Michelle Whitehouse always just assumed she was an Aussie.

Although she was born in the UK, she came to Australia as a two-year-old in 1963 and has lived here ever since. Her mother and grandparents were Australian-born. Her father, a UK national, obtained Australian citizenship and worked for Ansett Airlines for over two decades.

There’s even more than that. Both of her siblings are Australian citizens. Her three children, born in Australia, are too; so are her six grandchildren. Three of her grandchildren are Indigenous Australians. Until this year it had simply never occurred to Michelle that she was anything other than Australian.

“I came here on my mum’s Australian passport. She’s a born Australian, my grandparents were. It wasn’t something that was thought about,” said Michelle, who speaks in a very broad Queensland-country accent.

It was only when the Department of Immigration and Border Protection informed Michelle she was going to be deported to the UK the penny dropped, after all this time, that she’s not Australian.

The 54-year-old woman’s troubles began in March, when she was convicted of possessing and supplying marijuana.

It was by no means Michelle’s first offence. She says she has a problem with drug abuse, and has been to prison twice, including for drug trafficking in 1997. The bulk of offences filling out her three-page criminal history are fines for drug possession.

But Michelle's history is more complex than a few drug convictions.

Her parents split up when she was four. Guided by government policy at the time, she was institutionalised. What happened during the seven years Michelle was in state care isn't entirely clear - she says her memories have been suppressed.

But what is clear is that the cycle of state care, substance abuse and incarceration is not unique to Michelle.

“I think being institutionalised from four years old has made me a substance abuser. Being in and out of jail all that time doesn't mean anything to me because I've been there since I was four,” she said.

Michelle insists she wasn’t selling the marijuana, but sharing it with a friend. In any case the court had a clear idea of the threat she posed to the community: her sentence was wholly paroled. Rather than spending time in prison, the judge said the grandmother should be given the chance to continue a rehabilitation program.

But while on parole, Michelle failed a drug test, landing her in Townsville Women's Correctional Centre. She was only supposed to be there for four weeks. But the Immigration Department became aware of her conviction and told Michelle it needed to clarify her visa status. On June 18 she was told her visa was cancelled. She was going to be sent to the UK.

“I was quite disgusted that they’d just send her over to somewhere she doesn’t even know herself,” said her daughter Rhiannon Whitehouse. “My mum’s the most Australian person I know!”

Still detained in Townsville waiting for the department to transfer her to immigration detention, Michelle had her first taste of what the next six months would be like: waiting.

Eventually, on August 6, she was removed from jail, 13 weeks after her sentence was supposed to be finished, and was taken to Sydney's Villawood Detention Centre. She’s been there ever since, waiting to be deported.

“I was quite disgusted that they’d just send her over to somewhere she doesn’t even know herself. My mum’s the most Australian person I know!”

“I knew there was a possibility of jail and parole [when I offended] but I didn’t know the outcome would be like this,” said Michelle.

Far from being an extreme story, the grandmother is one of 1,105 residents who have been stripped of their visas since section 501 of the Migration Act, the so-called character test, was changed last year.

Under the new laws, non-Australian citizens are stripped of their visas if they commit a crime carrying a sentence of 12 months or more. At the time it was touted by the tough-on-immigration Abbott government as a way to crack down on overseas bikies and serious criminals.

