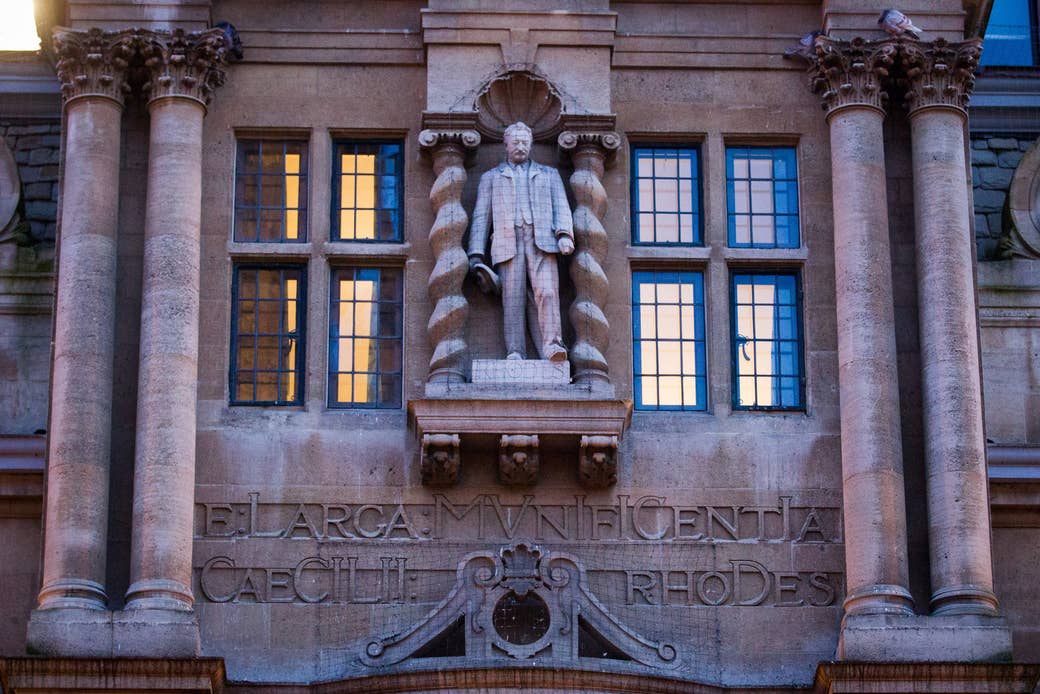

Somewhere along the line, the argument about the small statue of arch-colonialist Cecil Rhodes that has stood, barely remarked upon, 20 or so feet above Oxford’s High Street for just over 100 years became about freedom of speech.

A month ago, Stephen Pollard, the editor of the Jewish Chronicle, wrote a piece in The Telegraph subtitled: “If I … can tolerate the republication of Mein Kampf, then students at Oxford can put up with a statue.” Shortly after it was published, the Financial Times carried a piece about Rhodes Must Fall (RMF), the campaign for it to be removed, headed: “Student intolerance of ‘incorrect’ thinking imperils free speech”.

The debate has polarised the university, Rhodes' alma mater. On Tuesday a packed Oxford Union debating chamber voted 245–212 in favour of the motion “Must Rhodes Fall?”

At the event, the debating society provided a leaflet that said the campaign’s proponents "have been labelled hypocrites, revisionists and fascists; its opponents have been called colonialists, racists and white supremacists. … Bypassing the ad hominem attacks miring the debate at present, we want to address fundamental questions about the way our society works.”

But how did the threat to free speech become a clarion call for those who oppose the campaign? To understand that, we need to examine how Rhodes Must Fall came to prominence.

Protests at Oxford University are nothing new: Two months before Rhodes Must Fall grabbed headlines, there was a sit-in over the university's failure to decide about divesting funds from fossil fuels.

But this campaign had a catalyst that made it jump to the forefront of the public imagination and seize headlines in a way few, if any, protests at the university had before.

