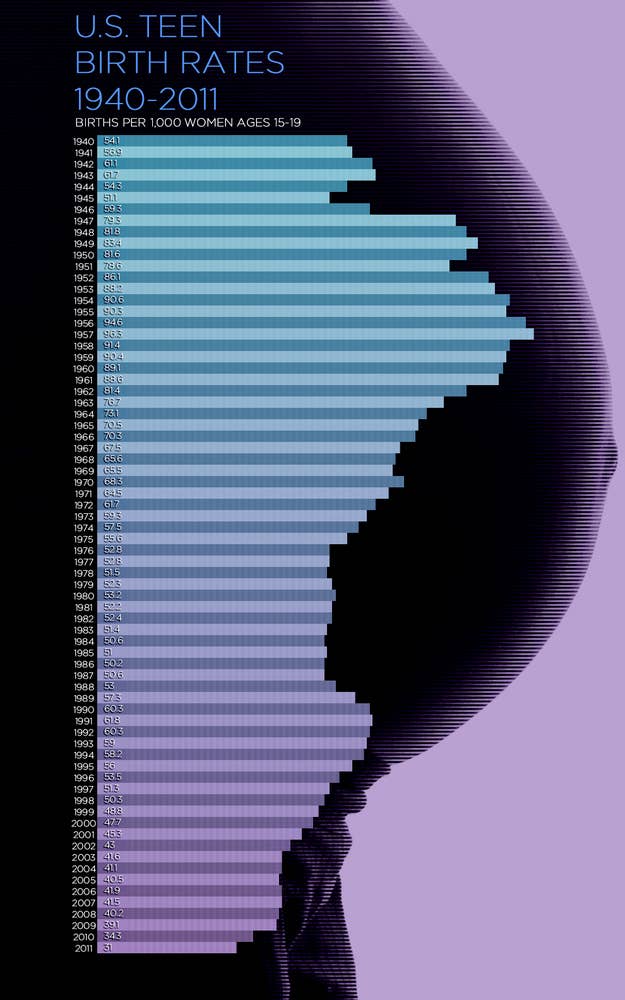

The teen birth rate in the U.S. is the lowest it's been in 70 years, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The year of 2011 saw about 330,000 teen births, which is 8 percent lower than the previous year and the lowest for a single year since 1946. The 2011 numbers also reveal that the overall downward trend in teen births that began in 1991 continues. While some economists think it's great that the teen birth rate continues to decline, they warn not to get too excited since the ailing economy seems like a likely cause — and the teen birth rate could start increasing once the labor market bounces back.

The University of Maryland's Associate Professor of Economics, Melissa Kearney, sees a correlation between "really high unemployment" and a lower teen birth rate. It's hard to pinpoint exactly why high unemployment would affect the birth rate for teens specifically, but she has some theories. "It's easier to think about a married couple in their thirties delaying child birth by a year or half a year," she told BuzzFeed Shift. "A lot of these teens are 18, 19 years old, and it's feasible that they might think it's harder for them to support a baby. It might be harder for them to get financial support from their parents if their parents are out of work."

Though research has come out linking declining teen birth rate to policy changes, Kearney says she and her research partner haven't found any recent ones that would explain the significant decades-long decline. "When we see these announcements that the teen birth rate is down, advocates like to attribute it to their policy" — like abstinence education or comprehensive sex ed in schools, for instance, she notes. But the only policy that matters for the teen birth rate, Kearney has found, is Medicaid benefits. "More and more girls can get family planning free through Medicaid even if they don't qualify for Medicaid insurance," she pointed out. And that reduces unplanned teen pregnancies, even though the effect is small.

Kearney finds connections between Obamacare and declining teen birth rates "absurd." "That's about requiring health insurance coverage to cover contraception, which is so different from expanding Medicaid," she notes. "If you take a middle income woman paying for contraception, if she has a copay and she pays her copay and now it's free, we're going to see no change in behavior. The reason we see a change in contraception use or behavior for poor teens is because they aren't paying for it for themselves."

Another way Kearney and her colleagues know policy isn't affecting the birth rate significantly is because the short-term steep decline and longterm slower decline aren't just U.S.-specific — the U.K. and Canada have seen similar patterns.

A paper co-authored by Kearney that came out earlier this year connected income inequality (between the poor and middle class, not the poor or middle class and highest income Americans) to high teen birth rates, especially in states like Texas, Misssissippi, and Minnesota where this gap is persistently large. But she says this is a different phenomenon from the declining birth rate across the country. And even though the birth rate is down for all Americans but teens in particular, the U.S. still has the one of the highest rates of teen births for a developed nation, which should remain a concern.