The Case for a Tech Bubble

While many Silicon Valley insiders are dismissing the idea of a bubble, there are a number of worrying signs that history is being allowed to repeat itself and we are seeing a repeat of 2000.

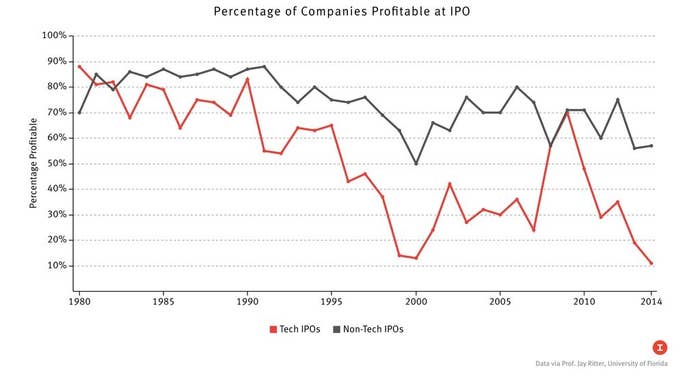

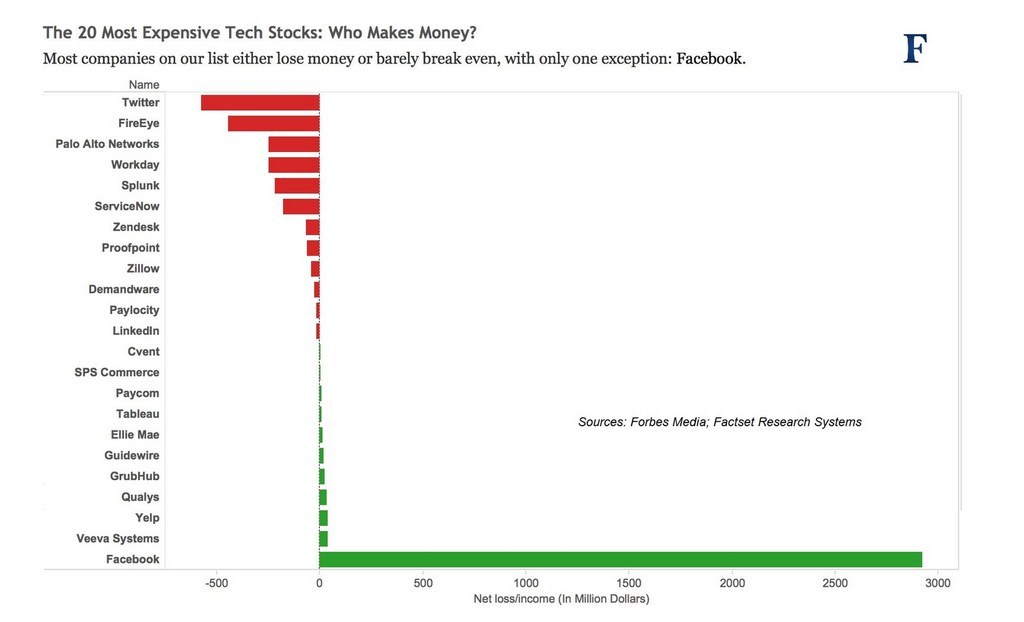

1. Everyone is going public. No one is making money.

The number of tech companies filing for IPOs is at its highest level since 2000 while the percentage of them that are profitable is at its lowest point in history. Of the 127 tech companies that filed for IPOs in 2014, only 14 were profitable. That means just 11% of those companies were making any money whatsoever (an even lower percentage than during the Dotcom Bubble).

2. Valuations are hitting the stratosphere

Recent analysis done by Tech Crunch found that there are currently 84 tech companies that are so called "unicorns" - companies that are valued to be worth at least $1billion. That represented a shocking 110% increase in the number of "unicorns" from a year and a half before. Several of these companies are less than three years old. The two charts below show the dramatic increase in tech company valuations between January 2014 and July 2015.

Just as in 1999/2000, tech companies are doubling or tripling in value over night. Spotify has gone from being valued at $1 billion in 2012 to $4 billion in 2014 to $8.5 billion in July, 2015. Uber's valuation ($41 billion) is greater than the value of the entire global taxi market that it is trying to replace. The sky rocketing of valuations on a large scale is a classic indicator of an asset bubble.

