I currently become dangerously emotional when thinking about a press conference given by a tennis player. Half of the reason for this is coincidence. The other half is because the last week in the life of the tennis player, the just-retired 33-year-old James Blake, captures the entire difficulty of existing as an adult human, and I don't think you even need to know anything about tennis to see where I'm coming from.

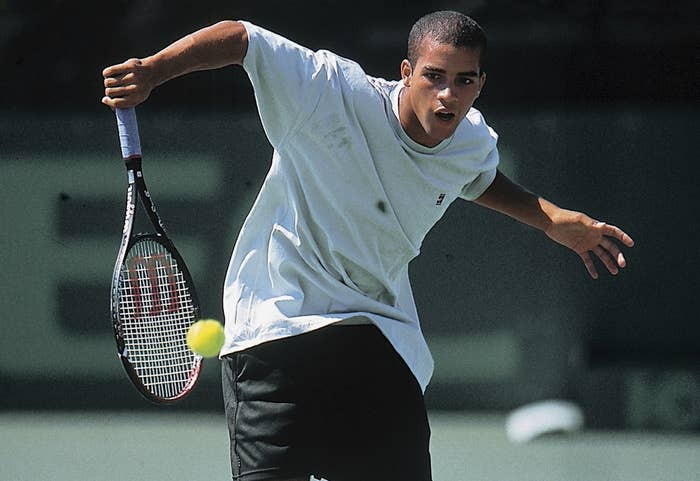

First, the coincidental part of it. I like James Blake because of something that you might find unsympathetic: He and I both went to Harvard. Let me try to make it slightly less unsympathetic: I first heard of James Blake because the year I started Harvard, as a 17-year-old from Michigan, was the year he left Harvard to turn pro. This was still when I thought of Harvard as a magic dream space where all the weird kids who actually liked books and math and extracurricular activities went after getting through high school. I heard Matt Damon had gone to Harvard, and I thought that was awesome. I heard about this guy James Blake who was a great tennis player but also apparently liked books and math and learning enough to go to Harvard, and I thought this was awesome as well.

The point is that James Blake reminds me of a hopeful time in life. He was a quasi-cousin — a mascot for overachievers — someone whose progress we all checked in on from time to time. A larger-than-life figure even to Harvard dummies who like to make a big deal out of how hard they are to impress.

We weren't the only ones following him — he was a young and talented American player in what is still a down era for United States tennis, so he had a lot of hopeful fans. But he could be frustrating. Blake was always a player capable of beating the best in the world on any given day. He would win smaller tournaments and pull off an occasional impressive upset and was generally discussed as someone with the potential to be a major star, ranked as high as No. 4 in the world at one point. Yet he never had a signature triumph. He never got further than the quarterfinals of a major tournament. He often lost in five sets in the most stressful ways possible, most famously to Andre Agassi in the 2005 U.S. Open quarters. Blake led that match two sets to zero and ended up going down in a fifth-set tiebreaker, which itself was a tragically close 8-6 kick in the stomach.

His career just never seemed to click into place the way the instructions that came with the package said it was supposed to. And it did really seem like Blake was supposed to have an epic career, given his story. He was born in Yonkers, outside New York City, and as a kid played at — and heard Arthur Ashe speak to — a Harlem junior tennis program that his parents worked with. That's an auspicious start for a black American tennis player (his father Thomas was African-American and his mother British). Then there was the Harvard thing, which tends to raise the stakes of any given pro athlete's career. In 2004, in the midst of Blake's career, he hurt his neck badly diving for a ball. And developed a debilitating case of the disease shingles. And lost his father to cancer. Three huge blows in the span of a few months. In 2005 there was the painful loss to Agassi. The mythic origins, in combination with that terrible mid-career stretch, made it seem predestined that he'd eventually sometime come out on top. It felt so obvious as to be a matter of physics. James Blake was gravitationally bound to win a U.S. Open title. But despite putting together the best streak of his career in 2006, he never threatened to win a major. Just when it seemed like everything was coming together, something would come apart. You may know the feeling.

