Ibrahim finds us as we walk back towards the entrance of Calais’ infamous migrant camp, nicknamed the "Jungle" by those inside. It’s the last week of evictions of refugees and migrants and there has been a heavy armed police presence, with 700 journalists descending on the camp trying to capture every moment.

Ibrahim checks our press passes, asks who we are, asks what kind of story we intend to write. Like everyone in the camp, he’s weary of exploitative journalists looking to use the camp’s inhabitants for their own political purposes.

“I know everybody in the Jungle, I know how life is going on here … for a long time,” Ibrahim, who doesn’t offer a last name, tells BuzzFeed News. With the well-honed cadence of someone who has clearly had a conversation several times in a row, he rattles off the different news outlets he’s had walked through camp this week.

Ibrahim’s got his own agenda. For him, it’s not just about letting the world know what’s happening in the Jungle – he’s passionate about how migrants and refugees are being treated across Europe, especially in Germany, where he lived prior to his time in Calais. His relationship with the Jungle is complicated. He says he’s been in Calais for years, since the camp first opened. And with eviction looming, he’s one of many we meet there who say they won’t be leaving.

“I will be the last one to leave the Jungle,” he says.

“I’m homeless but I’m not hopeless," he adds. "I want to be here. … No one can move me from here. No one can move me. I will be here.”

Ibrahim, who says his dream is to go to Canada, says he was a dentist in Sudan. Like many people at the camp, he made a long and difficult journey to get to Europe and has been in camps like this for four years. It’s a message daubed on some of the tents around us – that its inhabitants will stay despite the camp getting smaller by the day.

“It seems to be horrible because no one knows what’s going on. People seem to be running out of the Jungle, coming and going – I don’t understand anything,” he says, referring to the confusion engendered by the transportation of some 4,000 people out of the camp to shelters across France.

Ibrahim says he has to leave. It's getting dark and the mood in camp is shifting. As we leave, we pass the wreckage left by migrants and refugees boarding the coach buses: Smashed-up storefronts, trashed tents, and scorched portable toilets. Still-active bonfires send globs of black of smoke high into the air. It's all part of one organised and volatile message of defiance. They want to be the ones to demolish their own homes. Plus, it's a good way to let the French government know how they feel about the place.

Aid workers, standing by the Banksy mural of Steve Jobs at the camp entrance, say that in some cases people were going back and forth from the camp. They had already queued up and registered three times, been told to go back to the warehouse in the afternoon, and yet still did not know when they would be leaving.

We bump into Ibrahim the next day. He's chatting to aid workers at the top of the path heading to camp. He's on his way to walk a friend to the bus queue at the end of the street. The morning has a weird mood to it, a mix of confusion, fear, and hope.

At midday, he agrees to take us to where he's been living in the Jungle. We follow him through the camp's labyrinthine pathways as its residents pull more and more of the camp apart, lighting it aflame.

He says people navigate their way through the camp using landmarks such as a kitchen or a mosque. At the beginning he lived in a tent, but now he lives in what he calls a "room". It is a cube structure covered in green tarpaulin. The blue sleeping bag acting as a door is thick with rainwater. “It’s a bit dark, I can’t see very well," he says. "I don’t have a window."

On the floor next to his bedding is a paperback book: Last Man in Tower by the Indian novelist Aravind Adiga. He does not have many other belongings. He says most of the things members of the camp have come from aid workers or care packages friends and family are able to get into the camp. He was given his phone by a volunteer from England.

His neighbours included a Syrian man, and next to him an Afghani man and on the other side, another man from Sudan. Nearby was the Ashram kitchen. “Everyone knows it, everyone had breakfast there,” Ibrahim says. It closed two days prior. On Tuesday this week, when he woke up for morning prayers at one of the five makeshift mosques at the camp, fewer of his friends and the people he knew were there.

“All of the people are gone," he says. "Every day people are missing. and yesterday in the evening. You don’t see [many] people.”

