For 11 years, Babar Ahmad would break his Ramadan fast alone in his prison cell. An insulated steel container of curry would sit at his desk for hours, which he would eat after a long day of fasting. Afterwards, he would pray long into the night.

But eating iftar – the meal that breaks the fast – behind bars is now just a memory for Ahmad, who became the longest-serving British prisoner in modern history to be detained without trial in the UK.

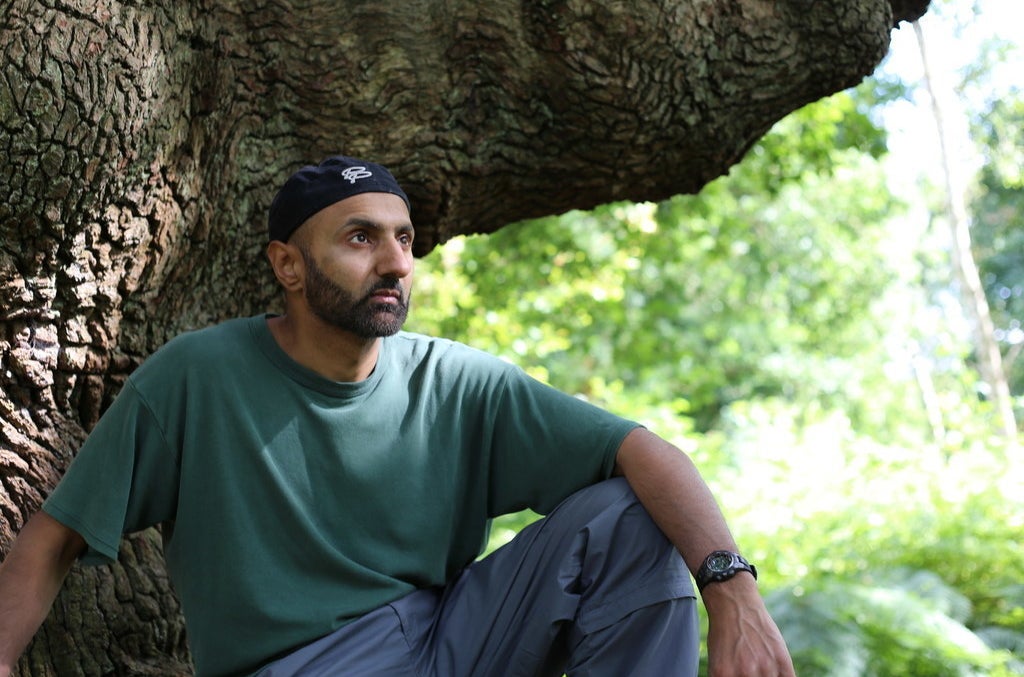

“In one way, it feels as if I am experiencing Ramadan in the community for the first time,” the 42-year-old former IT worker from Tooting, south London, tells BuzzFeed News, having spent Ramadan surrounded by family following more than a decade of imprisonment.

“Maybe I am experiencing all the emotions and excitement that new Muslims feel when they experience Ramadan for the first time. It is extra special for my family, especially my parents. For many years, they would feel my absence at the table during iftar time,” he says.

“In prison, the thing I missed the most about fasting was the sense of community. Breaking fast alone in your cell was still satisfying but not the same as breaking it with your loved ones at home, or with members of the community at a local mosque. I also missed attending Tarawih prayers in congregation."

Ahmad's was a high-profile case and a complicated one. He was arrested in 2004, pending extradition to the US to face accusations of supporting the Taliban through a website he set up in the '90s. Though the site operated from the UK, the US claimed jurisdiction because one of the host servers was in the state of Connecticut.

For eight years Ahmad fought extradition while held at high-security prisons across Britain. In 2012, he was moved to a US supermax prison after his bid to be tried in the UK, backed by a petition of over 140,000 people as well as celebrities and MPs, failed.

A year later, Ahmad accepted a plea deal and admitted providing material support to terrorists. US federal judge Janet Hall handed him a 12 and a half year sentence, describing him as a “good person” whom she believed posed no threat to the public. By 2015, because of time served, he was free to return home to the UK.

In the first interview after his release, Ahmad told the BBC his support for the Taliban was "naive" and that he had no idea of the terrorist attacks those living under the regime would go on to commit.

