For more than 40 years, no single director has more defined what we think of when we think of the movies than Steven Spielberg. To date, his feature films have grossed $4.45 billion in North America and $9.36 billion worldwide, more than any other filmmaker in history by a comfortable margin. His movies have been nominated for 128 Academy Awards and won 32, and Spielberg personally has been nominated for 16 Oscars, winning three (Best Director for Saving Private Ryan, and Best Director and Best Picture for Schindler's List). And if that’s not enough, Spielberg has also presided over at least two of the most transformative changes of the last 50 years in the movie industry: the creation of the summer blockbuster (with Jaws) and the proliferation of computer-generated imagery in visual effects (with Jurassic Park).

To be sure, Spielberg has not done any of this alone. With George Lucas and Harrison Ford, he helped create Indiana Jones. With Tom Hanks, he established an ongoing creative partnership (and lifelong friendship). His longtime producer Kathleen Kennedy — the woman currently shepherding the revival of Star Wars — got her start as Spielberg's secretary. Just about every one of his films have been tightly edited by Michael Kahn and majestically scored by John Williams. And he's collaborated with a small stable of top-flight screenwriters, including David Koepp, Richard Curtis, Eric Roth, Lawrence Kasdan, Steven Zaillian, Tom Stoppard, Tony Kushner, Joel and Ethan Coen, and Melissa Mathison.

When we go to a Spielberg movie, we know we will see a film made with consummate craft and exhilarating visual style — few directors know better how to harness the tools of pure cinema. But I would argue the artistic constant that has informed Spielberg's career and success more than any other has been his seemingly limitless capacity for empathy. "Movies are like a machine that generates empathy," the late Roger Ebert once said. "It lets you understand a bit more about different hopes, aspirations, dreams and fears. It helps us to identify with the people who are sharing this journey with us."

Ebert might as well have been describing Spielberg's entire career, and I know that because, like a crazy person, I screened all 30 of Spielberg's theatrical feature films in chronological order, and then ranked them from worst to best. (I sadly chose not to include his celebrated 1971 TV movie Duel, because Spielberg's other two TV movies — 1972's Something Evil and 1973's Savage — are out of print. I also skipped 1983's Twilight Zone: The Movie, since Spielberg directed just one of five segments in the film.)

By my count, only three of Spielberg's movies are irredeemably bad. The rest range from merely flawed (perhaps deeply so) to among the best films ever made. Here they all are, and the comments are wide open for you to disagree.

30. 1941 (1979)

Starring: Nancy Allen, Dan Aykroyd, Ned Beatty, John Belushi, John Candy, Bobby Di Cicco, Joe Flaherty, Lorraine Gary, Murray Hamilton, Christopher Lee, Tim Matheson, Frank McRae, Toshirô Mifune, Warren Oates, Slim Pickens, Wendy Jo Sperber, Robert Stack, Treat Williams

Written by: Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale (based on a story by Zemeckis, Gale, and John Milius)

It has long been conventional wisdom that 1941 is Spielberg's worst film, which is likely why it has dwindled into an obscure corner of his career, mentioned in passing, if at all. Well, I am here to tell you that watching this movie now is an exercise in absolute shock. 1941 is meant to be a screwball comedy about the panic that grips Los Angeles in the days after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor plunged America into World War II, but I laughed out loud exactly one time, at a throwaway gag about a ventriloquist dummy. The rest of the time, my mouth hung agape at the parade of inchoate insanity — and misogyny! and racism! — that tumbled onto the screen over an interminable two hours.

One example: Roughly 13 minutes into the film, horndog Capt. Birkhead (Matheson), and general's secretary Donna Stratton (Allen) have this alarming exchange:

Birkhead: "Donna Stratton, after all this time. How long has it been?"

Stratton: "Not long enough."

Birkhead: "Well, you're not still sore are you, Donna?"

Stratton: "Yes, in a number of places."

Birkhead: "Ha ha ha! Same old Donna!"

And it gets so much worse! A USO emcee (Flaherty) says this into his radio mic after the dance hall has been demolished in a brawl by enlisted soldiers: "I hope you enjoyed tonight's program. I'd like to thank all the GIs for helping to make tonight's evening such a memorable occasion. Maybe in the future we can have Negroes come in and we'll stage a race riot right here." (By the way, that really happened.) There's the moment Col. "Madman" Maddox (Oates) says of Birkhead, whom he mistakes for a spy, "He's a little tall for a Jap. … Check him for stilts." There's the scene in which Candy is covered in black soot, and McRae (the only black actor of any significance in the film) is covered in white flour, and McRae says to Candy, "Hey, get to the back of the tank!" And then there's the sociopathic corporal (Williams) who maniacally chases after a woman who wants nothing to do with him in a running gag played for laughs up to when he actually begins to rape her — at which point I can only assume the laughter was meant to stop until she is saved by that aforementioned tank.

To be fair, some of these are sins of screenwriting and relics of a coarser era. But Spielberg stages all of it with the subtlety of a thumb in the eye, confusing indiscriminate destruction and flop-sweaty mugging for what makes people laugh. What is doubly surreal is that Spielberg brought such a deft and delightful comic touch to his previous three films, and has continued to for so many of his subsequent movies. Spielberg has said he is not embarrassed by 1941, which, OK, maybe he hasn't watched it in a while, like the rest of humanity. But he also never attempted to direct an outright comedy again. Can you blame him?

29. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984)

Starring: Harrison Ford, Kate Capshaw, Ke Huy Quan, Amrish Puri

Written by: Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz (from a story by George Lucas)

From the initial shot of the second Indiana Jones movie, you can feel, for the first time in Spielberg's career, the pressure to surpass his past success. It starts with an opening credits rendition of "Anything Goes" performed by nightclub singer Willie Scott (Capshaw), in Mandarin, in a Shanghai establishment called "Club Obi Wan." At one point, Willie and the camera disappear inside a giant, smoking dragon's head, and the movie is overtaken by a fantastical high-stepping tap dance number out of a 1930s musical that makes zero sense in an Indiana Jones movie. From there, the movie shifts into a James Bondian standoff between a Chinese mobster and Indy in a white tux jacket; then into a madcap comedy with Indy scrambling for a poison antidote; and then into a credulity-straining adventure sequence in which Indy, Willie, and Indy's kid sidekick Short Round (Quan) "parachute" out of a crashing plane in an inflatable raft, onto a Himalayan mountainside, and into a raging rapid. "Anything Goes," indeed!

Once Indy, Willie, and Short Round wash up near a small, decimated village in India, the movie finally calms down. But the wonder and joy baked into every second of Raiders of the Lost Ark is replaced in Temple of Doom with a manic, lurid meanness, as an unexpected genre takes root: horror. At his best, Spielberg can stage violence that knocks the wind out of you, but the violence in Temple of Doom is just brazen and grim — shocking, sure, but hollow. The sequence involving Thuggee cult leader Mola Ram (Puri) pulling the still-beating heart out of a screaming human sacrifice famously led to the creation of the PG-13 rating — and yet, ironically, that scene is so grisly that the movie might not have managed to earn that rating today.

And I don't even know what to say about what Capshaw goes through in this movie. Temple of Doom marks the beginning of one of the most successful relationships in Hollywood (Capshaw and Spielberg married in 1991), but Spielberg really put her through it here, both physically — that dark room seething with bugs! — and, I would imagine, emotionally. Although Capshaw works overtime to make Willie a likable sexual foil for Indy, she remains a gold-digging, hyperfeminine caricature who is unfortunately timed to the break-ups Spielberg and Lucas were going through while making this film.

And yet, despite all of this, Ford still manages to maintain Indy's integrity, his good humor, and his sense of heroism. That is no small thing, and speaks to how, and how much, the character has endured for nearly 35 years.

28. The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997)

Starring: Jeff Goldblum, Julianne Moore, Pete Postlethwaite, Vince Vaughn, Richard Schiff, Vanessa Lee Chester, Arliss Howard, Peter Stormare, Richard Attenborough

Written by: David Koepp (based on the novel by Michael Crichton)

In 1993, Jurassic Park heralded nothing less than a new era of visual possibility in filmmaking, thanks to the movie's careful, pointed use of cutting-edge computer-generated visual effects.

In 1997, The Lost World: Jurassic Park became an essential example of how overusing computer-generated visual effects can make your movie look like crap.

It's crazy how markedly different these two movies look today, given the vast glut of CGI that flooded the movies in the wake of Jurassic Park's success. But again and again, The Lost World grinds to a halt to gawk at the profusion of dinosaurs inside it. Look, a rampaging triceratops! And two T. rexes! And a whole pack of raptors! And since these sequences have almost nothing to do with whatever amounts to a plot in The Lost World, all we can do is ponder how muddy and indistinct its dinosaurs look, especially in comparison to the vivid creatures in Jurassic Park.

This would be tolerable if Spielberg's filmmaking didn't feel so perfunctory. The Lost World is his first film after Schindler's List, made after the launch of DreamWorks SKG held his attention for four years, the longest he's ever gone without directing. You can feel him straining for a reason for this movie even to exist beyond watching dinosaurs chomp on some impressively stupid humans. The only time The Lost World and Spielberg ever really spring to life is when a T. rex starts rampaging through San Diego, and the movie becomes, in essence, a parody of itself. Maybe Spielberg should just stop making sequels?

