The new Instagram might not look all that different — you might notice it's spiffed up here and there — but it does something pretty radical that the old Instagram didn't: It organizes all of your photos on a giant map. Which, okay, doesn't sound all that nuts. But it's nutsier than you might realize.

In an interview with TechCrunch, founder Kevin Systrom reveals just profound the change is, or at least will be: "We realized that chronological order was not the way we wanted you to browse overall, and we decided that location was more important.”

Even with the update, the primary organizing principle in Instagram is still time. When you open it and go to homescreen, you still see a reverse chronological stream of photos. When you click on a photo in the tab Explore, the major point of metadata you see is how long it's been since the photo was posted; and there's still no way to use the Explore tab to poke around photos taken nearby.

But when you click on a friend's profile — or your own — you'll see the option to check out the Photo Map, which maps out the precise location of every single geotagged photo you or your friend has taken and allowed Instagram to put on the Photo Map. When you fire up the new Instagram for the first time, it'll present a list of every single photo you've geotagged. (Which may be far more than you realized, since Instagram never overtly surfaced geotag data in photos before, unless you checked in to a specific place. Example: This photo is geotagged and shows up on my Photo Map, but you can't see that location data at this link or in an Instagram stream. But in this photo, because I tagged a specific place, you can see where the East River Bar bar is. Plus, once you turned the location option, it stayed on by default.) You can then pick which photos you want Instagram to put on your Photo Map. As Systrom enthuses, it is a genuinely powerful way to experience photos, like "going back into your bedroom and opening your shoeboxes," because of the way it resurfaces older photos that were previously buried at the bottom of a very long river of images. So it might be more accurate to say that, in a way, it explodes the tops off your old shoeboxes, permanently.

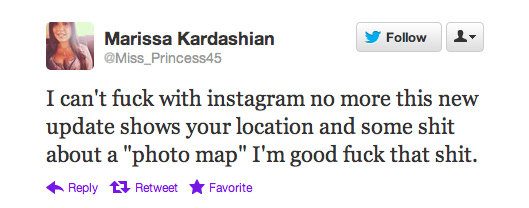

So why create something that intensely cool and kinda bury it in people's profiles? Because location still freaks people out. I know some people think "persons upset on Twitter" stories are like, whatever, but a scan of "Instagram map shit" and general sentiment is revealing.

That creepiness factor is part of the reason that no company's really "cracked" location wide open, despite many, many attempts. Everybody's trying, obsessively, precisely because of how powerful location is as a dimension of data — it's possibly the single most potent signal that mobile offers over traditional desktop computing. Location is more than just where, it's an entire world of context, particularly meshed with other signals. It offers why. In an example Microsoft gave me last year when talking about Bing, if somebody's searching for shoelaces on their desktop, they're probably just looking for something style-wise; if they're looking for shoelaces on their phone, they possible just broke a shoelace and need a new set right now, preferably from somewhere very close by. So the creep factor is part why Instagram's moving slowly with location (and why Systrom is very careful to say that Photo Maps are only harnessing data that was already public).

The other part of cracking location is being able to offer something truly compelling in exchange for that location data — Foursquare trades in deals and recommendations, and it's collected around 10 million users from that. Instagram is trading in emotion. Photo Map is simple and direct. And well, it's hard to offer something more compelling than emotion — which is how Instagram got to 80 million users in the first place.

Systrom told Mat Honan back in February, before Instagram was acquired by Facebook, that "I don't like the idea of Instagram as a photo sharing service, and I don't think it is. It's very much a communication tool, it's a visual communications tool."

I think it's a safe bet that we're beginning to see what that "visual communications tool" really looks like. If a photo's worth a thousand words, I suspect Instagram shots are going to be worth a lot more.