"If the army is used against the Queensland Police, it will be considered a declaration of civil war."

John Fihelly was a cabinet minister in the Queensland government in 1917. In late November of 1917, he, along with the Premier and other cabinet ministers, in deadly seriousness, planned for the outbreak of civil war in Brisbane.

They organised for two thousand Special Constables to be sworn in, to reinforce the existing 400-500 police officers if it came to conflict with the 600 soldiers stationed in Queensland.

With these plans in place, outside the Government Printing Office, at 2am on the 28th of November, 1917, Brisbane almost went to war with Canberra.

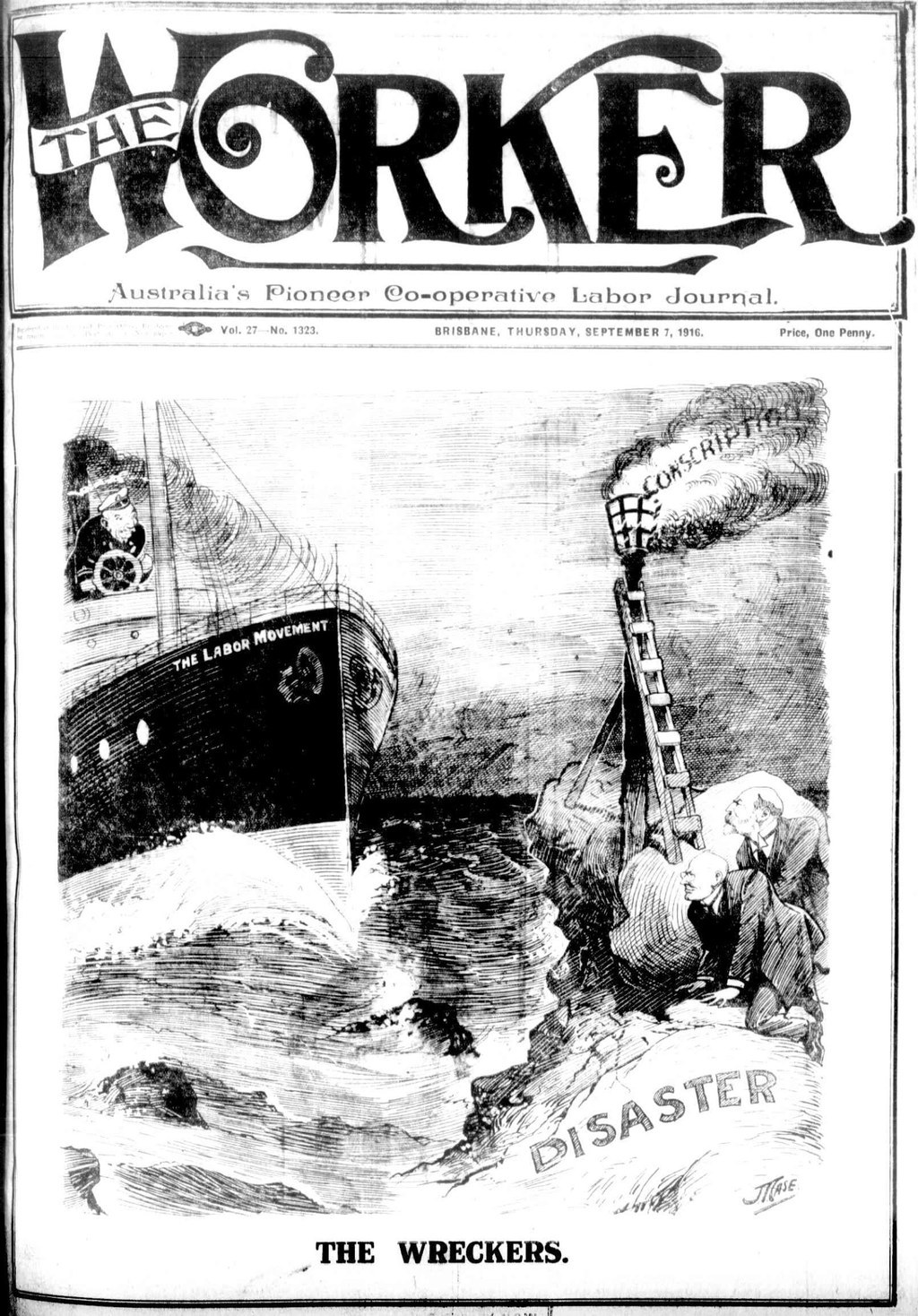

This extraordinary state of affairs had been brewing for years. In the middle of World War I, Brisbane had been having a vicious and divisive war on the home front. Over two referendums on conscription, conflicts over class, race and ideology played out. In the end, conscription lost, and Queensland ended up with the label the 'most disloyal state in Australia' (Evans, 59).

