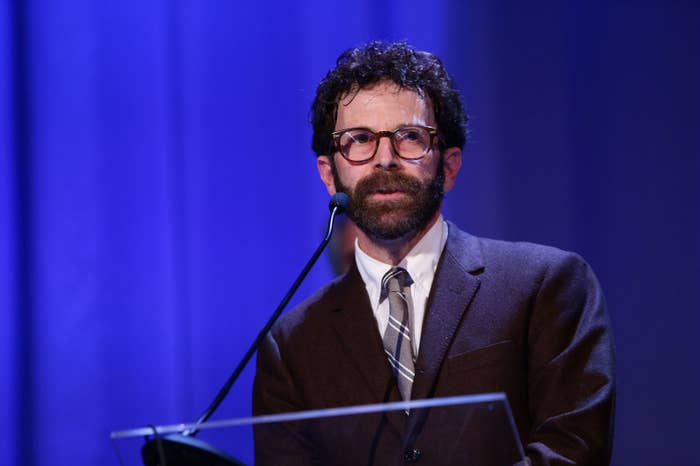

Not even Charlie Kaufman can dispel the myth that Charlie Kaufman doesn't do interviews. There's this 2008 video Q&A in which the filmmaker, making the rounds on behalf of his directorial debut Synecdoche, New York and clearly worn out, has a polite freakout when asked about his aversion to the process.

"I feel like I have this conversation with everybody I ever get interviewed with," he grumbled seven years ago. "You can look online and see 5,000 interviews with me. And for some reason, every time I sit down with someone, they say, 'You don't do a lot of press.' There's all this stupid mythology about people that just gets perpetuated constantly. People decide something about someone and it doesn't ever change."

That mythology has Kaufman as some dyspeptic, eye-contact-averse, capital "G" genius sitting alone in a room scripting the most iconic films of the last decade — films like Adaptation. and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotlight Mind. But he's not. Nor did he burst onto the scene as some outsider screenwriting savant in 1999 with his first feature, the Spike Jonze-directed Being John Malkovich.

He actually wrote successfully for television for years on cult series like The Dana Carvey Show and total normal ones like Ned and Stacey before making a name for himself in film with his penetrating portraits of loneliness, existential crises, insecurity, mortality, and longing, all filtered through stories that are witty and surreal.

If Kaufman seems like he should be reclusive and aloof, it's because his work is so singular and uncompromising and so great that it's tempting to think of it as something that comes from someone incapable of doing anything but turning it out. But all the mystique in the world couldn't rescue Kaufman from the very regular and frustrating Hollywood problem of not being able to get funding together for a new project. Being the finest screenwriter working today (sorry, Sorkin!) isn't meaningful when your work doesn't fit into the new definitions of commercial, and Kaufman had to look outside the usual structures to get his new film made.

"I've been busy," he points out to BuzzFeed News when talking about the seven years since the critical hit and financial flop that was Synecdoche, New York, even if little he's done has seen the light of day. He shot a pilot for FX, How and Why, that wasn't picked up, worked on a novel, and wrote three features, one of which, a musical Frank or Francis, was set to star Jack Black, Steve Carell, and Nicolas Cage before it fell apart. And then the stop-motion animated feature Anomalisa, produced by Dan Harmon and Dino Stamatopoulos' Starburns Industries and based on a play Kaufman wrote, came into being with the help of some crowdfunded seed money.

Kaufman and his Anomalisa collaborator and co-director Duke Johnson are biding their time in the bowels of the Elgin Theatre as their movie has its second screening at the Toronto International Film Festival. Kaufman, 56, is elfin, curly haired, bearded, and careful with his word choice, sometimes pausing and sighing as he deliberates on the right ones. Johnson is 36 and could pass for a decade younger.

The collaborators hadn't met before Starburns Industries matched them up for the project, though Johnson, who directed the stop-motion Community Christmas installment and multiple episodes of the Adult Swim comedy Mary Shelley's Frankenhole, was already a big fan of Kaufman's. Johnson's boss, Community creator Harmon, is a fan himself, and Kaufman confesses to being "thrilled" to have been a reference on the series.

