The original version of this story, published Sept. 2, 2013, did not include any comments from actor Tim Curry due to a stroke he suffered in 2012. Curry has since recovered enough to speak with BuzzFeed News about his memories of Clue — in this updated version of the story, all quotations from him and recollections credited to him are from an interview conducted with Curry in Nov. 2015.

When I was 11 or 12, I stumbled upon a mystery that has stayed with me my entire life. It was the early 1990s. I was idly channel-flipping while hanging with friends on a lazy summer evening. At some point, I came across a movie set inside an old-fashioned New England mansion packed with adults in fancy party clothes racing around and screaming at each other. One was dressed in a tuxedo and speaking with a rapid singsong British accent so instantly amusing, I put the remote down just to see what the heck was going on.

After maybe five minutes of madcap banter and murderous revelations, someone in the room said, "Wait, I think this is based on Clue? Like, the board game?"

We were all entranced. The very idea that someone could make a movie based on a board game was just so tremendously silly that even though we barely understood what was going on, we could not tear our eyes away from it. What was this movie? And how was it possible we never had heard of it?

When we got to the movie's three different endings — each resolving the whodunit murder in different, increasingly loopy ways — we all knew we had just seen something unlike anything we'd seen before, and we had to watch the whole thing, immediately. One emergency trip to Blockbuster later, and a lifelong love affair with Clue was born.

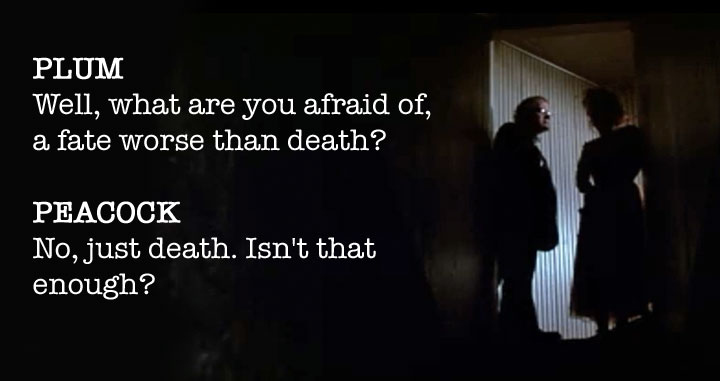

I am far from alone, but as is the case for so many movies with devoted cult followings, you either get Clue or you don't. For 20 years, whenever I have declared the film as one of my favorites in mixed company, one of two things happens: One, the conversation is seized with a mutual recounting of favorite lines and exchanges written by first-time writer-director Jonathan Lynn, matched with breathless impersonations of Tim Curry as the officious butler Wadsworth; Michael McKean as the closeted State Department employee Mr. Green; Madeline Kahn as the possibly mariticidal widow Mrs. White; Christopher Lloyd as the horndog psychiatrist Professor Plum; Lesley Ann Warren as the Washington, D.C., madam Miss Scarlet; Martin Mull as the blowhard war profiteer Colonel Mustard; Eileen Brennan as the batty senator's wife Mrs. Peacock; and Colleen Camp as the buxom French maid Yvette.

Or, two, I am greeted with a gaze akin to if I had proclaimed monkey's brains to be my favorite recipe: Really? You love that?

To be fair, when Clue opened in theaters on Dec. 13, 1985, it was an unambiguous flop, ultimately grossing just $14.6 million (or $31.8 million adjusted for inflation). It was also massacred by most critics, many of whom were dismayed by the then unprecedented — and, for the time, scandalously crass — notion of basing a feature film on a popular family board game. "Fun, I must say, is in short supply," sniffed Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times, while Janet Maslin of The New York Times bemoaned, "there is so little genuine wit to be found in Clue." Not helping matters: those multiple endings. While they play back-to-back now on cable and home video, they were separated out for the movie's theatrical run — one theater had ending "A," another ending "B," and so forth — a marketing gimmick that became the most common target of critics' scorn.

Yet today, Clue is a true cult sensation, a prime example of how a discarded scrap of Hollywood commerce can, through the transubstantiation of time and word-of-mouth, become one of the most beloved films of the 1980s. But why? I rounded up as many of the movie's main players as possible to unravel the mystery of Clue.

I'm going to tell you how it was all done.

The Sixth Time's the Charm

Jonathan Lynn greets me in a posh Los Angeles mansion that belongs to a friend, bedecked not in a tuxedo (as I had hoped), but slightly ripped Levis and an untucked dress shirt. At 70, with a bright white, close-cropped beard and black-frame glasses, Lynn is the sort of polite, witty, avuncular Englishman one would expect to be a little flummoxed wrangling his host's large, friendly dogs as he guides me to a well-appointed sitting room that I immediately decide is called "the study."

