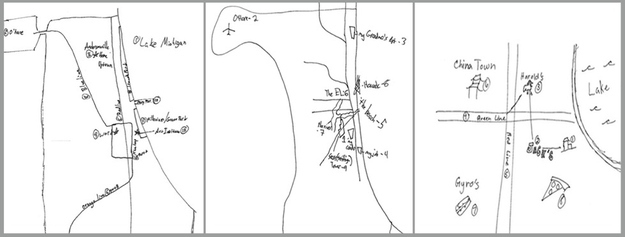

Last summer, researchers from Motorola Mobility and the Mobile Life Centre in Sweden asked people in Chicago to draw a map of “their” city with only the places most important to them. About a fourth were tourists; the rest locals, ranging from savvy teenagers to the technologically illiterate. But the hand-drawn maps were largely the same: They were highlighted by parks and the arts, not nightlife or food-related venues.

“A lot of location-based services are really focused on specific places and venues, a bar or a club or a certain building,” Henriette Cramer of the Mobile Life Centre told me. “But all of the things between venues come up a lot when you ask people to tell you about their city – ‘What do you love? What do you?’ It’s not just a venue, it’s the spots between venues and personal stories that really matter.”

But on Foursquare, parks and outdoors accounted for only about two to three percent of check-ins — the arts, less than one percent — at the time of the study, said Motorola Mobility's Frank Bentley, though they made up more than 40 percent of the places on people's hand-drawn maps. This isn’t entirely Foursquare’s fault, because check-ins are based on users, but Foursquare does prime us with its Top Picks — suggestions generated more by the places people (your friends) go often, not the places that are necessarily the most meaningful.

Even though grandma's house matters more to you than a bar (I hope), it doesn't really belong on a something like Foursquare, said Andrew Hogue, Foursquare's head of search. "Foursquare is trying to be the inverse of what those maps are — rather than show you places you're already familiar with, we want to show you places you've never been," he told me.

Hogue said they are starting to see Foursquare recommendations move away from just eating and drinking as it gets a richer signal of how people behave. "Three years ago it was very nightlife heavy, which is still a core use, but we’ve definitely seen a shift with more suburban users and those not in their twenties," he said — and people outside of cities are more apt to check in to places other than bars and restaurants. Hogue added that in the past three years, Foursquare has gotten a much better pulse on what people want — that sunshine means more parks and ice-cream shop suggestions, and at 9 a.m. we don't want a list of bars.

The Motorola research builds upon social psychologist Stanley Milgram’s work on “mental maps” that analyzed people’s perceptions of 1970s Paris. The researchers wanted to see if the pervasiveness of mobile technologies might’ve changed our mental maps.

The researchers expected people to draw maps differently based on whether they used GPS or location-based services or good-ol’ paper maps, but technological aptitude and demographics had little effect. Food, work and shopping — the top three categories on Foursquare — represented only 12.5 percent of locations drawn. However, people that used check-in services tended to draw a larger portion of their city, suggesting that location-based services cater to explorer types.

One distinct difference between the maps, though, was that tourists used more landmarks, whereas locals used the actual neighborhood names — something that is largely overlooked by most location-based services, the researchers said. They think these services could use more visual clues to create better (or even two separate) maps for tourists and local residents, and change the wording too (since no one on the West Coast knows what a turnpike is, and people on the East Coast don't drive on freeways).

Foursquare has a function kind of like this — in the Explore tab you can search for a list of sites, which is "basically a tourist mode," said Hogue. For tourists in New York City, it'll bring up spots like the World Trade Center and Times Square, places that local residents don't want showing up on Top Picks just because a lot of people are checking in there.

The study was just a small sample in one city (they’re working on Stockholm now). But given the number of meaningless check-ins at Starbucks and Subway I often see, its ramifications could be significant. It's not very clear what encourages check-in behaviors — if it's for the mayorship credibility or super cool badges or fiscal incentive ($5 for Amex holders) — but ultimately, Foursquare users will benefit if people's check-ins more accurately reflect their lives.

Maybe the space for sentimental suggestions isn't meant for Foursquare though; perhaps pinwheel — Flickr founder Caterina Fake's location-based nostalgic notes project — will fill that void. I like Foursquare, but I'll like it even more if I keeping finding things like a list of hikes near New York City that detail where to find the sunbathing turtles — something that moves beyond just a list of places people have been to a list of places they've been and experiences they've had.