It’s 10 a.m. on an October morning in Orange County, and people are already dripping sweat. The crowd, mostly made of teens and early twentysomethings, is lined up outside of Santa Ana’s Yost Theater, leaning on stanchions that slip down with every slouch. They’ve come from Southern California and a smattering of faraway states: Washington, Hawaii, Kentucky, Texas, Minnesota, and New Jersey, to name a few. It’s supposed to hit 100 degrees today, but these kids are wearing gloves. Inexpensive white cotton gloves, like the ones they sell in the Walmart checkout line.

They’re gathered for the fifth annual International Gloving Championships, the Super Bowl of an emerging sport most people have never heard of. Imagine breakdancing, with your hands, with Christmas lights stuck on your fingertips. Imagine a Day-Glo Edward Scissorhands boogying down at a Tiësto show. That’s gloving.

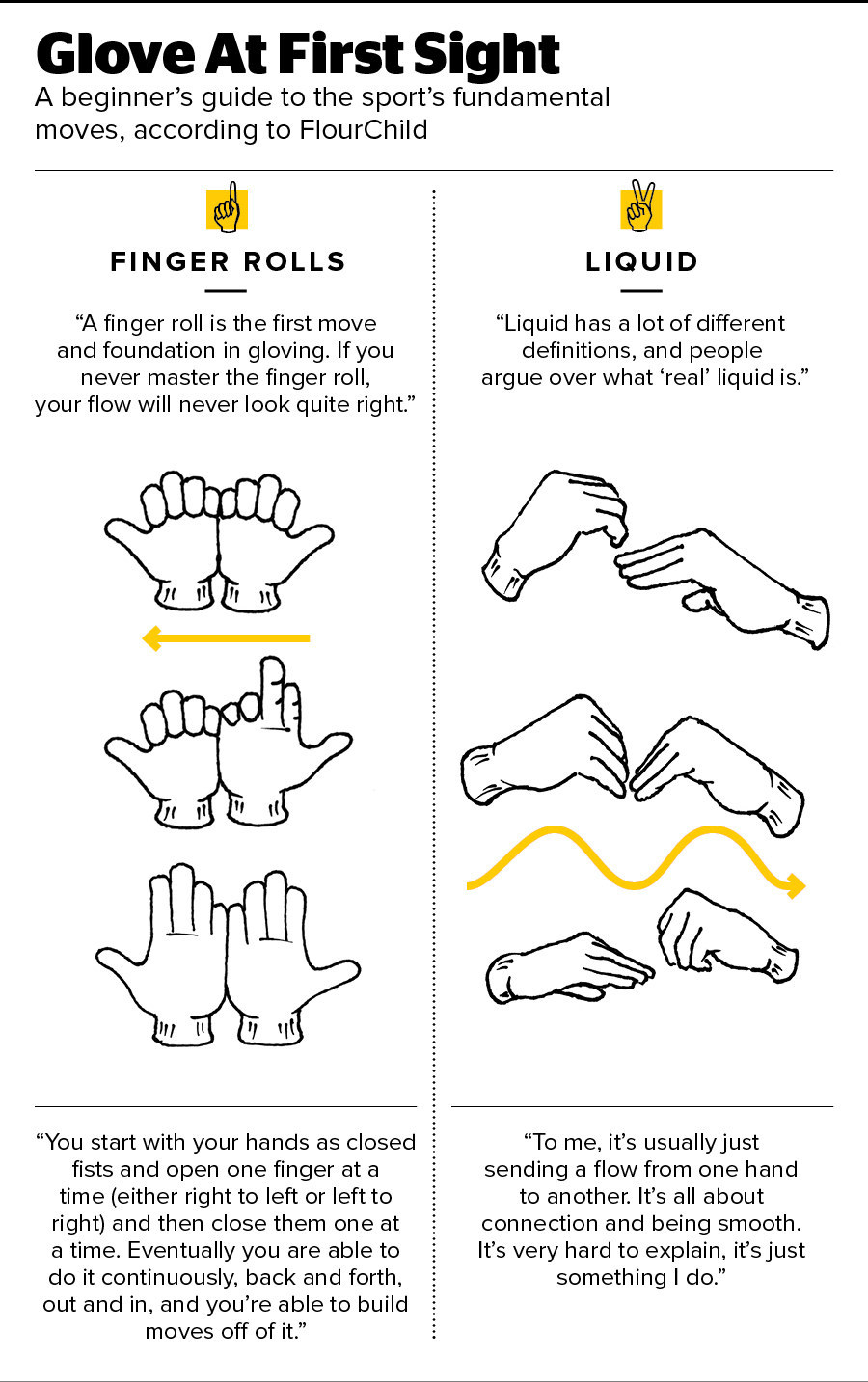

Gloving began as a dance at raves, but competitive gloving means going head-to-head: crowding into small blocked-off squares on a venue’s floor and freestyling along to a song, using the hands (read: lighted fingers) predominantly. Judges score the dance-off based on player’s execution, musicality, and presentation. Boosters are betting it’s the next subculture to go big: skateboarding meets e-sports.

