There’s a long pause while the network connects, and then finally my psychologist appears in a pop-up window on my laptop screen. It’s time for our first remote therapy session of the coronavirus era.

For nine months or so, the hour I’ve spent every Thursday afternoon in this therapist’s central London office has been the most important moment of my week. Now, both of us are in isolation at home — in my case, because a couple of colleagues are suspected of contracting the virus, although I’ve as yet had no symptoms — and there’s no alternative but to speak by video conference.

It’s a strange experience. I waste eight precious minutes waiting for the application to load and fiddling with microphone settings. The sound of drilling from building works next door provides a distracting backdrop.

There’s been a lot written in recent days about the importance of looking after your mental health in this chaotic situation. For even the most resilient of us, the spread of a deadly pandemic, the unprecedented disruption to daily life, and the extreme uncertainty about the future — all the things it feels like we’ve now lost — are deeply unsettling and stressful.

But it’s even more terrifying if you were already grappling with a mental health condition. Take it from me.

In the late 1990s, I was a 20-year-old in Auckland, New Zealand when I suffered a catastrophic, life-threatening episode of major depression. After a stint in hospital, I gradually recovered, started a career as a magazine journalist, and then moved to the other side of the world. Two decades after arriving in London, I’d made a good life: I had a happy marriage, a wonderful young daughter, a terrific job.

But then, at some point last year, I relapsed. There was no specific trigger, rather a series of stressful life events over a few years that, I eventually realised, collectively became overwhelming. This wasn’t the all-systems meltdown that I’d experienced as a young adult: I could muddle through every day well enough that most people around me didn’t notice. I never stopped being an attentive dad. I could still imagine a future. I wasn’t suicidal.

Even so, it was a miserable grind. I was constantly tired and despondent. My mind was totally scrambled. Confidence vanished. Small things began to seem like crushing obstacles. It was nearly impossible to concentrate. Some days I could barely complete an email. My work suffered.

As a political journalist, I should’ve been energised by the astonishing history-making events in Westminster, but instead I just felt drained and useless. I was guilty and anxious about leaving the battlefield, letting down colleagues, readers, and sources, but I kept that mainly to myself; it’s hard when you’re depressed to find the language to talk about it, even with the people closest to you.

Over several months, I got better. Put that down to a lot of painful work in therapy and some incremental lifestyle changes. I learned to meditate. I cut back on drinking (not easy given that, like too many in my trade, I’ve always used it to self-regulate) and stopped eating meat entirely. I tried to spend more time reading books, exercising and sleeping, and less on Twitter. I sought to avoid stress where I could.

At work, I was lucky to have a generous editor who gave me time to get back on my feet. My new goal every morning was to go into the office and focus solidly on one productive task for 20 minutes. If I could do that, I’d try another 20 minutes, and so on. We took it from there.

By the start of this month, I was feeling much stronger than I had six months earlier. I hadn’t recovered, exactly — there were still bad days — but I felt like I was slowly easing back into the life I want to be living. Winter would soon be over; I had some promising stories in the pipeline; we were planning a much-needed holiday.

Then came the outbreak.

Suddenly, my mind is a squall of doubts and anxieties. What will it be like to contract COVID-19? Will I infect someone else? Is my wife, who works in a public hospital, safe? What about our families and friends on the other side of the world? How will I keep doing my job and look after our daughter when her nursery is closed? Will I still have a job when all this is over? Will the health system survive this? Will the economy? Will anything ever be the same again? Where the fuck do I buy toilet paper?

Everyone is struggling with questions like these, of course. We’ve all been thrust into an appalling crisis that will be traumatic for anybody who endures it. But it’s especially daunting when you’re already emotionally depleted. And I’m worried about how I’ll cope over the next few months.

