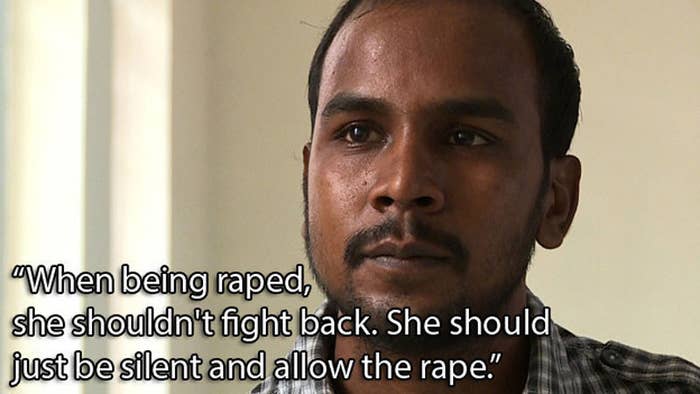

This past March, a British documentary about the horrific 2012 gang-rape and murder of Jyoti Singh, India’s Daughter, was poorly received here at home. As documented by prime-time news and hundreds of headlines, the film was banned from release in India, taken off YouTube following court orders, and forbidden from broadcast anywhere in the nation. The reasons provided were manifold, ranging from its legal ramifications on an ongoing court case to its potential to “incite violence.” Union Minister Venkaiah Naidu said that “an interview which will defame India internationally is totally unacceptable.”

Last week, India’s Daughter filmmaker Leslee Udwin had a chance to discuss that ban with the world watching. Sharing her stage was Barkha Dutt, an NDTV anchor who has been outspoken in her disagreement with the ban. Back in March, NDTV blacked out its channel for an hour in protest of it.

On April 23 in New York City, Dutt—who is known in millions of Indian living rooms as a staunch feminist, a loud critic of India’s shortcomings in its treatment of women, a shouting defender of women’s safety—sat down with Udwin at the 6th annual “Women In The World” conference. They were to jointly answer an ambitious question, “Who’s winning the fight against sexual violence and gender inequality in India?” while moderated by CBS anchor Norah O’Donnell. The discussion lasted no longer than 20 minutes and—as is often the case with such events—raised more questions than it answered. Foremost: As the international media puts a spotlight on sexual assault and harassment in India, how can Indian women reconcile their patriotism with their feminism?

Dutt was uncharacteristically silent and stone-faced when the panel began, watching as the British woman and the American woman on stage with her carried on about internalized misogyny in India, to frequent applause. “Society’s way of coping with the embarrassment, the shame, of what it does to its women is to marginalize [rapists], to try and pretend they’re just rotten apples in a barrel,” Udwin said. “It is the barrel that is rotten. It is the barrel that rots the apple. It is society that is responsible. We all are responsible.”

When she finally did speak, Dutt did not continue Udwin’s indictment of societal misogyny.

Instead, she defended her home. She said:

“I want this audience here to understand today – because I don’t know how many of you have actually been to India – that while hearing about the controversy about Leslee’s film may make you feel that there’s an environment of hostility towards women in India, it’s actually the opposite. What the aftermath of this horrific rape did was to create a moment of hope for women in India. For the first time in my 20 years as a journalist, I’ve seen the issue of gender move from the margins of news to the centerstage of politics. I have seen the mainstreaming of gender as a political issue. [...] This is a moment of hope and that’s what we need to understand.”

As a woman who grew up in India and briefly lived away from it, I understand the emotional imperative to defend my home when it is criticised by foreigners. But after so many conversations about India’s treatment of its women—with Indians and also with non-Indians—I’ve come to the conclusion that my role in those two types of conversations is different.

Being critical of India amongst Indians, our love for our home and the pride we take in it is assumed. There is a tacit understanding that while we can be harsh about the shortcomings of Indian society, we still adore it and owe it everything we are. We are able to have productive conversations about India’s failures because our knowledge of its successes is shared and assumed.

In the latter type of conversation – being critical of India around non-Indians – my commitment to having a productive conversation often takes a backseat and my role as proud spokesperson for a globally misunderstood nation takes the wheel instead. Like Dutt, I forget the virtues of criticizing my home and instead succumb to the irresistible temptation to defend it against outsiders who do not love it like I do.