In one line, for spectators, there’s Kennedy, aka Phantom, a 13-year-old boy who has never been to a gloving event before; his mom and sister drove over an hour from San Bernardino to get him here. Up the venue’s narrow stairway, the other line, for competitors, streams onto a balcony. DePaul University student Evan Dallas, aka Materia, is very, very nervous. “I feel like I’m gonna pee my pants,” he admits. “Indigestion is prominent.” Materia is here with his “second half of gloving,” Anna Hofmockel, gloving name FlourChild, a fellow Chicago native now attending culinary school in New York. They don’t think they’ll win today, but agree traveling the thousands of miles to be here is worth it.

Further back, Lunar, real name Raja, is wearing tiny denim shorts, knee-high fringe boots, and a crop top airbrushed with her gloving name. She wears her hair in mini–pigtail buns; unlike other glovers, she’s dressed more for Coachella than the skate park. She drove in from Phoenix with friends from the Arizona State University Gloving & Flow Arts Club, and today is her 20th birthday. That she’s one of few women present isn’t lost on her. “As a girl,” she says, when asked about her aims for the day, “it comes down to how many guys I can beat.” The Tutting Liquid Ninja Turtles, a crew of veteran glovers in their mid-twenties (which counts as “old-school” in the mostly under-25 crowd), are also present, devouring a pizza at 10 a.m.

Under a registration tent, there are the organizers, many of whom are also competing today. They work for EmazingLights, the company founded five years ago by Brian Lim, the now-28-year-old Angeleno who grew up watching his Chinese immigrant parents run a 24-hour doughnut shop. Emazing hosts IGC, and is also by far the biggest brand selling the gear needed to compete. In the words of the company’s president and COO Scott Elliott: “If we're Pepsi, there’s no Coke.”

Lim’s ambitious, and will proudly tell you that what started by selling lights out the trunk of his car has exploded into a projected $13 million in sales this year, six brick-and-mortar stores across the U.S. and Canada, a 30,000-square-foot headquarters down the street from Disneyland, and a staff of more than 50, many of whom are Lim’s friends from the scene. Along the way came ABC’s Shark Tank, a promised $650,000 deal with billionaire Mark Cuban and FUBU founder Daymond John, and, some rival light companies say, playing dirty to get ahead.

Today, 800 people are expected to attend the fifth annual IGC; around 140 will compete. They’ve come from the nearest suburbs and opposite coast. It’s a big ask on a college freshman’s budget, especially when many say their non-glover friends and family don’t understand the pastime. But, for the challengers, it’s worth it. They meet their online best friends IRL, compete for a $1,000 novelty check and the glory of being crowned champion, and, win or lose, hug it out after every round. This is their Comic Con and World Series and homecoming all in one.

What will it take to legitimize gloving as a sport and art form, with pro athletes and corporate sponsors and coverage on obscure ESPN networks; thriving even after EDM is no longer the reigning music trend? It’s a lofty goal, but Lim thinks today’s championships are a big step toward getting there. “With actual judges and scorecards, how can you not be legit?”

“Any more questions on the smell rule?”

Around noon, in the alley next to the venue, Corey Defeo, aka Ice Kream Teddy, is doling out instructions to the judges. Teddy is IGC’s red-haired reigning champ; he's been gloving for seven years and coordinating competitions for three. The judges, who — in addition to their role as tournament officials — can also compete, are dressed in red and blue T-shirts screen-printed with Emazing’s mascot in a referee jersey. Some guzzle water bottles, some vape, and others pick through an arrangement of perfectly curated stoner snacks: Ruffles Sour Cream & Onion chips; traditional and Choco Chips Ahoy; two flavors of Pringles; cans of Monster energy drink (IGC’s biggest corporate sponsor); Little Debbie Oatmeal Pies; a box from a restaurant called Wings filled with, presumably, wings.

The smell rule Teddy references (quite literally, if someone reeks, the judge has the right to politely eject them) speaks to the nature of the game: kinetic young people in close quarters. “I have been that fucking person, and it feels like shit,” Teddy continues. “So, yes, it’s something that you want to be reminded of when you are that person but not to the point of, like, embarrassment.”