With the dogs safely sent away, Lynn explains that he's in town to direct a stage adaptation of the British TV series Yes Prime Minister. That show was itself a spin-off of Lynn's first success in television, Yes Minister, a keenly observed political satire in the early 1980s that was said to be a favorite of Margaret Thatcher's. It is also the reason we're even having this conversation. By the end of 1983, Lynn — at the time, a former actor turned theater director and TV scribe — was hitting something of a career high after the show's three-season run. Still, he says he was surprised when his agent informed him that hotshot Hollywood producer Peter Guber (Midnight Express, An American Werewolf in London, Flashdance) was in London and wanted to have breakfast.

Lynn barely had a chance to sit down at their meeting before Guber declared, "I've got just the project for you — Clue!"

"He's the only person I've ever met who can talk without apparently breathing for minutes at a time," says Lynn. "He was immensely entertaining, and why he decided after about three minutes that I was the perfect person for this, I didn't know." Despite Lynn's protestations that the board game Clue, you know, "has no story," Guber plowed ahead with his spiel: In his capacity as an executive producer, he wanted to hire Lynn to adapt Clue into a screenplay for director John Landis (Animal House, The Blues Brothers) and producer Debra Hill (Halloween, The Dead Zone). Before Lynn realized it, he'd agreed to fly to Los Angeles at Guber's expense to meet with Landis and Hill and hear the full pitch. "Frankly, the reason I said yes was because I'd never flown first class," he says, "and I thought that would be really interesting to do that once in my life."

If Lynn was impressed with Guber's Hollywood panache, he was bowled over by Landis, who had already roughly worked out the major outline of Clue's whodunit plot — six strangers, all blackmail victims, are invited to a mysterious dinner party at a large mansion and assigned color-based pseudonyms; their host and putative blackmailer, Mr. Boddy, is murdered, followed by the cook, and several other visitors; and the guests, suspecting one another, work with the butler to figure out who the killer is — and acted it all out for Lynn. "He was careening around the office, jumping up and down on the furniture, standing on the table, shouting, screaming," says Lynn of their meeting in L.A. "It was a tremendous pitch. I've never seen anything like it in my life." When I ask Landis about this meeting, he just chuckles. "You know, Jonathan's so British, he probably thought, Holy shit, this guy's very enthusiastic."

Landis' enthusiasm was doubly impressive considering that by that point, he'd been giving this pitch for a few years. When Hill, who had secured the movie rights, first approached Landis about directing the movie, he didn't flinch at the fact it was based on a board game. "It was the classic murder-mystery setup with a bunch of characters," says Landis. "I just loved the idea of playing it as farce." But after working out a treatment for the film's plot and central mystery, Landis also realized he'd hit a particularly troublesome wall. "I didn't have a solution," he says. "I went to the point when the butler said, 'I'm going to explain what happened,' like in the classic Charlie Chan/Hercule Poirot/Agatha Christie kind of way. And I couldn't figure it out. I set up a crime I couldn't solve. So I thought, Well, I gotta get a real writer."

He first turned to playwright Tom Stoppard, whose 1968 play The Real Inspector Hound is a delightful deconstruction of the very notion of the murder mystery. Landis says Stoppard toiled on a script for Clue for a full year — and then he hit a wall too. "I'll never forget it," says Landis. "I got a letter from him, literally a year later, on this beautiful onion-skin paper, very elegant stationery, basically saying, 'I give up!' And he enclosed a check for the entire amount he was paid!" (The ordeal must have been quite painful for Stoppard; when I reached out to him for comment, he said via email, "I remember John Landis of course, but I can't remember Clue. I don't think I worked on it. I've never heard of Clue. Sorry not to be able to help.")

Undeterred, Landis next approached Stephen Sondheim — yes, the famed musical theater genius — and Anthony Perkins — yes, Norman Bates from Psycho — to write Clue. Landis had been a great admirer of a 1973 "Hollywood pastiche" murder mystery the two had written together called The Last of Sheila. "Oh, it's terrific!" he booms. "It's bitchery of a high level, as are Stephen Sondheim and Tony Perkins. Besides being great friends, they were also real mystery buffs. I had a couple of absolutely riotous lunches with them. They got very enthusiastic and they really wanted to do it, and then they asked for some outrageous amount of money, and Paramount said, 'Who do these people think they are?!' And I remember saying, 'Who do they think they are?! It's fucking Stephen Sondheim! He wrote GYPSY!' Anyway. They said no." (Perkins died in 1992 from complications due to AIDS; a rep for Sondheim did not respond to a request for comment.)

Eventually, five writers later, Landis remembered loving Yes Minister the last time he'd worked in London. "It's a very clever show," he says. "They were really little mini-masterpieces — textbook construction." But once the thrill of the meeting wore off, Lynn realized that there still was no story.

