Matthew Gray Gubler didn't want to show me his paintings. Since his own house was being renovated, the Criminal Minds actor was staying at his friend's house in Los Angeles; I asked if he'd been painting there.

"Nothing good, to be honest," he said, sitting in the shade in slippers. "I have nothing — nothing worth showing here, anyway, for sure."

"Can I see it anyway?" I said.

"It's so bad. I can't," he said. "Because I always worry about, not worry, but my nightmare is making someone see something in the flesh, and then making them, like, they feel some responsibility to pretend to like it. Like, 'Ohh.' Like you would be like this: I'd be like, 'Oh, here!' and you'd go like, 'Oh, that's great.' On the internet, it's this safe space where I can put it up and people can click on it or not. I don't have to be in the same room as them pretending to like it, so I very rarely show people things, and I've made the mistake — like, some people misinterpret my style of painting as offensive, and I've had instances where I've painted beautiful portraits for, like, a girlfriend or someone, and they're just like, they look at it with a grimace and they're like, 'This is terrible. I don't look like this, and you're awful, and you must hate me.' And I'm crushed by it, so I kind of am weird about being in the room when it's shown."

"Is my portrait up there?" I joked.

"It is," he said. His straight face is marvelous.

"OK. What if I looked at it and you weren't in the room?"

"Maybe, here's what I'll do. Let me think. How about this. I'll go up to that window." He pointed to a window in the house. "I'll open the window and I'll hold something out and I'll look away, and you (look) from here, and then I'll give it like, 'one-one-hundred, two,' like, four beats."

"OK," I said, which is how he came to be shouting down at me from a second-story window covered in vines, holding out his paintings and counting to four or five before he pulled them back inside.

And then when he came back down the steps, he was holding two paintings, which he placed on the table between us. He said he didn't see the creepiness of the blurred and long-fingered figures he paints, in part because he has a peculiar aesthetic sensibility.

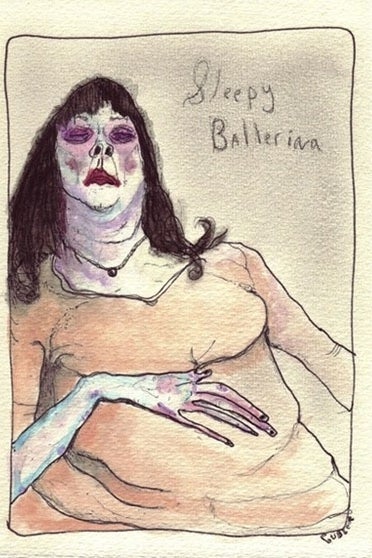

"This is my friend Paget; she's an actress," he said, gesturing to the painting with the words "Sleepy Ballerina." "This, to me, is like, the most beautiful photo of her, or picture of her, but again, I guess it is kind of creepy, because the watercolors make it smudged."

"It's the fingers," I suggested, looking at the long, swollen fingers. "Maybe the eyes." (Swollen, purple.)

"Yeah, it looks like blood, that's lipstick. I know," he said. "How do I explain it — I've had a lot of coffee, so I'm not (making sense) here, but people are — it's weird because you can't really describe it. Conventional beauty is as rare as being, for instance, a dwarf or something, so to me, it's on the same spectrum. It's as unique, and as beautiful, and so I've never understood why, just because someone has, like, big blue eyes, which is really rare, why is that more beautiful than someone having, like, really tiny hands, or some feature that's really unique and therefore very beautiful to me?"