27. Hook (1991)

Starring: Robin Williams, Dustin Hoffman, Julia Roberts, Bob Hoskins, Maggie Smith, Caroline Goodall, Charlie Korsmo, Amber Scott, Dante Basco

Written by: Jim V. Hart and Malia Scotch Marmo (Based on a story by Hart and Nick Castle, and the play by J.M. Barrie)

Although Spielberg has been tagged as a director obsessed with making movies from a child's point of view, especially in the first half of his career, this is the only one of his films that could be called a "kids movie." Its central conceit — that Peter Pan grew up, started a family with Wendy Darling's granddaughter, and transformed into a work-obsessed killjoy named Peter Banning (Williams) — may apply to the parents in the audience, but everything else about this movie is aimed squarely at their children. The story is basic: Peter's two kids are kidnapped by Capt. Hook (Hoffman), and Peter has to learn how to become Peter Pan again to save them. The acting is broad — Hoffman especially chews the scenery like it's a full-course meal. And the aesthetic is aggressively fake, especially the Neverland sets, which look like the best dioramas ever on a Disney World ride.

Which is fine! I remember devouring this movie as a kid, and thinking Peter's successor Rufio (Basco), a skateboarding punk with three red mohawks, was the coolest person I'd ever seen. As an adult, I can appreciate the uncomplicated diversity of the Lost Boys, and even the film's unapologetically mushy lessons about treasuring your children and honoring your parents. One thing that is not easy on kids or adults? The bloated 140-minute runtime. And Spielberg's penchant for indulging in easy sentimentality is at its apex here: all those glowing shots of the Lost Boys staring at Peter with beatific wonder; all those times Peter's daughter scolds Hook for needing a mommy; all those shots of Roberts, as Tinkerbell, doing nothing but smiling her Julia Roberts smile. I caught myself rolling my eyes more than once, but that is nothing compared to the unfortunate shock of the film's final moment, in which Williams says, "To live… to live would be an awfully big adventure." To be reminded of the circumstances of Williams' death at the end of a movie so steeped in kid-friendly, soft-focus warm fuzzies is not the film's fault, of course. But, still, I screamed.

26. Always (1989)

Starring: Richard Dreyfuss, Holly Hunter, John Goodman, Brad Johnson, Audrey Hepburn

Written by: Jerry Belson (based on the film written by Dalton Trumbo)

This is such a peculiar movie for Spielberg and, really, for anyone. It’s a remake of a 1943 WWII romance that's been updated from the world of fighter pilots to the modern day world of firefighter pilots who still have 1943 movie names: Dreyfuss plays the risk-taking ace Pete Sandich, Hunter is his headstrong girlfriend Dorinda Durston, and Goodman is their twinkly buddy Al Yackey. Spielberg presents their lives in such a fishbowl of gauzy sentiment that it's as if the characters are the only people left on Earth, forced to look at each other with dewy-eyed affection when they aren't stamping out incredibly dangerous fires in unpopulated mountain forests.

Because they’re shot by Spielberg, those aerial firefighting scenes still have a thrilling kick, especially when one of those fires — and this isn't a spoiler; it’s the premise of the film — kills Pete. He becomes a guardian angel with a mentor named Hap (Hepburn, luminous in a "special appearance" that was also her final onscreen performance). And in keeping with the film's overall weirdness, Pete takes the devastating news that he's dead in total stride. That is, until he learns that his new charge Ted Baker (Johnson), a handsome wannabe pilot, happens to be sweet on Dorinda, leading to a series of obvious scenes in which Pete tries to sabotage their relationship, until he accepts that, you know, he's dead. As a meditation on grief, it's kind of silly. And while it is refreshing that the movie’s gorgeous, empty-headed love interest is a man — Ted is a perfect specimen of late '80s GQ beefcake — that does not make him interesting! At one point, actually, Dorinda says of Ted, "I can't be with a guy who looks like I won him in a raffle,” which Hunter sells perfectly. Hunter does everything she can, really, to sell the entire sappy story, and in the face of that absurd name, Dorinda becomes one of Spielberg's most self-possessed and fully-realized female characters. That probably says something about the state of women in Spielberg's films, which brings me to…

25. The Terminal (2004)

Starring: Tom Hanks, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Stanley Tucci, Zoe Saldana, Diego Luna, Chi McBride, Kumar Pallana, Barry Shabanka Henley

Written by: Sacha Gervasi and Jeff Nathanson (based on a story by Gervasi and Andrew Niccol)

In the mid-2000s, Spielberg embarked on what probably exists only in my head as his post–9/11 trilogy with three movies of increasing seriousness and intensity. The first: this light-as-a-down-feather-pillow fable about Viktor Navorski (Hanks), a decent, bumbling Tom Hanksian fellow from the fictional Eastern European nation of Krakozhia who gets trapped in the international terminal at New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport after his country collapses into civil war. Because he's Spielberg, an entire airport terminal set was built for the film, and he uses every inch of it to romanticize the soothing purgatory of air travel and rescue it from the high anxiety of the previous three years. The film is most effective, though, whenever Viktor butts heads with Frank Dixon (Tucci), a hidebound Homeland Security official who can see Viktor only as an irritant to be passed off onto someone else. Tucci pulls off the tricky feat of evoking Bush-era cocksure indifference to anyone with a funny name or accent without making Frank into a mustache-twirling villain.

But instead of a tight 90-minute movie about Viktor’s struggles with Frank, Viktor also spends a great deal of time wooing a flight attendant named Amelia Warren (Zeta-Jones). This is the kind of female character who's introduced to the audience by breaking a heel; who complains about her lousy married boyfriend and then says, "I just wish the sex weren't so amazing"; who thinks announcing that she’s 39 represents a shocking personal disclosure. Zeta-Jones looks marooned trying to make sense of Amelia, and only Hanks's innate charm and comic poise keeps the movie from falling apart whenever she's onscreen. There are directors who are great at bringing deeply flawed female characters to life. Spielberg has struggled to be one of them.

24. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)

Starring: Harrison Ford, Cate Blanchett, Shia LaBeouf, Karen Allen, Ray Winstone, John Hurt, Jim Broadbent

Written by: David Koepp (based on a story by George Lucas and Jeff Nathanson)

The fourth Indiana Jones movie isn't the disaster people remember it to be, but I think it's earned that reputation because it is, unmistakably, a disappointment. The "nuke the fridge" sequence is notorious, of course, but I'd argue that forcing LaBeouf, as '50s greaser Mutt Williams (aka Indy Jr.), to swing with a pack of monkeys in the jungle is one of the most embarrassing things Spielberg's ever filmed. The movie is so glutted with CGI, in fact, that long stretches of it look like a second-rate video game. And while I can understand why Lucas insisted on evoking the dime store sci-fi of the 1950s — giving a Hollywood spit-and-polish to the pulp adventure tales of Lucas and Spielberg's childhoods is why Indiana Jones exists — the movie cannot escape the fatal flaw that Indy could scarcely care less about little green men.

That's the thing: In the Indiana Jones movies that really work, Indy has a personal investment in the plot, whether he's partnering with his old flame Marion (Allen) to defeat an old enemy in Raiders, or with his father to fulfill his dad's greatest obsession in The Last Crusade. In Crystal Skull, Indy's reunion with Marion, and his discovery that Mutt’s his son, never really link up with the main plot. So no matter how many breakneck action set-pieces Spielberg concocts, they don't amount to much more than digital sound and fury, signifying nothing.

And yet! There is an undeniable satisfaction in seeing Ford back in Indy's fedora, swinging on his whip with commies on his tail, and the fact that we first see him doing it in the colossal government warehouse from the final shot of Raiders is the best kind of fan service. And speaking of Raiders, remember that one line of Indy's from it, "It's not the years … it's the mileage"? Well, whenever Spielberg zeroes in on the two decades’ worth of mileage Ford brings to Indy in Crystal Skull, I am reminded all over again why Indiana Jones remains one of the great movie characters of all time. Spielberg has made no secret of his desire to make a fifth Indiana Jones movie with Ford, and if Lucas's cockamamie ideas have followed him into retirement, I can only hope that we'll finally get the movie we, and Indy, deserve.

23. The Adventures of Tintin (2011)

Starring: Jamie Bell, Andy Serkis, Daniel Craig, Nick Frost, Simon Pegg

Written by: Steven Moffat, Edgar Wright, and Joe Cornish (based on the comic book series by Hergé)

I know nothing of the beloved Hergé comics that inspired Spielberg to collaborate with producer Peter Jackson on his first motion-capture movie, but I took to their playful, color-drenched interpretation of that world instantly. Every shot in The Adventures of Tintin is just gorgeous, and with total freedom to place his virtual camera wherever he wants — kind of like, yes, a video game — Spielberg keeps the screen constantly alive with movement and action. It is, in many ways, the purest expression of his visual ambitions and abilities as a filmmaker.

