculine-of-center characters.

In Take My Wife, Butcher and Esposito play fictionalized versions of themselves trying to balance their relationship with their careers as comics. The brief six-episode season tackles sexism in the stand-up community and the pervasiveness of sexual assault (all of this long before the #MeToo movement).

Their queerness is explicit, matter-of-fact, and often used as material in their stand-up routines: “As you can tell by my haircut, I am a...Thundercat, and also a giant lesbian,” and “My name is Rhea Butcher; it’s funny because it’s true. I’m 100% butcher than all of you.” These and other queer cultural references elevate the show, giving audiences authenticity in lieu of more tired U-Haul jokes.

The relationship between the two characters, both of whom inhabit the butch spectrum, is lived-in and comfortable as well as sexy and romantic. They bicker and wear pajamas and eat Chinese take-out, just like straight couples! Combine Esposito's chiseled cheekbones, Butcher’s perfect pompadour, and their leather jacket collection and you get the ultimate butch icon: James Dean.

One Mississippi is similarly rooted in realistic portrayals of queer relationships. The show’s first season is a gut-punching portrait of grief and its lingering effects. Tig, an LA radio host, returns home to Mississippi after the sudden death of her mother. She moves back in with her brother and their idiosyncratic stepfather, and the three of them navigate their new familial relationship after the loss of their matriarch. Tig pulls away from her girlfriend Brooke and her life in Los Angeles as she rediscovers the beauty of the small town she left behind.

Tig has an established girlfriend in Season 1, casually dates in Season 2, and has a slow-burn romance with “Straight Kate.” The show refreshingly allows a queer woman to explore different types of relationships and relationship stages all while comfortably wearing a pair of jeans, a hoodie, and sneakers. Plus, Season 2 addresses workplace sexual harassment, the south’s troubled history with race, childhood molestation, and LGBT discrimination — heavy stuff, to be sure, but Notaro’s dry humor and sarcastic wit add levity.

One Mississippi showed me a modern butch/femme pairing set in a small southern town like the one I grew up in. It was a premise I was familiar with, but never thought I would see on TV: a masculine-of-center woman returning home and falling in love in a place where queer people aren’t supposed to have happy endings. It felt like I was getting the butch back pay I was owed.

In 2017, Lena Waithe’s now Emmy-winning episode of Master of None, “Thanksgiving,” showed another groundbreaking black, masculine-of-center coming out story. In one scene set in 1995, Denise’s mother gives her a frilly dress to wear for dinner. She tries on the dress and looks at herself in the mirror. Twisting her face, she says, “Man, this is some bullshit.” The next scene cuts to 12-year-old Denise sauntering down the stairs to Biggie in a backward-facing hat and Jordans. In a span of 22 years, Denise continues to explore her gender and sexuality.