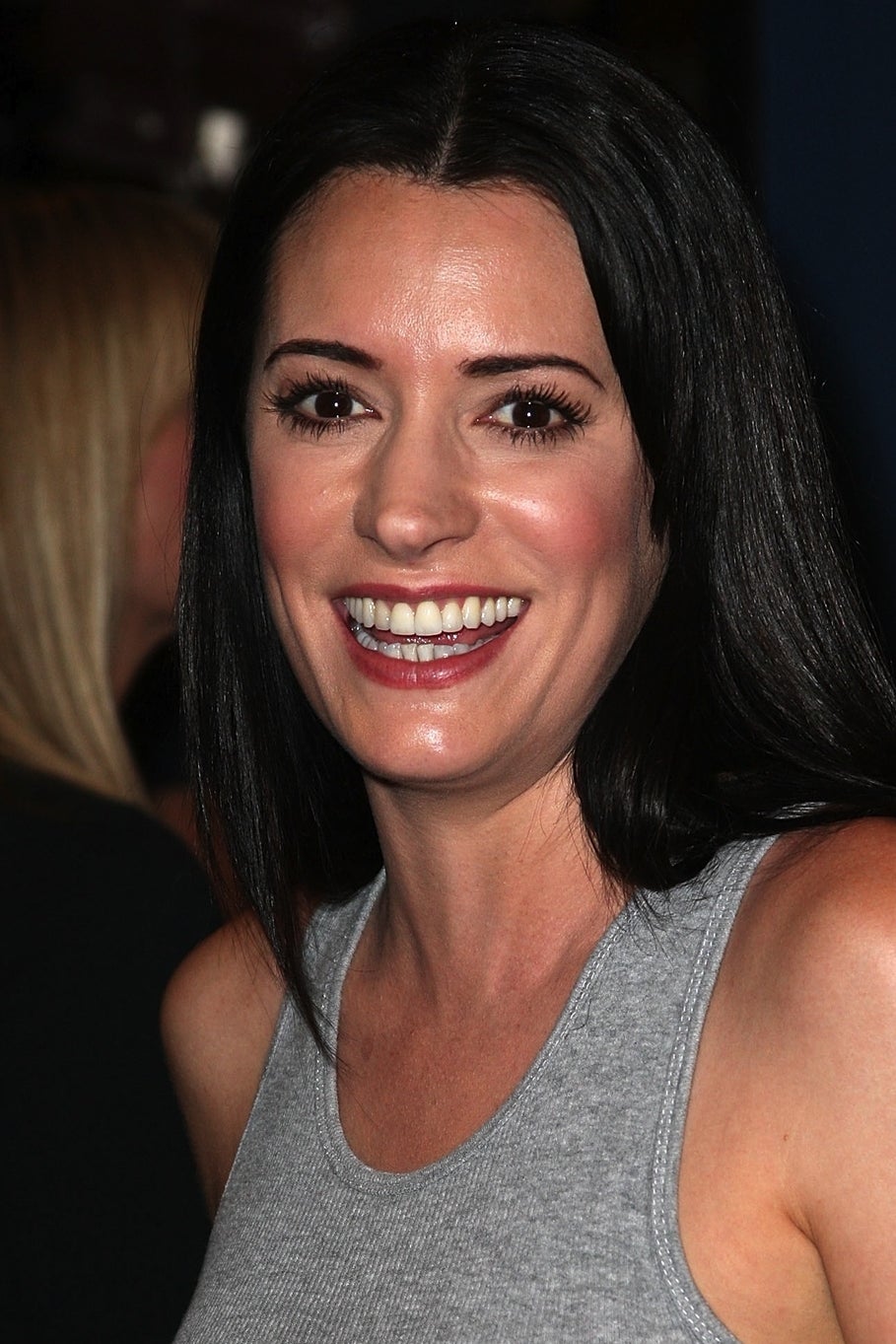

(Paget Brewster, an actress and former Criminal Minds cast member, has big brown eyes, although they are shut in the portrait.)

Gubler casts the atypical people he admires when he directs episodes of Criminal Minds, citing both their odd beauty and his responsibility to present unconventional-for-television individuals to the masses as reasons for doing so.

"He paints a picture with them more than anything else," said Scott David, Criminal Minds' casting director, who said he's "always on the lookout" for "a Gubler type."