When O’Donnell then mentioned that “India’s Daughter” made her realize how unsafe India is for women, Dutt launched into another impassioned defense of her home. “I have a fierce disagreement with the narrative that’s being built around my country,” she said, going on to argue that India falls victim to unfair generalizations about its treatment of women.

She drew on statistics to point out that the US and UK have more instances of gender violence than India does. She mentioned that India had a woman Prime Minister four decades ago, contrasting that with the fact that the United States is only now verging on electing a woman. She pointed out that, unlike the USA, India has paid maternity leave, and isn’t having conversations about abortion and reproductive rights.

“Gender is more complex than we think,” she finished, this spirited defense of her motherland landing gracefully on immediate and thunderous applause.

GIFs of that particular exchange have found their way onto Tumblr dashboards and Twitter timelines as a slamdunk shutdown of white feminism. Dutt’s own Twitter timeline is spattered with thank yous sent in response to praise for her articulate defense of India’s reputation. If Twitter chatter and Facebook comments are anything to go by, the few thousand Indians who have seen that exchange have applauded it.

Less rebloggable—but also worthy of discussion—was Udwin’s belated rebuttal. Later in the conversation and in the context of her own film’s ban, the filmmaker charged Indians with silencing honest conversations about our women out of “jingoism and knee-jerk reaction to India’s image.” What went unsaid in her diagnosis of the nation was Dutt’s inclusion in it.

“It’s just misplaced, frankly,” she said. “You cannot take care of your shame and let that trump saving your women. You cannot do it.”

And Dutt agreed, conceding, “There should be no insecurity or misplaced national pride defining this conversation.”

Because Dutt, a journalist, knows better than anyone else that positive conversations are rarely productive ones. The most productive conversations – as demonstrated on her own hugely popular talk show We The People every Sunday night at 8 p.m. – are ones in which we can look our flaws squarely in the face and figure out, together, how to fix them.

If we truly care about improving India’s treatment of its women, there are no benefits to impassioned defenses of it. If we want our home to be more hospitable to half its inhabitants, we stand to gain absolutely nothing from sweeping its flaws under a rug and singing its praises instead. If we are true patriots (in that we truly want a better India), it is counterproductive – albeit both tempting and natural – for us to “fiercely disagree” with its critics.

And yet, Dutt’s defenses of India requires shedding one’s objectivity about which conversations are and are not productive.

In the most productive iteration of this conversation, it would be noted that despite the fact that India has maternity leave, an alarmingly low proportion of Indian women remain in the workforce after having a child and only 27% of females over 15 years old are working to begin with. A productive conversation would ask why. In a productive conversation, it would be noted that while – as Dutt says – India isn’t having the same conversations about abortion and reproductive rights that the United States is, India is instead having conversations about female foeticide. It would be noted that while statistics paint a grimmer picture of sexual violence in the United States and the United Kingdom than they do of India, those numbers are skewed by the fact that marital rape has yet to be criminalized here at home (a battle Dutt herself has been fighting relentlessly at home).

Dutt’s defensiveness—and mine, in similar conversations—is only human nature. It is the adult version of the playground tendency to fly into a rage when somebody else insults our family or friends, whereas we ourselves are allowed to say much worse to and about those same people. We defend our own, no matter what, even if we are otherwise their harshest critics.

The question, per usual, is: so what? What is at stake when this benevolent duplicity occurs on a global stage? When we treat India like our defenseless little sister?

It is infinitely frustrating to me, as it is to any Indian, when our overwhelmingly and shockingly beautiful motherland takes center-stage in discouraging headlines on global front pages. Barkha Dutt demonstrated, as any of us would when placed in the same situation, that it isn’t easy to stand by and watch as the country that we call home is criticised, and even less so when it criticised by outsiders for flaws we are already aware of here at home. But rather than misplacing our pride, we should be earth-shatteringly loud when we celebrate our triumphs – our Nobel peace prize, our successful mission to Mars, our historically massive exercising of democracy. We should not, instead, lose our objectivity about the shortcomings we know we have.

Because what we lose by fixating on maintaining an untarnished global image is the honesty and objectivity required for progress. When someone like Barkha Dutt – a journalist known and revered for her strong, critical stances on domestic issues – turns around and says “nah, it’s not that bad,” we lose some of the vigor we need to battle our demons here at home.