As a storytelling engine, however, the title character of Tintin, as performed by Bell, is not much more than a cypher. Tintin keeps chasing after the secret tucked inside a model ship he purchased on a whim just because, well, he thinks it's a good story, but we never get to understand him beyond that. Fans of the comics may know better, but as far as this movie is concerned, he's all gumshoe enthusiasm, and no soul. The mystery is extremely personal, at least, for Tintin's compatriot, Captain Haddock (Serkis), a drunkard chasing after a family legacy he's largely forgotten in a haze of whiskey. But when it’s finally revealed, it doesn't really add up to much more than a standard treasure hunt. Actually, I would compare Tintin to the transitory pleasures of a video game, but I've played several games that are more fun, and less forgettable.

22. Empire of the Sun (1987)

Starring: Christian Bale, John Malkovich, Miranda Richardson, Nigel Havers, Joe Pantoliano

Written by: Tom Stoppard (based on the novel by J.G. Ballard)

From a pure filmmaking standpoint, Empire of the Sun was perhaps Spielberg's most complex production — emotionally and logistically — up to this point in his career. As we trace the story of Jamie Graham (Bale, so young!), a British boy separated from his parents during the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in WWII, there are several massive feats of filmmaking here that seem like miracles to a modern eye. Spielberg actually shot in Shanghai, using extras reportedly numbering in the thousands, and the scope he achieves in these sequences is just astonishing. They literally do not make movies like this anymore. In fact, filmmaking legend David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia, The Bridge on the River Kwai) was initially supposed to direct this film, and as Jamie falls in with an opportunistic American (Malkovich, so creepy!) and then into a prison camp, you can feel Spielberg drawing inspiration from Lean's talent for conducting scenes on an enormous scale.

The emotional chords in the film, however, prove trickier to master. As a coping mechanism, Jamie treats the war and his own survival like a fantasy he can't quite snap out of, and while in some ways, it's gutsy of Spielberg to approach the film with that same childlike dissociation, it puts the characters' emotional lives just out of our reach. There is a chill to this movie that evokes Stanley Kubrick for me even more than Lean, a sense we are observing things at an intellectual remove. When Jamie's life falls apart in the third act into an overwrought fever dream, whatever purchase I had on his character slipped away into abstraction. It's the first time Spielberg can't quite find a cohesive ending, a nagging creative tic that would haunt him for the rest of his career.

21. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Starring: Haley Joel Osment, Jude Law, Frances O'Connor, William Hurt, Sam Robards, Jake Thomas

Written by: Steven Spielberg (from a screen story by Ian Watson, and short story by Brian Aldiss)

Speaking of Stanley Kubrick: For nearly two decades, the exacting filmmaker turned to Spielberg as a sounding board, confidant, and producer for a grand sci-fi fairy tale he wanted to make about a robot boy named David who is programmed to love. After Kubrick died suddenly in 1999, Spielberg finished the screenplay and directed the movie himself. And that is how one of the most curious artifacts in recent cinema history was born.

It would be easy to attribute A.I.'s scenes of cozy domesticity — like David (Osment) learning how to live with his new parents Monica (O'Connor) and Henry (Robards) — to Spielberg, and its scenes of psychological brutality — like Monica abandoning David in the woods while she feebly sobs, "I'm sorry I didn't tell you about the world" — to Kubrick. But David's love for his mother is so absolute that it comes off as a disquieting obsession, and Monica's abandonment of David is certainly no less brutal than so many scenes Spielberg staged in Schindler's List or Saving Private Ryan, or Jaws, for that matter. For long stretches of A.I., the creative partnership between these two filmmakers sits in an effective-if-uneasy balance — they both chase their shared obsession with the moral limits of technology into some frightening and fascinating places. And it is all buoyed by Osment's astonishing performance as David, executed with a level of emotional precision that most adult actors can’t even achieve.

As A.I. progresses, however, the seams do start to show — quite literally. Sequences abruptly end and shift in tone, and characters seem to appear out of nowhere and then disappear just as suddenly. And then there's the film's epilogue, set 2,000 years in the future when the Earth is populated by a race of super-advanced robots and David has become the Jesus-like oracle to their ancient human creators. This wild narrative jump is unmistakably Kubrickian, but rather than keep it spare and mysterious, Spielberg overexplains everything to the point of frustration and tedium. A.I. leaves me with many troubling questions — about parenting, about childhood, about my relationship with technology, and about technology's relationship with me. But the one that I ponder the most is what this movie would have looked like had Kubrick lived to direct it himself.

20. Bridge of Spies (2015)

Starring: Tom Hanks, Mark Rylance, Amy Ryan, Scott Shepherd, Austin Stowell, Alan Alda, Jesse Plemons, Sebastian Koch, Will Rogers

Written by: Matt Charman, and Joel and Ethan Coen

One of the more interesting recurring themes in Spielberg's career is his ambivalent-at-best, cynical-at-worst attitude toward government power. Even when his films are explicitly about the triumph of American authority (like Saving Private Ryan and Lincoln), Spielberg repeatedly places faceless government jackasses in the way of, or in direct opposition to, his protagonists' goals and aspirations. And yet there is scarcely a filmmaker alive who has done more to mythologize the idea of America in his career.

That tension is on grand display in Bridge of Spies, which is based on the true story of private insurance lawyer James B. Donovan (Hanks), who was first tasked with the doomed legal defense of alleged Soviet spy Rudolf Abel (Rylance) in 1957, and then helped to successfully negotiate the release of two imprisoned Americans in exchange for Abel in the early 1960s. In the film, Donovan has to keep pushing back against authority figures flouting constitutional ideals in favor of selfish expediency, including the CIA minders who are only interested in winning back Francis Gary Powers (Stowell), a spy plane pilot shot down over Russia, and not Frederic Pryor (Rogers), an innocent college student arrested in East Berlin as the Berlin Wall is under construction.

When we see how Powers and Pryor are captured, Spielberg’s directorial powers are at a full boil — the spy plane crash especially is as gripping as you would expect from him. But otherwise, we spend almost no time getting to know Powers and Pryor, and as Abel, I found Rylance to be inscrutable (though his understatement was engrossing enough to win him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, only the second acting Oscar ever for a Spielberg film). Instead, the filmmaker fixates on the paranoia of the Cold War, from the duck-and-cover films shown in American elementary schools to the bombed-out desperation of East Berlin, with the same cinematic understatement he employed in Lincoln. And in the center of all this dour gloom, Hanks’s Donovan is a steadfast pillar of American decency and determination, the exceptional regular guy who reminds us of our best selves. It is admirable, even stirring, but it also adds up to a surprisingly muted movie.

19. Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

Starring: Richard Dreyfuss, Melinda Dillon, François Truffaut, Teri Garr, Bob Balaban

Written by: Steven Spielberg

There are actually three separate versions of Spielberg's third feature: the version that first played in theaters, which Columbia Pictures rushed into release; the re-edited "Special Edition" released in 1980, for which Spielberg restored deleted scenes and shot additional footage and visual effects; and the 2001 "Collector's Edition," which is a kind of hybrid of both previous versions. The "Collector's Edition" is the one I rewatched for this ranking, largely because that is the version that is easiest for most people today to find. (The only other time Spielberg did this to himself is with the updated visual effects in the 20th-anniversary re-release of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, a mistake that he has since all but repudiated.)

No matter which version of Close Encounters you are watching, however, the movie is a peculiar mishmash of an epic conspiracy thriller, harrowing domestic drama, and blissed-out sci-fi adventure. The script, credited to Spielberg, makes a fetish of avoiding standard dialogue, and works overtime to keep the full story at arm’s length from the audience until the very end. In a career spent defining the modern sense of mainstream filmmaking, Close Encounters is, in essence, Spielberg's closest attempt at an art film.

And some of it really works even when it shouldn't. I love watching filmmaking iconoclast Truffaut play the elfin, wonderstruck center of what is otherwise a massive display of autocratic government power. (Every time I see this movie, I keep waiting for an anonymous military official to turn to another anonymous military official and ask, "Where did this French guy come from again?") And the early scenes of light-drenched UFO encounters match their sense of awe with a dread and panic that feel absolutely right.

I'm less keen on the long sections of the film in which Dreyfuss, as blue-collar husband and father Roy Neary, spirals into a total nervous breakdown after his close encounter, and terrorizes his family in the process. Spielberg has spent his career exploring divorce, but this is pretty much the only time he's depicted what it can actually look like when a marriage disintegrates. The movie, however, stacks the deck — Garr, as Roy's wife, Ronnie, is wasted playing a thankless nag, and our knowledge that Roy isn't actually crazy throws these emotionally raw scenes off balance. The famous final act, meanwhile, pulls us back into a full-blown science fiction extravaganza in which the aliens make first contact in a coruscating display of light and music. But — whispers — I think those scenes are kind of boring. I respect the hell out of this movie, and Spielberg's ambition for it. But I'm not sure it completely hangs together.

