Ten thousand years ago, the prehistoric woolly mammoth disappeared from its mainland ranges — killed off by climate change and by the hands of our hunter ancestors.

Although a number of mammoth herds did manage to survive on isolated islands for several thousands of years after, the woolly mammoth has since become entirely extinct.

But in Siberia, where it is believed that millions of mammoth tusks remain buried in the melting permafrost, a new industry of ivory trade has taken hold.

Photographer Evgenia Arbugaeva, who was on assignment for National Geographic, traveled to Siberia to witness firsthand the working environments of those who still hunt for the elusive woolly mammoth.

While the international trade of elephant ivory continues to remain illegal, the trade of mammoth ivory has since transformed into a booming economic cornerstone for the region.

And a tusk hunter can earn a paycheck of more than $60,000 for each mammoth tusk they find.

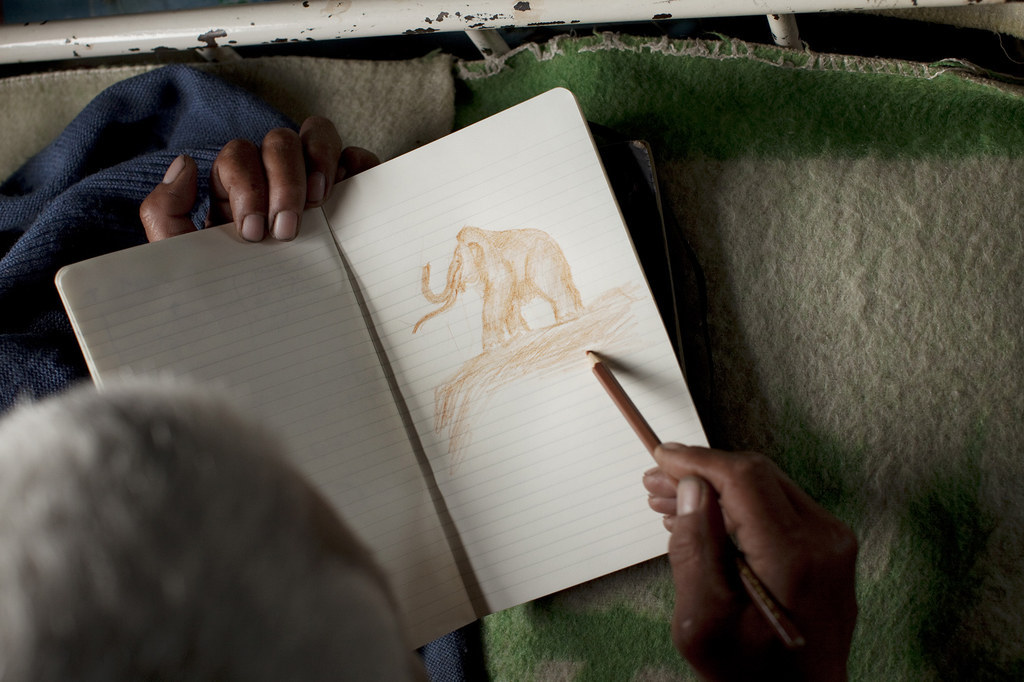

Here, Evgenia photographs Slava Dolbaev, a tusk hunter in search for woolly mammoths on the eroding coasts of Bolshoy Lyakhovskiy Island.

The eroding beaches of Bolshoy Lyakhovskiy Island provide fertile territory for discovering recently unearthed tusks.

Once found, each tusk can take anywhere from several hours to several days to fully remove from the thick layers of earth and ice.

Once excavated, the ivory tusks are hauled away on boats and gathered at the hunter's base camps, where they are then prepared for shipment to buyers.

It was reported by National Geographic that over 90% of mammoth ivory extracted from Siberia — roughly 60 tons every year — will eventually find its way into the Chinese marketplace.

A lucrative business despite being once considered a bad omen to disturb the bones of these ancient creatures.