About five hours into the ESPN documentary O.J.: Made in America, which will air on the network this summer, journalist Celia Farber — one of dozens of friends, family members, police officers, lawyers, jurors, and civil rights activists interviewed for the film — articulates one of its central themes: “We talk about O.J. as if the story of O.J. is O.J.,” she says. “But the story is O.J. and us.”

Back in the mid-’90s, Simpson — and the wide-reaching ramifications of his trial — was impossible to avoid. But over the last five years, he’s receded in cultural memory; most people only vaguely remember that Simpson is once again in jail, for an offense too convoluted to remember. But in 2016, more than 20 years after Simpson’s acquittal of the murders of Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman, two productions are forcing Simpson back into the cultural conversation: The first, American Crime Story: The People vs. O.J. Simpson, will star Cuba Gooding Jr., air on FX, and focus on the trial itself.

The second — O.J.: Made in America — does something more ambitious. By situating the trial amid 50 years of abuse and distrust between police forces and the black community, O.J.: Made in America makes it impossible to think of the trial in a vacuum — as disarticulated from issues of race and masculinity, or as unconnected to the current tensions that structure the Black Lives Matter movement. “Everything,” director Ezra Edelman told me, “is about everything. [O.J.] is everything! It’s race, it’s class, it’s gender, it’s the criminal justice system, it’s the media, it’s sexuality, it’s all of these things.”

O.J.’s story is one of intersectionality: of a rich black man who disavowed his blackness, lived in an all-white neighborhood, was tried for the murder of his beautiful white wife, and was defended by a prominent black man before a jury composed mostly of middle- and lower-class black women. As one interviewee puts it, “If O.J. had killed [his first wife, who is black], this would not have been the trial of the century — and his black ass would be in jail.”

O.J.: Made in America opens as it closes, on the bleak Nevada landscape where Simpson is currently serving his 33-year sentence for armed burglary. From there, it cuts to Simpson’s recent parole hearing, in which a notably graying and ragged Simpson appears like a bloated doppelgänger of his trial-era self. He describes his time helping coach a team of “old guys” to prison football victory and chuckles, pulling out the charisma that made him one of the most indelible figures of the ’70s and ’80s. But the parole board is stone-faced: “In 1994, you were arrested at the age of 46?” Simpson fumbles with his answer, as if confused that anyone would need to confirm the year that he became the most infamous face in America.

It’s the only shot of contemporary Simpson we receive, but that image of Simpson — a shade of himself, dressed in a baggy, dark green prison uniform, yet still limply attempting to charm — hangs over the rest of the film, especially as the narrative flashes back to 1965 and the beginning of Simpson’s football career. Using beautifully digitized footage, the film provides the sort of background that even those who closely followed the trial might not have understood: a working-class San Francisco neighborhood where Simpson grew up; O.J.’s transfer from junior college to USC, one of the few universities that didn’t produce a student movement during the late ’60s, where he was treated as a demigod among an all-white student body; his early marriage to Marguerite, the high school girlfriend he “stole” from his best friend Al Cowlings; his gay father, about whom he never spoke, either publicly or with friends. All of this, according to Edelman, was pieced together to re-establish parts of Simpson’s past that had been elided by the spectacle of the trial. “You have to show him through this different lens,” Edelman told me. “That he was great. That he wasn’t just handsome — he was beautiful. That he was naturally charming and naturally magnetic. To actually have you understand, you have to be seduced by him.”

The archival footage is necessary to understand Simpson’s appeal, but you need a different sort of archival footage to contextualize the history of Los Angeles and how powerfully it would inform what happened to Simpson. Between 1940 and 1960, the black population of L.A. went up by a startling 600% — there was a notion that black people could come to California, obtain a middle-class lifestyle, and absent themselves from the history of race relations that plagued so much of the rest of the country. But incendiary footage, newspaper clips, and testimony from the time demonstrates just how hollow that promise was: L.A. might not have had segregated water fountains, but the racism, especially as enacted by the Los Angeles police department, was just as stark. Most know about the Watts Riots, but Made in America situates the riots within a pattern of policy abuse against which O.J., and his rise and fall, would take place.

Returning to footage of young Simpson, intercut with anecdotes from those who surrounded him, a portrait emerges of man determined to assert himself as “beyond” race. Simpson consciously refused to participate in efforts on the part of other black athletes to use their stature and power to speak out for civil rights — and disaffiliated himself entirely from the movement. He was, as one interviewee points out, a counter-revolutionary athlete: while Mohammad Ali and Jim Brown aimed to trouble the relationship between white sports fans and the black athletes they watched, Simpson smoothed it. “I’m not black, I’m O.J.” was his overarching philosophy: He truly believed his skill elevated him above questions of race.