"There were still a lot of unrelated actions that would have been interesting had there been an explanation, and a lot of characters who weren't characters, they were just colors," says Lynn. "And so I went back to my hotel room and phoned my agent and said, 'This is a total waste of time. Why don't I come home now?' And he said, 'Well, now you're there — why don't you just try and think of something?' I stayed up half the night and sort of had a few tentative ideas, and I went in to see John the next morning and mentioned them. He got very excited about it, and by the time we'd had the second conversation, he said, would I like to write it?"

Over the next six months, Lynn worked on the script back home in England, sorting out how to craft a reasonably coherent story out of all the elements of the board game he was required to include: The color-based character names; the murder; the murder weapons (the lead pipe, the candlestick, the dagger, etc.); the multi-roomed mansion (the study, the ballroom, the kitchen, etc.); the secret passages. While Lynn says he actually enjoyed "the intellectual challenge" of his mandate for the script, he still found himself at a loss for how to properly explain what he was attempting to write to his friends. "They just looked at me as if I was mad," he says with a chuckle. "They just didn't quite know how to respond — and frankly, nor did I."

Perhaps it was Landis' final mandate that kept all those other writers at bay: Create four separate endings, each of which posited a different killer (or killers), each of which had to make sense with the rest of the movie, and each of which would play in separate theaters, thereby giving audiences a different experience each time they'd seen the film. "Landis thought it would be really great box office," says Lynn, who ended up scotching the fourth ending during production because he didn't think it was strong enough. "He thought that what would happen was that people, having enjoyed the film so much, would then go back and pay again and see the other endings. In reality, what happened is that the audience decided they didn't know which ending to go to, so they didn't go at all."

A Silly-Ass Story

Halfway through 1984, Lynn finished his screenplay, which he decided to set in New England in 1954, drawing heavily from his friendship with screenwriters who'd been blacklisted during the McCarthy era. Those daft color-based names were now pseudonyms for Washington, D.C., types who were being blackmailed at the height of McCarthy's power. "I had to find a way to make sense of a situation in which there were a whole lot of people with obviously false names," says Lynn. "I knew all about McCarthyism because I had friends much older than me who'd been involved in it. That was the period of American history that I knew most about." The guests had been mysteriously invited to a dinner party, where each of their transgressions would be revealed and Mr. Boddy, their blackmailer, would be exposed. At least, that was the plan.

To Lynn's great surprise, Landis, Hill, Guber, and Guber's producing partner Jon Peters all loved the script. Not only did it satisfy all of Landis' requirements, it was teeming with screwball one-liners and rapid-fire repartee. A very small sampling:

There was just one snag: In the time Lynn took to write the script, Landis had agreed to direct the Cold War comedy Spies Like Us. In today's Hollywood, a big-name director dropping out of a movie that has no major stars attached to it would have likely signaled the end of the project. Instead, Landis simply asked Lynn if he wanted to take on the directing duties himself, with Landis becoming an executive producer. "He worked so hard and he was passionate about it," says Landis. "He had this amazing [theater] background, and I thought, Gee, you know, why don't you do it, because it will be more than a year before I'm even available."

"Of course, anyone who's been a theater director would like to be a film director," says Lynn. "I didn't have an ambition to direct something like Clue, but when somebody offers you a movie to direct, by and large, you say yes. If it's the first time you've had such an offer, it may be the last time."

After getting a thumbs-up from Paramount Pictures chief Dawn Steel, Landis largely disappeared to make Spies Like Us in Europe and Lynn set about populating his cast. The most important role, ironically, was invented whole cloth by Landis and Lynn: Wadsworth, the butler. While he was writing the script, Lynn had imagined Leonard Rossiter (Oliver!, Barry Lyndon) in the role — they had been working together on the dark comedy Loot in the West End of London at the time. "One of the funniest men I've ever worked with," says Lynn. "Unfortunately, he dropped dead in the middle of act one of Loot. Awful."

With the unfortunate loss of his first choice, Lynn then tried to cast Rowan Atkinson, who was making a splash in Britain with the BBC comedy series Blackadder but was still a virtual unknown in the U.S. (Atkinson didn't debut the character best known to most Yanks — Mr. Bean — until 1990.) "They'd never heard of him and absolutely weren't interested," says Lynn. "He sent a tape of him doing lots of sketches and funny things. I don't know if they watched it."

Finally, Lynn turned to Tim Curry. Already a cult hero from his role as Dr. Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Curry clearly had the theatricality the role required, and a satisfactorily high enough profile for the studio. As an added bonus, "I'd known Tim forever," says Lynn — they had gone to boarding school together.

“He was my hero,” says Curry. “He was the big actor. … I was so happy for him that he had been given a film to direct and write. And I wanted to be a part of it.” Until this interview, however, Curry was unaware that Rossiter and Atkinson had been approached before him. “Both would have been wonderful,” he says.