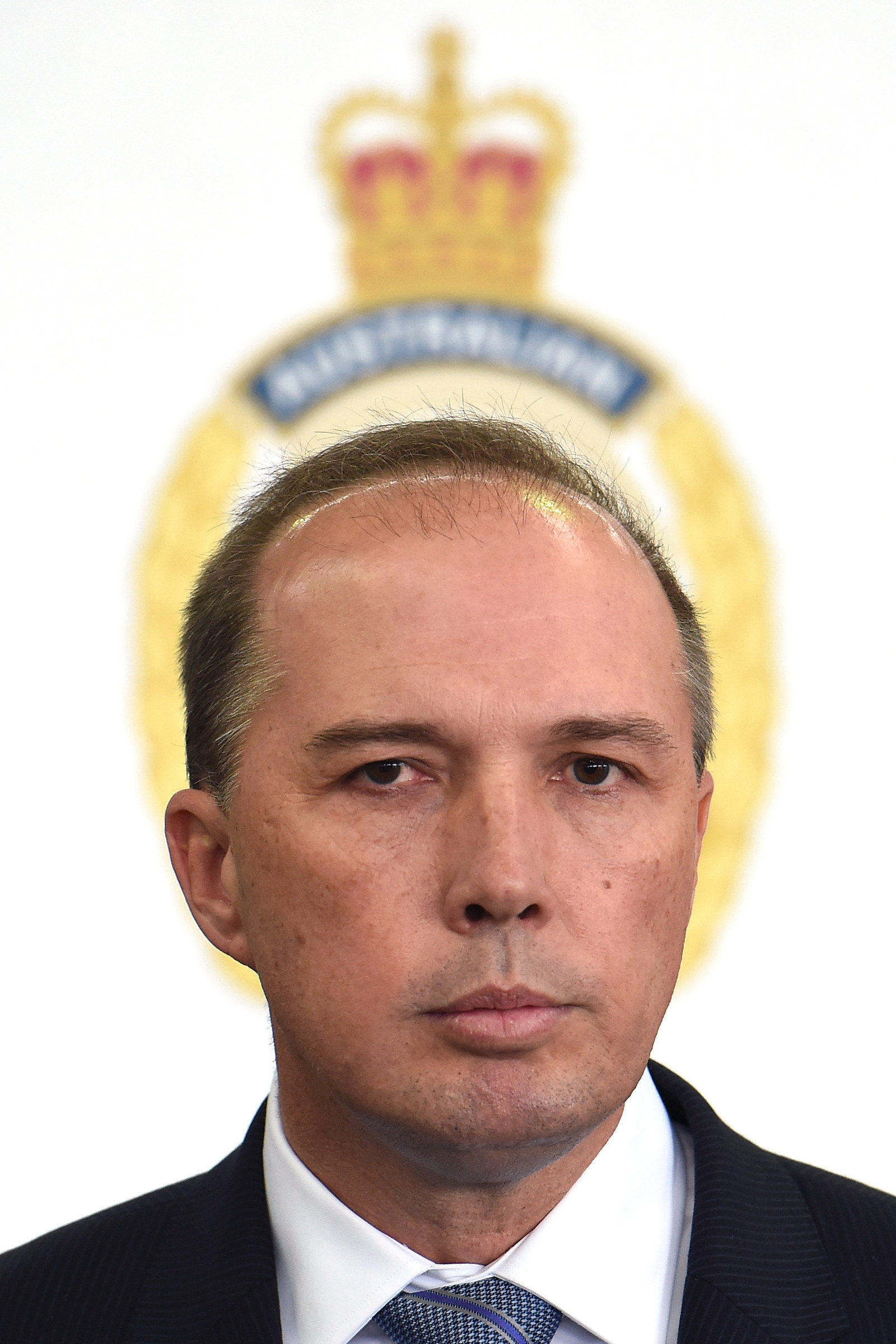

“It may be that they’ve been involved in trafficking of illicit drugs, it may be that they’ve been involved in gang rapes or it may be that they’ve been involved in sexual assaults of another nature,” said immigration minister Peter Dutton.

Under the old law, which had a higher threshold of a 24-month conviction, the immigration minister cancelled visas on a discretionary basis. Individuals’ circumstances, like their ties to Australia and family obligations were taken into consideration.

But now visa cancellations are automatic. Residents must apply to have the default decision revoked while they’re held in immigration detention. “501’ers”, as they call themselves, have no idea when their case file will even be opened by the immigration minister, let alone resolved.

How long they stay in detention before having the visa restored or being deported is not clear. Under questioning at senate estimates earlier this year, the Department of Immigration said the New Zealanders who have had their visas cancelled stay in detention for an average 127 days. The department could not provide BuzzFeed News with more recent figures for other nationalities.

It’s a slow, invisible process that detainees find infuriating, and near impossible to make sense of. Their detention feels particularly cruel given this indefinite detention is handed to them after they’ve finally served their jail sentences.