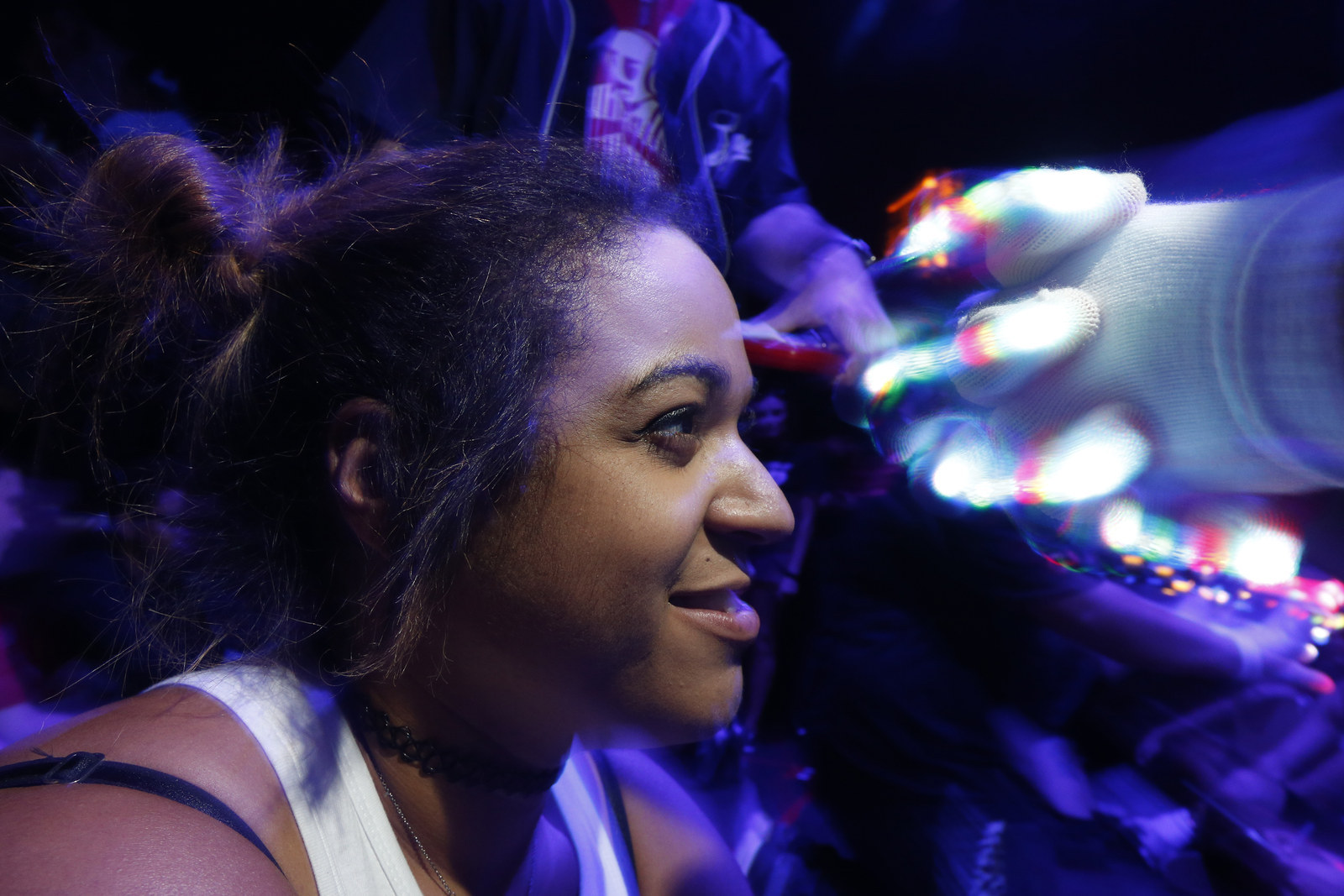

The competition is styled after dance-offs or rap battles, and takes place on a venue’s floor instead of on the stage, dozens of battles happening at once. In the dark theater, individuals are paired up and face each other, crouching down, just inches apart — like a chicken fight minus another person’s shoulders. The DJ plays 90 seconds of music (usually EDM, though everyone insists that, technically, you could glove to anything: country, rap, metal), during which one of the glovers does a light show right in his competitor’s eyeline, dancing along to the song’s melodies, beat drops, and mood. Though the competitors practice their moves beforehand, it’s all freestyle: They don’t know what song will be played prior to the round. Once the song ends, the other competitor freestyles to another 90-second song. During the performances, at least one judge takes notes and decides on a score for each. The glover with the highest score takes the round.