On 28 May 2015, the Oxford Union was hosting a debate about colonialism. The motion was: “This house believes Britain owes reparations to her former colonies.” On the night of the debate, the society advertised a “Colonial Comeback” cocktail, illustrated by a pair of black hands in chains. The image of the poster went viral, accompanied by the hashtag of the recently founded Rhodes Must Fall campaign.

Though the student-run debating society accepted full responsibility, the poster was, it seems, put up by bar staff rather than students. They were never named, and any disciplinary action taken against them was kept private for legal reasons.

The Rhodes Must Fall campaign would never have reached the prominence it did without the short, blowtorch-like intensity of the internet’s fury at this poster (along with corresponding anger from people claiming only those determined to take offence were outraged).

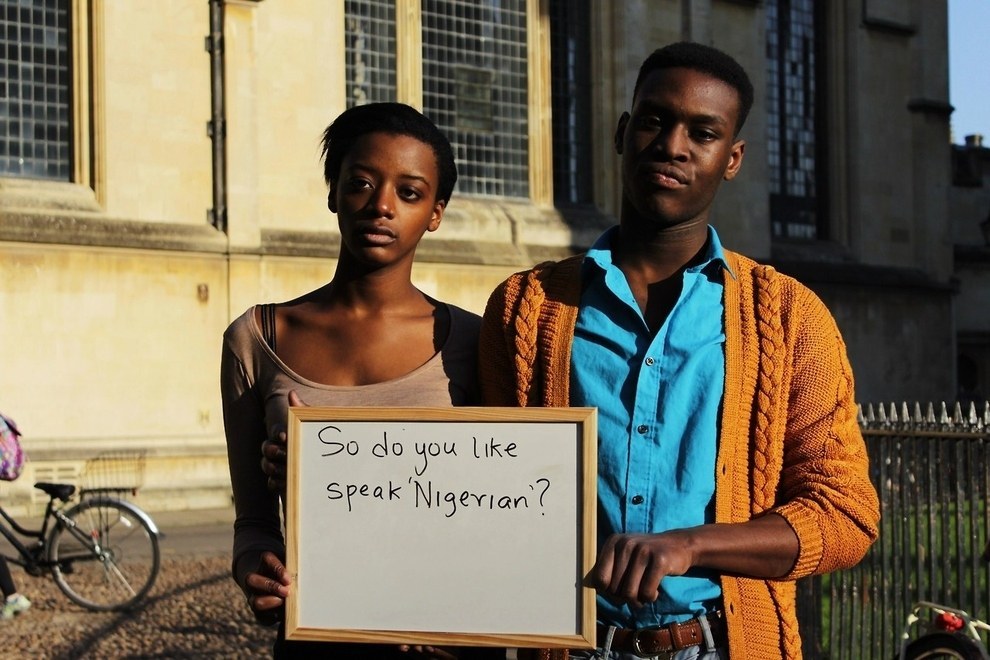

It became an emblem of the generally small but perpetual frustrations – aka microaggressions – many black and ethnic minority (BME) students said they felt on a regular basis at a university where they make up under 13% of the student population, as against 21% across all UK universities.

More and more testimony from BME students began to focus on a particular, rather British form of racism – one that was generally implied rather than overt. Victoria Princewill, a former undergraduate at Oxford, said:

I was subject to "jokes" that I was admitted on the basis of my minority status rather than my academic ability. I was repeatedly called "coloured", an outdated racist term, by one of my dearest friends. And on moving in with a black girl in my final year, I was asked if this was because we were both black, as opposed to simply being friends.

She added: “While individually minor, collectively these experiences have power; they tell me that I am not normal, I am an other, my experience is that of an other.” Elsewhere, Donald Brown – a black recipient of the university's Rhodes scholarship, founded after the colonialist's death in 1902 – described being mistaken for a construction worker by security staff.