Most of the rest of the cast, however, were Lynn's first choices, like the late Eileen Brennan (The Sting, Private Benjamin) for Mrs. Peacock and Christopher Lloyd for Professor Plum. Lloyd's breakout movie role as Doc Brown in Back to the Future had yet to hit theaters, but Lynn knew him from his role as "Reverend" Jim Ignatowski on Taxi. More to the point, says Lynn, "He made me laugh when he came to read. That's the way I select people."

For the cast, part of the attraction was to Lynn's screenplay. "The jokes were making me laugh out loud," says Michael McKean, cast as Mr. Green after making his name on Laverne & Shirley and in This Is Spinal Tap. "I thought, Yeah, they made this into a real story — a silly-ass story." As we discuss the movie over French fries at a Los Angeles diner, I ask him if he found the idea of basing a movie on a board game to be crass or silly. McKean waves me off. "There's a very good movie called The Set-Up, Robert Wise boxing picture, which is based on a poem that's barely one page long about a boxing match," he says. "You could make a good movie or a shitty one, based on anything."

This was a common sentiment, bolstered by the sentimental memories of the game itself, which was first invented in 1949 and became popular in the ensuing decade. "I was familiar with the game," says Christopher Lloyd. "I played it some. I thought it was a very intriguing idea."

Martin Mull (Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman and Fernwood Tonight), who landed the role of Col. Mustard, adds, "It just seemed like, Oh, what a hoot. I remember playing Clue as a child, so I was very sanguine about doing the thing — especially when I found out who else was in it." Lloyd was also thrilled with the company he was keeping: "It was a hardcore group of real actors who had a lot of work behind them. I felt like kind of a beginner. I was just hoping I could hold up my part well enough to blend in."

They aren't blowing smoke: At that moment in their careers, these actors were either exciting up-and-coming comedic talents or already well-established and respected comedy veterans — no one more so than Madeline Kahn. Originally, says Lynn, the role of Mrs. White "had somehow come out underwritten" in his first draft. But when Kahn — whose performance as the unenthusiastic German burlesque performer Lili Von Shtupp in Mel Brooks' Blazing Saddles is one of the great comedy turns of all time — "expressed interest" in playing her, Lynn enthusiastically wrote more material for the character. (Kahn passed away in 1999 from ovarian cancer.)

Colleen Camp, by contrast, says she had to fight to stake her claim to the role of the French maid Yvette, who ends up playing a crucial role in the movie's ever-twisting plot. "Jennifer Jason Leigh, Madonna, Demi Moore — a lot of actresses were really interested in this part," claims Camp (Apocalypse Now, They All Laughed). "And I really wanted it." And so she went into the audition dressed in a rented costume as a French maid. "I just found her hilarious," says Lynn. Did Camp's considerable décolletage play any role in casting her? "Not really," says Lynn. "I mean, the bosom is there. There was no avoiding it."

The only time Lynn really compromised on casting was in giving the role of Mr. Boddy to Lee Ving, who at the time was the frontman for the punk rock band Fear. "The studio wanted him," says Lynn. "He had some big hit record or something. I had imagined somebody rather different, but I said no to every one of the studio's requests, and so finally I thought, Well, I'd better say yes to something." (Ving declined a request to be interviewed for this story.)

Like Trying to Herd a Bunch of Puppies

So Lynn had his main cast, and for Miss Scarlet, he landed the biggest star of the lot: Carrie Fisher. A week before rehearsals were supposed to start, however, Lynn got a call. Fisher was in rehab. "I was very naive," he says, eyes wide. "I didn't know what she was talking about. When I met her at a restaurant, she had actually fallen over a chair, but I had just thought she was shortsighted or something. She sniffed a lot, and she said she had hay fever, which of course I believed."

But even Lynn knew enough to be skeptical when Fisher said she still wanted to do the movie. "She said, 'Oh, yes, they'll let me out during the day and I'll just come back at night,'" says Lynn. "And I thought, Really? So I asked [producer] Debra Hill, and Debra said, 'Yes, that sounds good.' I think Debra was also on cocaine, but I didn't know that. Then it was put to Dawn Steel, and she didn't seem to have a problem with it. I didn't know that everyone in Hollywood was snorting cocaine. I was really naive. They weren't doing that in Hampstead, where I lived. Then the insurance company got involved and said, 'Absolutely not. What are you thinking?!' — which surprised everybody but me." (Hill passed away in 2005, and Steel passed away in 1997, both from cancer. A rep for Fisher said she was unavailable for comment.)

To find a new Miss Scarlet, Lynn and Hill turned to Lesley Ann Warren, who had recently earned an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress for her performance as a vivacious gangster's moll in Blake Edwards' musical comedy Victor Victoria. "When I first heard about [the role], I was actually on vacation with my family," says Warren. "I didn't know anything about the board game. I truly was uninitiated."