3. More money is flooding into the tech market than ever before

As the rest of the economy has continued to stagnate or grow at a very slow pace, more and more investors have been turning to tech companies in search of the possible huge returns. New investments in venture capital firms this year totaled close to $30 billion, almost double the $17 billion invested the year before. And investments by venture capital firms in startups rose from $30.1 billion in 2013 to $49.3 billion in 2014.

This influx of new money has flowed into the tech market because companies like Uber have seen their valuations rise by as much as 119% in just six months. Returns like that in such a short space of time are unfathomable in other areas of the economy. Overall, last year shares of publicly traded technology companies were up nearly 13.5% compared with 7.7% return of the broader S&P 500 index.

All in all venture capital companies currently have $156 billion under management, an even larger sum than the $146 billion they had under management in 1999.

The picture becomes very worrying when you understand the increasing level of risk that is being taken by an ever growing number of investors. Simply put - more and more people are pouring money into the tech market at the same time that an increasing number of those companies are losing more money than ever before. The huge increase in the valuations of many new tech companies is not being driven by rising profits and "true growth" but in fact just by new investor money. It is literally just the "bigger fool theory" taking place on a massive scale.

4. The money is coming from non-traditional sources

This is not what mutual funds are supposed to be doing. Mutual funds are seen as safe havens for money. They are supposed to be making low-risk, blue chip investments that people can rely on for regular, if not high, returns. Their primary advantages are the diversified risk and high liquidity they can offer investors. This is why pension funds and everyday Americans prefer to invest retirement savings in mutual funds and not in venture capital firms.

And the last time that mutual funds acted like venture capital firms? 1999. During the dot-com bubble, mutual funds like the Merrill Lynch Internet Strategies fund made its debut with $1.1 billion dollars in tech related assets. Over the following year it lost over 70% of its value and was closed down.

5. Burn rates are at their highest rate since 1999

A damaging aspect of this rise in easy capital is that (just as in 1999) it has created an environment in which new companies are burning through money at a rate not seen since the dot-com bubble. Several heads of major venture capital firms have complained that they have multiple companies in their portfolios that are burning through several million dollars a month. Because capital is so easy to get the incentive to run an efficient and lean start-up has been diminished. Start-ups are hiring more people than they need, paying them higher salaries than they should and renting offices that are larger and more expensive than necessary.

There are three clear indicators of this: 1) the migration of professionals from other industries into tech, 2) the sky rocketing of real estate prices in Silicon Valley, and 3) huge growth in advertising spending

1. As Bloomberg recently noted, many finance professionals and bankers are now leaving their jobs in finance to pursue jobs in the tech industry. This is happening in part because many brand new, unprofitable start-ups are able to offer very high salaries, competitive with those offered by huge, established financial firms that have existed and been profitable for over a century. These bankers are drawn to the easy riches and more comfortable lifestyle that working for a start-up can offer.

