The cascade of love and appreciation for Roger Ebert after his sad passing had me misting up at my desk for hours yesterday. Ebert is one of the reasons I pursued a career in the wacky world of entertainment journalism, and to see how many people were also affected by him — from Steven Spielberg and Barack Obama to friends on Facebook — made sharing in his loss a little easier.

But that massive outpouring also took me by surprise. It wasn't that I thought Ebert was in any way undeserving; it's that I had long since abandoned the idea that a film critic could cast such a formidable and beloved shadow.

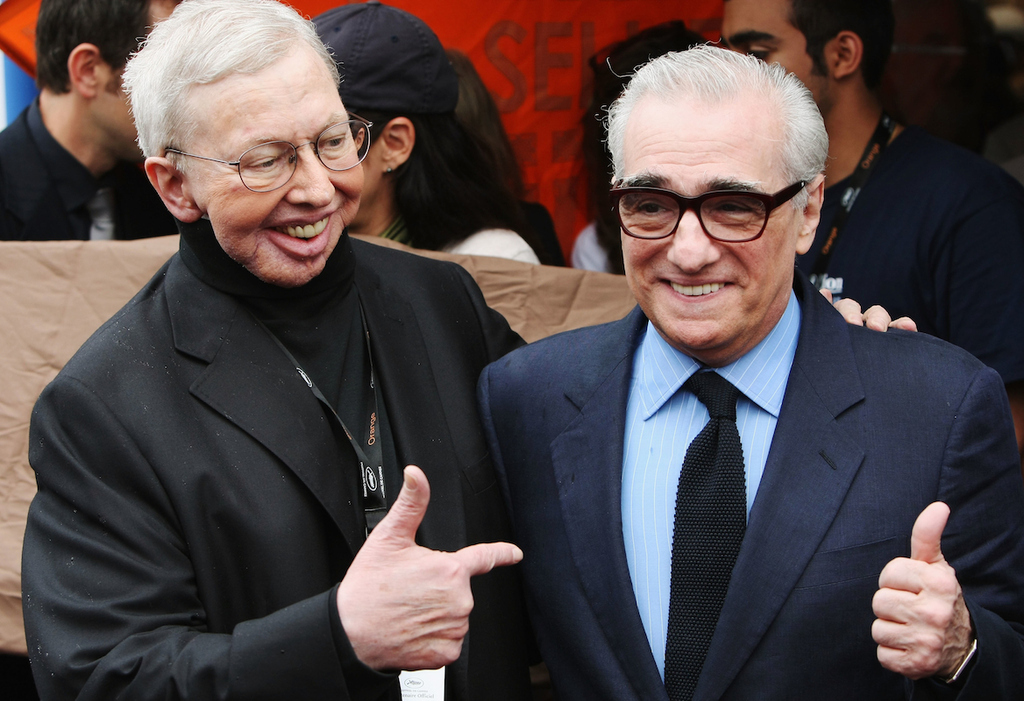

That was silly of me, I know. Since his very first TV appearance with Gene Siskel in 1975 (the same year he was the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize), Roger Ebert had transformed not just into our nation's leading film critic, but also — as New York magazine's film critic David Edelstein put it — into the Mayor of Movie Critic-Ville. His death has accordingly felt a bit like the passing of a head of state, a loss not just of someone for whom we have great affection, but of someone with real authority. And now that he's gone, I'm left to look back at the trajectory of his career — a career that has mirrored the entire profession of film criticism — to work out how anyone could, or would, succeed him.

Throughout the '80s and '90s, Ebert's star was a binary system, his thumb entwined (figuratively) with Gene Siskel's not just on their show, but on countless appearances on Carson, Letterman, Leno, Arsenio, Conan, and Oprah. Those appearances were a chance for both men to have great fun spoofing their own prickly relationship and reinforce their status as the nation's most famous arbiters of cinematic quality. As tickled as we were by their verbal sparring, they spoke with such commanding — yet relatable — eloquence that we also hung on their every word, whether we agreed with them or not. TV film critics like Joel Siegel, Gene Shalit, and Leonard Maltin also became household names, but Siskel & Ebert remained the gold standard. "Two thumbs up," their trademark phrase (literally), may have reduced their conversations to a binary "yea or nay" result. But their power was more than just their facile shorthand for their complex opinions. It wasn't about their individual tastes — Siskel had a soft spot for the gross-out humor of the Farrelly brothers, while Ebert at times championed movies that left some scratching their heads (Dark City, Minority Report, and Crash all topped his Top 10 lists). It was that these two regular-looking guys on national television cared that much about the movies that helped us to care more about them, too.

When Siskel passed away in 1999, also after a battle with cancer, Ebert gracefully carried the mantle of being America's Movie Critic for the rest of his life. But he also presided over the the slow, sad decline of the very thing that elevated him to that status in the first place. After auditioning a series of guest hosts, Ebert settled on his handsome and agreeable Chicago Sun-Times colleague Richard Roeper to join him in Siskel's seat in the balcony. I don't mean to bag on Roeper — he seems like a perfectly decent guy — but he just wasn't in the same league as Ebert, and the show suffered for it. It didn't help matters that the 2000s marked Hollywood's steady transformation into a factory of enormously budgeted franchise pictures geared to such a broad audience that they popularized the lovely term "critic proof." The result: It's just not all that fun (or illuminating) to watch a titan of film criticism debate a well-meaning movie reviewer over just how bad the second Charlie's Angels movie is.