As it happens, for Eileen Brennan, who died in July 2013, Clue was one of her first projects after a six-week stint at the Betty Ford Center for an addiction to painkillers following an incident two years earlier in which she was hit by a car. (According to a story about the accident in People, Brennan suffered "smashed legs, a fragmented jaw, a broken nose, [and] an eyeball wrenched from its socket.") "I had a lot of sympathy for her because she was still struggling," says Lloyd about Brennan. "She was working very hard to get back on her feet and be able to work again. Not that it showed in her performance at all. But I could see the effort it took for her to get up and do what she was doing. I thought she was absolutely marvelous."

Before anyone in the cast could dive into production, however, Lynn brought everyone onto the Paramount lot to screen the classic screwball comedy His Girl Friday. "He wanted us all to have that cadence, that very clipped, quick delivery on our lines," says Warren.

Adds Camp, "I remember Eileen Brennan barked out at the end of the film, 'Well, you can tell this was before the Method. They just talked!'"

What Lynn couldn't know then was that from that moment, his cast fell into an easy, buoyant camaraderie that rivaled their on-camera hijinks. "I felt so deeply sorry for Jonathan because we were in hysterics the whole time," says Warren. "It was like trying to herd a bunch of puppies."

"Sometimes you're in a movie with someone," adds Mull, "you say, 'Oh, good, I'm going to be with so-and-so in this film.' Then you find out that of the 32 scenes you have, four of them are with that person, and nothing else. In this case, we were always all together, and it just made it so much more fun."

The film's only real set — a mansion that ate up $1 million of the film's $8 million budget, according to Lynn — also helped to keep everyone together. "It was almost the way I pictured movie sets when I was a kid," says McKean. "It was like they'd build a big house inside the stage." With so many open areas during filming, the actors naturally gravitated to the billiard room to pass the time between camera setups. "When we were first there, it was slightly off," McKean says. "All the balls would roll down to one end. We immediately got the experts to shore it up, so we had a real billiard table."

And like that, it became the hottest pool hall in Hollywood. "Every time we'd have even five to ten minutes down," says Mull, "all the guys, and the girls too, would end up in there and just banter around the pool table."

Well, not all the girls. Thanks to her skintight dress and costume designer Michael Kaplan's insistence that the women wear period undergarments — i.e., boned corsets — Warren's freedom of movement was particularly limited. "To rest in that dress was a challenge, so they had slant boards," she says. "It's a diagonal board that one can lean against. It's not uncomfortable, and there are armrests, but you can't sit down all that much. I spent a lot of time there. I didn't play pool."

For her part, Camp adored the French maid outfit created by Kaplan. "The genius of Jonathan Lynn was that he was able to use the assets of each person," says Camp. "I think it was so obvious that I was so well endowed that it became a perfect thing for the characters to react to my breasts." If Camp has anything resembling a regret with the role, in fact, it's this: "Why didn't I take one of those costumes home?!"

The crew found ways to have some fun as well, like when it came time to shoot the sequence in which a crystal chandelier was to fall just behind Mull's Col. Mustard. "The prop master, who was in charge of having the thing drop, also does, I guess, a very, very, very good drunk," says Mull. "He came up to me, right before we were going to do the thing, acting quite a bit tipsy, and said, 'Gah, hope to guh 'is goes ah right.' Scared the shit out of me. I thought, Oh no. No, no. This is no way to go out."

Ironically, when I bring that scene up with Lynn, he laments that he was actually too cautious. "I screwed that up, I think, because I was so frightened that there would be some accident," he says. "It should have only just missed them, and it misses them by quite a bit, and that was me not having the nerve or the confidence to trust the stunt coordinator." Lynn thinks his circumspection was largely due to the fact that John Landis was embroiled in the legal fallout from the death of three actors, including two children, from his directorial segment in 1983's Twilight Zone: The Movie due to a catastrophic helicopter-related accident. "The last thing in the world that could have happened on this picture with him as the producer could have been an accident on the set, so I was being very, very cautious." (When I run this thinking by Landis, while he says he can't comment on the chandelier stunt itself — "I wasn't there" — he is surprised, and a bit touched, by Lynn's caution. "Oh, well that's interesting," he says. "I'd never heard that before, but I understand it.")

In point of fact, while Lynn certainly allowed for a loose and convivial set, he exercised the most control when it came to his script. "Jonathan is a by-the-book guy, and if it was written, that was the way we did it," says Mull. "For Madeline, of course, that's like telling Cicero not to speak, you know what I mean?" Indeed, while most Hollywood comedies today are often largely improvised, all the actors I spoke to said there was really only one time Lynn allowed anyone to significantly break from the screenplay: Madeline Kahn's "Flames on the side of my face" speech.

