The Industrial Revolution brought about new ways of making things at the same time as it brought about new ways of injuring yourself.

Here are some bleak as hell examples of what went wrong in Victorian jobs as told through specimens from London's Barts Pathology Museum.

Scalp (1933)

This scalp was previously attached to the head of a 14-year-old girl who worked in a box factory. While scrubbing the floor in the workroom her ponytail got caught in a revolving shaft which picked her up, spun her round, and dropped her to the floor, minus her scalp. After receiving first-aid treatment she was taken to the hospital where the clinical notes state that “the scalp arrived half an hour later, and was too large and dirty to be sutured on”. Five years of treatment and skin grafts followed and the girl was finally fitted with a wig. (Technically not a Victorian specimen, but illustrates a Victorian problem.)

Thumb (1852)

The thumb of a boy which got caught in a machine and torn off with the tendon and some muscular fibres still attached. Aside from a broken arm and a missing thumb, the patient recovered just fine.

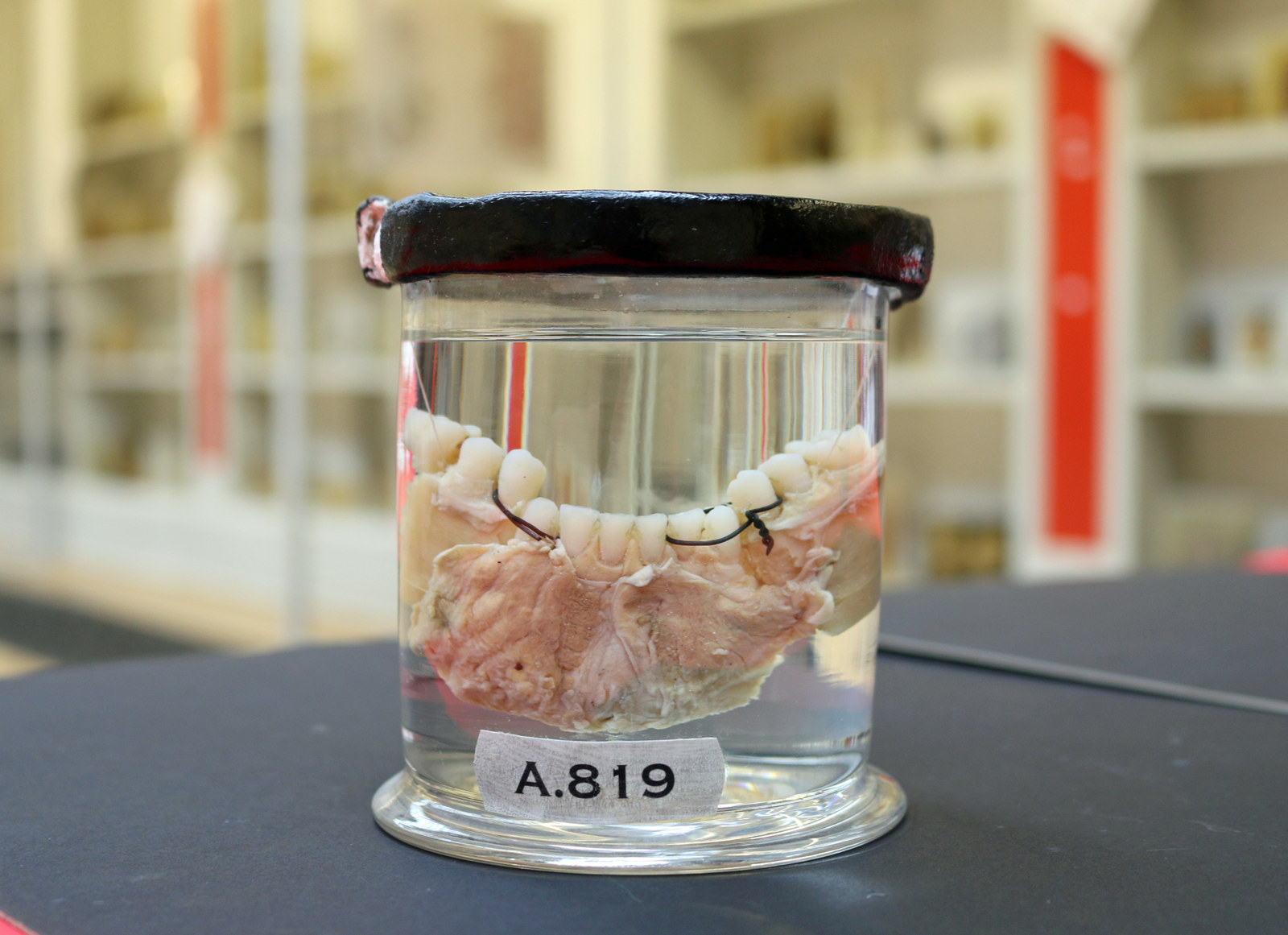

Fracture of mandible (1886)

From a 14-year-old boy who was caught between the rollers of a rotary printing press and died a week later from his injuries. The jaw is broken in two places and the jaw was wired before he died, which means he lived with a mouth like this for a full week.

Carcinoma Following X-Ray Dermatitis (1907)

When the x-ray machine was introduced in 1895 there were widespread reports of burns and hair loss from scientists and physicians. A shorter exposure time (now seconds as opposed to the 25 minutes of the past) and shielded cubicles for radiographers mean that no one has to end up with a finger like the one above just for turning up at work every day.

Fun fact: the guy who invented the x-ray machine, Wilhelm Röntgen, tested it out for the very first time on his wife's hand. When she saw the photo of her skeleton she said: "I have seen my death."

Chronic Phosphorus Osteomyelitis (1865)

An example of a problem called phosphorus necrosis of the jaw ("phossy jaw"), removed from a 35-year-old man who had worked in a Lucifer match factory for 20 years. The jaw was removed in two parts during one operation and the guy recovered.

It was an occupational hazard for people who worked in Victorian match factories because of a chemical called white phosphorus. It produced a better kind of match than the previous kind – which were wildly unreliable, smelly, and a bit explodey – but was worse for the people who actually had to work with the new chemical to make them.

It would begin with painful toothaches, swelling gums, then the jaw bone would start to abscess and glow a greenish-white colour in the dark. The seriously brain-damaged patient could be saved by removing the jaw, but if left alone they would end up dying of organ failure.

Weird fact discovered through this particular patient: human jaws can regenerate.

The patient was discharged from the hospital six weeks after the operation, but died suddenly on his first night at home, apparently of suffocation. His regenerated jawbone (below) was removed after he died, and is shelved in Barts Pathology Museum next to his original one. If there is another museum with two jaws belonging to the same guy, we want to know about it.