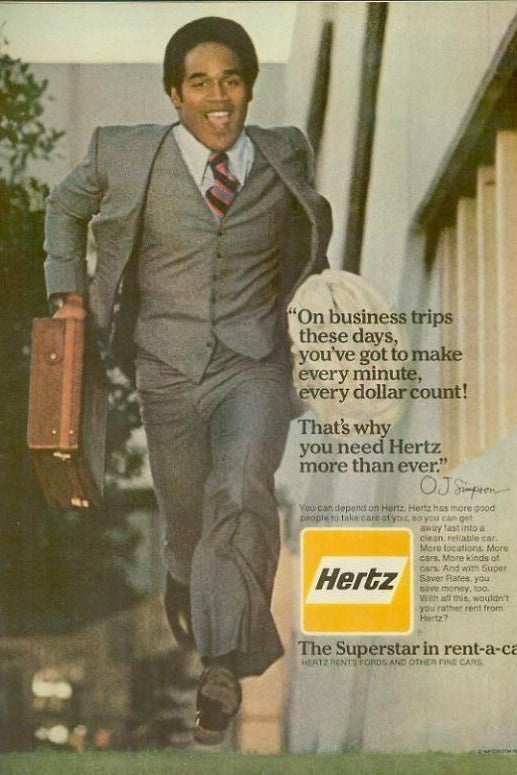

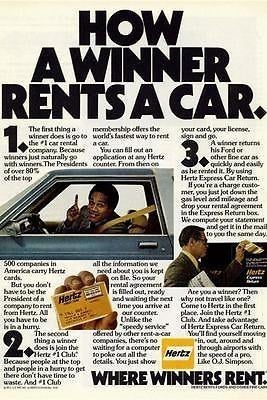

After Simpson’s miraculous 2,000-yard season as a member of the Buffalo Bills, he turned into a mix of Russell Wilson and Will Smith, incredibly humble, infectiously likable, and gifted with the sort of charisma that made him a natural fit to represent national brands like RC Cola and Hertz — the first black celebrity who could speak to consumers of all races.

Most documentaries would rely on a cultural critic to underline just what made Simpson so palatable, but Made in America goes for Mark Morris, a former advertising executive who developed the massive advertising campaign that would permanently align a sprinting Simpson with a car rental company, and Frank Olson, the longtime Hertz CEO who OK'd it. “For us,” Olson explains, “O.J. was colorless” — a viewpoint they perpetuated by carefully filling the background of every commercial entirely with people who were not black, as if the presence of another black man without his precisely calibrated image would somehow sully the product.

Made in America doesn’t treat the trial as any more crucial to understanding Simpson than the actions of the famously bigoted L.A. police chief Daryl Gates, Nicole Brown’s diaries and terrifying 911 calls, his friendships with legions of white businessmen, or accounts of Simpson’s status as a legendary cheater at golf. Indeed, we don’t even get to the Bronco chase and the hiring of the so-called Dream Team of lawyers until the end of the third episode — just over halfway through the five-episode series.