“It’s a big waste of time,” said Michelle. “It’s wasting our lives, making our families suffer for nothing. They don’t know what’s going on they have to sit and wait themselves.”

With the number of asylum seekers coming to Australia by boat slowing rapidly, the 501’ers kept in limbo are starting to become the very public face of the country’s hardline immigration policy. Last month, detainees at the Christmas Island detention centre rioted for three straight days, seeing guards flee for their safety, windows smashed, fires lit and at least one detainee armed himself with a chainsaw.

At the time BuzzFeed News spoke to detainees who said tempers had boiled over because of a recent detention centre death and the deeply frustrating process of 501 detention. They’d served their jail sentences, but they were still locked-up. After sending in riot police to take back the centre, 12 New Zealanders had their visas revoked and were sent back home. Peter Dutton described some of the men as “hardened criminals”.The same can not be said for Michelle.

Before being taken into detention Michelle was an active mother and grandmother. She still talks about her old life in the present tense.

“My daily life revolves around my daughters and grandchildren. Even though I own my business I include them in everything I do. Taking them to school every morning, picking them up, having them over for dinner, having them over every day”

Her detention and looming deportation have affected her mental health; it’s also affected her tight-knit family. Daughter Rhiannon said the stress of her mother’s situation led to her breaking up with her partner, and her children are struggling to cope.

“Mum’s always been around. My children have just completely shut down. They’re very… they have changed. When the kids aren’t with me they’re always with grandma. They’re missing all of that,” she said.

“I’m having trouble explaining to my kids what’s happening because I don't understand why she’s not here.”

The government makes the case that holding an Australian visa is a privilege and convicted criminals don’t deserve to stay in Australia.

“People who are involved in the trafficking of amphetamines or ice to kids, people who are involved in paedophilia, murder or serious crime otherwise cannot expect to stay in this country,” Immigration Minister Peter Dutton said in January.

While many would find little to fault in that premise, Michelle is baffled by the idea that she’d be considered in the same category as a paedophile or a murder. Her criminal history, which includes two terms of imprisonment, is long but made up mostly of fines for drug possession. She said she doesn’t drink or smoke cigarettes, but enjoys a joint.

“In the community she’s not seen as a substance abuser. She’s just a bubbly old lady who does what she does,” said Rhiannon.

“In the community she’s not seen as a substance abuser. She’s just a bubbly old lady who does what she does."

Detention centres around the country have been steadily filling up since the changes to the Migration Act were made, and more and more cases like Michelle’s are emerging: long-term residents with deep family ties to Australia, facing deportation for seemingly benign offences.

New Zealand media in particular has led the charge. With so many Kiwis in Australia and relatively few pathways to citizenship they are by far the biggest nationality affected by the laws. That intense media scrutiny has brought diplomatic pressure, including public interventions from Prime Minister John Key.

In October, as Prime Minister Turnbull and Foreign Minister Julie Bishop acknowledged New Zealand's concerns ahead of the PM’s first trip to across the Tasman, the Immigration Minister dug in.

“If people believe that somehow I'm going to backflip or bend in relation to these cases, they have got it completely wrong,” he told 2GB’s Ray Hadley. “We need to make sure that we keep our society safe, our borders secure. That's exactly what we're doing and I'm going to find more of these cases.”

Despite the minister’s hardline rhetoric, the government did in fact bend to the sustained diplomatic pressure. Facing estimates, Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection Mike Pezzullo promised to put Kiwis’ cases at the top off the pile.

“We will give priority to the New Zealand group...and then others will be dealt with as and when resources can be afforded to those caseloads,” said Mr Pezzullo.

But that assurance raises the prospect that those awaiting deportation to other countries, like Michelle, may have to wait even longer to resolve their cases, a point not lost on Labor Senator Kim Carr, who asked repeatedly if this would not create a precedent for other nationalities. In the same exchange, Senator Carr said politicians were increasingly being asked to intervene in such cases.

“Most people I talk to, members of parliament, are saying they are getting representations from people who have been in this country for a long time,” said Senator Carr.

“They are being faced with deportation. They will often have kids here. They have longstanding family relationships, but because of these changes in the law they are now being required to leave.”