It lasts only 20 seconds, but for many Clue faithful, this is The Moment, when the movie passes through the threshold from genuine enjoyment to something approaching love — think Roy Scheider saying, "You're gonna need a bigger boat" in Jaws. It comes toward the very end of the film, when Mrs. White is confronted with her hatred of Yvette for sleeping with her husband. "All that was written was, 'I hated her so much that I wanted to kill her,' or something like that," says McKean, still smiling from the memory. "But she just kind of went into a fugue about hatred. She did it three or four times, and each time was funnier than the last. I thought that they could have strung a bunch of them together because they had plenty of cutaways of all of us going, What the fuck is she talking about?"

“I think Jonathan was very uncertain about it,” recalls Curry. “It was very very funny, and hard not to laugh. Flames!”

Needless to say, between the actors' natural talents, and all the concentrated time they spent having so much fun together on set and off, it really is no wonder that they played off each other so well in the film. On the other hand, all that good cheer did occasionally make it difficult for the actors to do their jobs, no more so than for Tim Curry, who often had to unfurl lengthy globs of exposition at the brisk, Howard Hawksian clip Lynn desired. "Tim is a very disciplined guy," says McKean. "Every time when Marty and I would be goofing around — we thought quietly — between takes, Tim would give us a look like, I'm trying to remember the fucking phone book here. And he can give a good look."

Curry doesn’t quite recall that moment. “It sounds a bit pompous to me,” he says with an inscrutable deadpan. But, he admits, “I did have an awful lot to remember.” The entire third act of Clue features Curry practically hyperventilating as he races around the mansion explaining how the murders took place with ever-increasing speed and hysteria. And performing it took a real toll. “I was exhausted at the end of the movie,” he says. “I actually had a sort of incident of high blood pressure towards the end, when all of the conclusions were happening, because I was running around like a mad person. They took me to the doctor and I had to take pills for a week, my blood pressure was so high. Which was very tiresome.”

The rest of the cast did not have much more to do that stand agog while watching Curry’s breakneck acting. "There were an awful lot of instances where it was impossible to keep a straight face," says Mull. "In fact, we were laughing so much, one thing that has stayed indelible in my mind is before every take of every scene, Michael McKean would say to everyone in the cast, 'Something terrible has happened here,' to try to bring us back to the reality of where we were. It got to be quite a funny little catchphrase."

"You're living in a fake world, but you try to make it real," says McKean. "It's not funny if it doesn't mean too much to the people it's happening to. It has to be completely life-or-death.…It became a kind of a comical thing to say, but really, it's that little adjustment. Here's your real life, here's the make-believe part, and we're lucky that we can differentiate."

Do You Dare to Rent This Movie?

Hardcore Clue fans have known for years that Lynn scripted four separate endings for the film, but only three made it into the final cut. But when I ask Lynn if he remembers anything about the "lost" ending, his usual genial nature disappears. "No, not a thing," he says curtly. "No idea." When I note that there's some online speculation that the ending revolves around Wadsworth poisoning everyone, he cuts me off. "I have no idea what's reported online, and I have no idea what the fourth ending was," he says. "It's really gone from my memory, and I don't have a copy of the original script."

Curry does remember shooting an ending in which Wadsworth kills everyone, but, he says, “They thought it was too obvious that the butler did it.” McKean says he recalls that the fourth ending involved "most of the cast… being chased by Dobermans," but he isn't sure if they completed shooting the ending or abandoned it halfway through. And Mull points out that having different endings in general is in keeping with the spirit of the game. "My family could sit down and play Clue tonight," he says, "and Colonel Mustard would have done it; tomorrow night, Mr. Green could have done it."

Regardless, for Lynn, it is clear that the subject of the multiple endings still touches a nerve — especially the decision to release the film with the three endings split up into different theaters. "It was a big mistake to release it with separate endings," he says. "Because you only get the pleasure out of all the different endings if you see them all."

In his original pan of the movie, Roger Ebert agreed: "Why doesn't the studio abandon the ridiculous multiple-ending scheme and show all three endings at every theater?" As it stood, Ebert — who had seen all three endings — was at a loss for how to recommend which ending was the best, since Paramount bungled informing film critics which endings corresponded to the letters (A, B, or C) assigned to them in newspaper ads for the movie. Naturally, Lynn lays the blame for the film's failure to connect with audiences at the feet of that botched marketing gimmick, and he's not the only one who feels that way. "People don't want to buy a pig in a pub," says McKean. "They want to know that they're going to get the good ending. There was something overly complex about it. Do I have to see it three times? And what if I get the same ending again?" One small but telling problem with splitting the endings: Kahn's "Flames" speech appears only in the third ending, so roughly two-thirds of theatergoers never saw it.

To be clear, all of the actors say they were happy with the end result. "I knew how much fun I had doing it," says Mull. "And I was surprised that that didn't translate to the audience having so much fun seeing it."