David didn't have a very specific definition of a "Gubler type" beyond some adjectives: interesting, odd, weird, different. Finding talent for Gubler's episodes, he said, is "arduous."

"He doesn't like to accept anything less than perfect," David said of Gubler's casting choices. "His process is very, very deliberate, very calculated."

Erica Messer, Criminal Minds' showrunner, co-wrote the first episode that Gubler directed, Season 5's "Mosley Lane," in which the Behavioral Analysis Unit tracks down a couple that serially abducts children.

"You didn't want people that looked like they 'should be' on TV in the episode," she said. "He definitely chooses really interesting faces."

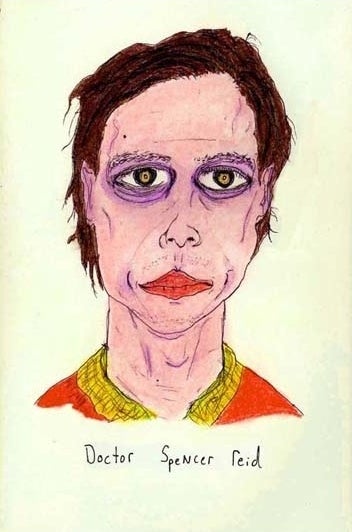

Gubler's choices extend to his own character; although he acts the part of the impossibly brilliant polymath Dr. Spencer Reid, he's always balked at the idea of playing him as a stereotypical nerd, and from Season 1 he's fought the image. "I'll never touch a computer, I'll never drive a car, I'll never hold a laptop, I'll never hold an iPad. My phone is from 1997," he said of the character. "I have a revolver instead of a Glock. I just wanted him to be out of step, sort of not in any era necessarily."

At left, Gubler as Dr. Spencer Reid. At right, Gubler's portrait of Dr. Spencer Reid.

"I don't even like calling him a nerd," Messer said of Dr. Reid. "In a way, he's almost a callback to nerds before (current) technology took off."

Dr. Reid takes after his portrayer: Gubler called himself "technologically kind of phobic," but instantly acknowledged irony of saying that when he has an active and somewhat bizarre web presence; he also acknowledged the oxymoron of using the internet to affect old-timey-ness, which he does frequently (he handwrites notes and posts them on social media sites, for one).

A bit out of step himself, Gubler is clearly drawn to a more grandiose aesthetic: He said he never imagined himself acting in a dark crime show, but might have guessed "fanciful horror movies" — he's more attracted to "lighter-hearted things," which jibes with his first role as "Intern #1 (Nico)" in the ever-playful Wes Anderson's The Life Aquatic in 2004. (In what seemed like dissociation from the "horrifying crime show," he did not refer to Criminal Minds by name for the first 49 minutes of the interview, calling it, rather, "the show I'm on.") Of the six episodes he's directed, five of them bear his distinct stamp — whimsically shot dream sequences, 1920s lamps, elaborate wallpaper, a sense of the vaudevillian; Messer referred to one as "a signature Gubler episode." The incongruous sixth is Paget Brewster's final episode, "Lauren," which has a more sober, less theatrical mise-en-scène, perhaps the perfectionist's concession to the gravity of a friend's departure.

At left, a vaudevillian dressing room from Season 8's "The Lesson." At right, a drawing room, complete with phonograph, from Season 7's "Heathridge Manor."

I asked him about making art in his downtime on the set he's worked on for nine seasons: "It seems like both filming in general and being on the same show for so long could potentially be —"

"Maddening?" he offered without a beat.

"Maddening, yeah," I said.

"It is for — I'm a control freak, which is why I love directing," he said. "I feel like I'm in a very rare group of actors who have played the same character for nine years… No one has ever explored — it's a very unique and lucky position to be in, but no one's ever explored how can you — there's no class on keeping that fresh or keeping your sanity amidst that very fortunate situation, so I see all my other projects — I don't know. I've always stayed busy, though."