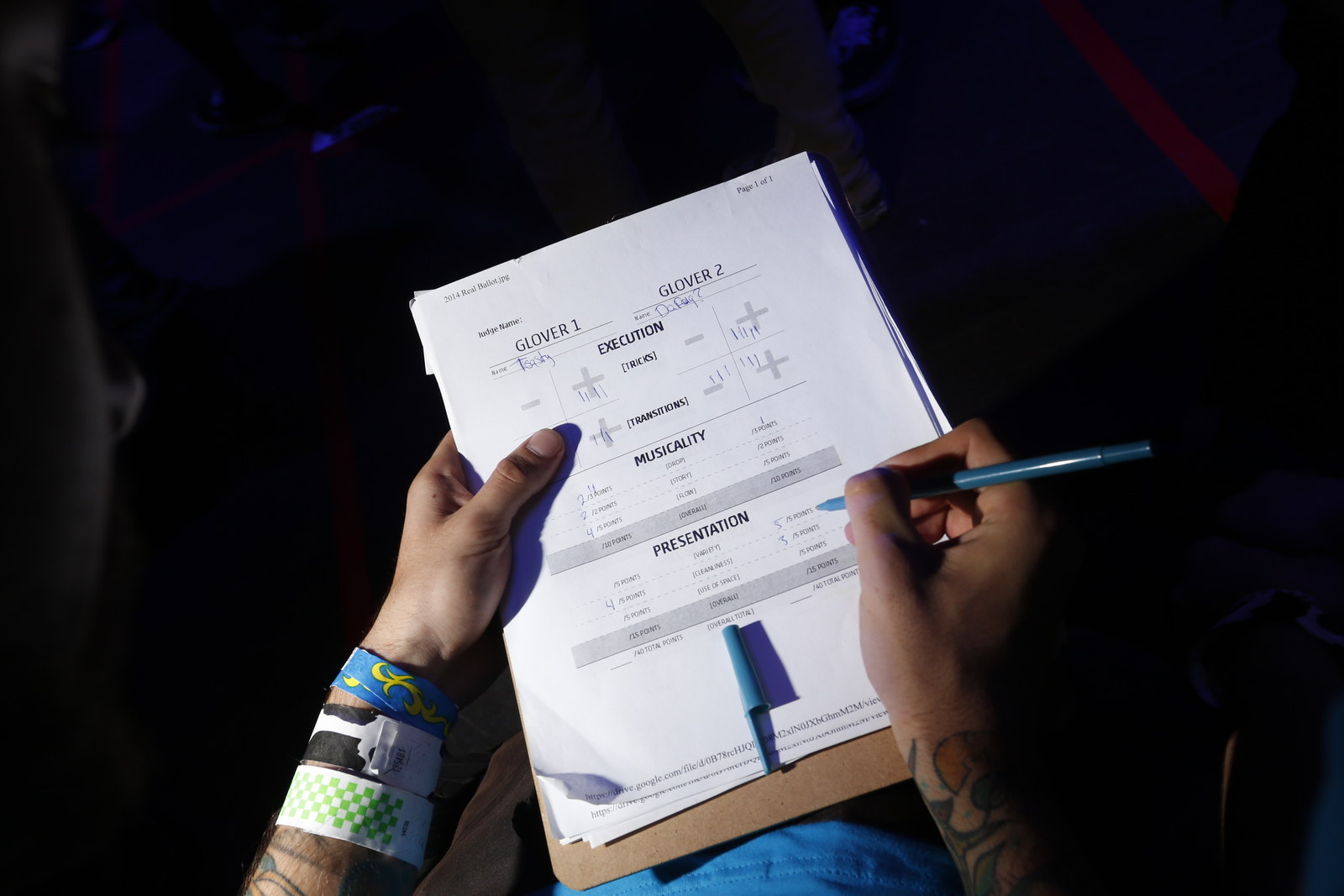

What makes someone a winner? The scorecards are broken up into three categories: musicality, presentation, and execution, which is divided into tricks and transition. When individual competitors and judges are asked to define good gloving, though, the answers vary. Some people favor hand tricks like tutting and finger rolls, while others prefer to incorporate full-body movement, like pop-and-lock techniques.

Others, like Lunar, say the narrative you create with your movement is most important. “Every show I give is a different story for a different person,” she explains. “It goes off vibe; it goes off who you are as a person.” That’s why performing at eye level is key; like virtual reality glasses, it transports your opponent-as-audience to another world. What’s set in stone is what not to do: Glovers lose points for mistakes like repeating moves within a performance or accidentally smacking their opponent in the face.

The competitor registration line leads to a card table where girls in IGC T-shirts sit with clipboards, checking in those who preregistered and finding space for those who haven’t. Under a constellation of disco balls and strobe lights, the hosts ask to see everyone’s ID, but many are so young they don’t have one. Twenty-one-year-old Alex “Cypher” Balladares, an Emazing employee and IGC competitor, calls downstairs on his earpiece to figure out a solution.

Meanwhile, others do finger tricks with their IDs or give informal light shows to their neighbors in line. One fiddles with a GoPro camera, and several others commandeer an empty table to put new batteries into their lights. Light sets range from $20 to $180, depending on how custom they are. The lights themselves are small but versatile, about the size and shape of a bloated penny, and can be programmed to change color when they move. Once registered, each participant is given a name tag, which everyone agrees is quite uncool, but the glovers abide.

The day is broken up into two tournaments. The 16-person Legends bracket, which closes out the event, is the tournament of champions. The Legends include the winners of this year’s local tournaments (called BOSSes, short for "Battle Of Supreme Swag"), the previous IGC champions, and a handful of fan favorites voted in via Emazing’s website. They are joined by the two winners of that day’s open bracket tournament, which is how IGC begins.

“The open bracket tournament is more or less the last chance qualifier to join [the Legends] bracket,” Teddy explains. Today, 128 competitors will enter the open bracket. They include IGC regulars who’ve never won before, people from out of state making their IGC debut, and total rookies just getting into the scene.

Outside, Teddy is still going through the rules with the judges, but they are starting to get antsy, catching up with friends and asking for clarification on scoring. “General etiquette rule, guys, hey, general etiquette rule…” Amid the murmuring, Teddy is getting frustrated and erupts: “GUYS, UNTIL I SAY, 'THANK YOU, I’M DONE,' I NEED YOU ALL TO BE 100% QUIET.” The crowd continues to talk.

Two days earlier, in a small conference room at Emazing’s Anaheim headquarters, Teddy explains how he went from gloving for fun to working part-time on Emazing’s customer service team to his job today, as the company’s wholesale and competitions coordinator. He is passionate to the point of boisterousness, often talking over co-workers to get out a point. He describes everything using his version of motivational startup speak, fitting for a salesman born of two salesperson parents.

“When you walk in here, you know everybody doesn’t just want to be here; they feel the need to be here. If anybody isn’t giving 110%, you look at them like, You good? You need a nap, buddy?”

Teddy won IGC last year, and feels good about his chances for a repeat. His confidence wavers only when asked what seems to be an obvious question: Why should he, the “competitions coordinator” for the company that’s putting on the event, get to compete? Does anyone ever complain that it’s unfair?

“Umm…”

For the first time, Teddy is the one who’s cut off. “Yes,” says Cypher affirmatively. Everyone laughs.

