Has anybody heard anything?

A long string of comments on Aubrey’s Facebook page asked the same question. I stood outside of the DMV pushing refresh on my friend Torrey’s iPhone. Somebody said they heard about police action near the Golden Gate Bridge, but that was it. At the top of Aubrey's feed, she had posted a picture of the choppy gray water running beneath the bridge, captioned with her words:

Being trans sucks!

I handed Torrey back the phone — mine was dead in my pocket — and we got on the bus northbound.

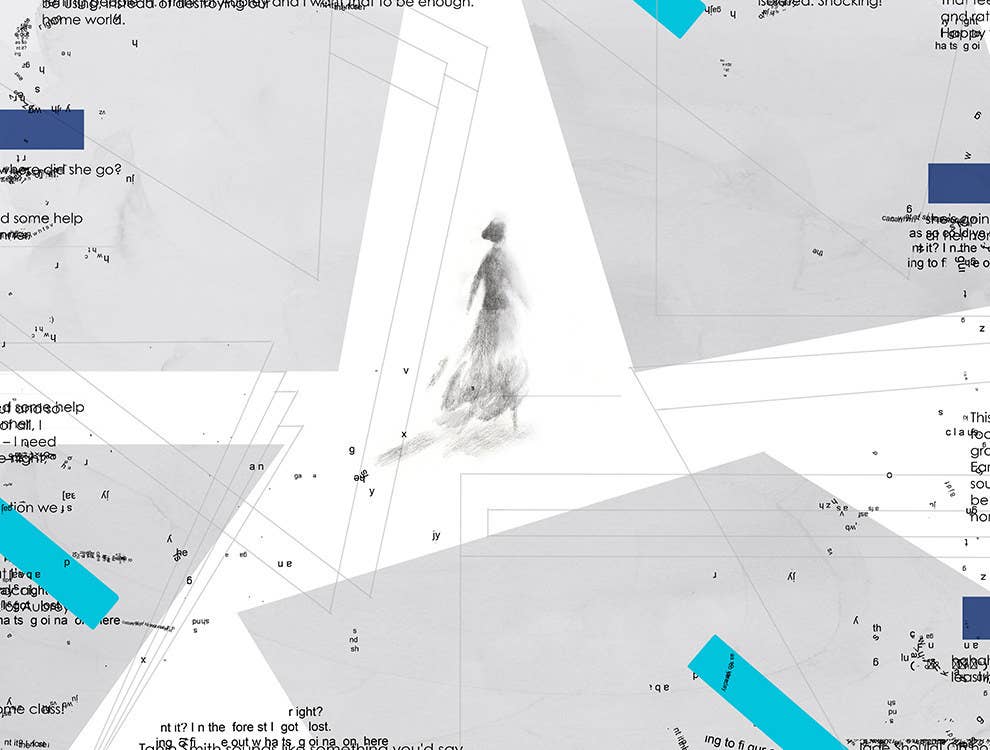

Digital information was the only way I knew Aubrey. Aubrey, who typed in the corner of my screen and left pictures of Pusheen the cat; Aubrey, who asked out boy-mode me in my last profile picture before transition as a joke; Aubrey, who would definitely be at the third GaymerX conference if I decided to travel down to the Bay. But now she was silent, Facebook was silent, and the only thing that could tell me whether Aubrey was alive or not was my intuition. Refusing to feel, I formed a compartment within myself – a box of cold wood that I crouched into, and waited.

As a child, I learned how to make these compartments and hide inside them. They allowed me to stay at the dinner table when I was being screamed at, or look into the mirror without really seeing myself. The dark arts of dysphoria and depersonalization is something I’ve tried very hard to unlearn, and my transition as a transgender woman — which has now been happening for two months — has been one of the ways I've searched for reintegration: a way of living without boxes and compartments.

But walking through downtown Seattle, I didn’t want to bring those pieces together. I needed somewhere to be other than myself.

I went into a coffee shop to boot up my computer. Still nothing on Facebook. I started to write a cover letter and revise my resume; a few minutes later a new update appeared on Aubrey’s status. The police had identified her body in the water. I sent a text to my friend Andrew — can I come over, I need to come over. An hour later, Andrew let me in and I climbed the stairs two at a time. I told him that I would like him to tell me it’s OK to cry. He led me to his couch and told me it’s OK to cry. And then the floor broke down and I cried, and cried, and cried, and cried.

When I stopped crying, all I could see was the image of the water running beneath the Golden Gate Bridge. Aubrey was gone.

For a long time, the internet was the place I went to be alone. It was this weird, large cavern I could wander around in, where new parts of me could emerge from the shadows. I went online to experience the thrill of what danah boyd calls writing ourselves into being.

