After 70 years of reservations for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, and 25 years of reservations for Other Backward Classes, a sizeable mass of educated, vocal Bahujans has emerged. These Bahujans are political, assertive of their identity, and are cleverly using platforms like Facebook and Twitter to talk about issues concerning them. I have been using social media for almost a decade now, and have been quite vocal about caste issues over the last two-three years. In this time, I have seen a pattern of how discussions around caste unfold. If the conversation is exclusively among Bahujans, a lot of nuanced arguments, informative tidbits, and insightful anecdotes are shared. But if it is a mixed crowd, with “Sharmaji Ka Betas” and “Chaturvedi Uncles” also participating, the discussion quickly slides into a “Who will say the most moronic thing” or a “Who will offer the most stereotypical response” competition.

If you feel frustrated like me, and think that engaging with these Sharmas and Chaturvedis is a waste of time, I offer you a list of some of the stereotypical (and nonsensical) arguments they put forth, and how you can counter them.

1. “Reservations suck!”

Whatever the discussion may be, the moment upper castes hear the word “caste”, they completely derail the conversation by trashing reservations, and describing how much harm this policy has apparently done to the country. The easiest way to identify them is to check whether they call themselves “general category” persons, because, well, keeping up with the era of post-truth, they are totally post-caste.

They don’t understand that the “general category” is not reserved for upper castes, and that general category seats are not meant exclusively for them. The truth is that Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe/Other Backward Class students can also claim those seats if they make the cut-off. Upper castes feel that if we must have a reservation policy, it should be based on economic criterion and not caste. But a purely economic criterion turns a blind eye towards social and educational inequality and marginalisation — a direct product of the Hindu caste system. The purpose of the reservation policy is to increase the representation of castes which had no presence in the country’s bureaucratic set-up and higher educational institutions so far. Most of the government’s welfare schemes — such as the Indira Awaas Yojana, National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, and Public Distribution System – are caste-agnostic. They take into account the Below Poverty Line list, in which a poor household from any caste finds representation.

The reason I am contrasting the reservation policy with the government’s welfare schemes is that government schemes are concerned with people’s basic needs such as food, housing, and livelihood. The purpose of reservations, however, is increased participation of marginalised communities in India’s democracy and governance.

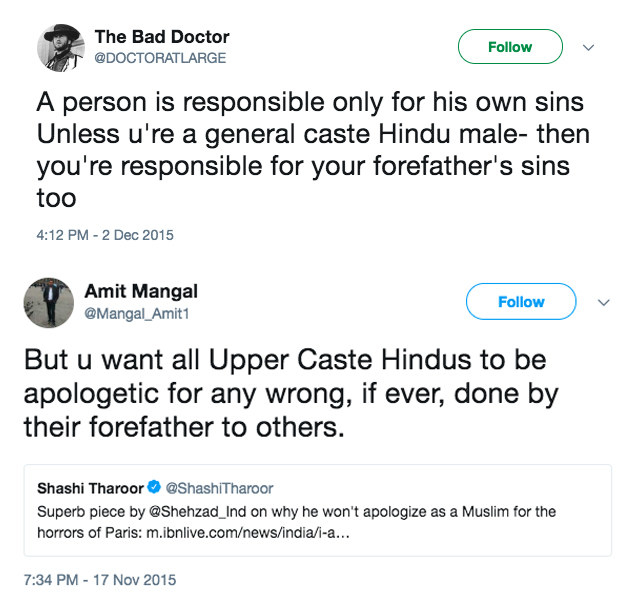

2. “You can’t blame us for the sins of our forefathers.”

If anybody points out Brahmin caste privilege, this is their stock response. They believe the reservation policy is a price they are unfairly paying on behalf of their ancestors. “Yes, our forefathers were bad and cruel. Yes, they codified and justified the caste system, subjugating Shudras and Ati-Shudras for centuries. Yes, they practiced untouchability and endogamy. But the fact is, caste system doesn’t exist anymore, so how can you say that we have caste privilege? Caste is a thing of the past, you know?”

The fact that your Brahmin identity is so unambiguously clear to you and others around you, is proof enough. Also, privilege is accumulated over generations, be it economic, cultural, or social. Caste privilege is the sum total of all your social, cultural, and economic privileges sedimented over generations. Therefore, you literally get a share of the “sins of your forefathers” when you’re born in an upper caste household. When someone points out your caste privilege, they don’t mean to make you feel guilty. They just want you to acknowledge that this world is unjust (and tilted in your favour), and we collectively need to do something about it.

3. “What privilege? It’s my hard work/talent.”

The moment you hint that the Dvijas (so-called twice borns) are better placed in life because they benefit from the caste system, they’ll probably start telling you about how much hard work they and their forefathers have put in over generations. Brahmins will gloat about their culture of “learning” unironically. Some shamelessly go to the extent of claiming that Brahmins have superior genes. Caste privilege? What is that?

A person’s hard work, talent, skills, and intelligence can coexist with their caste privilege. When someone says you benefited from your caste, it is not to say that you haven’t worked hard for the things you have got. It is not a comment on your individual characteristics. It’s just to make you understand that your hard work, talent, skills, and intelligence are of use only if you get an environment in which you can fully realise your potential. As it stands, that conducive environment is heavily skewed in the favour of Dvijas, as opposed to Shudras and Ati-Shudras.

4. “But Bahujans are casteist too.”

Whenever a finger is pointed at the privileges enjoyed by the Dvijas and their casteism, they are quick to point out how there is casteism among lower castes too. They will tell you how Bahujans also marry only within their own castes. References to caste violence perpetrated by peasant castes on Dalits are often made, and we are told about the hierarchical relationships between, say, Mahars-Matangs, Malas-Madigas, Pallars-Arunthathiyars, and so on, as if it’s new knowledge. The point is not that this is untrue. The point is that these arguments are strategically made by upper castes to deflect attention from their own complicity in the caste system, which benefits only them.

Discrimination is just one part of caste system, though an important one. The logic of the caste system is rooted in its material reality and material relations. If one intends to annihilate castes, one must attack the material forces that have kept the system intact. Pointing at casteism among Bahujans just to win an argument isn’t going to help.

5. “Caste is a thing that the British gave to India.”

This one takes the cake. The argument is that our society had Varnas, not castes, until the British arrived here, and that the Varnas were more like classes. It was the British who created castes by introducing it as a category in its census surveys. This claim is no less absurd than saying that caste is a Portuguese word and, hence, there are no castes in India. There is enough historical evidence now to prove that the caste system has existed for centuries, and predates not just the British, but also the Mughals.

6. “Caste is a thing of the past.”

“Yes, there was a caste system. Yes, society was divided in hundreds of castes. Yes, caste Hindus practised untouchability against the Dalits. But it’s not like we have any of that now. It’s not like we have Brahmin Matrimony and Baniya Matrimony to choose a ‘suitable’ spouse within our own caste. It’s not like untouchability is still practised. It’s not like Brahmin–Baniyas occupy most positions of power?

The caste system afflicts all social relations in India and has created a very unjust and unequal society. If we really wish annihilation of castes, we need to have a honest discussion around it. The first step towards solving a problem is acknowledging that the problem exists.