“Yeah, I got a lot of pushback,“ Teddy admits. “Honestly, working here does give me an advantage. And it’s the same advantage for anybody else that works here: The fact is, I’m around gloving all the time.” But aside from that, he insists, it’s just his hard work paying off.

“After IGC 2012, up until then there had been a rule that if you won BOSS, you could not compete until the next IGC. The idea is to create multiple champions and create multiple stars,” Teddy explains. “I disagreed with that. I firmly believe that if you are the best, you should get to compete until you are dethroned, until someone actually is better than you. And I fought Brian [Lim, Emazing's founder] very, very hard on that statement. And I said, ‘If you don’t change the rule, I’m just going to keep getting second every single time until you change it.’” According to Teddy, he did — Lim bent, and soon thereafter appointed Teddy to his competition-coordinating role. And that’s how Teddy became both the person in charge of explaining the rules to the judges and the day’s possible winner.

“ONE HUNDRED PERCENT UNTIL I SAY, 'THANK YOU, I’M DONE,' LIKE NOT A WORD, SO I CAN GET THROUGH.” The crowd quiets. “Thank you. OK, remember that there are people here — some of them are in this very group, who have flown out here or have driven an obscene amount of hours to be here. So keep in mind that when you have this shirt on you are a representation of why they flew out and why they drove out here: because they love the same thing you do so goddamn much.” He wraps up: “Thank you so much, have fun, because really, this is about to be a great event. Bring your A game because I’m sure as fuck gonna need it.”

After a morning of harried preparation and patient waiting, everyone piles onto the floor of the theater, which was built to host vaudeville shows in 1913. It’s dark, but you can make out rich red velvet curtains draping over the walls, at odds with the purple and blue club lights shining from the rafters and the massive DJ booth dominating the stage. What’s most noticeable is the neon tape on the floor, marking off squares each dueling duo will use to compete.

Gloving wasn’t always competitive. Brian Lim started doing it recreationally, attending raves with his now-fiancé as a senior at UCLA in 2010. But when EDM festivals started banning gloving soon thereafter, citing fire hazards and concerns about drug use, Lim got to work. “One way to prove gloving was legitimate was to make it a sport,” he says. Lim and his team created the leagues, the format, the rules, the scorecard. He hired someone to set up teams at colleges, to spawn a new generation of competitive glovers (who, not coincidentally, could become Emazing customers). He started weekly “Friday Night Lights” jam sessions and regional BOSS tournaments at his stores, plus today's winner-take-all annual one, and called it the International Gloving Championships, even when kids from Orange County were the ones competing.

Before the competition can begin, Lim gives his State of Gloving address. He’s slight but fit in his gray-on-gray T-shirt and blazer, speaking with rehearsed authority as he presents along with a slideshow projected above him. “By our estimations, there are over 200,000 glovers in the world today,” he declares, crowd cheering. “And that equals over 4.7 million light shows thrown. Yup, we did do the math on that one.” He doesn’t talk about his bottom line, but the subtext is clear: The more gloving grows, so does the Emazing Group (which, in addition to EmazingLights, includes e-commerce apparel shops iHeartRaves and Into the AM and charitable initiative Glove4Glove, which donates glove sets to nonprofits like Rock the Autism).

“Now, where are all these glovers talking?” Lim continues. “It’s the infamous Glover’s Lounge. Last year, we had 8,000 members. Today, we have over 17,000 and [are] continuously growing every single day.” Glover’s Lounge is the private Facebook group that, true to Lim’s word, is the hub for all things gloving. Members post videos of themselves gloving to solicit feedback, share gloving memes, and ask for personal, gloving-related advice (“Does anybody treat gloving as an act of courtship? Like couples who glove, is it as romantic for y'all as it is for me & mine?”). As of writing, the group has more than 18,000 members.

It’s also become the hub for gloving drama, especially as the scene grows and, along with it, tensions between members new and old.

First of all, the drugs. Short answer: Yes, people use them. It’s not hard to imagine why the blinking trails that gloves produce would be catnip for the tripping, and many old-school glovers insist that getting high is at the heart of this art form. All the new stuff — the competitions, the leagues, the college teams — miss the point.

But then you have the new generation, the kids who could launch Lim’s business from a rave subculture to a national pastime. Kids — like 13-year-old Kennedy — who found gloving on Vine or YouTube and became obsessed with it in their childhood bedrooms, far away from the rave scene. Or the engineering students who got hooked on the University of California, Berkeley, campus, where they earned college credit for taking a class on gloving. These are the folks Lim needs in order to maintain steady growth, especially now that the once-unstoppable EDM festival market that brought raves to the mainstream has begun to slow considerably.

Talking in a greenroom backstage, Lim says the association with drugs can be a hurdle for the brand, both with festivals that've banned gloving and companies it might one day want to partner with. “We’ve been trying to build up our portfolio to showcase the evolution of gloving over the past five years — that it’s not just a rave thing where people are waving their hands around, it’s talent. You can’t show up at a competition like this, with hundreds of other glovers, and be drugged out. It’s just ridiculous.” But proving that won’t be cheap: Lim says Emazing will spend at least $50,000 putting on IGC, money it won’t make back selling tickets for $10 a pop. But, he says, if an event like this can bring the community together and show it’s respectable, it’s worth it.