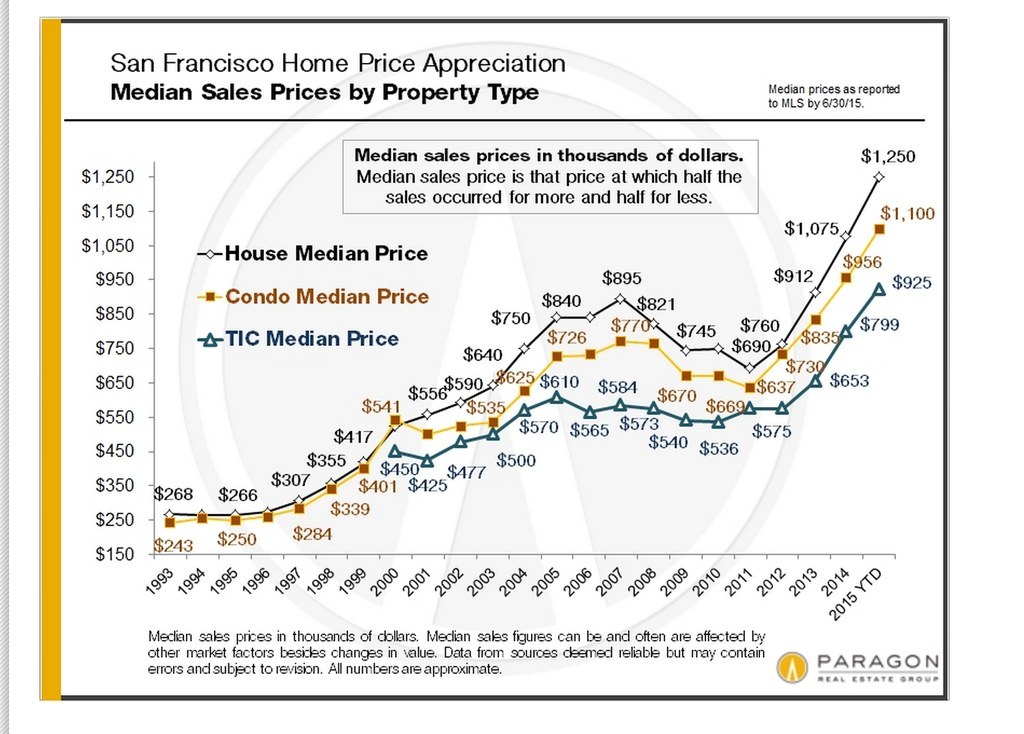

2. Real estate prices in the San Francisco / Silicon Valley have exploded in the past four years. Four years ago in 2011, the median sale price for a house in San Francisco was $690,000. Since then it has almost doubled. The median sale price for a house in San Francisco today is now $1,250,000.

You might wonder how that compares with the market during the dot-com bubble? Between 1995 and 2000 median housing prices in San Francisco also doubled - from $266,000 to $541,000.

The cost of leasing office space has also risen sharply. Since 2010, office rents have increased by almost 90% and are now at the same levels they were in 2000. According to Bill Gurley, a partner at the venture capital firm Benchmark, the demand for office space is so high that landlords are requiring many start-ups to sign leases for periods of ten years. According to him, the last time this occurred was in 1999.

3. Start-ups aren't just burning money on salaries and offices. They also are spending huge amounts of money trying to gain market share from their competitors. Facebook Mobile Ad sales have sky rocketed in the past few years as mobile app start ups pour more and more money into reaching potential new users through ads on the social media app. During the fourth quarter of 2014 alone, Facebook generated $2.5 billion in mobile ad sales (69% of its total ad revenue) - a 53 percent year over year increase.

This rise in ad sales is being driven by the huge demand represented by start-up companies desperate to increase their user base. These start-ups can only afford to buy these ads because it is so easy for them to raise money from investors in the current market. It has become something of a vicious cycle as start-ups compete to outspend each other, driving up ad prices higher, which in turn requires them to raise more money from investors on the basis of potential future earnings that will only materialize if they are able to draw enough users from their competition. This artificially inflated demand saw Facebook's average price per ad rise 285% last year even as the number of ad views plunged 62%. One start-up, Adore Me, cost-per-click on Facebook surged 180% year-over-year during its first quarter.

Start-up companies have also been taking out an increasing number of physical and print ads. The proliferation of start-up related ads has been so noticeable that there are now even internet blogs that post daily updates of new ads spotted around New York City.

Just as during the dot-com bubble, brand new start-up companies are even purchasing ad time during the Super Bowl at an astronomical cost. In many ways this explosion in ad spending to achieve rapid growth is identical to the "Get Large - or Get Lost" mantra of the dot-com boom in which the number one focus for most internet companies was to expand its customer base as quickly as possible at whatever cost necessary.

5. The anecdotal evidence is there for anyone to see

Here are a few stories that will probably surprise you and show you that Silicon Valley has turned into a parody of itself.

The Story of Secret

In January, 2014, David Byttow and Chrys Bader founded a company called Secret - a anonymous-sharing smartphone app in the same vein as Yik Yak or Whisper. By March, 2014, they had raised $8.6 million from venture capital firms and from celebrities including Ashton Kutcher.

In June, 2014, they raised an additional $25 million valuing the company at $100 million. Immediately after that, David and Chrys sold a portion of their personal stake in the company without telling anyone for $6 million and bought a Ferrari (somewhat ironically their employees later found out about this secret transaction on their own app - an app titled Secret).

By the end of the year the company was already beginning to wind down. Usage numbers had dropped, employes were departing to other firms and Chrys Bader himself departed. In April, 2015, the company shut down for good and ceased to exist.

All in all Secret existed for around 450 days and burned through over $33 million dollars.