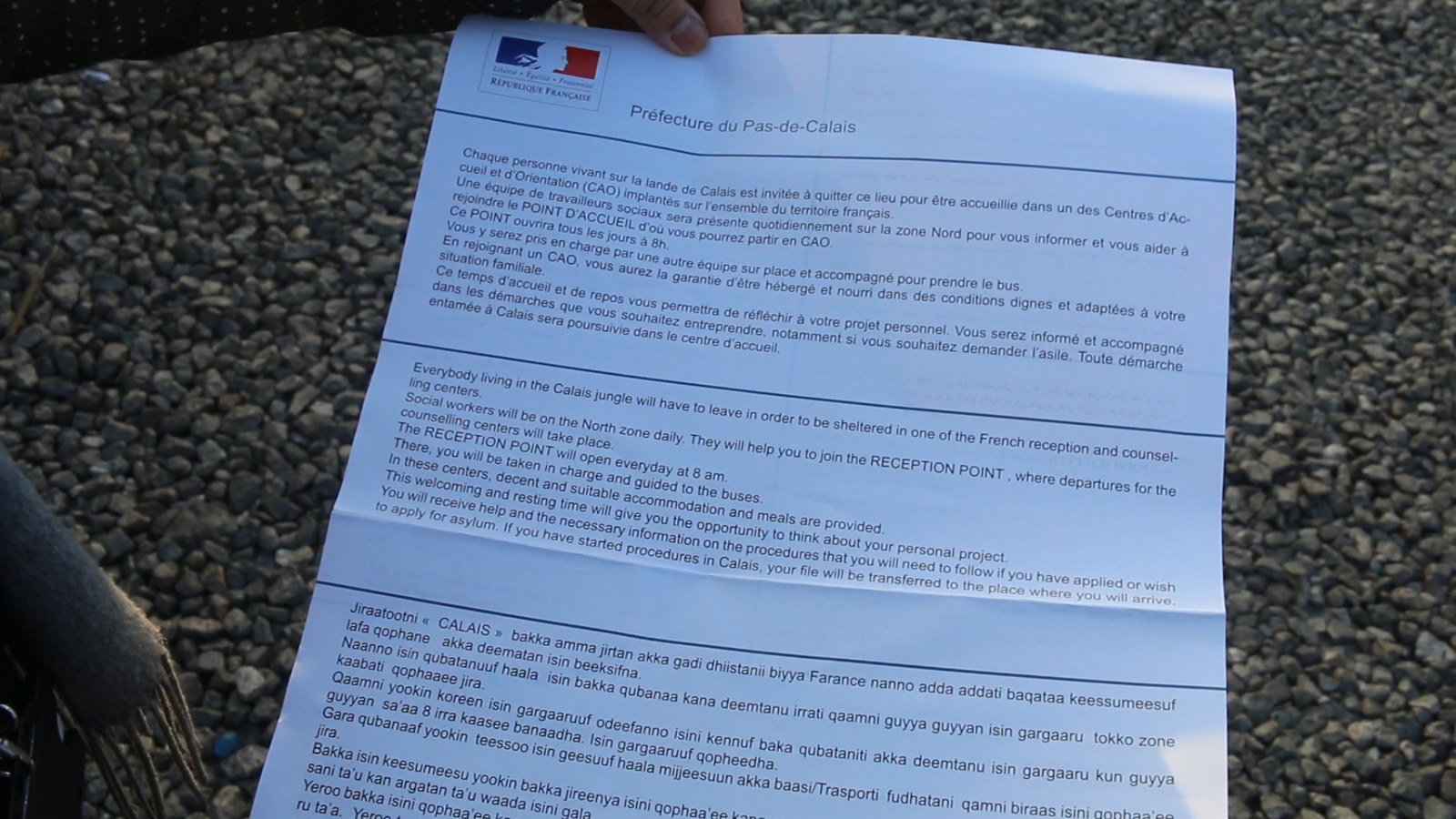

Walking through the camp, it's noticeably quieter, while French officials in red jackets hand out notices printed in multiple languages saying the reception point opens daily at 8am, describing the reception centres refugees and migrants are being sent to around France as "decent and suitable accommodation”, and adding that it will be an “opportunity to think about your personal project”.

Ibrahim says he "looked out" for 150 other Sudanese men in the Jungle. Of course, the line between the camp's smaller communities and the crime gangs inhabitants refer to as "alibabas" can be murky, like everything else in the Jungle, where conflicting realities are forced to exist at the same time. In the words of the UK's shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper, the camp is full of young men who are "easy prey for criminal and trafficking gangs".

After we speak to Ibrahim, a journalist messages us on social media, warning us to be careful around Ibrahim, claiming he's dangerous, that he threatened a news crew. We witnessed such scenes several times going through camp – a reporter would cross a boundary with a camp member and things would erupt.

While with us, Ibrahim's mood darkens. He grows anxious, and loses his train of thought, particularly when asked about what the future had in store for him. He only reaffirms that he'll be the last man standing.

“When I came to Europe, I slept in the street. It’s too cold, very cold, and this is not the first time here. I don’t care.”

It makes no difference to Ibrahim, and when asked what will happen on Friday, the last day of eviction, he says: “I will be the last one to leave the Jungle. I am Ibrahim. I was born in Darfur. And since 2011 been living in Europe and still living in this fucking situation. I don’t care.”