This is the story of how Queensland earned that name.

The war within and without

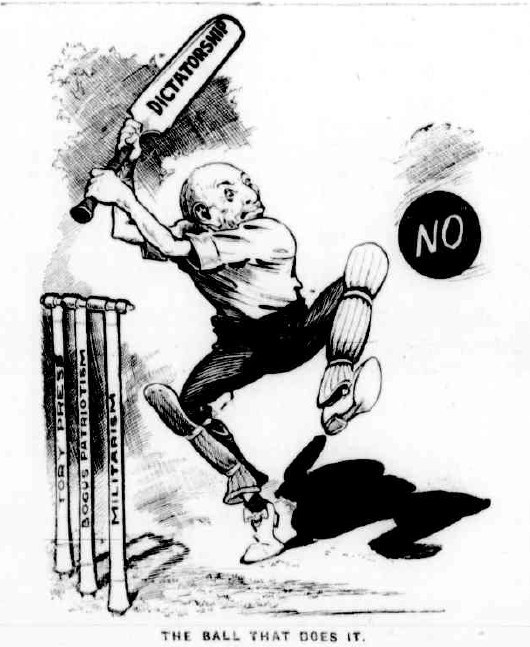

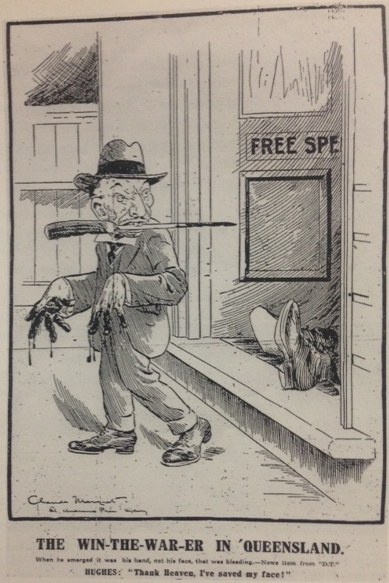

Billy Hughes (pictured in the first cartoon) was the Labor Prime minister, the 'Little Digger' who proved to be an admired wartime leader, a position to which he was well suited. As a long term advocate of conscription, he spearheaded the scheme to have all boys undertake military training from 1909, and on a trip to London he had been convinced by the British Imperial War cabinet that Australia must compel these conscripts to serve overseas. His problem was that the Labor party had a strongly anti-conscription majority.

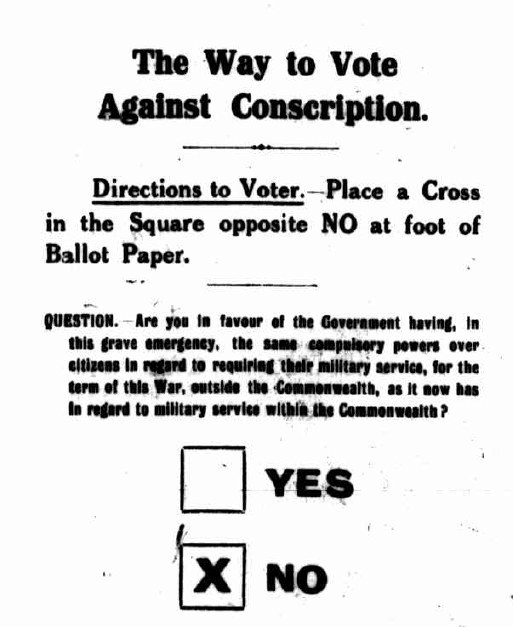

Unable to wrangle the votes in his party caucus, specifically in the Senate, Hughes was forced to a compromise position — he put the issue to a public vote, a plebiscite on whether or not Australians would be compelled to serve overseas, and started hustling votes for the "Yes" campaign.

This was Hughes' masterstroke, gaining a mandate for a policy he supported, putting the industrial labour movement in its place, and showing those he felt were disloyal in the caucus that his way was the way to success. If it had worked, it would have been a triumph. But all that he succeeded in was to take the conflict from the caucus rooms and conferences of the Labor party to the streets and the ballot box.

By campaigning for 'yes', he set himself against the political machine of the Labor Party, the Irish immigrant population who were less than enthusiastic about going to war for the British Empire, various pacifist radicals, religious groups and socialists; and in Queensland, he set himself against Premier Thomas Jordan Ryan – the leader of the most successful Labor branch in Australia; Brisbane Trades Hall, Irish and German immigrants, and radicals like feminist Margaret Thorp. For this, Hughes was cast out of the Labor Party, and took many of its parliamentarians when he left.

