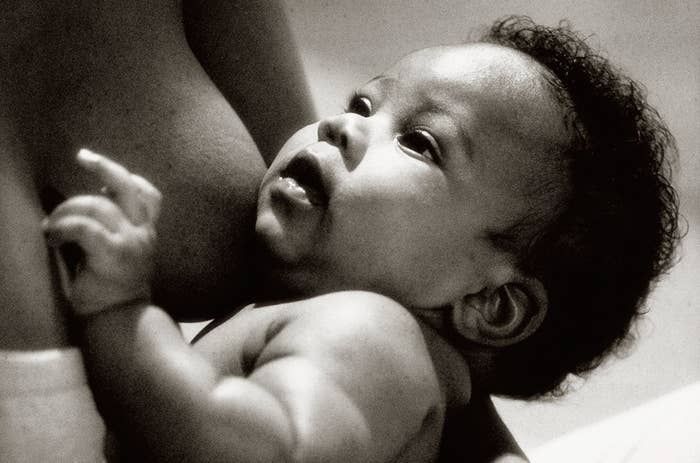

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has hailed the benefits of breastfeeding on the back of some new studies.

The studies are published in the medical journal The Lancet. It says that boosting breastfeeding levels to "near-universal levels" could save 800,000 lives a year, and that breastfeeding prevents various diseases and improves children's intelligence.

Last year, BuzzFeed looked at the evidence behind some of the claims made for breastfeeding. We have now updated it in response to the WHO/Lancet data.

1. There's not much good evidence that breastfeeding makes your child smarter.

We asked Ritchie about the new Lancet/WHO data, and he says it suffers from the same problem.

It's based on a meta-analysis published in the journal Acta Paediatrica, and it found that breastfeeding was linked to a 3.44-point increase in IQ. However, when it looked at studies that controlled for maternal IQ, that increase got smaller – down to 2.62 points. And, most interestingly, the smaller, weaker studies that the analysis looked at were much more likely to find an improvement than larger, better studies. That's often an indicator that the result is a fluke, rather than a real effect. Ritchie notes that the authors of the study didn't do any of the standard statistical tests to rule that out.

"I'd disagree with the authors of the meta-analysis," he says. "If you combine the facts that, a), studies with proper controls for maternal IQ get smaller effects, and b), studies with bigger samples get smaller effects, the breastfeeding IQ effect looks pretty unconvincing."

2. Breastfeeding does protect your baby against infections while it's young.

However, the results are much less clear for the developed West.

The Lancet/WHO study says that breastfeeding "might also protect against deaths in high-income countries", looking at a report published by the US Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. The report itself, however, warns that "one should not infer causality based on these findings".

In Bumpology, Geddes points out that there is good evidence that breastfeeding protects against sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS, which used to be known as cot death. But, she says, the protective effect is small: "5,500 children would have to be breastfed to prevent one death."

3. Breastfeeding probably does make your child slightly less likely to be obese.

4. It's not clear whether breastfeeding protects against diabetes.

"Where it gets more complicated is whether it protects against allergies, diabetes, and things like that," says Geddes. "Some studies say it does, some say it probably doesn't, and the biggest and best studies tend to find no protection."

You'll find people saying that breastfed children are less likely to suffer from diabetes. It's true, but as with the intelligence thing, it's hard to determine whether breastfeeding causes this. Two meta-analyses, one in 2007 and one in 2014, found that there's not enough evidence to draw firm conclusions: "The role of body weight as a mediator or confounder remains uncertain," one says, and "At this stage, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions… Further studies are badly needed on this topic" says the other.

The new WHO/Lancet data, again, is unclear. Although it looked at 11 studies, which, all together, showed some effect, it said that only three of those studies were high quality, and the evidence from those three was not strong enough to reliably show an effect.

5. Breastfeeding protects mothers against breast cancer, a bit.

6. People tend to overstate some of the benefits of breastfeeding.

There have been some dramatic claims made about the protective effect of breastfeeding. The US National Breastfeeding Awareness Campaign (NBAC) used to say that breastfed babies have a reduced risk of ear infections, respiratory illnesses, diarrhoea, and obesity, diabetes, and leukaemia. The US Ad Council claimed that children who weren't breastfed for six months had a higher risk of "asthma, allergies, diabetes and cancer; suffer more colds, flu and other respiratory illnesses".

The trouble is, as we've seen above, it's really hard to tease out the effects of breastfeeding. People who breastfeed tend to be healthier, wealthier, better-educated, and so on than people who don't.

It's also particularly hard for working women to breastfeed, especially those on shift work, and some women find it painful or impossible. As this analysis in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law points out, overstating the relative benefits of breastfeeding risks provoking unnecessary anxiety among non-breastfeeding women.

7. The most important thing is that the mother is healthy and happy.

There are real advantages to breastfeeding, but some of the claims about it are overdramatised and uncertain. And the risks of placing undue pressure on mothers are real, if it pushes them into postnatal depression. "What there is good evidence for is that maternal depression is bad for children," says Geddes. "Depressed mothers find it harder to form a secure attachment with their babies, and the babies have a harder time forming relationships in later life. I don't think guilt is good for mums.

"There are lots of other things you can do boost your child's chances. If you're not inclined to breastfeed, you're not a bad mother."