If you are shaken to the core of your being by the new Instagram terms of service, you're probably most upset about the section that precisely spells out how Instagram can use your photos and likeness for advertisements without compensating you. The more subtle change in its terms, with a smaller backlash, is this clause:

You acknowledge that we may not always identify paid services, sponsored content, or commercial communications as such.

Instagram can, in other words, show you an ad without telling you that you're looking at an ad.

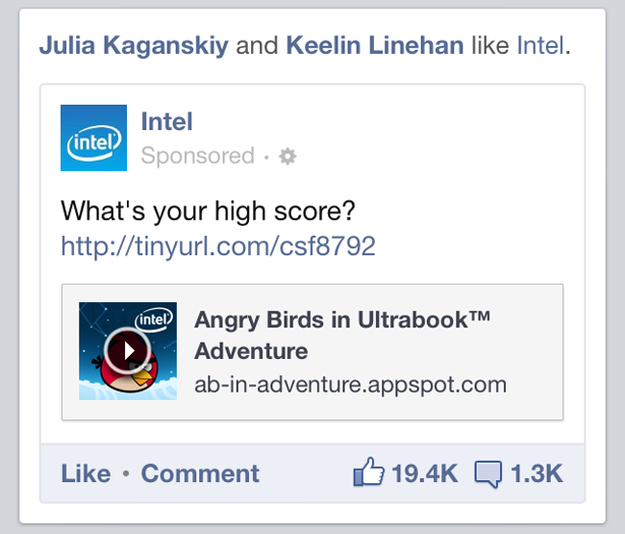

Sponsored content is a bedrock of Internet advertising: blogs, websites, Google search results, YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and a lot of other places your eyeballs wander throughout the day on the Internet. It is a fact of life. The thing is, all of that sponsored content — at least on reputable sites — is clearly marked as such. It can take a few different shapes, though the form of the ad usually precisely matches that of the site's native content, the stuff you are there to see. It might be a straight-up ad written as a blog post on a news site, or simply carefully placed branded content, like a post from Starbucks shoved in your feed on Facebook/Twitter or in a Google Maps search.

But it's almost always labeled something like "presented by" or "sponsored." Even Facebook, which has nearly the exact same clause in its terms of service, stating that "you understand that we may not always identify paid services and communications as such," labels sponsored content. This is a matter of trust: We don't mind looking at ads to get our free Free free content, but we want to know what's real and what's not — a complicated binary, but let's stick with the simple version for now — and our notion of "not real" in this context tends to be things companies have paid to place in front of us. It's not real or natural or organic, and we want it properly labeled. By the same token, respectable publishers tend to believe that sponsored stuff and editorial content should be kept separate both for ethical reasons and to maintain credibility with consumers.

The core reason that sponsored content should be properly labeled is that it's not produced for love or truth; it's produced for money, and to get you to buy things. But let's set that aside and look at another, underlying notion that — at least from the perspective of many in online journalism — sponsored content is less good than real content. And much online advertising has been lower quality than the real goods. Which, if you're savvy a consumer of media, you can often feel if you happen to look at a piece of sponsored content. It's off somehow; it's in the wrong place or it's not quite what you were looking for in a search or not written quite as well.

But what if sponsored content was just as good as real content? What if the sponsored content happens to be exactly what you're looking for, and the quality is just as high as the genuine article? Does it matter to most people, then, that it's sponsored, that somebody paid to put it in front of you?

That's effectively what movie trailers and music videos have been historically — the highest quality advertising, in a sense. And it's been the holy grail of Internet advertising — ads and sponsored content just as good as the real thing. Ads so good that you share them with other people. Cue all viral marketing stunts and the business models for BuzzFeed and Facebook and Twitter and Google so on.

Facebook illustrates just how effectively the lines between content and ad can be and have blurred. It got us to "like" things. Fun! Because of course we like certain movies and music and TV shows and brands. For instance, I adore Jiro Dreams of Sushi and alt-J and Archer and Muji and I have no problem letting my friends know about everything I like. The stuff you "liked" on Facebook, for a long time, was real content; you actually logged onto Facebook to see what your friends listed as their "likes." Now it's an ad unit, and I'm reminded once a day that a person I'm friends with "likes" Starbucks in a sponsored post. Real content became sponsored. More recently, Facebook started presenting users with the power to ensure more of their friends see something they post on Facebook, for a fee. Your friends' Facebook updates are real content! They are the things you go to Facebook to see. But what if your friends are paying a small fee to make sure you see them? They're technically sponsored content, but they're also "real content"?

