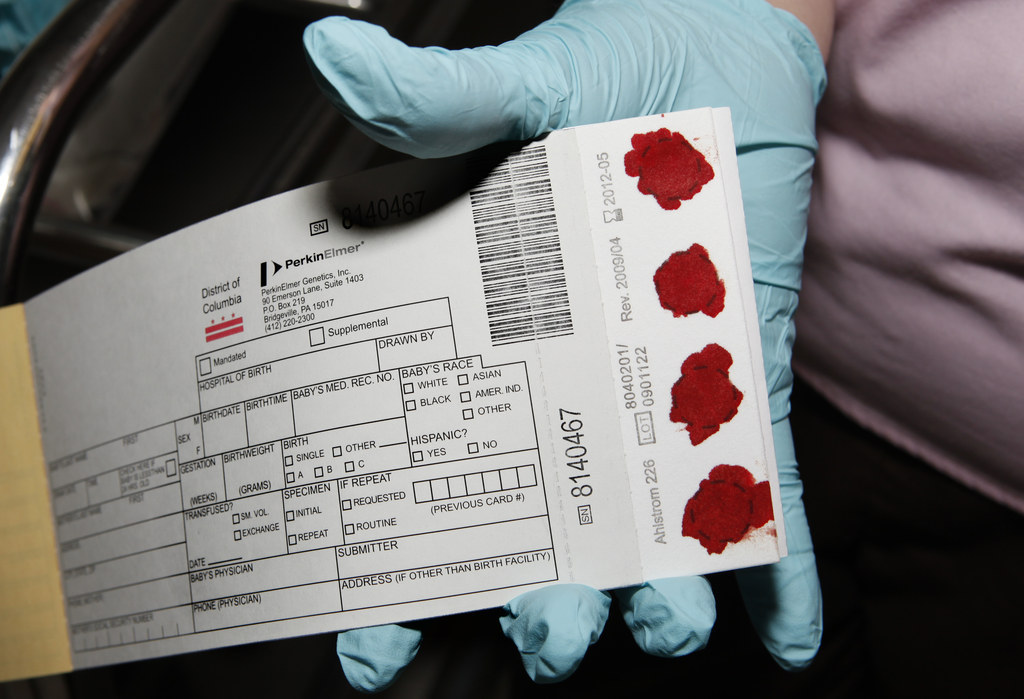

On the day they're born, nearly all American babies have their heels pricked with a needle. A few spots of blood drip onto a card with the infant's name, and that card is rushed off to a lab to test for about 40 genetic diseases.

Amidst the chaos and elation of the birth, the baby's mother receives dozens of pamphlets, including one about this testing, and possibly a form to sign. At that point, in many states, the baby's blood becomes government property. States put it in long-term storage and, often, provide anonymized samples to medical researchers for their studies.

The new parents, meanwhile, usually have no idea that any of this is happening. But that's about to change.

This week, a federal act goes into effect requiring that all federally funded researchers using newborn blood spots first get parental consent. Meanwhile, today California lawmakers opened debate on a bill that would extend this to any research — whether federally or privately funded — using the samples, which could change how parents are informed about the program in the first place.

"I talked to, like, 50 parents," Mike Gatto, the California assemblyman introducing the Newborn Blood Sample Privacy bill, told BuzzFeed News. None of them, he said, knew that California had banked their baby's DNA and handed it over to scientific research. "I don't mean to sound alarmist," he added, "but this really does become a situation with a state-created DNA bank, with profound room for abuse."

On the other side of this debate are scientists who argue that such legislation stirs up unfounded fears around newborn screening, which could ultimately put tens of thousands of infants at risk.

Newborn screening is widely praised as one of the great success stories of public health.

"Along with immunizations, it's one of the most successful public health programs in our country's history," Erin Rothwell, associate professor of medical ethics at the University of Utah, told BuzzFeed News.

Screening programs for rare but treatable genetic diseases in infants began in the 1960s, and the program now identifies nearly 3,400 infants with these diseases every year. For example, the first genetic condition to be screened in newborns, phenylketonuria or PKU, can cause mental retardation if left untreated. But when diagnosed early, there's a relatively simple fix: The child can be put on a special diet that promotes healthy brain development.

The controversy lies not in this initial testing, but what comes after. In many states, parents are not explicitly told what happens to the blood samples. Consent forms are often long and difficult to understand, and that's if they get read at all. "People don't understand what they're signing, they won't take the time to read it. You have other pressing needs," Rothwell said.

Approximately 20 states store and distribute the samples, operating under a messy hodgepodge of rules and regulations. The laws give parents varying levels of control over how the blood spots are used and whether they will be told about it.

In 2009, five families led a lawsuit against the state of Texas for storing the blood spots and using the samples for research without parental consent. An investigation by the Texas Tribune revealed that the state health department had shipped 800 blood spot cards to the U.S. military to help build out a vast DNA database for use in forensic investigations. After losing the suit, Texas was forced to set fire to nearly 5.3 million blood spot cards.

In 2012, after a similar lawsuit, the state of Minnesota destroyed all of its samples as well.

The new California bill came about partly because of what happened in Texas and Minnesota.

The first version of the bill allowed parents to easily opt out of the screening itself. But anger from the medical and scientific communities spurred Gatto to scrap the bill's wording for something less alarmist. The law now calls for a consent form that explicitly informs parents about the potential research uses, and allows parents to check a box to opt in. Another box allows parents with any religious restrictions to request more information before the screening.

These changes, if passed, aren't likely to dramatically affect the number of parents who get their newborns screened. But scientists worry that it may curb the number who consent to donate the samples to future research. This could potentially be a huge loss in a state like California, where blood from the 500,000 infants born each year provides a large and diverse swath of data for understanding things like the effects of environmental toxins on infant health, and for developing tests for additional genetic diseases. It's a rare opportunity for researchers to have a data set as diverse as the entire population of California, Rothwell said.

"I see this bill as being destructive of what is a superb, reliable, and responsible program that California should be very proud of," Robert Nussbaum, a professor of medical genetics at UCSF who uses the blood spot data in his own research, told BuzzFeed News.

Nussbaum also believes the privacy concerns are overblown. So far, he pointed out, there haven't been any security breaches reported in which data was lost or revealed a baby's identity. "There's a radical privacy streak that is driving this bill, and I think it's a terrible idea. I will fight it as hard as I can."

The new law may indeed impede scientific research, Hank Greely, professor of law and bioethics at Stanford, told BuzzFeed News. But research interests shouldn't necessarily trump parental choice, he said.

"My view is, that's life. It would be great for scientific research if we could take all identical twins, separate them at birth, and raise them in perfectly controlled circumstances. But we can't! And that's a good thing."