This was a deeply felt personal and political divide. E.J. Holloway, a Labor member of the first parliament told the story of the funeral of Senator Andrew McKissock in Victoria in 1919. Standing fifty feet away from the crowd of hundreds of Labor mourners was William Spence, a loyalist to Hughes who still felt the distance of the conscription conflict years later.

Workers of Australia, divided

“A man cannot hate to order” (The Worker, 1916)

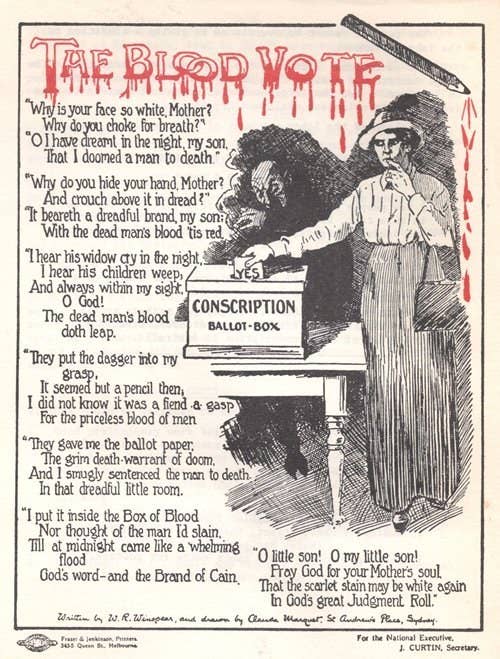

The appeal to the better nature of working class Australians was a genuine one. A letter to the Worker read:

"Tolerance, love of freedom, the right of every man to think for himself, to speak the thought within him whether hedged by friend or, foe these are the things that have made England great. Are we to part with them for the sake of adding a few hundred unwilling, and therefore utterly useless, conscripts to our army of four million men?"

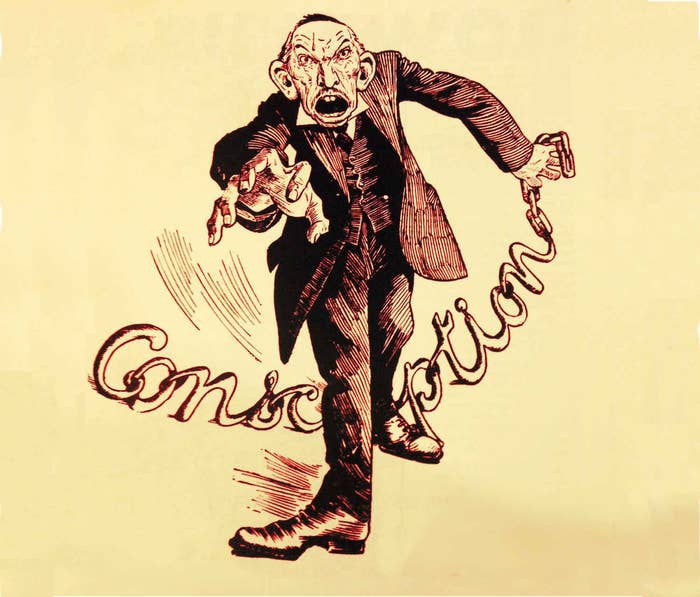

Anti-conscriptionists published many articles leading up to the vote regarding conscription, chief among their concerns the inequity in what was being asked from different classes. A major rhetorical theme was the voluntary nature of the contribution of wealth to the war effort, without an attempt at conscription. As well as this, the poor pay of soldiers fighting at risk of loss of life and limb showed that voluntary recruitment had not failed. They argued that a volunteer at the front was worth a lot more than reluctant conscripts, who would also not be able to help the war effort at home. This voluntarism was genuinely felt and demonstrated by the 30,000 members of the AWU who joined the Australian Imperial Force.

The fear of 'economic conscription' was also a motivator for the labour movement – not only were there attempts to enforce conscription by law, but conscriptionists advocated measures such as dismissing all working men of fighting age so as to force them into armed service. This was what was referred to as 'economic conscription'. There was also serious discussion, after the 1916 referendum was lost, to dismiss unmarried public servants under 25 to force their service.

These economic concerns galvanised the union movement, and tied in with the ongoing concerns of a small, white, colonist nation in Asia – the anti-conscriptionists used concerns about 'coloured' labour taking jobs from white Australians, when they were conscripted overseas.