Adds McKean, "There wasn't a thing about [the movie's] lack of success that you could lay at Jonathan's door. I think he made exactly the right movie. I just don't think they knew what to do with it."

Alas, Hollywood certainly seemed to know what to do with Lynn: Show him the door. "I was unemployable afterwards in Los Angeles," he says, slowly running his hands down his beard. Before the film opened, Lynn had already lined up his next directing gig, Steve Martin's modern-day retelling of Cyrano de Bergerac, Roxanne. "Then Clue got a very bad reception, and 10 days later, I was off the picture." (The film was directed instead by Fred Schepisi.)

“He did have a very blank period,” says Curry of Lynn’s stint in movie jail. “I think he was miserable about it. I felt bad for him.”

Two years after Clue opened, Lynn did risk venturing back to Los Angeles while he was working on another TV series in England. When he happened to walk into a local video store, however, he instantly regretted the trip. "I saw Clue on a shelf with nine really terrible movies and a sign saying, Do You Dare to Rent Any of These?" he says, still wincing from the memory. "If I hadn't come up with Nuns on the Run and made it as a British film four years later, I would never have made another movie, I don't think. Certainly nobody here was going to offer me one." Fortunately for Lynn, when a Hollywood studio (20th Century Fox) did finally hire him again, it was to direct My Cousin Vinny, a genuine hit in 1992 that famously won Marisa Tomei an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress.

It was also around that time that Clue started to become a staple for basic and pay cable programmers eager to fill in non-peak time slots with inexpensive movies. "There are no dirty words, there's no toplessness," says Mull. "It's good television programming." A generation of pre-teens and teenagers, too young to remember Clue's ignominious run in movie theaters, were free to discover the film precisely as I had — this time with all three endings playing together.

"Box office success is wonderful, and that's what everyone wants," says Landis. "But as we all know, lots of shitty movies are huge hits, and lots of great movies fail. You know, Peter Bogdanovich famously said, 'The only true test of a movie is time.' That's the best thing about movies — they still exist." Indeed, throughout the 1990s — thanks to good old-fashioned word-of-mouth and the fledgling tendrils of the internet — it slowly dawned on Lynn and his cast that Clue was no longer a black mark on their careers. Quite the opposite, in fact.

“It's got a life of its own now, this movie,” says Curry. “It's a bit of deja vu for me, really, after Rocky Horror. There are really rabid fans.”

"I go to teach at film schools, and there's always someone in the class who says, 'It's my favorite movie,'" Lynn says with a chuckle. "And I think, Well, haven't you seen The Godfather or Lawrence of Arabia? But equally I'm very flattered, of course."

"I'll run into somebody," says Lloyd, "and of all the movies I've done, they may say something about Back to the Future or whatever, but then they make reference to Clue very favorably."

"Recently, somebody did a painting of me from Clue the size of a wall," said Camp. "It's bizarre and great and hysterical."

"All of a sudden, people in their twenties, wherever I would go, all they wanted to talk about was Clue," says Warren. "They want to do the lines for me. Young waiters, they just want to share their admiration and adoration."

Landis recounts the time a class of eighth-graders reached out to him for permission to stage Clue as a play. "I advised them to do it and not ask Paramount for permission — just don't charge money," he says. "It was somewhere in the Midwest. And then I got a very cute home video of the production." When a semi-professional troupe based in Los Angeles made the same request, however, Landis told them to get in touch with Lynn and Paramount. Lynn dropped by the performance and was as astonished with what he was seeing offstage as on it. "The audience knows the entire script!" he says. "I can't believe my ears. [They] sort of shout all kinds of lines, [like] Madeline's speech about the flames. I'm absolutely amazed by that."

There have been midnight screenings of Clue too, all over the country, with "shadowcast" performances of the film in front of the movie screen à la The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Sins o' the Flesh, the group that puts on Los Angeles' weekly Rocky Horror screening, first staged their midnight presentation of Clue in 2002. "We initially just decided to do it because it had a connection to Rocky Horror with Tim Curry," Sins o' the Flesh cast leader Lizabeth Stockton tells me. The event was such a smash success, however, that it became an annual tradition. "We probably do, like, three other movies a year, but Clue is the one movie that we do every single year because we know that people love it. They're gonna come dressed up, and we play music from the '50s, and we have a costume contest. It's great." Their next performance will be this October.