Now, in isolation, I can only see my therapist remotely. That’s helpful, but not the same as face-to-face contact. And I’ve been abruptly cut off from people, activities, and routines that I had come to depend on. For example: I’d gone into the office every day even when I felt dreadful, didn’t want to talk to anyone, and couldn’t produce anything, just so that I could maintain a sense of normalcy and wouldn’t be isolated at home. Remote conversations on BlueJeans and Slack don’t have quite the same stabilising effect.

So far, a week into quarantine, I’ve been managing fairly well, all things considered. The situation is so surreal that it hasn’t really sunk in yet. When you’re recovering from depression people often tell you to take each day as it comes, and right now that seems less a cliché than the only sustainable approach to living.

Try to find small routines to put your mind at ease, my therapist advised, and so the notepad next to my computer is scrawled with instructions like Read a book. Do a jigsaw puzzle. Meditate. Obvious, perhaps, but helpful so far.

But can I keep it up for weeks without sliding back? Months? I think so. I don’t know.

I’m not sure that my experience is terribly relevant or helpful, but it does make me attuned to what others who struggle with mental illness will be going through now. I’m far from alone. There are a lot of people in this position. And it’s crucial now that they’re not forgotten.

I’m thinking, for example, about the dozens of people in precarious circumstances that I’ve met through my reporting in the last few months. Many have serious mental health difficulties and were already, in various ways, socially isolated. I’m scared to think about how they’re going to be affected by the stress and uncertainty of the coming months — and whether they’ll be able to continue to access the support they need.

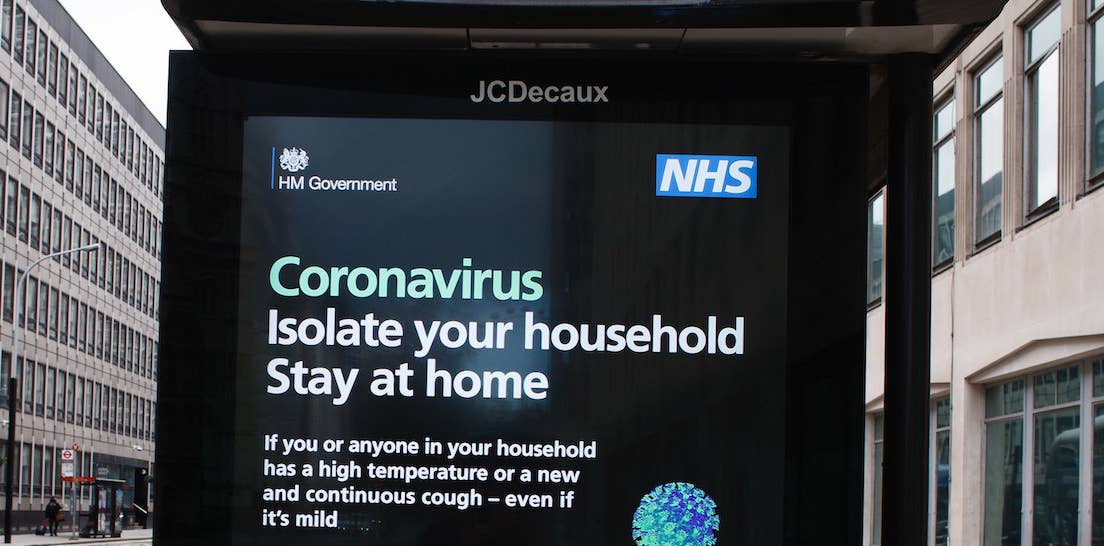

It’s difficult getting adequate treatment and assistance at the best of times, let alone in the midst of a national emergency that will push the NHS to the brink. There’ll be stories of real hardship in the coming months as people fall through the cracks. (I’m at alex.spence@buzzfeed.com, if you have a story you want to share.)

For now, I’m taking comfort in seeing how some communities are pulling together to support each other. This morning, while I was writing this, a leaflet dropped through our door from someone organising a local volunteer group to assist neighbours in isolation. I hope that continues. As this crisis drags on, a lot of vulnerable people are going to find it hard to keep going, and more than ever they’ll need to know they’re not alone. I know I will.