Let Lim make one thing clear, though: He’s not anti-drug, nor does he think it should fall on him to regulate drug use at his events. “It’s like music. Is music great by itself? Is music great when you’re on substances? Like anything, drugs are popular for a reason. I don’t think gloving is going to solve that problem.” Gloving is for you if you’re a raver, a student looking for a Hacky Sack alternative, or a parent hunting for a Christmas gift that minimizes screen time. Gloving is for you, whoever you are.

On that point, he’s pretty convincing. Besides one overserved, angry dude who is ejected from the venue, IGC is a safe, welcoming event. Its crowd is mostly young and male, but it's racially and geographically diverse. And it’s diverse in another way. “It doesn’t matter if you’re straight edge or not; you’re still welcome. It’s whatever your preferences are. We just try to make you feel comfortable,” Lunar says. It’s all very PLUR: the rave mantra meaning Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect.

What’s not so PLUR? According to Emazing’s rivals, the way it does business. Raymond Stone is the founder of Rave Ready, which sells a wide range of rave clothes and accessories, including gloves and glove lights. His company sponsors a gloving team, and one of its members, 16-year-old Pilgrim from New Jersey, is in the Legends bracket today. But when Stone shows up at IGC with a camera crew to take photos for his blog, he hits a snag: Emazing’s PR rep explains that Stone needed a preapproved press pass to enter with a DSLR camera; Stone counters that an Emazing employee said it was fine for him to come days before, and it seems rather fishy that he’s being turned away now.

“Brian is very strong on branding,” Stone says, looking glum, camera dangling from his hand. “He doesn’t want any other company to be able to promote anything successfully. It’s progressively gotten worse.”

“I don’t think you should fight your competitors,” Stone elaborated over the phone. “Of course you’re always going to be fighting with your competitors for sales, but I started a rave store because I was a raver and I believe in PLUR and kind of everything that is involved with the rave scene. And he kind of doesn’t.”

Unfortunately, capitalism isn’t PLUR. Lim’s a savvy businessperson, but he also loves gloving and the community around it; participants describe him as a big brother of sorts. “All they want is to promote positivity, and it’s working,” Materia says. “If you work hard at something that you love, you’re gonna be just like him,” another glover, a 16-year-old known as Lil Homie, from Miami, adds. “You’re gonna excel.”

In an interview with L.A. Weekly earlier this year, multiple individuals suggested Lim either stole their product ideas or otherwise sabotaged their efforts. Lim denies this; in fact, he’s currently engaged in a legal battle arguing just the opposite. In September, EmazingLights sued Ramiro Montes de Oca and his Quantum Hex for patent infringement, misappropriation of trade secrets, breach of contract, and other similar complaints. “Ramiro is unfortunately an ex-employee that stole from us, our intellectual property, and started his own company,” Lim says. Montes de Oca disagrees, arguing that he was never an Emazing employee, but a contractor, and accusing Lim of forgery (Lim refuted the allegations). The drama dominated Glover’s Lounge for weeks.

In the greenroom, Lim expresses regret for ever “getting off on the wrong foot” with other brands, but largely shakes off the criticisms. “I think if you don’t have any haters in this world,” he says, “you’re not doing something right.”

Back in the theater, the open bracket has begun. Corporate politics couldn’t be further from the competitors’ minds as they crowd around monitors set up in the front and back of the room, waiting for their first-round scores to go up. Some deconstruct their performances with new friends or play with their hands while they wait; others stare at the screens, the only things glowing besides fingertips and cell phones in the dark auditorium. It is now 2 p.m., and the room has been fed a steady drip of EDM since 11.