It was sometime around 2007 that I had a brief personal run-in with the man himself. A friend of a friend was having a birthday party. Blake had apparently been roommates with someone who knew the person celebrating, and at one point early in the night he showed up at the party. I remember him standing at the edge of the room, drinking a glass of water and watching the dance floor. He stayed there for a while as his friends came over to say hello. He seemed like he was in a good mood, but well before midnight he put down the water and left — someone said he'd be up at six the next morning to train.

I thought of this last week watching Blake's press conference after the loss to Ivo Karlovic that knocked him out of the U.S. Open for the last time. "One thing that's different about our lives as athletes is that we're always pro athletes," he said. "Even when you feel like you have time off, you still have to be training. You can't be always going out until three, four in the morning like your buddies can once in a while because they just have to be in at work and can get through it with a couple cups of coffee. You can't fake your way through a tournament. You're on a pretty selfish schedule. I'm looking forward to not having that."

The press conference was a heavy thing — a guy seeing a three-decade life project come to a end in a largely empty stadium after midnight. There was a lot to think about: fans coming to terms with an unsatisfying end to Blake's career, Blake coming to terms with an unsatisfying end to his own career, and (perhaps, if you're in the mood to brood) fans thinking about the similarities between his life and their own. Thanks for speaking to us, James. Can you tell us what you feel like right now? Can you describe what it's like to know conclusively that you will never have the thing you wanted most? Can you talk about your forehand, your serve, and the way that every day your life's possibilities get incrementally narrower? How did your legs feel in the fifth set, and don't almost all of us have to admit eventually that we aren't going to be the ones who get lucky?

These are questions everyone has to figure out a good answer for. And there are small, mostly hidden parts of all of us that never really let go of the idea that the answer is simply that we were born for a more glorious destiny and there has been some sort of mistake, which is why Bruce Springsteen songs are popular. In any case, most people get decades to coherently balance their ambitions and their happiness. In some sense, Blake had the five minutes between his loss and his press conference. We've all admitted to someone we respect that we haven't lived up to their expectations. Imagine admitting that to hundreds of thousands of fans who have hopes for you because you are better than them, because you are their avatar, livin' the dream.

To him, it was all fine. He was weary, but he held his head straight and spoke clearly. He had done the best he could. "I'm never going to have 20,000 people cheering for me [again], chanting 'U.S.A.,' screaming my name," he said. But: "I'm lucky enough to have had that for 14 years. Most people have never had that. Now I'm going back to being a normal person...changing diapers and hoping to get 18 holes in on a given day, and that's OK with me."

He talked about his history with the U.S. Open. "I've had a good and long journey —since I was a kid sneaking in here to being a full-grown man leaving here. I've had a lot of people that have helped me become that man, and I'm hopefully someone my mom is proud of, my friends and family are proud to call a friend or a brother or a husband. That's hopefully what I'm most proud of when I do leave here for the last time — as opposed to just the wins that I had here."

It might have gotten a little dusty when he talked about hoping his mom was proud of him.

He went on: "In terms of the cards I got, I can't complain. I got up to [number] four in the world. I appreciate that people gave me credit for being a better athlete than I deserved. It was the hard work that made me look athletic and made me look like I was that graceful or that fast. That was from hours and hours on the track. But, I mean, I got to four in the world, so I had to have some pretty decent cards. I definitely did the best I could with them. I played them the way I could."

The whole thing was a big shrug. "I don't know what I'm going to say honestly in two weeks. Am I unemployed? Am I retired at 33? Am I in between jobs? It's going to be interesting. But I'm looking forward to just relaxing and seeing what comes." James Blake, to an extent that the rest of us can hardly imagine, stared into an abyss of unrealized hopes and said, "Eh, you can't win 'em all. What's next?"

I like his style. Hey, James: Put your glass of water down and come on out on to the dance floor. Out here, we're not any more sure of where we're going than you are. But we're all in it together.