Ahmad, who is now writing a book and has been documenting his experiences of prison on his blog, wrote how he had “yearned and prayed” to be reunited with his family. At times, he says, he feared it would never happen.

“In prison, the thing I missed the most about fasting was the sense of community."

Over the course of 11 years, Ahmad spent time in 10 different prisons in both the UK and US, and says that the "one common thing was that the cell door was always closed at night. Therefore, for 11 years I ate suhoor [the pre-fast meal] on my own".

In the UK, prisons provided a suhoor pack consisting of milk and a small portion of cereal. As Ahmad had an electric kettle in his cell, he was able to boil water to make porridge, but in the US made do with warm water from the tap. "Doesn't taste great," he adds.

“As for iftar, in most of the prisons I went to, I had to break fast by myself, alone in my cell,” Ahmad says. "For some strange reason, most of the time the UK Ramadan food consisted of curry, a bit like halal food on airlines.

"With time," he says, "we explained to the prison authorities that most Muslims – in general and in prison in particular – were not from south Asia, so we were able to get them to vary the menu to cater for also white, black, and Arab Muslim prisoners.”

"By the time you broke your fast four hours later, the bland food would be stone cold, but it would still taste delicious."

US prisons were not as accommodating. “In the US supermax prison in Connecticut, a small quantity of food would be given to all prisoners, whether fasting or not, in a polystyrene box through a slot in the door at 4:30pm. By the time you [broke] your fast four hours later, the bland food would be stone cold, but it would still taste delicious."

Despite the isolation, Ahmad recalls one standout moment he spent at HMP Long Lartin, while in a small unit with six other Muslim detainees. Although they would all do their night prayers individually “every Ramadan night one would hear a chorus of the seven different detainees, from seven different nationalities, reciting the Qur'an during Tarawih prayers".

“It sounded beautiful," he says. "Even though our bodies were separate, our hearts were not.”

Ahmad remembers how some devout Muslim detainees would compete against one another to perform extra good deeds during Ramadan: “I remember one Ramadan, one detainee completed [reading] the Qur’an 10 times.”

In UK prisons where he was able to interact with other prisoners there was a sense of community among the fasting Muslims, who were generous to one another. “Before iftar time you would come into your cell to find bars of chocolate, packets of crisps, and drinks left for you that other Muslim prisoners had bought for you from their weekly 'canteen' spending allowance,” says Ahmad.

"You feel hungry in the day, but once you have opened your fast you have no memories of the pangs of the hunger that you felt only a few hours ago."

A spokesperson for the Prison Service told BuzzFeed News it was committed to ensuring that prisoners from all religious faiths are given the opportunity to practise their religion. Over 14% of the prison population are Muslim.

"There is a clear policy in place which states that as Ramadan progresses, appropriate arrangements should be put in place to support observant prisoners," the spokesperson said.

This includes providing suitable meals and allowing prisoners to celebrate Eid with congregational prayers and the celebratory communal sharing of food.

Ahmad says there are a few things he misses about spending Ramadan in prison, such as the time spent reciting the Qu'ran alone in his cell and the “solitude of being alone with Allah”.

Today Ahmad, who was awarded £60,000 as compensation after sustaining 73 injuries when he was first arrested by the Met police at his home, is reflective when he speaks of his experiences.

"It takes energy to hate and be angry," he says. "Instead of using up my energy to hate those who did wrong to me, I have chosen to use my energy to remember those who were good to me. I think the Muslim community in Britain is fed up with being defined by its victimhood when it has so much more to offer society."

He says there is a central lesson to take away from fasting during Ramadan, and draws a parallel to any hardship humans face in their lives: "You feel hungry in the day, but once you have opened your fast you have no memories of the pangs of the hunger that you felt only a few hours ago.

"In the same way, all hardships and suffering in life one day come to an end, and when they do, you can choose not to hold on to the negative memories of the pain that you experienced, but instead focus on how richer your life became as a result of that suffering."

For Ahmad, Ramadan has gained new meaning. “When you suffer as a result of something, it becomes dearer to your heart," he says. "Having experienced Ramadan alone in prison for many years, Ramadan is much more special for me now that I am out in the community, all praise be to Allah."