But Instagram is different than Facebook and the rest of those companies. Paul Ford explained that difference right after Facebook bought it:

Tens of millions of people made a decision to spend their time with the simple, mobile photo-sharing application that was not Facebook because they liked its subtle interface and little filters. And so Facebook bought the thing that is hardest to fake. It bought sincerity.

Instagram is sincere. It's emotional. It's meaningful. And our relationship with it is deeply personal. This is what Instagram has (or had), in part because it never exploited us. It felt safe. Which is a feeling that that no other social network managed to capture, at least not in quite the same way. And now Instagram at last intends to exploit that.

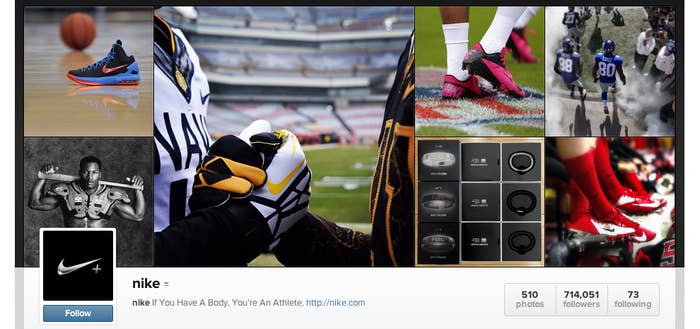

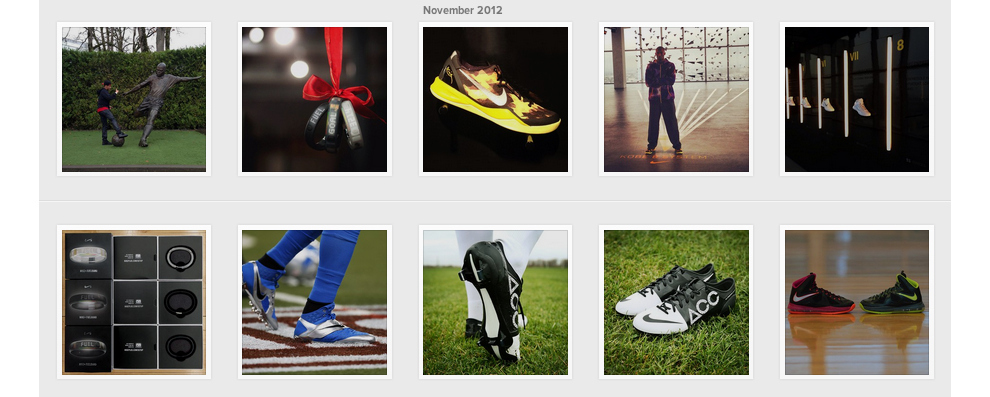

That clause is, in effect, Instagram believing that it can do something better than many other companies, that it can show us sponsored content and it will be so meaningful and beautiful that we truly won't know or care that someone paid to put it in front of us, like Nike's beautiful Instagram page. This goes hand in hand with a deep belief in the beauty of Instagram as a medium, from which it's easy to see how ugly words like "sponsored" or "ad" don't belong anywhere near it. These photos aren't ads; they're Content. And most people practically can't wait to see them.

Update: Instagram has issued a response to the backlash to its new terms of service, assuring people that "it is not our intention to sell your photos." In the context of this piece, about Instagram and advertising, here's what Systrom said that's highly relevant:

Our intention in updating the terms was to communicate that we’d like to experiment with innovative advertising that feels appropriate on Instagram. ...

To provide context, we envision a future where both users and brands alike may promote their photos & accounts to increase engagement and to build a more meaningful following. Let’s say a business wanted to promote their account to gain more followers and Instagram was able to feature them in some way. In order to help make a more relevant and useful promotion, it would be helpful to see which of the people you follow also follow this business. In this way, some of the data you produce — like the actions you take (eg, following the account) and your profile photo — might show up if you are following this business.

Ads you'll love.

(I also clarified a few things above.)