What is common amongst most First Nations People worldwide is storytelling. Stories passed down from generation to generation, used to teach about cultural beliefs, values, customs, history, practices, relationships and ways of life. A practise that is integral to First Nations People of “Australia”, like part of our DNA. Whether it’s singing at the Opera House, onstage at the theatre, or dancing ceremony on Country, it’s about telling our story.

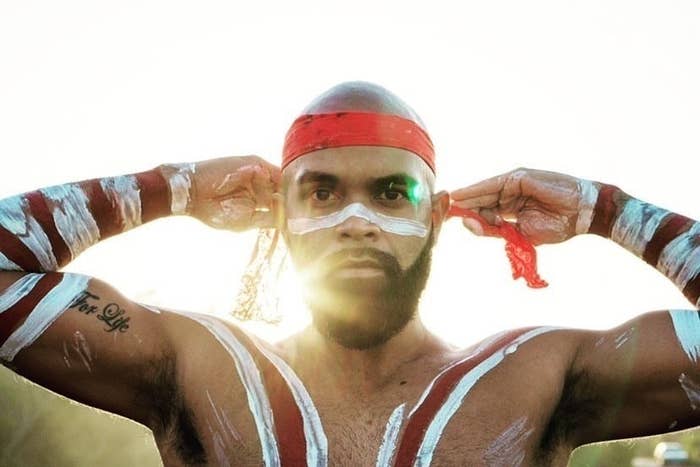

Storyteller Luke Currie Richardson, descendant of the Kuku Yalanji and Djabugay peoples, Mununjali and Butchulla Clan and the Meriam people of the Eastern Torres Strait Islands, explained to me: “When we are singing and dancing, we are performing for a reason. I don’t see my stuff as performing: I see my stuff as the continuation of song lines and culture. That's why I identify as a storyteller, not an artist.”

“I don’t see my stuff as performing: I see my stuff as the continuation of song lines and culture. That's why I identify as a storyteller, not an artist.”

Similar to Luke, in my experience, there is a link between performance and returning to Country. Country with a capitol C because it means more than the land you are on — it is a sense of identity. Country can be felt as a catalogue of connections that can re-affirm a relationship with Ancestors, Kin and language. As Lily Shearer, citizen of the Murrawarri Republic and Ngemba Nation Storyteller told me: “We (First Nations People) can dance that tree, paint that tree and sing that tree.”

“We (First Nations People) can dance that tree, paint that tree, and sing that tree.”

This idea of storytelling and interconnection is crucial in understanding Aboriginal identity. Past, present and future is one, the material and immaterial co-exist. We are not alone, we exist because we are made up of all that encompasses life — a simple and beautiful philosophy.

This means belonging and ‘home’ can always be remembered and felt. It could possibly explain why the Aboriginal culture of “Australia”, one of the most brutally displaced cultures on the planet, has been able to endure against all odds with strength and resilience. Kiarn Doyle, Dunghutti Storyteller and Bangarra Dancer, expressed it to me in the following way: "People don’t dance because they have to, it’s a drive. It’s hard to explain…Sometimes you can just watch people dance and there’s no story and it affects you. I think it’s because movement and music are the essence of life. Whether they’re non-Indigenous or Indigenous, I think people are looking for something to appease that yearning feeling for life.”

I believe that the yearning Kiarn talks about can be fulfilling, this is because it can open up a portal to knowing oneself. “Winhangadilinya”, in the language of the Wiradjuri people, is a feeling of knowing yourself. For many First Nations People, particularly when we are young, experience something of an identity crisis. This is because identity has always been dictated to us on a government and community level. For example, when I was in primary school, after explaining my mixed heritage to a classmate, she asked me, “I just don’t understand, why would your mum marry your Dad?” At the time, this confused me, and I asked her: “What do you mean?” and my classmate replied, “He’s just Black...and you’re not. Are you sure you’re Aboriginal?” Ever since then, I have always felt very aware of my identity.

This is a familiar story for many First Nations People of “Australia”, wrestling within the dynamics of a post-colonial society — although, what I experience in day-to-day life is nothing compared to what previous generations have experience. In my Dad’s case, he was a part of the Stolen Generation and was taken away as a young boy from his family and community. Fortunately, he always knew who he was, remaining strong in his own story. He explains he was one of the lucky ones, and through his strength, he passes on his story and cultural knowledge. Singing, dancing and acting became an escape for me away from the balancing act of juggling two worlds.

I look back on the history of NAIDOC Week and what my Ancestors went through to fight for our rights, life and land. Today, we want to heal. But the word healing for me is ambiguous because it denotes something’s broken. Instead, I believe healing equals strength in who you are, and storytelling creates a pathway for this to be re-affirmed. When we stamp or pick up the foot during a dance or ceremony, it is a physical call to wake up the earth, to wake up the mother, and to wake up Country, strengthening our connection.

Dalara Williams, Gumbaynggirr/Wiradjuri Storyteller, told me that when she is acting onstage, “We are carrying so much more than just ourselves in that space. You see that with religious experiences when people sing, they are singing about something bigger than themselves.”

"When we stamp or pick up the foot during a dance or ceremony it is a physical call to wake up the earth, to wake up the mother, and to wake up Country."

I believe acts of cultural revitalisation or expression often have little to do with the rejection of white Australia or remedying colonisation. In my opinion, they are about knowing who you are and re-defining a sense of identity. It is about owning your own narrative. When we fill our cultural waterhole, Winhanadiliinya is there. Dakota Feirer, Bundjalung Storyteller, revealed to me, “Performance is self-representation and the chance for us to self-define. It is empowering because in our culture, we have been performing our identities since the first sunrise; and the fact that it be a burgeoning remedy at the forefront of our self-determination is of no surprise to me at all.”

The expression of culture is active and alive in many forms, imitating the pulsating presence of the land. The notion that self-determination through storytelling is remedial, creates a strength for First Nations Peoples even within white institutions. Wiradjuri and Yuin Storyteller Angeline Penrith explained about acting within these spaces, "We should do it for ourselves, you know what I mean? 'Cause whenever we are trying to do it for the white man, we will always be damaging ourselves. 'Cause that’s not our fulfilment. We’ve lost so much as Aboriginal people and we want it back. In all mediums — old, new, whatever. We evolve like everyone else.”

"Whenever we are trying to do it for the white man, we will always be damaging ourselves."

Healing is strength, it is the act of self-love, self-determination and sharing knowledge that can be united through storytelling. Healing is also a shared responsibility, which can be the catalyst for change. After all, it is a shared history for all Australians, and many First Nations People want to share this gift of understanding about who we are as people. Perhaps this NAIDOC week is a call for a national Winhangadilinya, a collective healing and knowing of the self through whatever expression. So, be strong in who you are, and do you.

Akala Newman (she/her) is a Wiradjuri/ Gadigal woman, a Singer-Songwriter and an Assistant Producer at Moogahlin Performing Arts. She is also a Research Assistant (TPS) at UNSW, an Artist Educator at the Museum of Contemporary Arts and an Intimacy Coordinator at Key Intimate Scenes Australia.

Akala acknowledges the Ancestors of the unceded lands and waters, their spirit still walk among us, and pay respects to Elders past, present and future.