Tadiwa Madenga, a master's student who has taken part in Rhodes Must Fall, told BuzzFeed News institutional racism takes many forms. She was at the university when the I, too, am Oxford campaign, which focused on microaggressions, took place, and said: "It's not a coincidence that campaigns like this take place in places where are these issues around iconography, because it's an institutional issue that should be taken seriously, rather than just saying 'here are some agitated students'."

She cited the university's curriculum: "You come to Oxford to be intellectually challenged, and you find yourself sitting there thinking, 'Did no one else contribute to this subject beyond these men?' If they're only giving me this framework, I see that as everyday racism."

The protesters have said, time and again, that their point is not about a chunk of stone, but what it stands for: lack of awareness of institutional racism. The statue is just another crass comment in a lecture, a mildly offensive costume at a party. Microaggressions. The kind of thing British manners suggest you shouldn’t kick up a stink about.

But suddenly people were. And this tendency was rushing head-on towards another that had been bubbling under since 2014.

In Spiked magazine’s 2016 project to rank universities on their commitment to free speech, Oxford is rated a “red”: It apparently “has banned and actively censored ideas on campus”.

Some of the examples the magazine cites seem dubious: Is a junior common room voting to condemn the song “Blurred Lines” three years ago a) still relevant, and b) actually an attack on free speech or rather an example of free speech and indeed democracy in action?

The magazine also claims Christ Church “banned” a debate on abortion, but actually the college told the organisers there wouldn’t be time to address “security and welfare issues” ahead of the debate, and they weren't able to find an alternative location in time. These details were largely left out or glossed over in national press reports.

But another action marked by Spiked seems more substantial: the banning by the Oxford University student union (OUSU) of a magazine called No Offence from being distributed at the university’s freshers’ fair in October 2015. No Offence was set up by a third-year philosophy, politics, and economics student at Exeter College called Jacob Williams and his friend Lulie Tanett.

The product of a Facebook discussion forum called Open Oxford, No Offence contained a piece arguing that the end of Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe – was “the end of a great country”, another that made reference to organising a mass “rape swagger” in the style of a “slut walk”, another with a description of an abortion, and so on.

Upon taking the decision not to allow the magazine, the student union said: “We at OUSU do not wish to have an event which is intended to welcome new students to Oxford associated with a publication making light of racism, sexual violence, and homophobia in an attempt at satire.” The controversy was covered across the national press.

When BuzzFeed News spoke to Williams about the magazine, he accepted it wasn’t a particularly intellectually stimulating publication, but denied that it was purely offensive for offensiveness’s sake.

He said he’d been influenced by Jonathan Haidt’s book The Righteous Mind, which argues that good people can be divided because “our minds are hardwired to be moralistic, judgmental and self-righteous”. That, Williams said, was why it was important to introduce people to potentially offensive ideas like defence of the anti-abortion argument or the view that Islam isn’t theologically peaceful.

And he was equivocal about whether OUSU’s decision to ban No Offence equated to an attack on free speech: “Yes and no. It’s their right, but it creates a climate of intolerance.” He also pointed out that he’d offered the student union the opportunity to remove any particularly offensive articles, but it hadn’t.

However, he said he saw the union’s decision to ban the magazine as part of a growing intolerance in the university, citing as other examples banners saying brutality shouldn’t be debated outside a debate on colonialism, the previously mentioned abortion debate, and the presence of “anarchists in balaclavas” when Marine Le Pen spoke at the university.

Jacob Williams outside Oriel, 16 January 2016 (left), and speakers at Oxford Union.

This brings us back to Rhodes Must Fall. Williams argued that the campaign was the latest incarnation of “an uncritical acceptance of sweeping condemnation of the values of the university". As a result, he has set up a Facebook group entitled Rhodes Must Not Fall. One of his arguments is that the campaign amounts to a form of censorship:

"It's a destructive approach, so they're saying that the culture is racist and should be reformed. It's very vague and there's no ability to create a positive culture – they can't say, 'Yes, Rhodes did things we wouldn't tolerate but it doesn't mean he isn't a part of our history.' Rather than a focused condemnation, they're trying to dismantle a culture that I think can be used positively. We don't have to tear things down to change the way things are now.”

