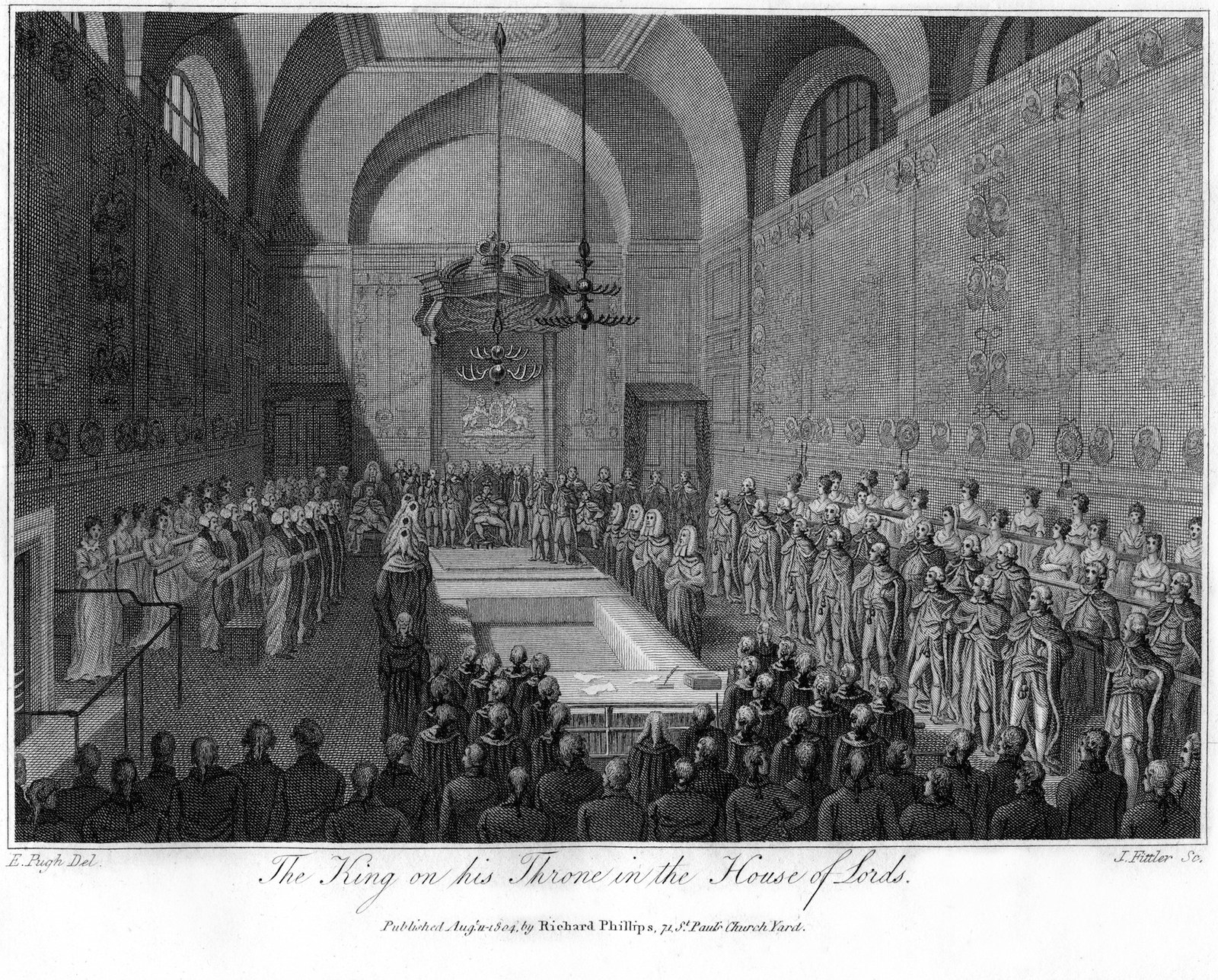

His father sat in the House of Lords, and his grandfather and great-grandfather before that. Now Hugh Somerleyton is hoping to win back his birthright, by standing as a candidate in one of Britain’s strangest elections.