In 2006, Ebert took what turned out to be a permanent leave of absence from the show to battle the cancer that would eventually take his jaw and his speaking voice. At roughly the same time, newspapers began tightening their belts by laying off their local critics, which led the entire critical community to wonder aloud (and often) just how relevant the film critic is anymore to the national conversation. Things were even worse for critics on TV.

Two years after Ebert went off the air, both he and Roeper formally left At the Movies over a contract dispute. The syndication company, Disney-ABC Domestic Television, attempted a disastrous reboot of the show starring the affable Ben Mankiewicz and the excitable Ben Lyons, a.k.a. the man who declared I Am Legend one of the greatest movies ever made. After just about a year's worth of ridicule, Disney mercifully replaced the Bens with The New York Times' A.O. Scott and the Chicago Tribune's Michael Phillips. Thank goodness! cried cinephiles everywhere, genuine critics! But the new duo still didn't have that same nerdy frisson shared by Ebert and Siskel — like so many in their profession, Scott and Phillips were far more engaging on the page than on the screen. Disney outright canceled At the Movies in 2010.

The next year, Ebert himself attempted to revive the franchise, bankrolling out of his own pocket the syndicated public television show Ebert Presents: At the Movies, featuring the Associated Press' Christy Lemire and the Chicago Reader's Ignatiy Vishnevetsky as the main critics. Both lovely, lively TV presences, they nonetheless did not inspire nearly enough juice for Ebert and his wife Chaz to drum up the underwriting funds to support the show, and it was put on indefinite hiatus. As was the very idea of a national TV film critic.

Between his own personal and professional setbacks and the dimming influence of his profession, Ebert could have faded into quiet convalescence. Instead, he made a beeline for the one place where audiences still passionately talked about the movies: the internet. (In truth, Ebert had been an early acolyte of cyberspace: In 1994, I can vividly recall using my high school library computer to look up Ebert's reviews via a dialup modem and an ancient version of Prodigy.) Much has been made already of the irony that the internet transformed Roger Ebert's voice as a writer just as he'd been robbed of it as a speaker. But it's worth noting that this final act of his career stretched well beyond film criticism. He wrote about politics. He wrote about his wife. He wrote about death. He wrote about videogames and Twitter, about Catholicism and his captions of New Yorker cartoons. And he was a voracious presence on Twitter, sending out 31,260 funny, wise, and cranky tweets into the world. Not all of his profuse output was brilliant, but it was always striving to connect with the reader with the specific kind of immediacy only the internet provides.

Just as he had helped to make film criticism accessible for a wide audience by bringing it to TV, Ebert helped to popularize the idea that you can be a deeply engaged critic online. Film critics, at their very best, capture and comment on the experience of the film as it is — good, bad, or indifferent. Ebert managed to transmute that skill into capturing and commenting on the experience of life itself.

Now that he's gone, I'm left to ask the inevitable (and unfair) question: Will we ever see the likes of Roger Ebert again? Will anyone, can anyone, achieve the same combination of his professional stature, unmistakable voice, and enormous reach?

For one, not only are there no more film critics on national television, but national television isn't the place people turn to to talk about movies anymore — or, at least, talk about them critically. We do that on the internet, a global echo chamber of clashing opinions in which a single authoritative voice has to be that much more clear and loud and unique even to be heard. Consider: The chief film critic for The New York Times, A. O. Scott, has fewer followers on Twitter than the gentleman known as FILM CRIT HULK.

For another, film criticism has not been the most exciting area of cultural exchange for a while now, thanks to the well-documented migration of quality adult dramas from movie screens to television sets. When we want to engage thoughtfully about a work of popular art, we more often than not race to read what TV recappers are saying on outlets like Vulture, HitFix, TV Line, Time, or Entertainment Weekly (my previous employer). Interestingly, even as TV more and more takes on the scope and production value of feature films, recapping critics have largely resisted what most film critics have been expected to do for decades: rate the movies with grades or stars or thumbs. I hope they never do.

Still, there are many film and TV critics and commentators working hard to engage with readers and with their subjects in a 21st century context, developing robust presences both online and in social media: Dana Stevens at Slate, Peter Travers at Rolling Stone, James Poniewozik at Time, Emily Nussbaum at The New Yorker, Alan Sepinwall at HitFix, Matt Zoller Seitz at New York magazine, and freelance writer and author Mark Harris (a personal friend and mentor) are just a few of them. My former colleagues Ken Tucker and Lisa Schwarzbaum are also among this group, but they both recently parted ways with Entertainment Weekly earlier this year after Time Inc. announced company-wide layoffs. Their departure and the recent shuttering of the Boston Phoenix speak directly to how challenging it is today to maintain a meaningful position in the critical conversation.

As I noted earlier, it is entirely unfair to compare any of these smart, engaging writers to Roger Ebert — he remains a singular figure. He once said, however, that "clear-minded people should remain two things throughout their lifetimes: Curious and teachable." Instead of one major voice, I can now count myself a part of an entire ecosystem tackling culture both high and low — an ecosystem Ebert spent his life cultivating. No one will be able to recreate Ebert's unique path into so many people's lives. But curious and teachable cultural thinkers are already charting new ones.