The odd thing about Williams’ arguments is that in terms of the stated aims, there’s often barely a cigarette paper between them and those of the Rhodes Must Fall campaigners. Max Harris, a Rhodes scholar at All Souls College, told BuzzFeed News the campaign could be deemed a success precisely because it had brought issues of race and colonisation to the fore.

Both sides claim they want to represent a productive way of engaging with history. Williams said he didn’t believe the statue should be torn down, while Harris said the statue should be moved to a museum because “it’s hardly been a source of learning prior to the debate”.

Both said their positions aimed to cultivate a more rigorous understanding of history. Harris said the campaign aims to zoom in on things that happened and weren’t acknowledged. Williams complained about how history is taught in schools: "They should teach [colonialism]. The emphasis is on developing historical skills – you don't get a sense of the general course of British history."

Williams and Harris both condemn Rhodes, but Williams said the colonialist couldn’t be properly understood without nuance – that Africa was already a brutal place before he arrived and that his exploitation of it brought with it advances in infrastructure and medicine. Harris acknowledged this point, but said Rhodes was considered a problematic figure even in his own time and that this fact should be “laid on the table”, along with his engagement in military massacres, "proto apartheid", and so on.

Jacob Williams in central Oxford (left), the audience at the Oxford Union (centre), and Rhodes Must Fall coverage in the student press.

And ironically both were more comfortable talking about the issues surrounding the statue than the statue itself. If it should – or shouldn’t – come down, what of the other offensive historical figures around the city? Neither had a particularly convincing answer.

For Williams, it would be right to tear down a statue of Mussolini, because “Mussolini was linked to a specific regime. So it's right to tear [such a statue] down. There's a moral difference – Mussolini glorified violence and oppression, [whereas Rhodes' violence and oppression] was based on ignorance of other cultures.”

A questionable argument, but Harris’s answer – that Rhodes is a special case because of his combination of exploitation, military massacres, and proto apartheid – is no less debatable. Indeed, he said the major point was that Rhodes was a “strategic focal point” to start a broader debate for the campaign – which feels a little like having one’s cake and eating it.

Williams didn’t deny there was a problem with institutional racism, though on social media he seems more sceptical: “We need a more inclusive sense of identity – if people are being patronised that should be noted but I don’t think RMF is going about it in a sensible way.”

As Harris put it, the term microaggression “doesn’t seem so silly” when it’s taken to mean “a comment or an action that is harmful in itself but gains further impact because it recalls a pattern of oppression”. Putting these issues in a historical perspective, he felt, was far from censorship.

Madenga told BuzzFeed News that one key point made at the debate was the importance of not confusing free speech and public spaces – the former, she felt, was exactly what Rhodes Must Fall was exercising, in a bid to change the framework behind the latter.

And it’s on this issue that the movement has clearly won support within the university. On Tuesday hundreds of students discussed the matter and voted in favour of a motion that broadly suggested it was a problem and that the university needed to tackle it.

What will happen to the statue? Oriel College has announced a six-month “listening exercise” into its future. This week, University College passed a motion to change the name of the Rhodes Computer Room. There have been suggestions that the statue is protected by planning laws, but Harris, a lawyer himself, said the issue was “far from black and white”.

Last week, Lord Patten, Oxford University's chancellor, said the university should not rewrite history to pander to "contemporary views and prejudices", which Williams saw as an indication that "the tide is turning" and Harris felt was an example of the "kind of loose talk one hears about no-platforming". Madenga told BuzzFeed News that while discussing the issues was important, she hoped it would lead to Oriel making a decision on the statue one way or the other.

On Tuesday night a civilised debate was had over what that small lump of stone above the High Street really means. Which means that if free speech in Oxford University is being jeopardised, it’s being jeopardised in a very odd way indeed.