Somerleyton, 45, is an aristocratic landowner, farmer, hotelier, and restaurateur. He was born Hugh Crossley. His ancestors made a fortune in the carpet trade. He grew up on a 5,000-acre estate on the Norfolk-Suffolk border, went to Eton, and as a boy served as the Queen’s page of honour, holding the monarch’s robes at state occasions. In 2012, when his father died, he became the 4th Baron Somerleyton, of Somerleyton in the County of Suffolk.

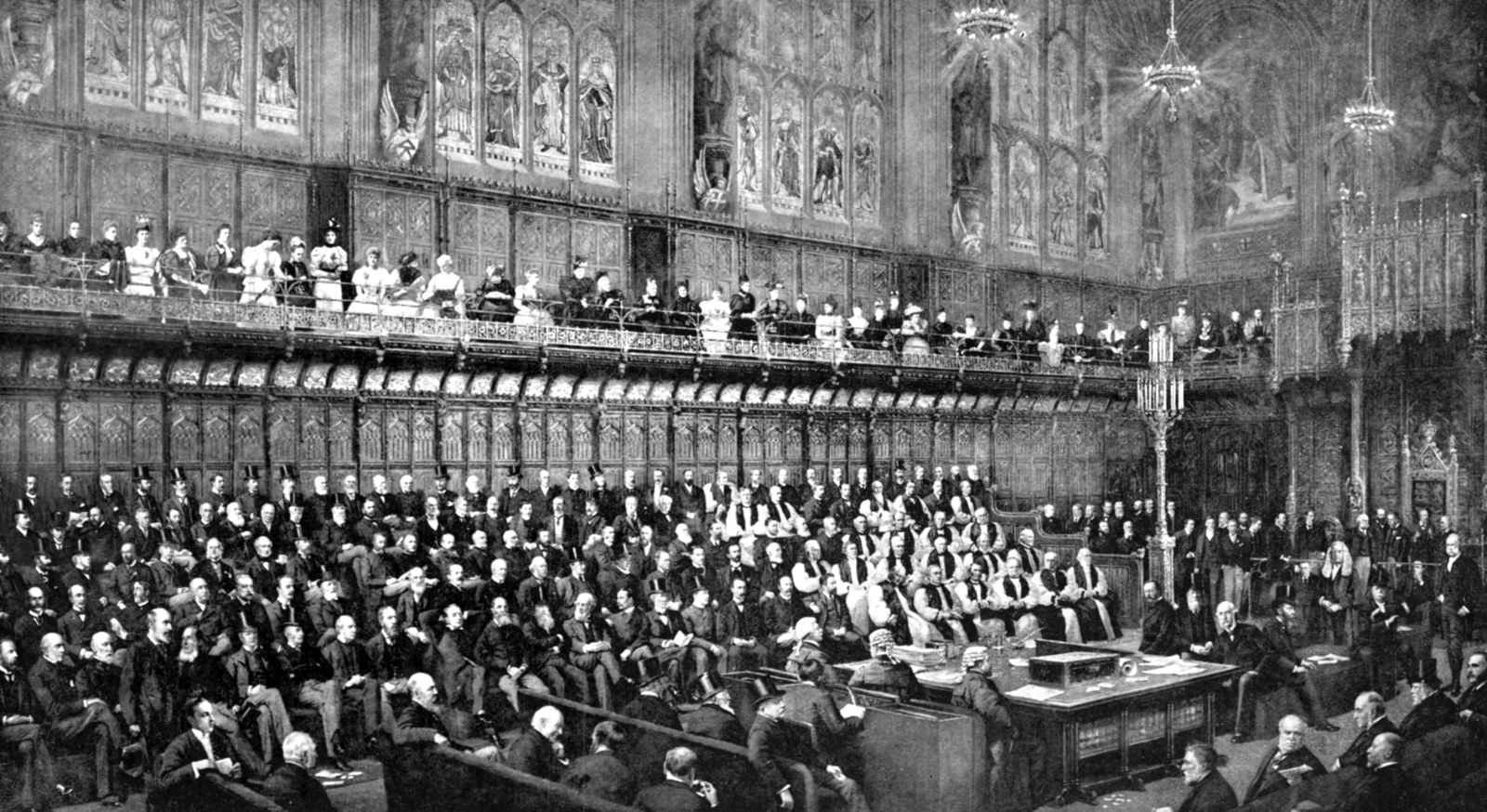

For hundreds of years, men like Somerleyton inherited seats in the House of Lords, as well as land and titles, when their fathers died. But in 1999, Tony Blair’s reforming New Labour government swept all but 90 hereditary peers out of the Lords in an attempt to make the house more democratically representative. From then on, most members would be appointed by the government, on their own merits. The Somerleytons, and many other noble families, lost their position in Westminster. (Another who was excluded was Christopher Guest, the actor and filmmaker behind Spinal Tap. He is the 5th Baron Haden-Guest.)