18. The Sugarland Express (1974)

Starring: Goldie Hawn, Ben Johnson, William Atherton, Michael Sacks

Written by: Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins (based on a story by Spielberg, Barwood, and Robbins)

It is scarcely a surprise that even some serious Spielberg fans may not have heard of his first feature film. Unlike the rest of the movies from his early career, The Sugarland Express is not a classic genre picture, and it isn't really designed to be popular entertainment. It isn't told from a child's point of view, it doesn’t feature any grand acts of heroism, and its ending is far from happy.

And yet, watching it today, The Sugarland Express is also unmistakably a Steven Spielberg movie. Inspired by a true story, the film follows young mother Lou Jean (Hawn), who sneaks her husband Clovis (Atherton) out of jail so he can help her win back her son from the care of God-fearing foster parents living in Sugar Land, Texas. Their plans go sideways after, out of desperation, they kidnap a Texas Public Safety Patrolman Officer Slide (Sacks) and commandeer his car, which slowly transforms into a minor media event after a parade of police cars and well-wishers begin tailing the trio as they slowly drive through the Texas countryside.

Spielberg marshals the comic spectacle of hundreds of cars lumbering down the long highways and through tiny Texas towns like it's his tenth feature and not his first. His distinctive visual command is uncanny here, with so much care and attention paid to how objects move fluidly across the frame and through it — and not just as a pleasant diversion, either. Spielberg painstakingly grows the movie's scope to build our sense of Lou Jean and Clovis's escalating celebrity, and our inevitable dread over what awaits the couple as they close in on their goal. In one scene, a pair of self-appointed citizen police officers shoot up a car dealership as Lou Jean, Clovis, and Slade run for their lives, and what could have played as farce instead feels genuinely terrifying. (This film’s wariness of gun violence stands as a fascinating counterpoint to all the blithe gunplay in the Indiana Jones movies.)

Like so many rookie directors, however, Spielberg spends so much time showing what he can do with the camera that he neglects to invest time in the young and hopeful Lou Jean, Clovis, and Slade. He treats them more like curiosities than characters, and by the time that camera finally does begin to investigate their faces, it's almost too little, too late. Spielberg has so often fixated on happy endings that the rigor of his first feature's downbeat final act is that much more impressive. But as things begin to fall apart for Lou Jean and Clovis, I was not, in the end, all that moved.

17. The BFG (2016)

Starring: Mark Rylance, Ruby Barnhill, Penelope Wilton, Jemaine Clement, Rebecca Hall, Rafe Spall, Bill Hader

Written by: Melissa Mathison (based on the novel by Roald Dahl)

We think of Spielberg as a director who knows to his bones how to capture the world from the eyes of a child, but since 2001's A.I. Artificial Intelligence, he has spent his career preoccupied with the harsher concerns of adulthood. Even Dakota Fanning's terror in War of the Worlds is ultimately seen through the prism of her father's impotent dread at barely being able to protect her, and the titular boy hero of The Adventures of Tintin is so preternaturally capable and confident, he might as well be 35.

So The BFG — a gentle fable about a young girl and her big, friendly giant — already stands out as a marked, almost jarring shift in tone and subject matter for the filmmaker. Our hero, Sophie (Barnhill, plucky and unfussy), is an orphan living in a vaguely storybook version of 1980s London. After seeing a gargantuan cloaked figure (Rylance, digitally embiggened via performance capture) from her dormitory window in the dead of night, she’s snatched up and whisked away to Giant Country. There, Sophie takes in her predicament with remarkable aplomb, and eventually helps the BFG get the better of his even larger, decidedly unfriendly giant brethren by enlisting the support of the Queen of England (Wilton, having a ball).

The movie's plot is slight, even with the thoughtful additions to Dahl's slender novel made by the late Mathison, like giving the BFG a mournful past with a young human boy who we gather was eaten by those awful giants. And the film's initial lumbering pace is at odds with Spielberg's usual crisp command of how to shape a scene. Once the film settles into a serene meditation on how the BFG captures and creates our dreams, however, it becomes clear that Spielberg crafted his film — with its languorous storytelling and fantastical, surreal imagery — to unfold as one giant dream. When taken on that level, it's hard not to be enchanted, but the film would still waft away were it not for Rylance's wonderfully expressive and soulful performance. The BFG may be ancient, but Rylance gives him a youthful spark of unaffected wonder, suggesting that as Spielberg nears 70, he's not nearly done nurturing his inner child.

16. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)

Starring: Harrison Ford, Sean Connery, Alison Doody, Denholm Elliott, John Rhys-Davies, Julian Glover, River Phoenix

Written by: Jeffrey Boam (based on a story by George Lucas and Menno Meyjes)

The only other genuinely good Indiana Jones movie is, perhaps not coincidentally, also the one that is most like Raiders of the Lost Ark. Like the original film, we start with a grand adventure, cut back to Indy's staid life as a professor, and then send him on a quest for a fabled and powerful Judeo-Christian artifact that runs him afoul of the Nazis — this time including, in a gutsy cameo, Adolf Hitler himself.

With The Last Crusade, however, Spielberg and Lucas seem less interested in building up Indiana Jones as a cinema icon than playfully pulling him apart to explore what made the man in the first place. We get an origin story in miniature, with the late Phoenix as a young Indy effortlessly picking up that iconic whip and fedora in a marvelous opening sequence. And we get Sean Connery having the time of his life as Indy's daffy bookish father, transforming the The Last Crusade into one of the funniest films Spielberg's ever made. I barely even care that the plot is sloppy — why are the Nazis desperate to find Indy's dad if he's being kept prisoner in a Nazi castle? — and that Doody makes for a feeble femme fatale. It's all too much fun!

15. Amistad (1997)

Starring: Djimon Hounsou, Matthew McConaughey, Morgan Freeman, Anthony Hopkins, Nigel Hawthorne, David Paymer, Pete Postlethwaite, Stellan Skarsgård, Chiwetel Ejiofor

Written by: David Franzoni

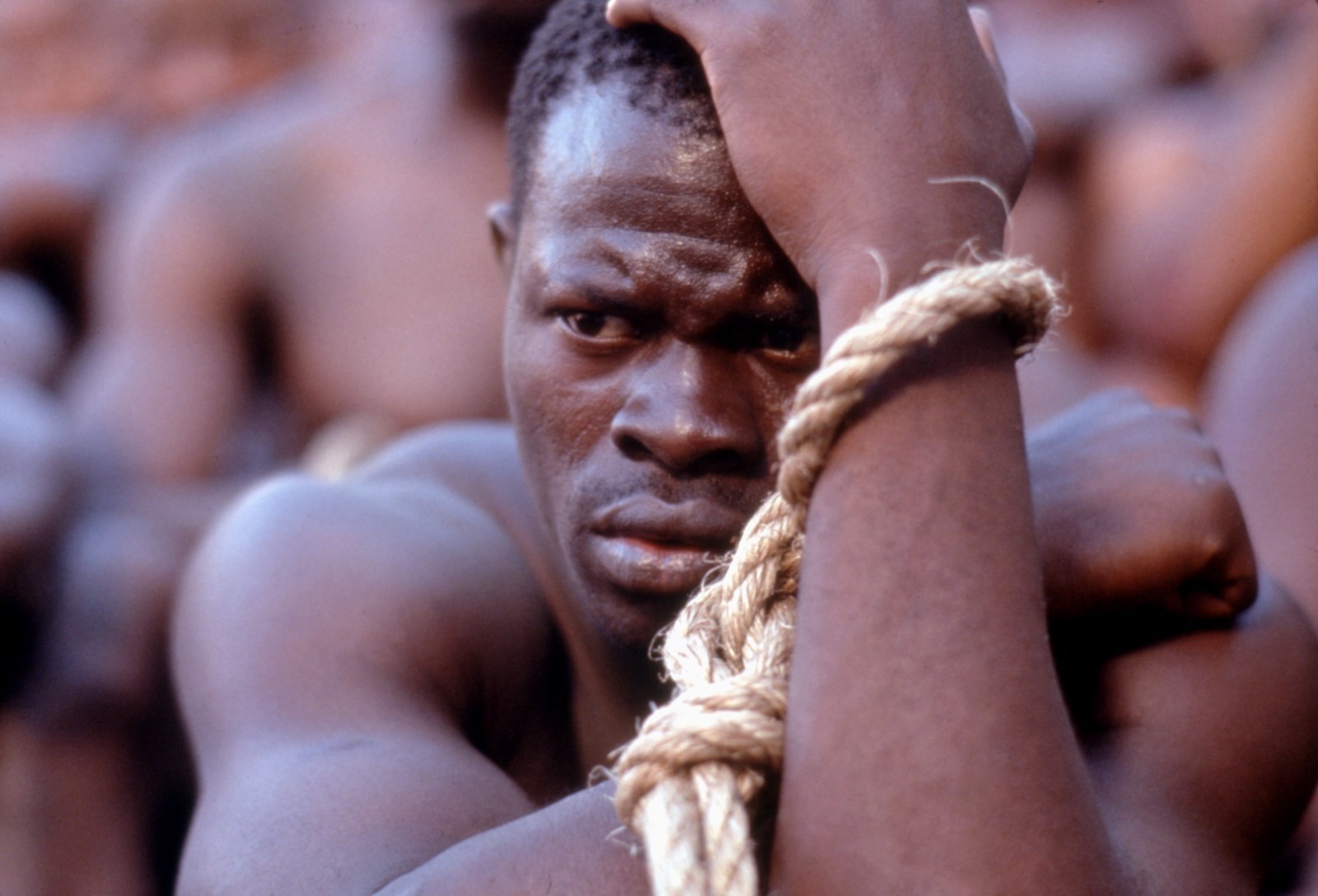

About halfway into Amistad, Spielberg unspools a sequence that flattened me more than anything he's ever done. In 1839, after successfully leading a revolt on the slave ship La Amistad, Cinque (Hounsou) and roughly 40 other West Africans illegally taken from their home find themselves in a middle of a trial for their lives in the United States. After struggling to communicate with their lawyer Roger Sherman Baldwin (McConaughey), Baldwin and his abolitionist patrons (Freeman and Skarsgård) find a sailor (Ejiofor) who speaks Mende, Cinque's language. And when they all sit down for their first real conversation, and Cinque is finally able to explain what happened to him, Spielberg depicts the Middle Passage — the journey made by millions of kidnapped Africans across the Atlantic on slave ships — for really the first time in a major motion picture.

