We've all done it – woken up feverish with some body aches, but given the current state of healthcare, we avoided calling the doctor's office altogether. After all we are intelligent, very with-it, and entirely capable of self-medicating – basically the equivalent of MD's without the expensive license. Looking into the medicine cabinet we dig out an unfinished round of antibiotics stashed in a dusty, faded orange cylinder. It doesn't matter that it was prescribed three years ago. To our mother.

This may be worrisome for a nation full of germaphobes, but we do live with bacteria in our guts, like the good bacteria that are discussed so casually as people shove yogurt in their mouths on probiotic commercials. Antibiotics are designed to kill bacteria. Antibiotic use (especially when not indicated), can deplete our good bacteria, making us more susceptible to opportunistic bacterial infections, such as Clostridium difficile infections.

________________________________________________________________

"Hold up -- a friend just emailed me that Katie Couric is talking about C diff. I just need to DVR this for later. Huh, she never has me to talk on her show, damn it," said Christian John Lillis with faux dismay. Lillis, who is the cofounder of the Peggy Lillis Foundation – one of only three nonprofits dedicated to Clostridium difficile awareness – lost his mother to it 3 years ago.

Peggy Lillis was born in Brooklyn, NY, into a large Irish-Catholic family— the third of nine children. Peggy became pregnant with Christian at 19, and shortly thereafter married his father.

"She was one of the warmest people I ever knew, but she was also razor sharp and honest," said Christian. "When I was a kid, I one time did the math that I was born only seven months after my parents had been married. I remember jokingly approaching my mom about it to which she replied, also jokingly, that abortion was legal and that I should be happy to be here."

Peggy and her husband split, and she, Christian, and her younger son Liam, ended up on welfare— "which, despite what anyone tells you, no one can survive on that," added Christian. But Peggy wanted more, a better life. She began waiting tables at a restaurant in Brooklyn while taking classes for her associate's degree. At 33, Peggy graduated and started work as a paraprofessional for the Department for Education –ultimately she became a kindergarten teacher after earning her bachelor's from Brooklyn College.

"You have this blonde Irish woman teaching in an inner-city neighborhood, where most of the children are of color with working-class families, or parents from the Islands, and she so related to them and excelled at her job, because of her own personal experience that hard work pays off," said Christian.

Peggy was nearly finished with her master's degree in education when she went to the dentist for a root canal. To fight off infection, Peggy was prescribed clindamycin, a very popular antibiotic. Five days later, she was suffering from severe diarrhea – severe enough that she took two days off at work.

"She was working six days a week, five days teaching and one day still waitressing on Sunday mornings. She loved having that cash for Christmas money. Or it was her Maui money," Christian said; He went on to explain that after his parents divorced, his mom had a boyfriend named Randy. They dated for years, even though that he eventually moved for work to Maui – she would visit him for 2 or 3 weeks every year.

"So for her to take off work was unusual."

Under the assumption that it was something contracted during contact with one of her 20 kindergartners, Peggy called her doctor and was prescribed antidiarrheal medicine. However, within days, Peggy was admitted to her neighborhood hospital after feeling dizzy and weak. Christian, his brother Liam, and their aunt, who was a nurse, were greeted at the hospital by the ER attendants and the head of the infectious disease department. They were seemingly surrounded by white coats.

"Quintupled blood count as a result of septic shock" one said.

"Toxic megacolon," said another.

"The cause is Clostridium difficile," said yet another.

"Clostridium difficile? But how?"

Clostridium difficile, or C. diff., is a bacterium that can cause symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon; until recently, it was thought to affect mostly the elderly (Peggy was only 56) and appears most commonly in patient care facilities, like hospitals and nursing homes, where germs are transmitted through touch or contact with infected equipment.