The story of Fab.com

In June, 2011, fab.com, an e-commerce site, raised $8 million dollars less than two months after launching (again Ashton Kutcher was one of the investors…not a strong track record). In December it raised a further $40 million and in July, 2012, a year after founding, it raised another $105 million in a round that valued the company at more than a billion dollars.

Fab proceeded to burn through $200 million in just two years. They hired too many people, they tried to expand into Europe before they were ready to, they rented expensive office space in a trendy area of New York City, and they spent $12 million to sign a ten year lease for a wear house that eventually was shut down. Like many start-ups, Fab focused too much on expanding as quickly as possible and not enough on generating revenue through sales to cover the costs they were incurring.

In the beginning of June, 2013, the executives at Fab realized that the company was over extended and might be in serious trouble. They called a meeting to discuss a plan to turn the situation around. Their answer? Spend more and try to expand even faster. The following passage from a Business Insider article on the company highlights this misguided psychology that drives all bubbles.

Just as ponzi-schemes require constant influxes of new investor money to remain sustainable, Fab had reached that point as well. Unfortunately for them, they discovered that the capital was much harder to raise than they had anticipated and the house of cards came crashing down. This year Fab, once valued at more than a billion dollars, was sold for $15 million.

The story of Jet

Incredibly it appears that the story of Fab is repeating itself in front of our very eyes in the form of jet.com. Jet, an e-commerce start up that has been valued at $600 million before it has even launched, has raised $225 million this year and plans to take on Amazon's dominance in the e-commerce space. Their own business model admits that they will have to spend as much as $300 million over the next five years to support an outside merchandise-buying program before they become profitable. In the words of the Wall Street Journal:

More than just about any other current startup, Jet seems reminiscent of the dot-com boom era, when e-commerce companies assumed giant losses before breaking into the black

The website, which launched just this week, is already in talks with investors about raising an additional round of several hundreds of millions of dollars. It is believed that this round would value the company at $3 billion.

The most bizarre part of the story is yet to come. Jet's business model sounds as if it was directly inspired by the fictional Milo Minderbinder's M&M Enterprises which famously (somehow…it is never explained how) makes vast sums of money by selling inventory at a loss in Joseph Heller's satirical novel Catch-22. In order to have prices that undercut its competition, Jet is currently buying products directly from the websites of retailers like Walmart and Target and then selling it to the customer at a huge loss to themselves. Take a look at this passage from the Wall Street Journal:

For example, The Wall Street Journal recently bought 22 items from Jet. Twelve were shipped to the Journal by retailers such as Wal-Mart Stores Inc., J.C. Penney Co. and Nordstrom Inc., according to sales receipts.

Jet's prices for the same 12 items added up to $275.55, an average discount of about 11% from the prices Jet paid for those items on other retailers' websites. Jet's total cost, which also includes estimated shipping and taxes, was $518.46.

As a result, Jet had an overall loss of $242.91 on the 12 items.

For a clearer understanding on how one might make money by losing money, I suggest we turn to Milo Minderbinder himself:

"But I make a profit of three and a quarter cents an egg by selling them for four and a quarter cents an egg to the people in Malta I buy them from for seven cents an egg. Of course, I don't make the profit. The syndicate makes the profit. And everybody has a share," Milo said.

Milo Minderbinder, a satirical parody of the archetypal money-obsessed business mogul, might not find himself too out of place in today's Silicon Valley.

The larger picture

When viewed together in a larger context, the stories of Secret, Fab & Jet begin to appear as chapters in a worrying narrative of what is currently happening in Silicon Valley. It is a narrative tied together by the common themes of hubris, greed, narcissism, irrationality and denial. While many investors still dismiss talk of a tech bubble, these stories are unmistakably similar to many that came out of the dot-com bubble. Many of the same patterns and practices seem to be occurring just as they did in 1999-2000.

During the dot-com boom the buzzwords were "Growth over profits" and "New Economy." Today those words might have been replaced with ones such as "Disrupt" or "Sharing Economy," but these new words are still fulfilling the same function - they allow us to convince ourselves that the world has somehow changed in a way that we don't quite fully understand and that we are now living in a new world where the rules of yesterday no longer apply.

The same logic is what drove the Dot-Com Bubble, and just as in 1999, it appears tht once again common sense has gone out the window.

For those of you who are still unconvinced, I leave you with the graphic below.