I'm going to presume that anyone who has seen this film cannot forget this sequence, because I never have, and I never will. We see hundreds of men and women stripped naked, shackled, and packed screaming inside the ship's hold. We see them being forced onto the deck to witness a man get whipped into unconsciousness, the blood splattering on Cinque’s face. We see a mother clutch her newborn baby to her chest and quietly fall overboard. And we see a string of captives get chained to a stone anchor and pulled, screaming, into the ocean. Matched with Cinque's ferocious and desperate uprising that opens the movie, this is fearless, indelible, essential filmmaking.

The rest of the movie, alas, is not. Amistad is mostly a studious legal drama, spent largely in courtrooms and climaxing with Hopkins (as former president John Quincy Adams) delivering an 11-minute (!) summation to the Supreme Court as Cinque watches in silence. Hounsou — speaking almost entirely in Mende — is a vital presence throughout, his anger, despair, and intelligence shining through even in the scene in which Baldwin complains to Cinque about how hard his life has become after taking the case. The debates over impending civil war and the morality of slavery in Amistad, however, are not treated as the beating lifeblood of America, but as a soporific exercise in well-meaning grandiloquence. When Spielberg addressed those same two issues 15 years later, he did not make the same mistake again.

14. Jurassic Park (1993)

Starring: Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum, Richard Attenborough, Joseph Mazzello, Ariana Richards, Wayne Knight, Samuel L. Jackson, Martin Ferrero, Bob Peck, BD Wong

Written by: Michael Crichton and David Koepp (based on the novel by Crichton)

As a piece of commercial filmmaking, there is cumulative feeling to Jurassic Park. So much of Spielberg's best expertise in assembling audience-pleasing adventure movies — how to build suspense and pay it off, how to weave in exposition without weighing down the pace, how to shoot visual effects as spectacle but not let them overwhelm the story — is brought to bear here. The T. rex attack and velociraptor hunting sequences still hold up as some of the most satisfying action set pieces Spielberg has ever filmed. They move the story forward, they still make my palms sweat, and they serve as a potent visual metaphor for unchecked technology biting us in the ass. Whenever I see a movie with squishy, chaotic action sequences — like, I don't know, the Spielberg-produced Transformers movies — I often think back to Jurassic Park, and to how much care Spielberg takes in making sure we always know what’s going on, and how much more effective the movie is because of it.

But Jurassic Park is such a tightly built windup toy that it barely leaves room for its characters to breathe. Goldblum, as the rapscallion Dr. Ian Malcolm, and Dern, as the tenacious Dr. Ellie Sattler, make the most of the little they're given here, but even they are playing cartoony archetypes rather than full characters. It's a blueprint this film series has lucratively stuck with up to Jurassic World, which Spielberg executive produced. But in spite of the 13-year-old nerd(ier) version of me who treated this movie like a religious experience, I know Spielberg's uncommon gift for imbuing deep feeling into his most entertaining movies has been put to much better use.

13. War of the Worlds (2005)

Starring: Tom Cruise, Dakota Fanning, Justin Chatwin, Tim Robbins, Miranda Otto

Written by: Josh Friedman and David Koepp (based on the novel by H.G. Wells)

The second film in Spielberg's (unofficial) 9/11 trilogy is the one that most explicitly evokes the collapse of the Twin Towers and the paralyzing panic of that day. It is also a gigantic alien invasion spectacular, the kind of movie Spielberg fans had been hoping he would make for just about three decades. And it is also a movie that more or less climaxes with Tom Cruise disappearing inside what can only be described as a giant alien anus.

The fact that all three of these things can be said about the same movie speaks to the miraculous nature of Spielberg's filmmaking — and his evolution as a director. The sentimentality of his '80s adventure films and the effects-driven awe of his '90s blockbusters have both been stripped away in favor of harsher, more emotionally fraught storytelling. The film's protagonist, a divorced dockworker named Ray Ferrier (Cruise), is a lousy father with a tenuous relationship with his young daughter, Rachel (Fanning), and barely any at all with his teenage son, Robbie (Chatwin). The invasion doesn't so much bring them together as further expose Ray's failings, forcing him to confront just how impotent he is to keep his family safe from a terrifying, unseen enemy. It's a sly, subtle way to explore the impotence most Americans felt after Sept. 11; less subtle, but no less effective, is when Ray comes home after the first attack to discover he's covered in the ashen remains of the people around him.

And watching War of the Worlds far from Cruise’s couch-jumping antics that clouded its release, I have to say, Spielberg knows how to get the best out of him as an actor and as a movie star. Ray is the polar opposite of Ethan Hunt, a man who has no plan and even less trust in his own instincts, and Cruise plays him with an unsparing, ragged honesty that I've never really seen from him before. If I only could say the same of Robbins! As a mania-seized EMT who shelters Ray and Rachel in his basement, he overacts like he's in an alien invasion movie directed by Roland Emmerich. His scenes stop the movie cold, and it never quite recovers, especially since Spielberg decides to keep the uncinematic ending from Wells' seminal novel — that germs kill the aliens off-camera. Ray does at least get to play the hero once, when he gets sucked into an alien tripod in a desperate (and successful) attempt to save Rachel from it. And that scene is just the gift that keeps on giving.

12. War Horse (2011)

Starring: Jeremy Irvine, Peter Mullan, Emily Watson, Niels Arestrup, Tom Hiddleston, Benedict Cumberbatch, Celine Buckens, David Thewlis, Toby Kebbell

Written by: Lee Hall and Richard Curtis (based on the novel by Michael Morpurgo, and the stage play by Nick Stafford)

If Spielberg spent the 2000s exploring his limits as a filmmaker — both in aesthetics and in subject matter — then War Horse represents his return to the sturdy traditionalism that has informed all of his live-action films so far in the 2010s. I mean it as a compliment when I say that this movie could have emerged from the filmmaking palate of director John Ford (The Searchers, The Quiet Man, The Grapes of Wrath), one of Spielberg's biggest cinema heroes. It's there in the unnaturally brilliant light that pours over the English countryside; in the inebriated pride of Ted (Mullan), a farmer goaded into overpaying for a thoroughbred at auction; and in the righteous dignity of his wife Rose (Watson) as she pillories Ted over how they will make ends meet. But the profound emotional connection their son Albert (Irvine) forms with that horse, who he names Joey, is pure Spielberg, and it informs the rest of the film as Joey and Albert separate at the onset of World War I.

Once Joey becomes the steed of a kind British officer (Hiddleston), War Horse becomes a kind of equine picaresque, as the grim happenstance of the war leads him to his next adventure, be it aiding deserting German brothers, or delighting a French farmer and his granddaughter, or trudging German artillery up a muddy (and bloody) hillside. It's an inherently corny premise — this one magically resilient horse changing the lives of everyone he meets — but Spielberg is confident enough to embrace its earnestness honestly. You can predict to the second the tears that flow during Joey's inevitable reunion with Albert, but that doesn't make them any less earned.

11. Minority Report (2002)

Starring: Tom Cruise, Colin Farrell, Samantha Morton, Max von Sydow, Lois Smith, Tim Blake Nelson, Kathryn Morris, Neal McDonough, Peter Stormare, Steve Harris

Written by: Scott Frank and Jon Cohen (based on the short story by Philip K. Dick)

Ninety-five percent of Minority Report is pretty near flawless. It's Spielberg's first original, popcorn-y summer movie since Jurassic Park (let's just agree to ignore The Lost World, OK?), and you can feel how eager he is to have some fun on a colossal scale. Every corner of this movie just about bursts open with ideas of what life could look like in 2054: self-driving cars that race alongside buildings, intrusive personalized ads that pop up on every available surface, newspapers that update in real time. Even the way Cruise, as top PreCrime cop John Anderton, uses his hands to scrub through the images of impending murders generated by the "pre-cog" psychics predicted how we now swipe through our tablets and smartphones.