The two are in the kind of good mood that a rapturous reception at Venice and Toronto and a surprising acquisition the night before by Paramount Pictures will earn you. After all, three years ago, Anomalisa was a Kickstarter campaign; now it'll be released in theaters Dec. 30, and seems a shoo-in to valiantly go up against and be inevitably clobbered by Pixar's Inside Out in the animated feature Oscar category.

Anomalisa is Kaufman's least fabulist film — there are no trips into the head of an acclaimed actor, no feral humans living in the woods. There's just Michael Stone (voiced by David Thewlis), customer service expert, and the anonymous confines of the Cincinnati hotel in which he's staying, having been booked to speak at a conference. Michael has a wife and child back in Los Angeles, but becomes entranced by a woman named Lisa (voiced by Jennifer Jason Leigh) he's convinced is special and the solution to his own feelings of isolation and dissatisfaction.

Kaufman hadn't conceived of the story as one suited to stop motion. It wasn't a project he conceived of for film at all, and he was initially resistant to the idea of adapting it. "I hadn't thought of it as anything live action or animation. It seemed to me that it shouldn't be either — that was my initial reaction," he says. Kaufman first wrote Anomalisa as a "sound play," meant to be performed without staging or a set, the actors reading the lines off of scripts on music stands.

"I had designed it so that things that would be alluded to in the dialogue would not exist except in the audience's mind," he says. "I thought I'd be giving away, or rather having to throw away, a lot of stuff that I really loved about the play. Which ultimately I did, but then it became its own other thing."

"It's not theoretical for me. I'm not going, OK, now I need to address what storytelling means in the modern age."

What was a symbolic but also not uncommon theater device involving Tom Noonan playing multiple characters in the play became the guiding visual in the film, a representation of Michael's depression that, like all of Kaufman's work, is funny, unsettling, and ultimately terribly sad.

It's a choice that's better left undescribed — the filmmakers have been so coy about imagery that the photo at the top of this article is the only one they've made available so far. But it's an approach that is hard to imagine working without animation. "It became serendipitously thematically important to the telling of this story once we started to think about what that is," Kaufman says. "Now I can't see it being done any other way."

There are other things that transmuted from jokes into something deeper when shifted from stage to screen. The movie, for instance, features the most explicit puppet sex scene since Team America: World Police, though it's one that's tender and awkwardly realistic. In the play, it was two seated people making sex sounds. "It was met with laughter onstage, which we knew was going to happen," Kaufman says of the scene. "But the whole thing became very different. Lots of things where the aspect of commenting on it that was just inherent to the play was taken away."

That tendency toward meta-commentary is something Kaufman's famous for — never more so than in Adaptation., in which self-awareness weighed on its protagonist, who shares a name with the writer, like an anvil around his neck. But it's not something he likes to intellectualize. "It's not theoretical for me. I'm not going, OK, now I need to address what storytelling means in the modern age," he says with laugh.

"I'm always thinking that this is a thing that helps with whatever emotion I'm exploring. For me, that's what it is, and if it isn't that, then I don't want to do it. It isn't the thing that comes first. I like to leave myself open to the irrational — I feel like that's fruitful for me in my writing, because there is a cornucopia of metaphorical imagery in dreams that I find fascinating."

Anomalisa features some of Kaufman's least self-reflexive work, his most grounded in the crushingly mundane — so it's fitting that someone who started his career with a movie about a puppeteer, Being John Malkovich, has now made one in which there are only puppets, a throughline Kaufman describes as "a happy accident." But even as the characters move and react in painstakingly realistic ways, they're designed to put their artificiality upfront with visible joins in their faces. It is, undeniably, Kaufmanesque.

"Almost all of stop motion animation paints out those seams," Kaufman says. "We were adamant that they would not be painted out. We're doing this thing that's handmade, that's so time-consuming and intricate, and that's the beauty of it. To then paint that out with a computer just seemed wrong."

"We wanted to keep the seams."