This week, Somerleyton has the chance to restore his family’s place in the House of Lords, through an obscure parliamentary by-election in which the voters and candidates are exclusively patrician.

A vacancy has arisen in the Lords because of the retirement last month of one of the remaining hereditary peers, a 79-year-old crossbencher — the term for members who are not affiliated to a political party — who was distantly related to Britain’s first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole. Under the reforms carried out by Labour 18 years ago, there is a bizarre mechanism for filling that vacancy: Hereditary peers of the same political affiliation are allowed to pick a replacement for the departed member, drawing from the pool of aristocrats who lost their seats in 1999, or their heirs.

This system of by-elections, little known outside small group of people in Westminster who tend to follow these things, is one of the weirdest quirks in an institution famous for weird quirks. It was a constitutional fudge, meant to last only until Labour could complete a second phase of reform — but that reform never happened. Its existence is a source of deep frustration and embarrassment to constitutional reformers and appointed members of the Lords, who believe hereditary succession should have no place in a modern democracy. That a tiny group of noblemen is allowed to award a seat for life in parliament to another nobleman is, to those critics, the most extreme illustration of an institution that is wildly out of touch with the people it is meant to serve.

“If this was a country in Africa, we’d be saying it was wrong,” said David Hanson, a Labour MP who was once Blair’s parliamentary private secretary and has campaigned to remove the remaining hereditary peers from the chamber. “The idea that a self-selecting oligarchy of people, who have been granted a place in parliament by virtue of their ancestors, can vote in another person to vote on issues that affect my constituents’ day-to-day lives is a complete nonsense.”

The by-elections are “the most ludicrous part of our constitutional setup,” said Darren Hughes, chief executive of the Electoral Reform Society, a campaign group.

And yet it is more than just a silly anachronism: The selected candidate will get the right to speak in debates and vote on laws. This is not a small thing when the Lords is more influential and important than it has been in years, and set to play a central role in the parliamentary debate about Brexit. The new member will get to have a say in the legislation that Theresa May needs to pass to lay the legal groundwork for leaving the European Union.

The vote is on Tuesday. Thirty-one crossbench hereditary peers are eligible to vote this time — men with titles like the Earl of Sandwich, the Viscount Colville of Culross, and Lord St John of Bletso. Somerleyton is competing against nine other candidates, who include a 32-year-old multimillionaire whose family owns a chunk of North Wales, a former senior Deutsche Bank executive who once testified to a parliamentary inquiry that the financial crisis wasn’t the fault of bankers, and a retired farmer who was once described by the Daily Mail as the “Council house Viscount” because he lived in public housing, his forebears’ fortune having long since vanished. “I wish to come and give my support for Brexit,” the Council house Viscount said in his candidate statement. “I have been in farming.”

Somerleyton sat under the Queen's golden throne in the House of Lords, watching men more than twice his age arguing about taking away his birthright.

It was 1999. Somerleyton was 28. He was, back then, one of Britain's richest young heirs, according to The Observer, standing to inherit a £25 million family fortune that included Somerleyton Hall, the stately home in Suffolk where he grew up. Somerleyton's great-grandfather, a Liberal Unionist politician, was awarded a peerage in 1916, which then passed to Somerleyton’s grandfather and, in 1959, to his father. His father, Sir Savile Crossley, was a farmer, philanthropist, former army captain and Master of the Horse to the Queen, who was described at his funeral as a “splendid English gentleman”. Somerleyton assumed that, one day, he would follow him into the Lords.

“I was looking forward to a life of service and contribution,” he told BuzzFeed News recently.

Then came Blair, with promises to make the chamber more meritocratic and representative of the British public.

As the debate about the future of hereditaries played out that year, Somerleyton went several times with his father to watch the Lords debating whether men like him should continue to sit among them. In November 1999, Labour succeeded in pushing through legislation that removed hundreds of hereditaries from the chamber, in one swoop. His birthright was gone.