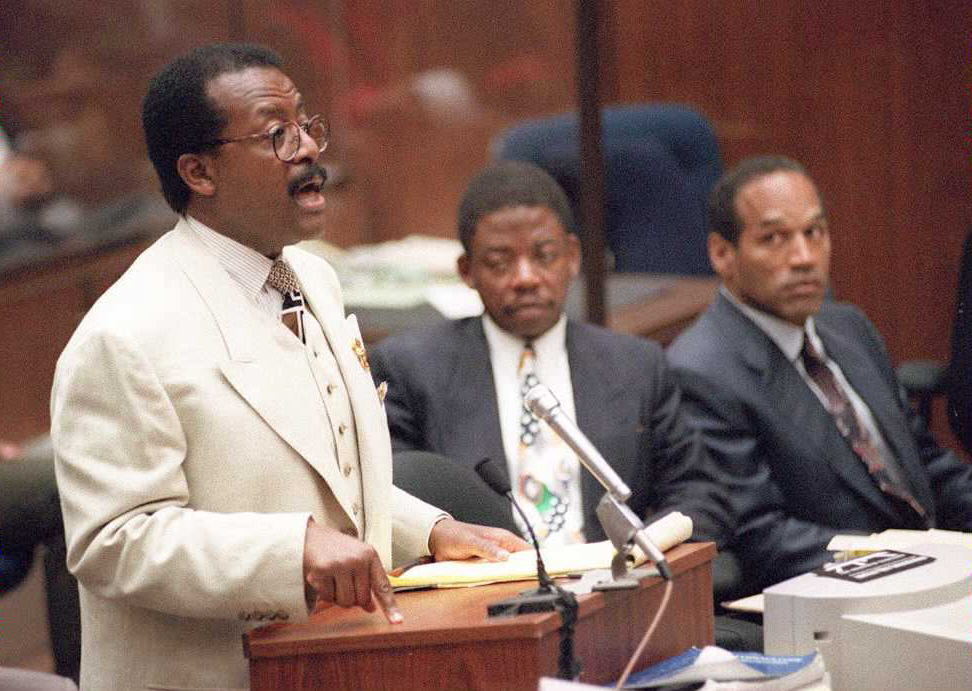

Yet, the fact that none of the information preceding the trial felt extraneous is a testament to Edelman’s ability to weave policy, commentary, and imagery in a way that always feels fluid and necessary: Of course we should spend 10 minutes learning about the death of Eula Love, who was shot by police after an altercation involving a $22 utility bill; of course that relates, however indirectly, to O.J.’s casting as a hapless, guileless dupe of a cop in Naked Gun, or to the snippets from Nicole’s diary in which she recounts all the times Simpson beat her, or the black-and-white footage of Johnnie Cochran's first trial, at the age of 26.

In this way, Made in America feels far less like a documentary with a driven narrative point and more like a societal tapestry — a characteristic of so many of ESPN’s 30 for 30 documentaries, which have proven that a sports story is also always already a culture story. Simpson thought that being a champion excluded him from messy identity politics: a belief that echoes those of so many fans who maintain that sports is, indeed, “just a game” and nothing to think about critically. But Simpson was at the very locus of race dynamics in America — he was operating so effectively, and invisibly, that it felt like he wasn't operating at all. To say that Simpson “didn’t care” about race is to ignore the ways in which he was constantly, obsessively, orienting himself within the empowered position of upper-class whiteness.

That obsessive orienting, however, meant simultaneously maintaining a certain class position, with accompanying cultural capital: He engaged in white extra circulars, hung pictures of himself with white people on his walls, and, most significantly, acquired a white wife. Essentially: He acquired white privilege. And it worked! That nexus of a very unique, powerful, yet nonthreatening masculinity not only seduced a wide circle of businessmen and Hollywood stars, but the vast majority of the consuming public.

The second half of the documentary does a thorough and damning job of showing how that image started to fall apart — while also showing just how effective Johnnie Cochrane was at being able to stop, or at least distract, from that unraveling. Not necessarily by proving Simpson innocent, but by inserting him into the long history of racial politics that punctuated the first half of the film — a history so potent, so viscerally and emotionally charged — Cochrane was able to trump all evidence of Simpson’s misogyny.

In essence, Made in America argues, Cochran made Simpson black again. And it was only by reasserting the politicized racial identity that Simpson had labored decades to leave behind — and presenting the racism of Mark Fuhrman as a vivid personification of years of abuse and neglect — that the jury, made up predominantly of black women, could so readily vote to acquit. Watching Made in America, their decision makes sense. It might have been, at least in part, compensation for the racially charged injustice of the Rodney King trial — but the jurors don’t seem stupid, or duped, but disenfranchised citizens exercising the little power they had.

The best documentaries make it impossible not to empathize with the subjects within. Despicable, beautiful, honorable, or broken, they nevertheless come across as undeniably human. The subject of O.J.: Made in America is not Simpson, at least not exactly — it’s also America, and the broken justice system and power differentials, so many of them rooted in race, class, and gender that surround them. The aim isn’t, then, to understand why Simpson was accused, but to understand why everyone — the jurors, the audience, the people who lined up to greet his car after he fled the police — acted the way they did when faced with the question of his guilt.

The version of Made in America that was screened for audiences at Sundance had a temporary score, large swaths of which were borrowed from Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. That film was, as its subtitle suggests, a requiem for a city that lives in the imagination of the world, but also a holistic indictment of the way a nation failed its most vulnerable citizens, those who reside in the disenfranchised intersection of race and class. It's the most powerful and essential documentary of modern America — and O.J. Simpson: Made in America is its equal and successor.