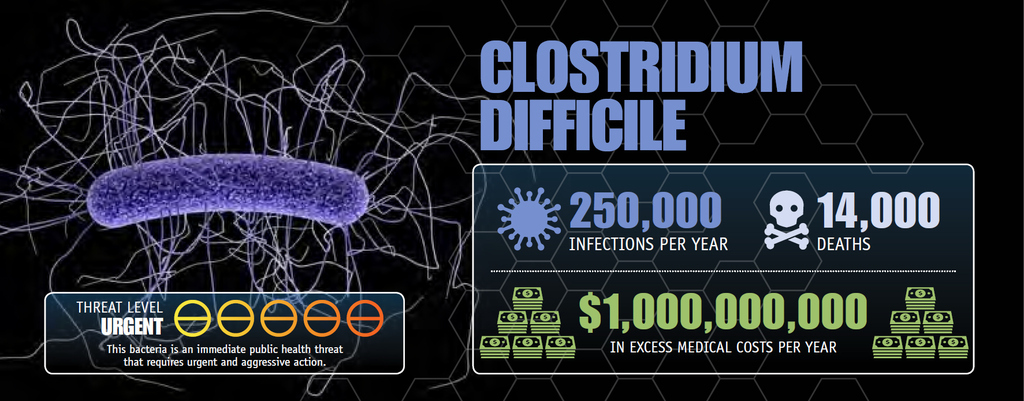

The number of people hospitalized for C. diff. has tripled in the past 10 years according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While other infections common at healthcare settings have been going down over the past decade, C. difficile infections are at historically high levels.

"Microorganisms are clever," said Dr. Ruth Carrico of the University of Louisville Medical School about how the C. diff bacteria have biologically adapted over time. "Bacteria have only two functions – to stay alive and reproduce. Can you imagine how adept we would be at those functions if we only had to concentrate on two things?"

The C. diff. bacteria are very good at these two functions: the CDC estimates that about 14,000 people each year die from these infections – people like Peggy.

________________________________________________________________

Within 36 hours of her admission, Peggy died, with more than 40 people waiting outside the doors of the ICU. "Basically, you had 40 people go out of their minds in that moment," Christian remembered. The Lillis family held a two-day traditional Irish-Catholic wake, with over 500 people signing the memorial booklet.

Once some form of normalcy was established in the weeks following Peggy's funeral, Christian wanted to find some kind of information about the infection that killed his mother – he got online, he read articles and journals – there were a lot of documented cases, more deaths are associated annually with C. diff than drunk driving, but there was no accessible information. He mostly found pieces written by doctors for other doctors.

"I remember being devastated and angry, how could so many people be dying of this? My mom had always taught us to be social justice minded, and I had worked in nonprofit management and fundraising for years, so my brother and I determined that our mom's death would not be in vain."

October 27, 2010 would have been Peggy's 57th birthday.

They celebrated her life by hosting a kickoff fundraiser for the Peggy Lillis Memorial Foundation for Clostridium difficile advocacy and education.

________________________________________________________________

About a block from the UofL Hospital, around 700 miles from Brooklyn, Dr. Ruth Carrico sits in her office. The University of Louisville has been selected as a study site for a clinical trial testing a vaccine designed to prevent Clostridium difficile infections, and Carrico will be overseeing the study and its results.

The vaccine –called Cdiffense by developers from Sanofi Pasteur, the vaccine division of the French pharmaceutical company Sanofi—is in the Phase III clinical program, which has just started recruiting volunteers for a randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center, multi-national trial that will include up to 15,000 adults at 200 sites across 17 countries, according to Marisol Peron, the Vice President of Sanofi Pasteur North American Communications.

Carrico's area of professional emphasis is infection prevention, coming from a health administration and nursing background. In addition to preventative measure that can be used by hospitals to stop Clostridium difficile outbreaks, Carrico is incredibly hopeful about the vaccine, which has been fast-tracked by the Food and Drug Administration, in preventing the spread of C. diff in the vaccine's target population.

Lillis, who has also worked with Sanofi, is also excited about the potential to make things better. Though he does not feel that the vaccine will be the only answer to C. diff., combined with prevention, treatment and awareness methodologies, Cdiffense has an important place in curbing C-diff deaths.

To further help the cause, Lillis says "the Foundation is seeking to train advocates and shape legislation." He hopes to ultimately have representatives in every state, approaching legislators about state tracking of Clostridium difficile numbers in hospitals and nursing homes, as most current numbers are self-reported, and perhaps skewed.

Another simple step for infectious disease prevention which both Carrico and Lillis stress—keep things clean. "When it comes to preventing infection, people need to go back to the basics. One of which is maintaining personal responsibility for immunization. Another is disinfection in medical settings," said Carrico.

What's the most basic thing, though?

"There needs to be general awareness of C. diff.," said Lillis. "My mother died of something that most people don't know exists, I didn't know what it was. That's really upsetting. But nothing happens, especially in this country, until a bunch of people get really pissed – and sometimes that's what it takes."

More info on C-diff can be found at www.peggyfoundation.org