This is not, however, a gleaming future of hope and possibility. The twisting mystery that drives the story — will Anderton murder a man he's never met? — also drives Spielberg to make what amounts to a sci-fi film noir. Every image is smoky, high contrast, and desaturated, as if the lens through which Spielberg sees the world had grown cloudy after spending all those years peering into humanity's darkest corners. But unlike the unforgiving harshness of A.I., with Minority Report, Spielberg also liberates a wicked sense of humor, typified in the deliciously creepy sequence in which Anderton must get an eye transplant from a back-alley doctor (Stormare) and his handsy nurse (Caroline Lagerfelt).

With all of the work spent creating this incredibly well-realized, deeply flawed future, and all of the energy Spielberg invests in imbuing it with a mature moral ambiguity, you would think he would have avoided tacking on a happy ending that is completely at odds with everything that's come before it. The outrage I felt about that ending when I saw Minority Report in theaters has, however, dissipated with time. The rest of the movie is just too damn good.

10. Catch Me If You Can (2002)

Starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks, Christopher Walken, Amy Adams, Martin Sheen, Nathalie Baye, James Brolin, Jennifer Garner

Written by: Jeff Nathanson (based on the book by Frank Abagnale Jr. and Stan Redding)

"Cool" is rarely a word applied to Spielberg's films, but starting with its stylish opening credits, the word fits this true-life caper perfectly. It's maybe hard to remember, but in 2002, it wasn't all that clear what kind of actor DiCaprio would be after his Titanic fame. But in Frank Abagnale Jr. — a teenage con artist who successfully impersonated an airline pilot, physician, and prosecutor before turning 19 — you can see both the prepossessing movie star charm and the wells of unresolved need and ambition that have informed just about every role DiCaprio's taken since. Spielberg seems to know instinctively how to match DiCaprio's boyishness with Frank's yearning to escape his parent's divorce by talking his way into manhood — after all, that is pretty much a metaphor for the arc of the filmmaker's career.

After spending nearly a decade toiling in darkness, Spielberg brings a delightful comic touch to Catch Me If You Can, especially whenever Frank is outsmarting Carl Hanratty (Hanks), the dyspeptic FBI agent obsessed with apprehending him. Their dog-and-cat pursuit keeps the movie churning at a riveting brisk clip, even as Frank's lies become so knotted and numerous that they begin to entrap him. The movie moves so briskly that, just once, it stumbles, after Frank abruptly abandons his fiancé Brenda (Adams) at their engagement party once Carl shows up to crash it. Brenda is a fragile soul — her father (Sheen) disowned her after she got an abortion, so Frank builds himself into the perfect boyfriend to win back her family's good graces. After he leaves, Spielberg skates by the wreckage his deception would certainly have made of Brenda's life. The omission is a sour note in what is otherwise an utterly enchanting confection.

9. The Post (2017)

Starring: Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks, Sarah Paulson, Bob Odenkirk, Tracy Letts, Bradley Whitford, Bruce Greenwood, Matthew Rhys, Alison Brie, Carrie Coon, Jesse Plemons, David Cross

Written by: Liz Hannah and Josh Singer

One of the myriad reasons for Spielberg's career longevity is how timeless his films feel. Even the ones that are set contemporaneously don't really feel "dated" decades later (Robin Williams' giant cell phone in Hook excepted, perhaps), and his best movies speak to themes that stretch well past whatever pressing concerns had been pinging in the world at the time of their release.

So while The Post ranks as one of the most timely films of Spielberg's career — going from script to screen in a breakneck 10 months, in order to engage with the quite immediate pressing concerns of the nascent Trump era — I feel confident that its many pleasures will resonate beyond the harrowing times in which it was made. But even if they don't, The Post still makes for a electrifyingly urgent rebuke of the current presidential administration's dismaying #FakeNews drumbeat, by demonstrating how the Washington Post's publisher Katherine Graham (Streep) and editor Ben Bradlee (Hanks) defied the Nixon administration in order to publish a devastating Top Secret report about the Vietnam War.

Faced with so many stories to tell — what the Pentagon Papers are, how they first leaked to the New York Times, why Graham was taking her company public, why that made it especially vulnerable — Spielberg occasionally has to lean on some clunky hunks of exposition. Mostly, though, he seems exhilarated by the opportunity to capture how whip smart underdogs fight, hustle, scrutinize, and deliberate in order to speak truth to power. The generosity of the filmmaker's attention is on particularly abundant display here, with actors in small supporting roles — like Rhys as Daniel Ellsberg, the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers, and Letts as Fritz Beebe, Graham's right-hand man — allowed ample time to breathe humane life into their characters.

And in Streep's finely crafted work as Graham — some of the very best in her own celebrated career — Spielberg, at 70, not only finds a female character as rich and complex as his many male heroes, he imbues her story of a woman in power literally facing down the patriarchy with the same unabashed sentiment and empathy he's employed his entire career. That he's done this only one other time (in the next film in this ranking) is as much a blot on Hollywood as it is on Spielberg, but at least he's making up for it now with films as rousing as this one.

8. The Color Purple (1985)

Starring: Whoopi Goldberg, Danny Glover, Margaret Avery, Oprah Winfrey, Willard Pugh, Akosua Busia

Written by: Menno Meyjes (based on the novel by Alice Walker)

Of all the movies I rewatched for this ranking, The Color Purple was by far the biggest revelation. When it opened, it was regarded as Spielberg's first "serious" film, insofar as it wasn't steeped in genre tropes and visual effects. For the crown prince of Hollywood, that would have been pressure enough. But this movie was also fraught with what we would call today intersectional identity politics. An adaptation of Walker's fiercely loved and debated Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, it was a rare major Hollywood production — as rare today as it was in 1985 — that predominantly starred black female actors. But Walker’s book had been criticized for making black men into villains, and Spielberg was criticized for softening the lesbian sexual awakening of the film's heroine Celie (Goldberg), not to mention the fact that he and Meyjes were both white men telling a story written by a black woman about black people at the turn of the 20th century in the South. The movie was nominated for 11 Oscars but not for Best Director, it won nothing, and then faded into the background of Spielberg's career.

Watching it 30 years later, all that noise falls away, and what emerges is a deeply affecting story told with extraordinary emotional honesty. Within the film's first few minutes, we're confronted with the hard realities of Celie's early life — at 14, she's already had two children by the man she knows as her father — and as she and her sister Nettie (Busia) fall under the shadow of Celie's new husband Mister (Glover), Spielberg captures the menace men carry when women have no power by subtly shifting between Mister's gaze and how Celie and Nettie receive it. Spielberg can't quite get past the halting, episodic nature of the story — his stitching shows more than once. But throughout the film, his heightened visual palate brings the fear, resignation, and wonder with which Celie sees the world to life; in essence, it feels like Celie is telling her own story back to us.

And yes, when Spielberg pans to wind chimes just as Celie and the sexually liberated Shug (Avery) begin to kiss, it is still not a good moment. But what hits me more are the scenes that come before and after that kiss, as Celie's infatuation with Shug begins to blossom without Celie understanding what is happening, and Shug slowly begins to see Celie for who she really is. Romance has never been Spielberg's strongest subject, but I felt hardwired into the deep connection sparking between these two women and lighting up Celie’s dormant soul. And really, everyone should be talking about Goldberg's performance in this film. She is incandescent, and the journey she takes in this film floors me. It is full of life and human contradiction, and truly one of the best performances ever given in a Spielberg movie.

7. Lincoln (2012)

Starring: Daniel Day-Lewis, Sally Field, Tommy Lee Jones, David Strathairn, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, James Spader, John Hawkes, Tim Blake Nelson, Hal Holbrook, Lee Pace, Peter McRobbie, Gloria Reuben

Written by: Tony Kushner (based in part on the book by Doris Kearns Goodwin)

One of Spielberg's best movies is one of his "least" directed, in that Spielberg is modest and mature enough to recognize that between his actors, his script, and his subject, the only thing he could do is get in this movie's way — so he doesn't. Instead, he holds his takes and grounds the camera so we can drink in the music of Kushner's words ushering from Day-Lewis's transformative performance as President Abraham Lincoln.

Actually, all of the actors are wonderfully layered and rich — from Field as the depressive Mary Todd Lincoln and Jones as the thundering Thaddeus Stevens, to the quiet grace of Reuben as Mary Todd’s confidant and dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley. But it is Day-Lewis’s performance — the first in a Spielberg film ever to win an Oscar — that will, it’s clear, be remembered as one of the Greats, in no small part because it will also be one of the Most Watched: Lincoln is destined to be seen by tens of millions of schoolchildren for the rest of the history of the United States.

As it should! Its depiction of the guile, grit, compromise, and cajoling needed in a functioning democracy — especially for a matter as consequential as the constitutional amendment banishing slavery — feels more urgent than ever. It is the best of what cinema, and Spielberg, can accomplish when depicting human history. Instead of making a living textbook, Spielberg takes our past and makes it into life.