“Obviously I was upset,” Somerleyton said. “To take it away is dismembering.”

Somerleyton fervently believed the politicians were making a mistake. The Lords wasn’t perfect, but it worked. It had worked for 1,000 years. He knew hereditary succession wasn’t logical. He knew people didn’t get it. “You’d be pushed to find a peer who’d try to argue that it’s a defensible system in the modern era,” he conceded. “Nobody would defend it. Except it's probably a better system than any other.”

The alternative, in his view, was worse. In a house where most of the peers were appointed, political parties would be free to stack it with “flunkies”. No longer would it be full of men like his father, measured and independent-minded with a loyalty to the history and traditions of the institution and an ingrained sense of public duty. It would be dominated by professional politicians, who owed their place in the chamber to the government of the day. It would be riven by partisan bickering. It would become like the US Senate.

The peers had capitulated too easily to the reformers, he thought. They should have fought harder to retain hereditary succession. “The House of Lords was a victim of its own decency,” Somerleyton said.

This is how the House of Lords is seen in the eyes of those who sit in it: as a vital part of British democracy that provides an important check on government power. It is eccentric and idiosyncratic, sure. You wouldn’t recreate it. But its near-800 members are mostly people of experience, expertise, and independent thought, who do much of the heavy lifting necessary to make good laws. It is a legislative “composting machine”, in the memorable phrasing of Michael Dobbs, the House of Cards author and Conservative peer, taking the crap sent over by the Commons and returning it months later smelling fresh.

This is how the House of Lords is seen in the eyes of constitutional reformers, the popular press, and many voters: as an undemocratic, elitist institution resistant to modernisation and bloated with mediocre time-servers and political cronies who do little to justify their £300-a-day taxpayer-funded allowances. It is a club for “doddering grandees who like a subsidised lunch and a warm place to snooze afterwards”, as The Sun described it, in a comment representative of much of the newspaper coverage of the institution.

Few things attract as much derision and exasperation among the Lords’ critics than the by-elections for hereditary peers. The failure of successive Labour and Conservative governments to finish the job that Blair started — to make the Lords either fully elected by the public or appointed by the government — meant that the elections have continued for nearly two decades. Twenty-nine peers have been elected to the Lords in this way, including Matt Ridley, the 5th Viscount Ridley, the Times columnist and former Northern Rock chairman, and Thomas Ashton, the 4th Baron Ashton of Hyde, a culture minister in Theresa May's government. All have been men, and roughly half went to Eton.

One who has stood in the elections, unsuccessfully, is Stephen Benn, the 3rd Viscount Benn of Stansgate. He is the brother of the Labour MP Hilary Benn and son of Tony Benn, the firebrand socialist. Tony Benn renounced the viscountcy he inherited from his father in the 1960s so that he could remain sitting in the Commons, but his eldest son took the title when Benn died in 2014, and now he wants to sit in the Lords as a Labour peer.

The by-elections have become a semi-regular event in British democracy, but still convey an air of amateurism — of gentlemen playing at electioneering. A case in point is the brief, often eccentric statements that candidates are asked to submit with their applications, which are published on the parliamentary website in the run-up to the vote. Candidates are given 75 words to set out their biography, political beliefs, and policy priorities. The submissions often given a sense of personalities that are as unreformed as the Lords itself.

In one election, David Russell, the 5th Baron Ampthill, a retired publisher who is married to the widow of a Russian royal, stated a long list of likes and dislikes, instead of giving his biography and political views. His likes included: understatement, rain, Hornblower, the law, Georgette Heyer, Spain. (Hornblower was a fictional naval commander. Georgette Heyer wrote romantic and detective fiction.) His dislikes: wind turbines, social media, quangocracy, fireworks, prejudice, bus lanes.

In another, Anthony Biddulph, the 5th Baron Biddulph, made this pitch to his fellow noblemen: “Older and wiser? Or never too late. Being a member of the House of Lords was always fascinating! It was an honour to serve.”

In another contest, Edmund Pery, the 7th Earl of Limerick, wrote a poem in support of his candidacy:

The Upper House knows none so queer

A creature as the Seatless Peer.

Flamingo-like he stands all day

With no support to hold his sway.

And waits with covert eagerness

For ninety-two to be one less.