As a middle-schooler, I developed a weird sense of confidence in my ability to make something out of nothing online. I parlayed my childhood dream of writing games into a very short-lived stint writing the backstory to a Swedish MMORPG (the lead designer wrote me an email telling me my story was “awful,” which, at the time, I was 100% sure he intended to write “awesome” but had mistranslated into English.) By freshman year in high school, I had fallen in love with LiveJournal, and wrote endlessly about my ambitions in music, my father’s resentment, and a girl I had dated briefly and then romanticized in absentia for an embarrassingly long time. I found a loudness and a playfulness and an anger and a femmeness that I couldn’t yet integrate into my day-to-day life.

I relied upon those private digital spaces, where nobody was keeping track or connecting the dots. The semi-anonymity gave me relief. I was terrified somebody would try to put the parts together for me.

In college, a friend of a friend opened up my laptop as we prepared to host a party. I heard my voice and immediately recognized the opening line in my YouTube video on Myers-Briggs and my struggles with social anxiety. I ran across the room and shut the laptop. For years, my friends would occasionally bring up the video and try to nudge out of me what it was about, what I was hiding. They asked with kindness and affection — but they didn’t realize how important that boundary was to me. How important having that extra space of working-through was to keeping myself ordered and comprehensible, so that the urges to destroy myself wouldn’t swell high enough to wipe me away all at once.

I decentralized and anonymized. I built compartments.

When I couldn’t cry any more, Andrew suggested that we leave the apartment and go somewhere. I washed the smeared makeup off of my face and Andrew drove us across the bridge to West Seattle.

Andrew and I had moved to Seattle two months ago from opposite sides of the country. He was an old friend from college — we had met when he visited my roommate to play music six years earlier — but we didn’t expect to end up in the same place at the same time. He is the only person who knew me before transition who I see on a regular basis.

That night we talked and ate lo mein and somehow laughed a lot. At one point, Andrew asked, "What do you think about bowling?" Again I laughed — hard this time — and realized, yes. I desperately wanted that. We walked a few blocks, rented shoes, and started to bowl.

That night was full of an impossible presence. As time passed we would grow quiet and my thoughts would drift back to Aubrey. Sometimes I didn’t need to say anything. But other times I had to ask Andrew, "How do we keep each other safe? How the fuck are we supposed to do that?"

I knew Andrew couldn’t answer this question for me — I asked it of myself, too.

For years, I hung out in a pre-transition internet that is familiar to many trans folks. I re-read the same threads again and again on /r/asktransgender; I watched “transition timeline” videos and Q&As on YouTube; I found PDFs of books by Kate Bornstein and Julia Serano. In 2012, I asked in an AskMetaFilter thread how to build the confidence to incorporate more femme elements into my gender presentation — and a year later, I asked the same question again (I had only bought colorful Happy Socks and lost my nerve with the rest).

It was important to me to spend time in these spaces, while also managing exactly when I emerged, and to whom, and in what light. In one discussion thread, after I asked whether you can be transgender if you talk in a deep voice when tired and enjoy hanging out with guy friends, a veteran who had transitioned after her service expressed exasperation and suggested that I might find the site www.amitransgender.com helpful. I laughed and then I felt ashamed. I didn’t post another question for months.

Months turned to years and I was still on the same pages, reading the same usernames. On the forums, I started to think about the other people lurking behind their usernames. I noticed people younger than me and more doubtful, asking questions from a point of view I recognized as my own just months before.

It was around this time, summer of 2014, that living in compartments became untenable. I started bringing parts of me together in the daylight: the femme parts, the expressive and alive parts. I dressed differently — first at home, then with friends, and then at work. When I noticed the sense of lightness spreading through me, and how wonderful it felt, my transition became unavoidable.

I came out to my family in October, my friends in November, and started hormones on Dec. 8. Shortly after, I met Aubrey.

She reached out to me first. I had just joined a handful of trans-related groups on Facebook, where it was much more difficult to imagine yourself as an anonymous username. I had posted a question on a gaming for trans folks group, and Aubrey had reached out to me in a private message.

Aubrey was sweet and emotive and silly. She showed up in my Facebook Messenger box in January, just as I had moved 3,000 miles to Seattle with no job, housing, or plan. She appeared often and I tried to do the same for her. I once messaged her from Elliot Bay Books when I sat in the café full of frustration. The barista was a slender, hip woman; when she had taken my order, she turned away and yelled, so the whole area could hear, “HE wants an ICED TEA.” I sat in the café corner and felt stupid and clumsy and Aubrey encouraged me — you don’t have to just accept that. I got up and I spoke to the barista, who started offering some vague words about being an open-minded person and then apologized for having a bad day.

It was the first time in my life I had openly corrected somebody else when hearing that pronoun. Aubrey text-giggled and sent me cat stickers to celebrate.