Directing, he said, gives him the satisfaction he gets when he makes art — the ability to realize a more or less uncompromised vision, to not be "a tool in someone else's hand." The actor, in fact, doesn't like the idea of being an actor. "I always thought it's a profession that you have no control over," he said. "Like, as good as you were, you were still waiting for other people to pick you."

Gubler obliquely traces this preoccupation with control back to childhood; now tall and beautiful, he said he was picked on as an awkwardly proportioned child who loved magic. "I thank every bully I ever had because that's the only reason I'm here," he said. "I learned how to not be affected by it and triumph over it, and that made me — again, if I had any success whatsoever, it's because these people made fun of me."

It put "a drive" in him, he said, and in a way made him feel more secure in himself.

"Is that crazy? Crazy talk? The talk of an insane wizard?" he asked.

"You're saying on the one hand that it didn't affect you, but you're also saying that it's why you're here," I said. He did not have a response to the contradiction, but he recounted his first memory of being bullied.

"I remember a kid throwing an orange at the back of my head in Spanish class and calling me four-eyes, and I remember saying, I said, 'That's true, and I have two more eyes than you,'" he said. "I felt like it was better. If I have four eyes, I'm twice as good as you." If you don't let bullies affect you, he said, "their power is gone." You can't control their actions, you can only control your reaction, he explained. At the end of the interview, he said this opinion probably has a lot to do with the fact that he was only bullied for a few years before he went to a performing arts high school, "this magical realm of a school," he said, "that became a sanctuary for every not-quite-normal kid in Las Vegas," his hometown and a town where he still owns a home.

This magic he felt as a child has not yet left him ("I'm very similar to the way I was when I was 5," he said, laughing); he always wears mismatched socks because he is superstitious. This day he was wearing a polka dot sock on his right foot and a striped sock on his left.

"I've occasionally worn them matching, but something strange always happens on those days, whether it be spraining an ankle or messing up a knee," he said. One of these incidents (ankle-related) was caught on film in The Life Aquatic; his injury is in the final cut.

Gubler took the lesson to heart. "I was in a movie over hiatus where I had to wear matching socks — I had shorts on," he said. "I had them over mismatched socks. To protect, protect that."

His belief in the talismanic power of socks leads almost naturally to a world of spirits. He looked up at his friend's house as he described his own house in Los Feliz.

"It's sort of similar, actually," Gubler said, surveying the fern-surrounded home. "It's a little less castle-y. I don't know how to explain it. 1920s, some stained glass, haunted" — the last word in the sentence he said casually. "I like haunted things."

Haunted?

"Very haunted," he said. "Supremely haunted."

What have you seen there?

"I usually don't tell ghost stories in the daytime, but I'll make the exception," he said. He explained that when he first moved into the house, a friend from New York took a photograph, and when she developed it, she saw the face of a little girl looking out from one of his windows. Soon after, an Australian woman he'd just met saw a little girl's face peering out of the same window. Years later, Gubler saw the photograph. "Eerie," he said. I asked if there were anything else.

"That's sort of it," he said. "One night I was sleeping, when I first moved in. John Barrymore used to own the house. It was one of his places in the 1920s or '30s, and I woke up to the sound of ch — ch — ch —ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch — yayyyyyy! Like, kids cheering? I was like, what the heck is that? I put it out of my mind, and then it started up again. I realized, have you ever played the game Scattergories? It's like a board game?"

"Yes," I said.

"There's a timer that you have to wind, and the Scattergories timer was somehow, it was in a box on a shelf in the next room over, it was being wound and going off by itself, which I don't understand how that could physically happen," he said.

"Without a ghost," I said.

"It's not like a button, you know?" he explained. "It's an actual, you need gravity and force to turn it, but, so I ran upstairs. Creepy stuff like that. I don't mind it. I kinda like it." He smiled.

