1. The meal was cooked by only four women because all the other women pilgrims had died.

All the food the 140 odd Pilgrims and Native Americans feasted on to celebrate the first successful harvest was prepared by four presumably extremely stressed out women. All the other women on the Mayflower had died by the time fall rolled around. (The pilgrims landed on Nov 21st 1620. The first Thanksgiving was fall of the following year. That first year was ROUGH.)

2. There was probably no turkey.

This is important to address right at the outset — there may have been no turkey. We know there was wild fowl, and that four men brought back enough of it to feed the company for a week, but while this could have meant a whole load of turkeys, it also could have meant a whole load of swans, cranes and quail.

3. There was definitely no pie.

There was no pumpkin pie (they had no butter and wheat flour for the crust; they also had very little sugar), no cranberry sauce and no sweet potatoes. They did seem to have a tuber they called the potato of Canada, which sounds ridiculous, but we can hardly judge considering we now call them Jerusalem artichokes.

4. It was a feast of venison organ meat.

They certainly ate venison, because the Native American hunters (of the Wampanoag tribe) contributed five deer. But we're not talking juicy steaks — picture hearts, kidneys, and brains (the English liked hanging their meat, which took a few days, whereas the organ meats needed to be eaten right away). Otherwise there was lobster, fish, and side dishes made from corn, a few peas, (the pea harvest didn’t work out so well), and squash. Happily, there were definitely gourds. Lots of gourds.

5. Everyone was drunk, even the children.

Most importantly, there was alcohol. Back then, the English considered beer safer to drink than water (often rightly) and as long as it was available, they served it at all meals to everyone, except maybe babies. Just to clarify: Pilgrim children drank beer for breakfast. The early colonists tried making alcohol from carrots, tomatoes, beets, celery, squash, and, most gross of all, onions, but it’s unclear if any of these surely disgusting brews were served for the first Thanksgiving.

6. Most of the Native Americans were also dead.

The colonists lost about half their members that first year, but the Wampanoag had lost even more. A plague, possibly smallpox, had swept through coastal New England before the Pilgrims arrived and killed up to 96 percent of the Native Americans (true to form, the Pilgrims considered this a “miraculous” gift from God). This left the Wampanoag vulnerable to their western rivals the Narragansett, and helps explain why Massasoit, the Wampanog chief, was willing to align with a group of strangers in the first place.

7. Squanto was the most interesting part of the whole story.

The life of Squanto, an English-speaking Native American who was largely responsible for enabling the Pilgrims to survive long enough to celebrate that first harvest, should be optioned and turned into a suspenseful, tragic movie. If you take the most dramatic version, obviously what Hollywood would do, he crossed the Atlantic six times, twice as a captive, escaped from slavery twice and eventually made his way back to his village only to discover he was the sole survivor of his tribe (Patuxet) and the land was now occupied by a bunch of Europeans. Then, naturally, he helped the pilgrims grow their first harvest.

8. The feast lasted three days.

Considering again those four overworked women, the feasting lasted not one afternoon but three days. The Pilgrims were just that pumped about how well the harvest had gone. What they didn’t know was that a few weeks later another ship, the Fortune, would show up with a whole boatload of people pretty much only carrying the clothes on their back.

9. There was entertainment.

Unlike their gluttonous modern counterparts, the group probably did not eat continually eat for all three days. Instead they likely played games like pitching the bar, in which a man would take a bar of metal, run with it, and then throw it. That was the whole game. Or they might have played something called stool ball, an early form of cricket. They definitely shot off their guns quite a bit. Meanwhile the four women stood around and were entertained by all this. (Maybe?) When they weren’t cooking, that is.

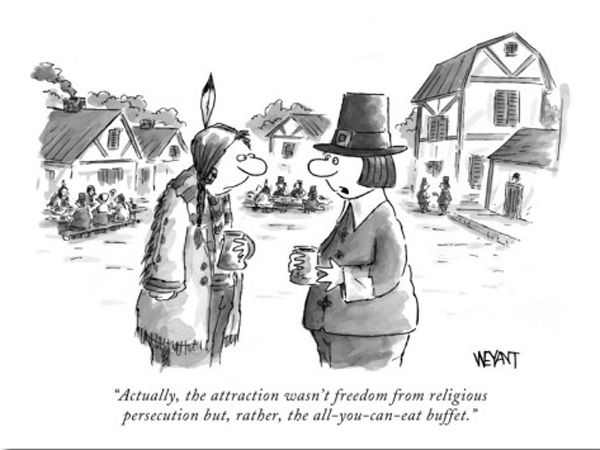

10. Maybe they danced a little.

Of the people who came over on the Mayflower, about half had come because they wanted to break away from the church of England. That half called themselves “saints” or “professors” (though they didn’t mean it in quite the highfalutin way that now sounds) and designated the other rest “strangers.” Unsurprisingly, the “saints” didn’t dance, though the raucous “strangers” might have had private dance parties at their own houses that those killjoys weren’t invited to.

11. It smelled terrible.

Saints or strangers, all the colonists smelled bad. None bathed regularly, as they thought it spread disease. They did wash their hands and faces before meals, but this did not keep the Native Americans from complaining that they stank. Apparently Squanto tried “without success” to teach them to bathe.

12. The pilgrims and Native Americans may not have eaten together.

Running counter to basically every illustrated image anyone has seen of the event ever, there is no reason to think the Wampanoags and Pilgrims ate together. After all, only a few of them could even speak each other’s language. And then there was the smell issue. It's possible the leaders of each group dined at the same table with translators like Squanto assisting in the communication, but what everyone else did is anyone’s guess.

13. We're not even sure the Native Americans were invited.

There isn’t even any evidence the Wampanoags were officially invited. They might have just been celebrating their own harvest, when they often visited neighbors and allies. Or maybe they heard the English “practicing their arms” as they called it back then, and were curious to know why on earth their allies that were making such an unreasonable amount of noise.

14. They didn't call it Thanksgiving.

And they didn’t celebrate so late in November, either. Its modern calendar placement was instituted by Abraham Lincoln when he declared it a nationwide holiday in 1863. He was egged on by a forceful woman named Sara Josepha Hale (pictured above), who carried out an (in retrospect) odd and obsessive campaign to make it a national holiday. (Hale was the author of "Mary Had a Little Lamb"). Lincoln probably set the date to correspond with the anchoring of the Mayflower in Cape Cod on November 21, 1620.

15. In fact we basically know nothing about it.

In conclusion, there are heaps of things we don’t know about the first Thanksgiving. Did someone play the lone trumpet brought over from Europe? Who did all the dishes? And how did one escape the company of one’s fellow man without the parade to watch on TV? There are only two primary sources about what really went down — a letter carried back to England on a ship that was attacked by pirates (but eventually the letter was published), and a first-hand account written 20 years after the feast that was stolen by looters during the revolutionary war, but reappeared in the 19th Century.