One of those MPs is Michelle’s local member Bob Katter. He became aware of her case last month after Michelle turned to his office in desperation.

“There’s not the slightest shred of doubt that if you're born to an Australian mother you’re an Australian. [Michelle's] mother is Australian, she’s Australian,” said Mr Katter. “The woman’s been here for 52 years. If she’s not Australian who bloody is?”

Katter has been trying to schedule a meeting with minister Dutton to discuss Michelle’s case, but so far hasn’t been able to get an appointment.

“I don't think the minister is going to be prepared to talk to me on this case. It’s one thing for him to refuse to overrule the department. It’s another thing for him to be refused to be confronted one-on-one.”

“They [the department] are defending themselves against their outrageous behaviour and they don’t care if she rots in that prison or whatever it’s called forever. This is evil. Cases like this just scare me."

The Queensland MP is even more sceptical of the department providing Michelle a fair hearing.

“They [the department] are defending themselves against their outrageous behaviour and they don’t care if she rots in that prison or whatever it’s called forever,” says Katter. “This is evil. Cases like this just scare me.”

But just what does Australia owe its long term residents?

“What if the individual has lived in Australia from an early age? Do we not, as a society, then bear some responsibility for how they have turned out?", academic Peter Mares recently asked in online academic journal Inside Story.

It’s a question that’s particularly pertinent for Michelle given her history in state care.

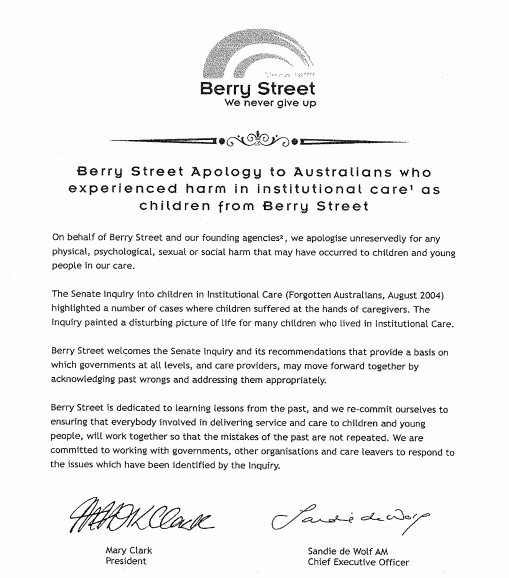

For much of the last century out-of-home care institutions were austere and abusive places endured by the 500,000 children, including Michelle, who walked through their doors. Isolated from family, kept away from loving adults in punitive homes they were stripped of their childhoods and exposed to abuse. In 2009 then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd formally apologised “for the tragedy, the absolute tragedy, of childhoods lost”; that “little ones who were entrusted to institutions and foster homes instead, were abused physically, humiliated cruelly, violated sexually”.

The place Michelle was kept for seven years, the Sutherland St home, was sadly typical. A few years before Mr Rudd’s apology, former residents received an official apology for “physical, psychological, sexual or social harm” caused by the home.

Michelle’s fate – substance abuse and incarceration – is common for those institutionalised as kids during this period. A Senate report into these “forgotten Australians” paints a sad picture:

“Very few children who experienced institutional care for long periods or at crucial stages of their development have escaped detrimental effects in later life and this has often damaged their ability to live as effective members of society. Their problems often include...high incidences of alcoholism and substance abuse”

Michelle said specific memories of her time there have been repressed. Despite repeated attempts with psychologists she can’t breakthrough or retrieve any memories. Rhiannon isn’t so sure.

“She doesn’t talk about that place much. I don’t know if she really doesn’t remember but I do hear her talk about some things...She just says it was a horrible place,” said Rhiannon.

In the 43 years since she left the Sutherland St home, Michelle has tried to unearth her memories of the place, to understand her childhood and how it may have affected her adult life.

Facing an indefinite stay at Villawood Detention Centre, she now has time on her side.

BuzzFeed News and The Project repeatedly sought answers from Immigration Minister Dutton's office in relation to Michelle's story, but despite many requests for comment we received none. However, we can confirm the minister's office is aware of Michelle's family situation, her long history in Australia and her indefinite detention.