In four of the elections, there were more candidates than voters. One election last year was seen as especially absurd.

It came about when Eric Lubbock, the 4th Baron Avebury, a Liberal Democrat, died. Because only hereditary peers of the same political affiliation are eligible to vote in the by-elections, the total pool of voters for Lubbock’s seat was limited to just three Lib Dems. Seven candidates registered to contest it. The winner was John Thurso, the 3rd Viscount Thurso, a former MP who lost to the Scottish National Party in 2015. When he was in the Commons, Thurso had argued that the Lords had lost credibility in the eyes of the public and needed modernising. But only months after being thrown out of parliament by voters, he was back, thanks to a weird constitutional loophole and the backing of only three party colleagues.

As a young man, Somerleyton bucked against family tradition. In 2003, ITV made a documentary about the Somerleytons, To the Manor Born, which portrayed Hugh as a profligate young toff with modern ideas that clashed with those of his staunchly traditional father. Instead of joining the army, as his father had, he went travelling in the Middle East. Then he moved to London, where he opened a couple of trendy Persian restaurants.

In 2004, however, the restaurants went out of business and Somerleyton moved back to Somerleyton Hall. His parents moved into a smaller house and handed over the running of the house to their only son. Somerleyton was in his early thirties.

The huge country manor, which has been in the family since 1861, was a “crumbling ruin” when Somerleyton moved back, but he began restoring it. He married his girlfriend, Lara, who he met in an art gallery in London, and they raised three children there (they're now aged 7, 5, and 3). They turned the estate into a healthy business, hosting weddings and private events and renting out the hall to rich tourists for thousands of pounds a night. They ran two pubs on the estate, opened the gardens to visitors, built holiday cottages around a lake, and farmed 2,000 acres. Somerleyton Hall has been featured in Tatler and the travel pages of several newspapers, and hosted the BBC's Antiques Roadshow.

Lately, with the business steady and his kids growing up, Somerleyton has been looking for new projects. A full-time manager has taken over the running of the estate, allowing Somerleyton to step back and devote more time to other things. One project he is trying to get off the ground is Hot Chip, an upmarket chip shop. He is looking for premises in London while testing the concept with a mobile stall at food markets. But Somerleyton has also been longing to do some kind of public service, he said.

A few years ago, Somerleyton flirted with the idea of becoming an MP in Norfolk and, for a while, got excited about the prospect. Many of his relatives, including his great-grandfather, had been MPs, and Somerleyton had causes he wanted to promote.

Some people, given Somerleyton's background, assumed he would run for the Conservatives. But he found a lot of the party's policies unappealing, too right-wing. “I’m not an out-and-out Tory,” he said.

If anything, he is an old-style Liberal, like his great-grandfather. He champions the countryside but has an environmentalist bent, advocating sustainable farming, replanting wild forests, and animal welfare. He believes strongly in statehood for Palestinians and the rights of refugees. And he is ardently in favour of Britain staying in the European Union.

On Brexit, Somerleyton said he understood why some people were frustrated with Brussels. He doesn't think those who voted to Leave were xenophobic, and he's not sure Brexit will be the economic disaster that some people make out. But he found it “mildly offensive” that Britain was turning its back on its European allies. "We're a better country for being in the union," he said. He didn't think it made him any less of a patriot for saying that.

Despite holding strong views, Somerleyton decided he didn't want to be an MP. Party politics wasn't for him, he decided. The reality of electoral politics was all a bit wearying and unattractive. “I missed the red blood cells that comes with being on either side of the political spectrum,” he said.

What he wanted instead, he decided, was to sit in the Lords as a crossbencher — an independent — as his father had. There, he would be able to make a sensible contribution to public life, without getting ground down by the rough-and-tumble of partisan politics.