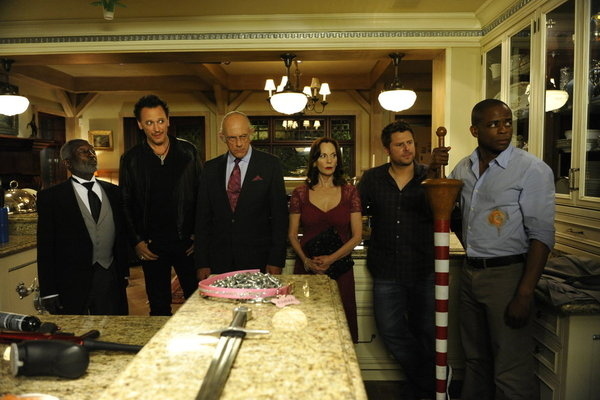

Earlier this year, USA's gumshoe dramedy Psych even celebrated its 100th episode by casting Lloyd, Warren, and Mull in a mini Clue tribute, replete with a zany murder mystery set in a large mansion. "It was one of those movies I always watched on cable," says Psych showrunner Steve Franks. "It's got so many hidden little bits in it that I think it's a movie that grows with appreciation with multiple viewings." Still, Franks says he was initially unsure there was enough of a fan base for the movie to warrant writing a tribute episode. "You look back at the box office the movie generated, and you feel like, Gosh, maybe there's not enough people who know and love this movie to justify doing this — it's gonna be a joke that no one's gonna get." So at Psych's panel at the 2011 San Diego Comic-Con, Franks decided he'd mention offhand that he was developing a possible Clue tribute. "We had a room with like 4,600 seats in there, and I was thinking that 12 people might stand up and get excited," he recalls. "As soon as we said ' Clue,' instantly there was this huge swell of excitement. We're like, 'All right, I guess we'll do this!'"

And then there's this anecdote from McKean: "I was at Elaine's in New York before it closed with Ricky Gervais and his wife, and who comes over to the table but James Lipton. He recognizes Ricky; no idea who I am. Then he introduced us to his wife, who's younger and very beautiful, and he says very proudly, 'My wife is the model for Miss Scarlet in the Clue game.' And he takes out of his wallet a picture of the edition of Clue that had photographs, and it was her. And I said, 'I'm Mr. Green in the movie!'"

The resurrection of Clue over the last 20 years has been understandably sweet for Lynn, who will pop by a midnight screening of the film now and again to answer some fan questions. "I get so much fan mail about Clue, more than anything I've ever done," he says. "More than My Cousin Vinny, more than all my television work in Britain, more than anything. I'm amazed by it."

(Amazingly, Paramount has yet to capitalize on Clue's rabid and visible cult fan base. Last year, the studio's home video division released a Blu-ray edition of the film with zero special features. "I asked my agents and manager to call Paramount and ask if they wanted me to do a commentary or anything," says Lynn. "And they said, 'Nope.' I find it very odd." Paramount never responded to requests for comment, but Landis does offer this dour perspective: "I think the home video market has changed so much that they're really not investing money in it. I'm sorry for John, because it would've been fun.")

While Lynn is basking in his film's late success, however, he hasn't spent a lot of time trying to understand it. "I saw Lesley Ann Warren a few months ago," he says, "and she said, 'People love it now, you know.' And I said, 'Yeah.' And then when I saw Michael McKean a few months ago, he said, 'You know, people like it now.' And I said, 'Yeah.' That's the extent of the conversation. You move on." For Lynn, Clue is simply a part of his past — a delightful part, but not nearly as central in his life as the film remains for fans like me. "If you do anything and people are still enjoying it 30 years later, it's rather miraculous. You can't expect that. I've been lucky."

For the actors, after Clue first flopped, enough time passed before its slow-burn revival that they filed the film away in their memories as a disappointment and forged ahead with their busy and varied careers. Recalling specific details about the movie now can be a struggle — most haven't seen it in years, if not decades. So when I ask what it is about Clue that seems to have captured the hearts of so many of my generation, I am mostly met with well-meaning shrugs.

“I think it's a lot of fun, you know?” says Curry. “There are some very funny people in it. Why else? I don't know. It's not something you can really judge, I don't think. Because in some ways, a film either works or it doesn't, and sometimes it works after it seems to have not worked. … I think it’s a question of people’s sense of humor.”

Adds Mull, "I still get a lot of people saying to me, 'God, I loved you in Clue.' I've done a lot of different films and television shows: Why this one? All I can think of is…it is really one-of-a-kind. There are very few other films I can think of that come anywhere near its structure or the way in which it was made and the way the story is told out."

There is one part of Clue fandom, however, that Mull understands completely: "The only downside to a cult reputation and the resurgence of popularity is that it is so late coming that there's no Clue 2."

It's when I'm talking with McKean, however, that I understand that the answers I have been searching for are no farther than my own geeky childhood. By way of asking him why the movie has become such a hit, I describe that fateful summer evening when my pre-pubescent friends and I discovered Clue. McKean fixes me with a knowing look.

"I have a theory," he says. "It's a movie that is about adult stuff, but you don't need a lot of hands-on experience to know what they're talking about. It's about murder and sex and blackmail, but you don't really get your hands dirty because it's so silly. It's almost like the characters in it were based on characters in a game. Oh, wait a minute!"