6. Schindler's List (1993)

Starring: Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Fiennes, Embeth Davidtz, Jonathan Sagall, Caroline Goodall

Written by: Steven Zaillian (based on the book by Thomas Keneally)

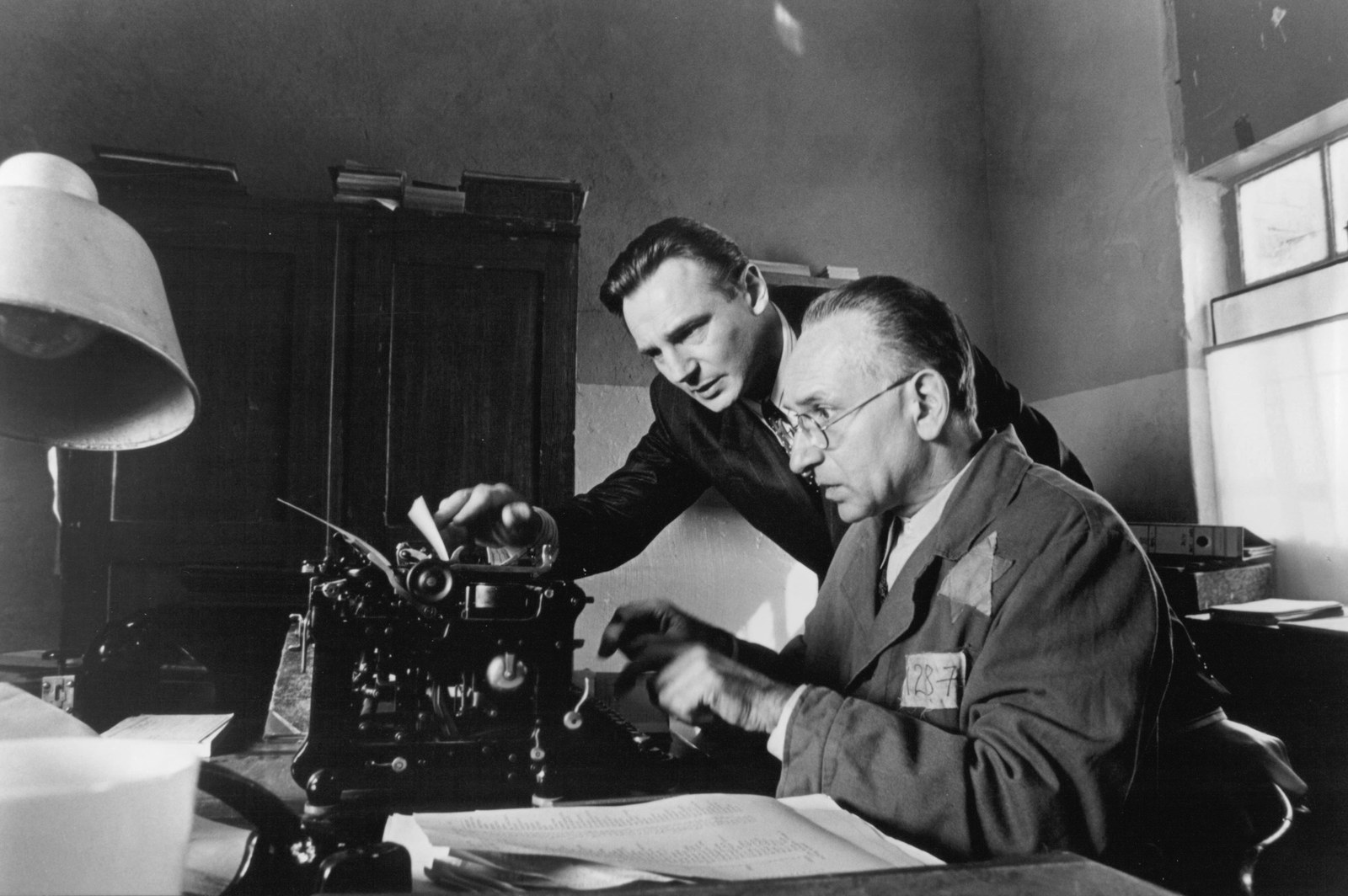

The last time I'd seen Schindler's List was probably in college, and I'd only seen it maybe three times since it opened. And yet, rewatching the film, I realized I could remember every scene, every moment — the one-armed worker's blood seeping into the snow; the doctor euthanizing his patients before Nazi soldiers can kill them; the stampede of mothers racing after trucks of waving children — with an uncanny, sickening clarity. I suspect I am far from alone.

Schindler's List has imprinted itself on our collective understanding of what the Holocaust was, what it looked like, how it felt. Before this film, Spielberg treated acts of violence as an opportunity for cinematic sleight of hand, but here he strips away all the virtuosic artifice he'd mastered in the first half of his career. His camera seems to be everywhere at once, and it does not flinch, from anything, and so neither can we.

My own perception of the story driving those images, however, has changed somewhat. Zaillian's methodical script painstakingly establishes how German industrialist Oskar Schindler (Neeson) built and bought his influence to profit from the war, and how his louche pragmatism brought him inexorably into close contact with his free Jewish workforce — especially his business manager Itzhak Stern (Kingsley). That proximity works on Schindler with such subtle relentlessness that his eventual awakening to their suffering feels to me now more inevitable than tied to any conscious choice or epiphany. Meanwhile, Amon Goeth (Fiennes) — the Nazi officer who reigns over his concentration camp with the sociopathic zeal of a true believer — is held up as a kind of mirror image of Schindler. He also changes with his proximity to the Jews in his camp, especially in his obsession with his Jewish house maid Helen (Davidtz), but it makes him uglier, more bloodthirsty and cruel. As for Stern and the other Jews who make it onto Schindler's eponymous list, they don't really change as much as they diminish. Spielberg keeps returning to roughly a dozen faces to capture how the Holocaust whittles away at their bodies until there is precious little of their humanity left to perceive.

There is a genuine tension in how this specific story about two German gentiles and the Jews in their charge has come to represent the whole of the Holocaust, which isn’t something I think Spielberg ever quite intended. (Indeed, after Schindler's List, he founded the Shoah Foundation, dedicated to finding and preserving the stories of Holocaust survivors.) I understand how some see this film as too hopeful, that Spielberg managed to find a happy ending in one of the most horrifying chapters of the 20th century. But watching it again, I was struck instead by how Schindler changes not because he rises to the challenge, but almost in spite of himself. The Holocaust is truly too big for one movie to define it, but Schindler's List makes plain that it was also too big for any one person to surmount.

5. Munich (2005)

Starring: Eric Bana, Daniel Craig, Ciarán Hinds, Mathieu Kassovitz, Hanns Zischler, Ayelet Surer, Geoffrey Rush, Mathieu Amalric, Michael Lonsdale, Lynn Cohen

Written by: Tony Kushner and Eric Roth (based on the book by George Jonas)

In the opening minutes of Munich, a cell of Palestinian terrorists — men who would go on to kidnap, then kill, 11 Israeli athletes during the 1972 Olympic Games — silently change out of their hiding-in-plain-sight camouflage of athletic warm-up suits and into everyday civilian clothes. It's a strange, unnerving detail, and Spielberg shoots it from afar, as if we're seeing the warning sign no one else in the Olympic Park was privy to that night. It stuck with me.

Much later, the small Israeli team tasked with covertly assassinating the masterminds of the Munich massacre learn that one of their targets is in a guarded compound in Beirut. The team's leader, an ex-Mossad agent named Avner (Eric Bana), forces their government minder (Geoffrey Rush) to let them lead the squad of soldiers needed to take it. As the mission is about to commence, Avner watches bemused as the soldiers ride in on motor boats, race to waiting cars, change out of their special-forces gear and into…everyday civilian clothes. The parallel to the Munich attack isn't perfect — some of the soldiers are in wigs and dresses, to fool the unsuspecting guards — but it's there, and it made me gasp. Then the soldiers take the compound, and as they move from room to room, gunning down men in their homes and bedrooms as their families scream in horror, another parallel hit me like a freight train: Spielberg shoots this sequence with the same handheld, unsparing immediacy as the liquidation of the Jewish ghettos in Schindler's List.

I am not, to be clear, suggesting that Spielberg is comparing a targeted Israeli attack of known terrorists to the Holocaust. But I do think that with Munich, Spielberg means to rattle his audience into feeling the human cost of seeking vengeance after suffering unredeemable bloodshed — and to force us, four years after 9/11 and two years into the Iraq War, to contemplate whether there is such a thing as redeemable bloodshed. Although we track Avner's team, and our sympathies lie with them throughout, Spielberg's empathy in Munich is indiscriminate. He even allows the Munich terrorists their own moments of blinding, human panic.

There isn't another filmmaker alive today with the clout, skill, and fearlessness to attempt this kind of high-wire act at the height of the proverbial “war on terror,” let alone pull it off not as a lecture, but as a gripping, sprawling paranoid thriller. Spielberg uses long lenses and slow-burn zooms to shoot in the midst of everyday life, as Avner's team sweats out each assassination, none of which unfolds quite as planned. But there is no redemption for these men, and I guess Munich’s undertones of mourning kept audiences away: Adjusting for ticket-price inflation, this is one of the lowest-grossing films of Spielberg's career — perhaps that is why it is the only one of his films that I could not find on any digital platform whatsoever. Please seek it out; it may be one of Spielberg's least seen movies, but it is also one of his most essential.