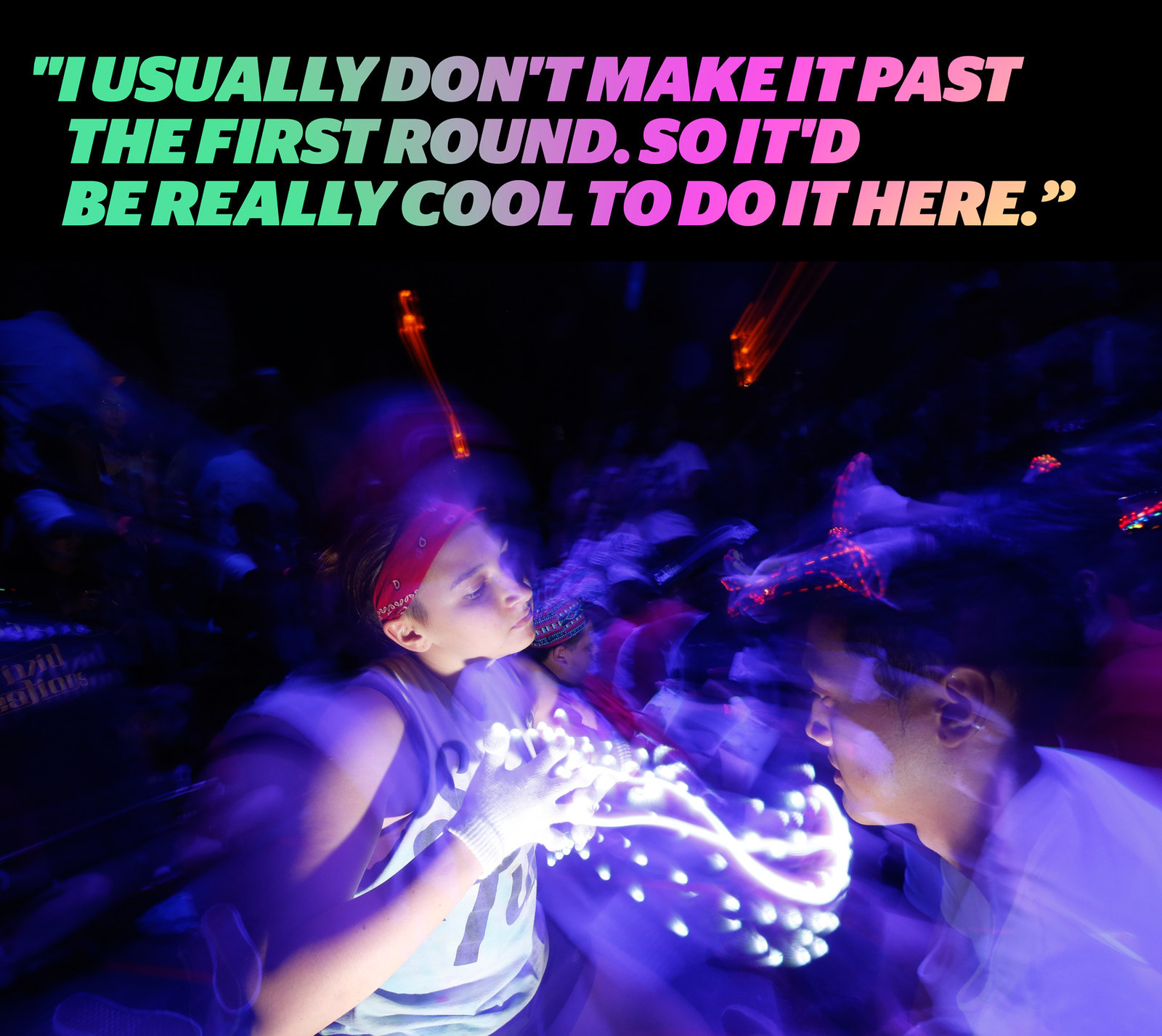

“I think some of my friends, after the first round, felt a little discouraged,” explains New York glover FlourChild. “Because some people think they take the round and then they don’t.” She says this year’s setup is better than last, when the open bracket was single-elimination: If you lost any battle, you were out. But today, she’ll get to go up against three different glovers, earning three points for every victory that will contribute to an overall score. The top eight overall scorers will move on to the semifinals. For FlourChild, getting to that round would be affirming. “That would mean a lot to me, because when I do little competitions in Chicago or New York, I usually don’t make it past the first round. So it’d be really cool to do it here.”

Materia and Lunar both won their first battles of the day, and are slated to go head-to-head in their second. They’re selected as “featured” glovers, called up to perform on the edge of the stage, where it’s recorded for Emazing’s social channels. The emcee counts down five, four, three, two, one, and Materia’s on, launching into his performance as a female voice chants over a mellow trance beat. “These voices are taking over me.” Materia starts off by leaning on his side, fingers creeping over his thigh like a spider until he springs up onto his knees. His right digits bounce over his left like a kid learning chopsticks on the piano. He’s most compelling when he’s working with his whole body, or switching his tempo from fast to slow to fast, like a screensaver: familiar but hypnotizing.

“Twenty seconds! Twenty seconds!” the emcee shouts. Materia finishes, grinning widely, and they hug. It’s Lunar’s turn now, and it’s as if she’s casting a spell over a crystal ball. Her fingers seem more flexible than his; her flow is undeniable. She’s been going to raves for seven years and seems like she’d be as adept with a Hula-Hoop as a glove set. She alternates between the organic movements of a moray eel and tight, meticulous tutting.

“Competing, for me, it’s pretty easy,” Lunar says after they wrap. “The second round was really cool because it was Materia. That was exciting. I’m pretty sure he beat me. I don’t care, but I get to do another round. My goal for today is to end up in the top 32. I don’t care after that — as long as I can get there I’m OK.”

On the other side of the theater, Materia weaves through the crowd to join FlourChild and the rest of their friends at the monitors. He looks like Jack Antonoff and comes across as similar parts sweet and neurotic. The scores are live. “I won?” Materia squeaks. “Holy shit! Did we all win?” FlourChild did not, but she insists she isn’t bothered and joins their friends for a group hug.

“My competitor put in a lot of technical work and after that came up I was like, ‘That’s it for me,’” Materia says with a self-deprecating sigh. “I was up against a chick named Lunar. She was really fun. Apparently it was her birthday today? I got two wins. That’s all I need.”

But Materia wins again. In fact, Materia starts to win every round. After the first three matches, Lunar is out. FlourChild is out. But Materia moves on to the top eight. Then top four. Then the finals, competing for one of the spots in the Legends bracket. And it’s clear why. Competing against his final challenger in the open bracket, Materia moves his hands in time with the heavy EDM thudding from the DJ booth on stage, his septum ring bobbing with every motion. He’s standing across from another young man, Krusty, who kneels to take in the view from eye level. Strobing lights emanate from each of Materia’s fingertips, trailing his movements as he pops and locks and waves his digits, which look like disembodied Mickey Mouse hands in the dark of the auditorium. He’s flexible, moving his whole upper body when he performs. He has rhythm, he’s theatrical, and he’s passionate. Later, he reveals gloving isn’t his first competitive art form; before this was Greek folk dancing, which he did for his entire childhood. He’s nervous and ecstatic with each successive win.