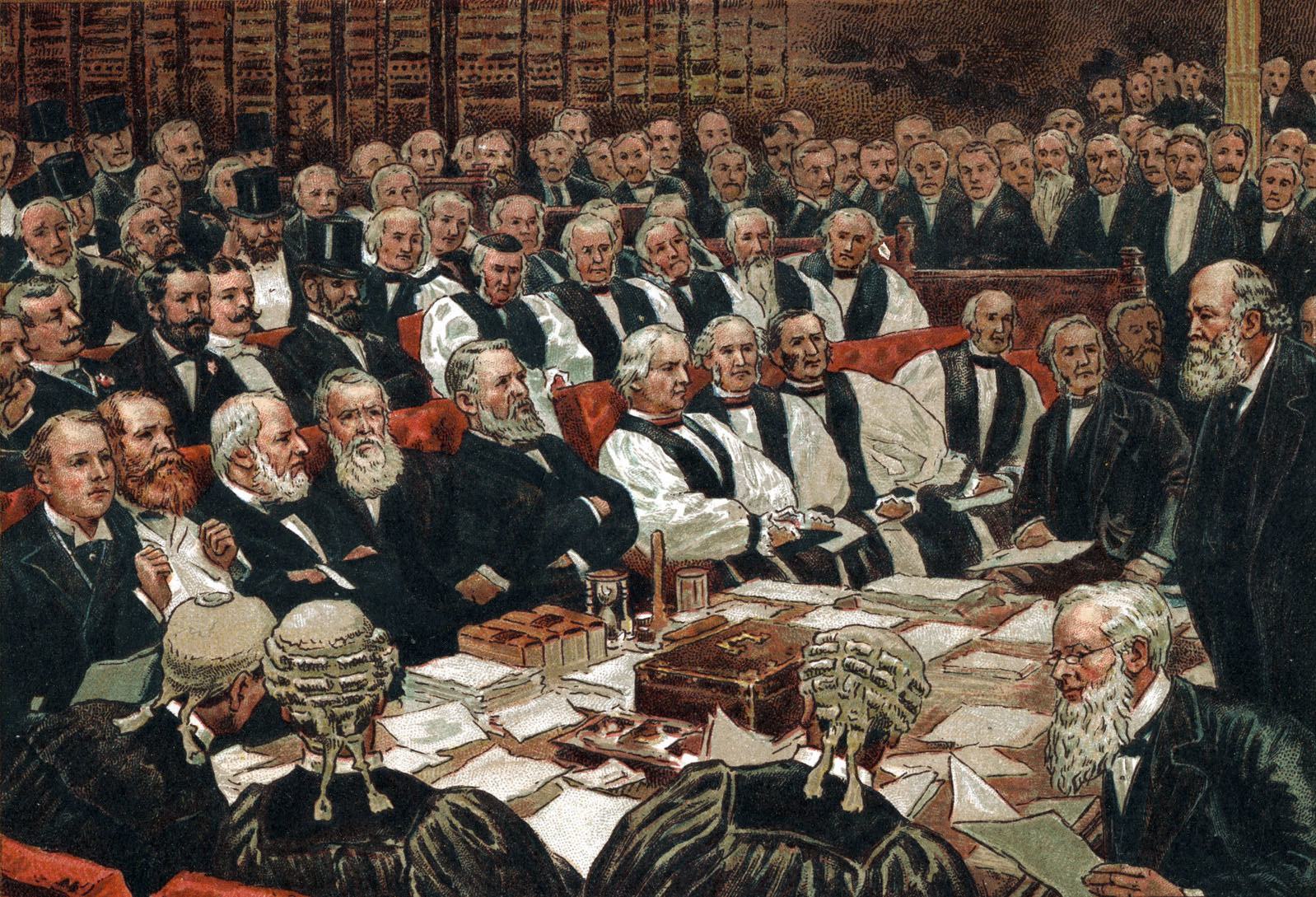

Last summer, a few days after Britain voted to leave the EU, Somerleyton was in a grand committee room in the Lords, waiting anxiously to make his pitch to a room of aristocrats who had the power to award him a seat in parliament. The aftershocks of the referendum were ripping through Westminster, shaking Britain’s political establishment to the core. It gave the proceedings, in Somerleyton's mind, even more of a sense of gravity.

A place in the Lords had opened when a hereditary peer was kicked out for not attending a session for a year. Somerleyton put his name forward to replace him, and now he was attending his first campaign hustings. He took a seat beneath two giant 19th-century frescoes depicting biblical scenes: Moses handing down the stone tablets from Mount Sinai, the judgment of Daniel. Somerleyton would have just a few minutes to make a case for himself.

Sitting opposite the electors, all elderly men of similar backgrounds, Somerleyton felt slightly intimidated. They seemed to be “eminent, very bright and learned men” who carried out their democratic responsibilities solemnly. This was not the ridiculous procedure depicted in the tabloids; these were serious men, here to make a serious choice at a moment of national crisis.