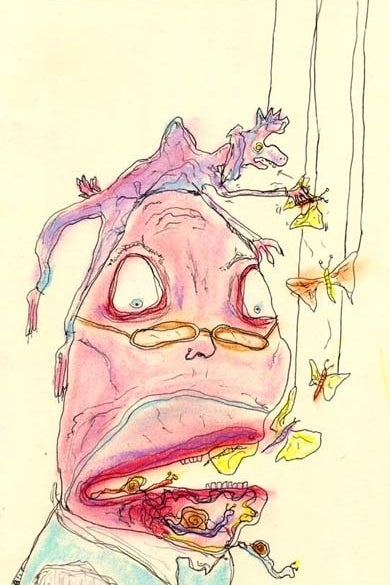

The painting at left is a man with a poodle on his head eating butterflies; at right is a painting of a brown dog with the words "Part Goat / Part dog / All cuddles" in the top left corner.

Gubler's enchanted world extends beyond the supernatural and into the banal. "I think sometimes as people get a little bit older, they become a little more serious or something," he said. "Everything's kind of magical to me still." He was watching me take notes when he remarked that he holds pens the same way. "Like velociraptor hands," he said.

"We have the same color glasses too," he said. "And we have the same haircut, kind of."

True.

"This is getting fuckin' weird," he said. "I like it."

My slant doppelgänger promised to haunt me after he died. "You're on the list now," he said. It was the first time I had met Gubler, but it was not the first time I'd been at this house. Sept. 15 at 1 p.m. I showed up at the gate and rang the buzzer. There was no answer, so I waited three minutes before ringing it again. (They did say "around 1," I thought.) Then I rang it again at 1:05. Then I buzzed every five minutes for the next 45 minutes, and then I left. As I was walking down the street, the car that had been parked outside the house (Gubler's car, I found out) drove past me, which made me suspect that he was, in fact, in the house the whole time. Perhaps the buzzer was broken, I thought.

At 7:22 p.m., Gubler left me a voicemail. "Hello, Ariane. This is Matthew Gubler. So sorry for the mix-up today. I understand you were at my house at 1, seeking the interview, which I mistakenly understood — I heard that you were available on the 21st and the 22nd, and I asked that we schedule it for Sunday, and I get the impression that someone, when I said Sunday, they didn't think that I meant the 22nd, they meant Sunday as in the next Sunday? Little bit of a crossed wire, sounds like. I pride myself on being the most punctual and the least flaky person in all of Los Angeles, so it kills me that you that you were at my door. I heard the buzzer — I heard someone down there, like, 'Who the fuck would be at my house on a Sunday?' Long story short, deepest of apologies. I will make it up to you; I'm sorry. Hope you had a good day despite being stranded at a weird gate probably kicking the ground, and this message is now becoming awkwardly long, annnnd etc. Anyway. Talk to you soon. Bye."

It was one minute and four seconds long, and the buzzer, apparently, was not broken. But when I showed up at that house a second time, he opened the gate immediately. Within two minutes, he asked to try on my helmet.

"I have a giant head; I doubt it'll — I'm pretty sure it won't fit, but I'm kinda just tryin' on a helmet." (He tries it on.) "Yeah, more like a yarmulke on me. Thanks for lettin' me do that." I told him "you're welcome," and an hour later he asked if we could trade glasses. His eyesight is very poor.

Toward the end of our interview, there was a long pause, and he said somewhat anxiously, "I feel like I sound like such a douchebag when I'm doing interviews, for some reason. Hopefully it's not translating that way."

"No, I don't think so," I said. I wondered then why he'd opened the gate at all, why a self-described control freak would allow anyone in, let alone a stranger with a tape recorder.

"All right. Thanks," he said. There was another pause; his self-confidence wrestled with his self-doubt. "Here's my impression of me doing an interview." He started speaking at a high pitch. "'Blah blah blah, I'm so weird, ooh look at me, wow, oh and I grew up, now I'm coooool, blah blah blah. Halloween, mismatched socks, yum yum, I love coffee. Here's a painting. The end.' Is that what it's gonna be?"