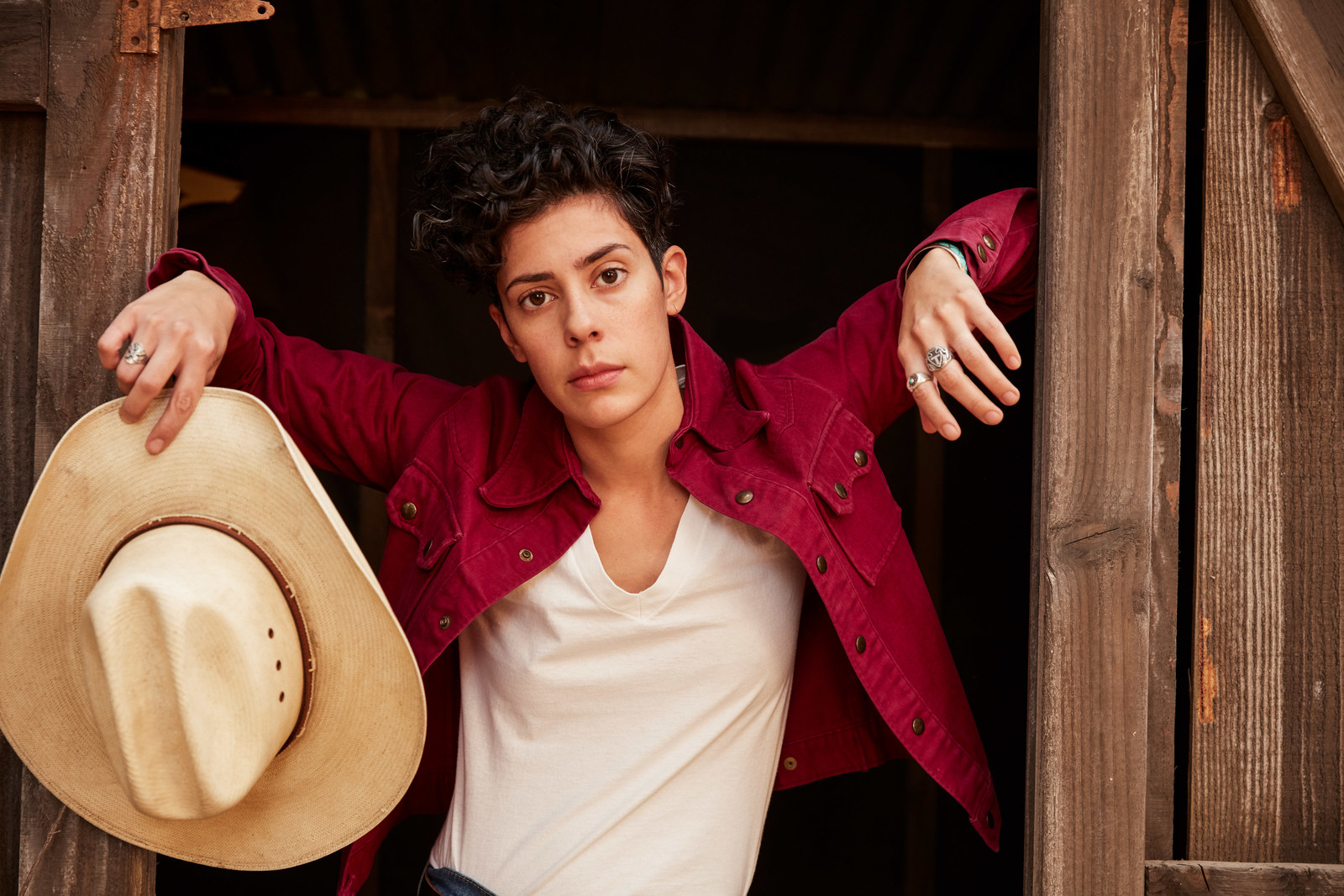

On Amazon’s I Love Dick, Roberta Colindrez plays Devon, a masculine-of-center Latinx artist. Like One Mississippi, the series is set in a small southern town, this time in Texas, and Devon dresses the part in a pair of Wranglers and cowboy boots. In a flashback, Devon argues with her mother. “We don’t talk like that in this house; it’s not ladylike,” her mother says. “I’m not a lady,” Devon says.

Until this point, television has given us a very limited definition of butchness and assigned-female masculinity. Tig, Rhea, Cameron, Devon, Poussey, and Denise are authentically “butch” characters, but each of them are butch in their own way. Devon and Rhea blur the line between the binary, even existing outside of it; Tig, comfortable in her skin, effortlessly alternates between tailored blazers and dressing like a teenager; Denise is the definition of dapper; and Cameron gifted the world a truly remarkable side mullet (RIP).

But these very different characters have a couple other things in common: all of them were played by queer actors, and there's a high chance that none of them will be onscreen again in 2018.

In November 2017, the streaming service Seeso shut down, taking Take My Wife with it. Butcher and Esposito are still shopping their second season to other networks. Joanna Robinson at Vanity Fair wrote that “If she and Esposito can’t find a new platform for the episodes that are already done and dusted, the second season of the politically relevant and utterly charming Take My Wife may never see the light of day.”

Confronting Hollywood’s imbalance of power, Butcher and Esposito prioritized hiring women, queer people, and people of color in order “to claim our space and make room for others.” And Seeso, by selling content directly to consumers, offered them the creative freedom and flexibility to do so. The unprecedented move made the show revolutionary both onscreen and behind the scenes, which made SeeSo’s collapse all the more disappointing.

In January, Amazon canceled One Mississippi and I Love Dick. According to the New York Times, “The studio will now turn its attention toward larger projects, including its $200 million prize acquisition: an adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.” Both shows, despite their merits, were deemed disposable after failing to reach mainstream audiences and garner the requisite awards while Transparent, winner of two Golden Globes and eight Emmys, remains on Amazon’s lineup. Transparent’s fifth season has been confirmed though lead actor Jeffrey Tambor exited the series following multiple sexual harassment allegations.

Concerning Master of None, Aziz Ansari stated in a 2017 interview with GQ, “My life has not progressed enough for me to write season three yet.” Following Ansari’s own sexual misconduct allegations in January, no other updates have surfaced. Lena Waithe, who is currently working on her Showtime series, The Chi, has not expressed whether or not she would be involved in a hypothetical Season 3.

The masculine-of-center characters we'll likely see again in the future aren't faring well. Susie from The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel is Ambiguously Gay; her sexuality has not been explicitly confirmed in the series. And in the Emmy-winning The Handmaid’s Tale, Moira (Samira Wiley) almost escapes the patriarchal dystopia, but is instead caught and forced into prostitution. This, after a different lesbian character was genitally mutilated to “cure” her deviant sexual urges. Even now, queer characters on television are still coded, tortured or punished.

The majority of masculine-of-center characters on television fall into two categories: masculine in appearance only (Ivy from American Horror Story: Cult...kinda) or masculine in demeanor only (Franky from Wentworth). Rarely is there a nuanced combination of the two.

Navigating the world in a butch body is isolating. Though I have butch friends, I’m frequently the only person in a room who looks like me. The rare glimpses I get of authentically butch characters onscreen make my world a little less lonely. I can only imagine what it does for the small-town girl who doesn’t yet understand why she’s so different.

There is a sort of je ne sais quoi innate in butchness, an air and an energy that is both masculine and feminine and neither at the same time. In an imaginative sequence on One Mississippi, Tig and Kate sing a duet of “Ring of Keys” from the musical adaptation of Fun Home. The song touches on the spectrum of female masculinity that Tig inhabits, that I inhabit, that my closest friends inhabit, that Alison Bechdel wrote about, that Jeanine Tesori put into song — the image that is missing from mainstream media: the swagger and the bearing, and the just-right clothes you’re wearing, the short hair and the dungarees and the lace-up boots. And the ring of keys, a symbol for those of us who open doors and cross boundaries. ●