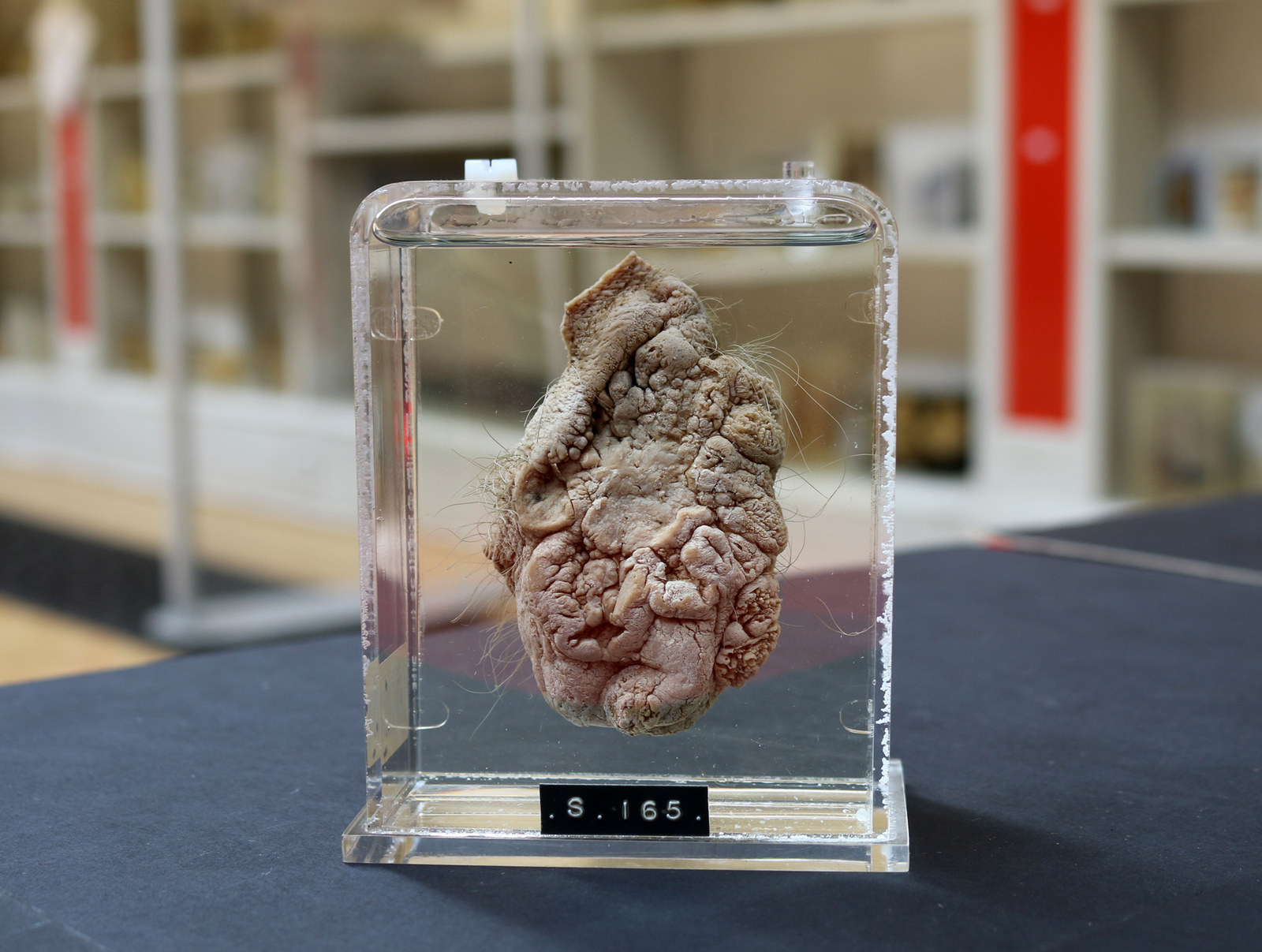

Chimney Sweep's Cancer (c. 1846)

A portion of the scrotum of a chimney sweep showing an epitheliomatous ulcer.

Sweep's cancer was the very first malignant disease to be connected to a specific occupation, a link discovered by Percivall Pott, a surgeon who worked at St Bartholomew's Hospital in the 18th century. It was a major discovery, and led to the health and safety regulations that save our balls today.

Carla Valentine, the technical curator of the Barts Pathology museum, explains why this is a very specific chimney sweep disease, and a very specific ball-related disease, in her YouTube series, A Potted History Of...:

Many chimney sweeps didn't survive into puberty, but those [that reached] their 30s or so, would get a sore on their scrotum and they would call it a "soot wart"... The reason it affected the scrotum is because the scrotum is a fairly wrinkly environment and the soot itself would get caught between the wrinkles. Sweeps didn't really wash, they were obviously very poor, so all this soot wouldn't get washed out. It would become an irritant, and it would eventually cause cancer.

Carcinoma (1808)

A cancer very similar to the chimney sweep's, found on the hand of a 49-year-old gardener who was employed to sprinkle soot over the ground. His condition got worse in the spring of the two years he was hired to do this job, but continued to grow after he was no longer sticking his hand in soot on a daily basis. After the hand was removed he was a totally fine one-handed gardener.

All these pots and 5,000 more live in the beautiful Barts Pathology Museum in West Smithfield, carefully restored and looked after by Carla Valentine who runs a YouTube channel on potted specimens that you'll really like if the above post didn't ruin you for life.