He glanced nervously at his speaking notes. This was nothing like campaigning in a typical British parliamentary by-election. There had been no canvassing or knocking on doors. Nobody handing out leaflets. Nobody wearing party rosettes. There were no journalists or TV cameras. Instead, there was just a quiet, polite, sober discussion carried out with a sense of “British calm and fair play”, as Somerleyton put it.

After the Brexit vote, the peers were looking to appoint someone with the sort of outlook and experience that would allow them to contribute to a detailed debate about the EU. Others in the running were more qualified to do that, Somerleyton thought. Clearly he was up against men who were smarter and had more relevant life experience. “If any of them get in I’d feel very reassured,” Somerleyton thought.

A week later, John Boyle, the 15th Earl of Cork and 15th Earl of Orrery, was elected. A former naval submarine commander, Boyle had, in a statement submitted with his application for the election, described his main concerns as the “continued attrition of the armed forces” and the “inherent dangers of Scottish independence”. His interests included “dendrology [the scientific study of trees], sailing, cathedrals”. He struck Somerleyton as having a brilliant mind and the sort of experience the country needed.

A few of the peers emailed Somerleyton after the hustings, thanking him for taking part. The general feeling was that he wasn’t quite ready. He was still, for the Lords, quite young. He would get other chances.

When parliament returned after the general election last month, a Labour peer laid before the Lords a private members' bill that would, if passed, abolish by-elections for hereditary peers.

Bruce Grocott, an appointed peer and former Labour MP who served as Tony Blair’s private parliamentary secretary from 1997 until 2001, is one of several Labour politicians across both houses who are determined to complete the reforms Blair started nearly two decades ago. In the last parliament, Grocott forced several debates on the subject, where he argued that the hereditary by-elections were “beyond ludicrous”.

The bill is not the first attempt by a Labour member to remove hereditaries, and it won't be the last. But it's unlikely to go anywhere in this session. Private members' bills almost never become law without the support of the government, and Theresa May almost certainly won't back it, according to peers and MPs.

In March, the prime minister appeared on course for a showdown with the Lords when peers pushed back against triggering Article 50, which started the formal process of withdrawing from the EU. Government advisers, ministers, and eurosceptic MPs made grave threats about abolishing the chamber if it became an obstacle to Brexit. Yet the prospect of an overhaul is off the table after a disastrous general election that left May's authority vastly diminished.

Even before the election, when May thought she was on track for a huge majority, her administration never really seemed to have the appetite for a fight with the Lords, despite the rhetoric about Brexit. Having seen her predecessors Blair and David Cameron get bogged down in messy constitutional fights, May didn't want to make the same mistake. Her campaign manifesto promised only to “continue to ensure the work of the House of Lords remains relevant and effective by addressing issues such as its size”.

Now May doesn't have the votes to take on the Lords even if she wanted to. Constitutional reform is not on Downing Street's radar. At least until there's a change of government, the hereditaries will keep their places in the Lords, and the by-elections will continue.

On Wednesday, the senior clerk in the House of Lords, dressed in a wig and black robe, will stand and announce to the chamber the name of the newest member of the UK parliament.

At home in Suffolk last week, Somerleyton was pondering his chances. As he looked over the list of candidates, he thought he had seen Charles Martyn-Hemphill, the Baron Hemphill, a fund manager, at a campaign hustings once. He seemed impressive. Richard Gilbey, the Lord Vaux of Harrowden, a corporate executive at a US technology company, finished runner-up in a previous by-election, and would surely be a strong contender again, Somerleyton figured.

Somerleyton wondered if he would still be seen as too young, too green. With Brexit coming, the Lords would need someone who could immediately contribute to deep, complex deliberations about legislation. He looked over his candidate statement and wondered if the wording was too lofty. It was hard to get your pitch across in 75 words.

Somerleyton had tinkered with the statement since the last time he stood, in March, and made a few changes to the wording. There was one thing he kept, though: a firm statement of his belief in the importance of hereditary peers. “In a time of great uncertainty,” he wrote, “its principle creates a sense of underrated commitment to the welfare of the nation.” You might find that strange, and Somerleyton wouldn’t disagree if you did. But don’t doubt that he believes it.