“This. Is. Unreal!” After the final performances of the open bracket tournament, the top eight are called onstage, and Materia sincerely looks like he is going to vomit. But his fellow competitors can’t stop complimenting him; his earlier challenger, Puppet, who’s here from Hawaii, even christens him with his lei.

The results are announced, and Materia doesn’t win. He doesn’t move on to the Tournament of Legends; he doesn’t get an opportunity to go for $1,000. But for the rest of the night, strangers come up to him and compliment his shows. They hug him and high-five him and recognize him for his skill.

Watching this, it’s easy to imagine how gloving could break big. Even if it’s not your art, after a day with the glovers it’s hard to deny that there’s skill here, that they develop form, rhythm, talent. The excitement is authentic, and the camaraderie, too. America has fallen in love with equally quirky hobbies before: Rubik's Cubes, Rollerblades, Astrojax. The hurdle will be hooking potential glovers who’ve never heard of it.

For Lim and his team, one way to sustain kids’ involvement was creating a sponsorship program. Glove light companies sponsor individual glovers, mostly rising stars who demonstrate talent at events or online. For Emazing's 29 sponsored glovers, the affiliation means receiving free merch, like light sets and batteries, and being invited to record videos in Emazing's studio. The company promotes the glover on its social media channels, and makes sure they have the tools necessary to build up their own. The goal is to turn glovers into celebrities in their own right. “You may not watch soccer, but you know David Beckham,” Emazing’s growth manager, 24-year-old Sam Berney, says.

Emazing Group COO Scott Elliott provides a more realistic role model: pro gamers and skateboarders. “We would love for them to be able to become professional glovers the same way you can become a professional skateboarder, a professional snowboarder, a professional video game player,” he explains. “To be in the position to say, ‘I make 200 grand a year as a professional glover and I fly all over the world to competitions,’ and have their parents just look at them in total disbelief — like I think a lot of video game players probably get right now.” The goal isn’t making light-up gloves the hottest toy of the year, but creating incentives for glovers to keep at it. “We don’t want to lose the coolness of it; we want it to organically move into popular culture.”

The Legends Tournament, glovers insist in the weeks leading up to IGC, is the big show, home of the most compelling, important duels of the whole year.

Unfortunately, they occur at 6 p.m. on a day that kicked off at 10 a.m. People are wiped out, crumpled in café chairs, vaping in front of the venue. If they lost in the first part of the open tournament, like Lunar and FlourChild, they’ve already been spectating for hours, trading lights and getting to know other glovers (easy) while not going stir-crazy (hard). The crowd has thinned noticeably. The DJ continually misses his cues; what was a laughable inconvenience earlier in the day is now soliciting real boos from the audience, even from some mild-mannered parents nesting on benches lining the venue, watching their children like hawks.

The crowd revives when the Legends Tournament gets underway. Consisting of only 16 competitors, Legends breezes by at a lightning pace. Teddy competes in a black T-shirt and black sport sunglasses, going up in the grand finale against an unsponsored, 18-year-old Texan who goes by the name Machine.

Teddy wins. After a celebration onstage in which hot girls in ravewear hand Teddy a giant novelty check, there’s an open-gloving session on the venue floor. But just as many choose to scurry outside, where they float in that euphoric bubble that trails an amazing show, everyone doing play-by-plays and spreading rumors about epic afterparty plans.

The first-ever two-time IGC champ makes an announcement: “I’m done competing,” he says. “At this point, there’s no point for me to keep competing. I could, and I like to compete, but with everything that I’ve done — quick backstory...” He repeats the story of getting Lim to change the rules, so he could win multiple tournaments a year. “But now, at the level I’ve attained with everything, I mean, multiple IGCs, BOSSes...” Someone calls him over for a group picture. What’s next? “Learntoglove.com. More to come later.”

In the days following IGC, the Glover’s Lounge again becomes a hotbed for controversy — namely, that the IGC was rigged, that Teddy shouldn’t have won, that it’s all a big conspiracy. If they took hold, those criticisms could be devastating for Emazing’s reputation, but the majority of Loungers talk the others down. It’s like Teddy says, IGC is not rigged: He just plays to the scorecard, which he helped write.

Twenty feet away, Materia and his friends sink into café chairs. “We could fall asleep on the table,” he says, laughing. “We’re trying to make tonight last as long as possible because we leave tomorrow.”

“When people were coming up left and right congratulating me, I was so overwhelmed that I literally ran out of the room,” Materia says. But sitting across the tiny metal table from his friends, the day’s sweat drying down and their eyes adjusting to natural light, there is a heady excitement of a second wind waiting to blow in. Once Materia returns to the small Chicago circuit and FlourChild is back at culinary school in New York, they will remember this contest — the excitement, the heartbreak, the beat drops and light flashes. “It’s that milestone,” he says. “It makes all this, playing with your fingers, worth it.”