4. Jaws (1975)

Starring: Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss, Lorraine Gary, Murray Hamilton

Written by: Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb (based on Benchley's novel)

I've seen this movie a bajillion times — thanks, basic cable and my idle early twenties! — so rewatching it is an exercise in catching small details. Like, how in the final shot of the film, as Brody (Scheider) and Hooper (Dreyfuss) are paddling back to shore, a flock of seagulls appears to be already feasting on the carcass of the monstrous great white shark that Brody blew to smithereens minutes earlier. I'd never noticed those seagulls before, and yet they do not seem like a happy accident to me. There is a subtle ruthlessness to this entire movie that is a hallmark of Spielberg's career, a willingness to lean into bracing violence that requires a bit of work on our part to put together all the pieces — and makes it that much more chilling for the effort. Like the crabs scurrying over the remains of the shark's first victim, or the shot of Alex Kittner flailing amid a geyser of blood and frothing seawater as children play in the foreground. I mean, in only his second feature film, Spielberg killed a young boy as the incident that launches the film's story, and the gut punch of it still resonates this many bajillion times later.

But if I'm being honest with myself, what does not resonate anymore is the shark itself. It doesn’t look all that convincing anymore; it looks instead like a giant rubber mechanical head. The fright and menace it once inspired — in audiences when the film opened, and in me whenever I first saw Jaws — has dulled with time and technology.

And yet, in spite of all that, the third act still works, because Spielberg's camera is relentlessly invested in Schneider, Dreyfuss, and Shaw's faces as the hunt for the shark rubs their psyches raw. Spielberg gives these actors room to bring rich, beating life into their characters from the first moments they appear onscreen. It is a quantum leap in storytelling maturity from The Sugarland Express, and even though Spielberg famously had to keep his camera on his characters because the mechanical shark kept breaking down, his patient empathy with them is as crystal clear now as the first time I saw the film. Jaws endures as a superlative example of Spielberg’s instinctive, visceral filmmaking, establishing both his preternatural talent for populist cinema and the very idea of the summer blockbuster. But it is our connection to these three men that, in the end, is the reason we keep returning to its foreboding waters again and again and again.

3. Saving Private Ryan (1998)

Starring: Tom Hanks, Tom Sizemore, Edward Burns, Jeremy Davies, Matt Damon, Adam Goldberg, Barry Pepper, Giovanni Ribisi, Vin Diesel

Written by: Robert Rodat

Let's just get this out of the way now: I have always been bothered by the ending to Saving Private Ryan, and it is for a really nerdy reason. The film opens with a World War II veteran (Harrison Young) visiting the Normandy American Cemetery with his family for what we gather is the first time in his life. As he surveys the tombstones, his emotions overwhelm him and he falls to his knees. The camera closes in on his eyes, we hear the roar of the ocean, and Spielberg cuts to D-Day and Capt. John H. Miller (Hanks) as he and his company wait to take the beach.

The ensuing sequence is a landmark of cinema history, a blood-soaked collage of ferocity and chaos that transformed our understanding of combat and irrevocably changed how the movies depict it. When the film opened, I remember this sequence was likened to no less than Picasso's "Guernica," and time has, I think, proven that comparison to be an apt one. And the implication in the film's opening moments is that the old man is Capt. Miller, and that close-up of his eyes is our entry point to his memories of that day.

But at the end of the film, we learn — spoiler alert from two decades ago! — that the old man is actually James Francis Ryan, the private of the title played in the bulk of the film by Damon. But Pvt. Ryan wasn't at D-Day; he parachuted into France beforehand. Spielberg's shot of his eyes and the subsequent cut to D-Day sets up a false connection that irritates me like an itch between my shoulder blades.

I'm dwelling on this because it is pretty much the only bad thing I have to say about this movie. It is a masterpiece, and even masterpieces have flaws, and even this flaw exposes a greater truth in Saving Private Ryan, about how unspeakably difficult the burden of survival is for many veterans to bear. (Of course Ryan would be thinking about D-Day, and how the men who saved him were on that beach.) Throughout the film, Spielberg takes time to soak in how the war has warped and hardened each of these soldiers, and bonded them together. Davies' gentle Cpl. Upham, the translator who joins Miller's unit after D-Day, serves at first as our surrogate into their insular camaraderie — they even mock him for waxing poetic about it. But by the brilliantly staged white-knuckle battle of the film's final act, the war has broken him, too. Spielberg honors these men by honestly rendering their frayed souls, and when they get cut down, we feel the loss to our marrow.

2. Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Starring: Harrison Ford, Karen Allen, Paul Freeman, John Rhys-Davies, Denholm Elliott, Ronald Lacey

Written by: Lawrence Kasdan (based on a story by George Lucas and Philip Kaufman)

I've seen Raiders of the Lost Ark, like Jaws, so many times that watching it now is kind of like going back to my childhood home. The movie is one of our Great Cultural Texts; every second of it has been dissected and reimagined and parodied and interrogated. Most movies could not withstand that constant scrutiny, but Raiders still plays as fabulously well today as it did in the 1980s — actually, it plays even better. Spielberg's confidence in his storytelling, and in Ford as an actor and star, allows him to build Indy into a paragon of heroism and masculinity without the safety nets of self-aware irony or punishing self-doubt that have become common currency in Hollywood leading men. But what makes the character so great is that he is also so human: He sweats, stumbles, bleeds, and gets freaked out by snakes just as often as he triumphs.

As the wild variation in quality of the other three Indiana Jones movies can attest, however, a great character can only do so much on his own. Raiders boasts a tantalizing MacGuffin in the Ark of the Covenant. Its antagonist, Dr. René Belloq (Freeman), is an amoral French archeologist (the worst kind!) with a Bond villain name and a long and unpleasant history with Indy. Belloq's partners of convenience are, you know, Nazis, and they have flying wings, submarines, and deeply creepy stooges who like round wire-rim glasses and torture. And in Marion Ravenwood (Allen), Indy has a true romantic counterpart, a spitfire who can hold her drink and man a machine gun — when she tells Indy, "I'm your goddamn partner," she means it in every sense of the word.

Spielberg orchestrates each of these elements in set piece after outrageously entertaining set piece with an effortless flair that always feels exactly right. (He even takes the time to show Indy doing actual archaeology as he calculates the location of the Ark in the Well of Souls.) What I am saying is that Raiders of the Lost Ark is a perfect movie. I could watch it every year for the rest of my life and never tire of it — and I most likely will.

1. E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Starring: Henry Thomas, Dee Wallace, Robert MacNaughton, Drew Barrymore, Peter Coyote

Written by: Melissa Mathison

Every time I see E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, there is a moment when I begin to cry, and I pretty much don't stop until the movie is over. It's usually when Elliott (Thomas) — a 10-year-old kid with newly divorced parents and no real friends — brings E.T. into his bedroom and breathlessly introduces him to all his toys, which is to say, to his world. And we see E.T. — a feat of practical puppetry that seems as magical to me now as it did in the '80s — take it all in, absorbing Elliott's enthusiasm and wonder even if he doesn't yet fully comprehend it. It is a simple scene, but it is fundamental to what makes Spielberg, Spielberg. As he captures his characters bridging the seemingly impossible divide between them, he closes the emotional distance we feel with what is happening on the screen. And cue tears.

E.T. is Spielberg's greatest and most sustained act of empathy, in part because empathy is how E.T. communicates. "Damn it, why don't you grow up and think how other people feel for a change?" Elliott's brother, Michael (MacNaughton), yells at him after Elliott makes a cutting remark about his absent father to his mother Mary (Wallace). You could see E.T. as a fable about how Elliott learns to live up to that provocation by connecting so fully with E.T.'s emotions that they essentially become the same being. You could see E.T. as a spiritual parable about early '80s suburban ennui, with E.T. as a not-so-subtle Christ figure who teaches us how to feel again. Or you could see E.T. as a simple, heartrending adventure tale about a boy and his alien.

All of these readings are equally valid! Spielberg operates with such enormous pure feeling that it allows us to see what we need to see in the film. As a kid, of course, I connected most with Elliott, and, to be honest, his sister, Gertie (Barrymore), whose initial fear of E.T. gave me permission to be terrified of him too. As an adult, I find myself relating more to Michael's confusion and worry over how best to protect and support his brother, and to Mary's distracted exasperation with how to deal with her kids.

I've abstained from mentioning John Williams in this ranking because if I did, pretty much every entry would have included a variation on the sentence, "And John Williams' score is amazing." But seriously, John Williams' score for E.T. is amazing. It taps into Spielberg's emotional generosity so seamlessly that hearing just a few notes from it now unlocks my tear ducts faster than just about anything.

Listen — any ranking is subjective, and my choice of E.T. as Spielberg's best movie is highly so: This movie overwhelms my senses more than any film I've ever seen. It fills up my heart, inspires my mind, and piles my lap with a small mountain of tissues. It is the reason, really, that I go to the movies.

UPDATE

This story has been updated to include an entry on 2017's The Post. A previous update added an entry for The BFG.