It was also the first time I had shown my shame to a friend as I was experiencing it. And that friend had told me, Hey, you don’t have to hold it inside yourself. You have a right to take up your space. I kept the window with Aubrey’s chat open long after she signed off.

After Aubrey died, posts circulated online. “TWOC Aubrey […]’s suicide from the Golden Gate Bridge caused hardly a ripple.” The Tumblr posts that included photos from Aubrey’s Facebook were taken down, but others appeared quickly. People wanted to tell Aubrey’s story. She had worked with queer and trans youth, and served as an organizer and leader even while still recovering from a prior attempt. She had bounced from foster home to foster home over the years earlier. I learned in one of her last posts that she had been raped and assaulted, and that in the middle of unemployment and homelessness last fall she had contemplated detransitioning. I knew Aubrey had suffered, but the degree to which she had been let down again and again by the systems set up to serve her was devastating.

Katie, a friend of Aubrey’s in Oakland, found me on Facebook after reading my comments on her last status and sent me pictures taken in the week after her death. One showed a collage made by the queer and trans youth with whom Aubrey worked. I read about Aubrey’s awkward laugh, which I had never heard. It meant so much to have these few .jpgs and sentences. For an instant, I could see Aubrey through the eyes of other people who loved her, and who spent a kind of time with her that I would never spend.

As the posts about Aubrey spread across social media, the cry of anguish rang loudest — the anguish of losing yet another trans woman of color. Online acquaintances shared and reposted, and I looked again and again at that last photo of the water beneath the bridge. It hurt so much that my friend who sent those silly Pusheens was gone, and in her place were digital traces of immense suffering — a suffering that still, somehow, “caused hardly a ripple.” Where did she go?

I read in one of the posts about Aubrey that she had been texting with a friend only minutes before ascending the bridge, and that she had said she was going for a walk. When I think about the texts, every part of me wants Aubrey to have shown up in that pain, however enormous. I wish I could have created that space for silliness and devastation and all of the misshapen broken things, spread a little blanket out on the lawn for it all.

It’s not always clear how we can do that for each other, especially over digital spaces. I continue to regularly post in Facebook support groups, but they can be difficult environments. Call-outs are frequent, cliques formed and hardened. A text post by a new member struggling with suicidal thoughts can go unanswered, whereas a selfie posted by a well-connected regular receives hundreds of likes and comments. When I think about the groups as a whole, I find the individuals again receding to a background — people become nodes in a network, and pain and dysphoria act as this electric current leaping from point to point. It’s easy to become overwhelmed, and to lose the habit of connecting as people. I look through conversations in the groups and I’m afraid to make myself visible again, knowing that the first person I really let in is gone.

But I keep showing up. I recognize, amid the scuffles and imperfections, a community of people attempting to construct new ways of being there for each other. I recognize what has been so beautifully named “righteous femme anger,” and in it the resistance against transmisognyny, white supremacy, and social exclusion. I see myself in the newcomers who struggle to take up their space. I see what we share, unavoidably and wonderfully, everywhere.

I make friends when I can. After 25 years of existing online as a mostly-lurker, I find myself exchanging packages and discussing dogs with JayCee in Minneapolis, or comparing selfie notes with Sophie. Through these relationships, I learn to manage myself less closely. I am still protective of alone time and processing in my own space, but I let myself be seen too — my ritual unlearning of the old dark arts.

Shortly after I met Aubrey, I went on my first date after coming out. My date was a singer in a metal band, tall and pale and wearing a beautiful dress. I couldn’t believe how wonderful it felt — scary and wonderful — to exist for a night in this femme space of romance, talking about Wicca and video games and our lives in transition while moving our bodies closer and closer. On the bus home, both of us a little tipsy, she leaned against me and handed me her phone. “I love whoever made this,” she said, typing www.amitransgender.com into the browser and laughing. And I laughed too, delighting in reading it from the other side — and with somebody else who got it, too. We didn’t need to explain it to each other.

I never told that story to Aubrey, but I wish I had. I know she would have understood.

Aubrey is gone. There is so much I’m angry about and so much I don’t and won’t ever understand. Most of all, I want to know how we can keep ourselves alive — I need to know. Calling TransLifeline in the middle of the night, speaking against the discrimination and annihilation we face, checking in on Facebook support groups, saying I love you to a trans woman, celebrating righteous femme anger, and sending cat stickers are what I’ve found so far — and until I find something unequivocal, something sure, I’ll keep letting people in. I think of Aubrey and I want that to be enough.

A few days before she died, Aubrey posted a photo of a group of girls, sitting together and smiling in a bedroom. They were her sister and her cousins. In the description Aubrey wrote that she loved them, and that although they rejected her she hoped, one day, they could accept her as a girl and she could join them. Aubrey found ways to love in the middle of pain. I don’t think there’s any higher praise that can be written about a person than that.

We can make space for each other to be integrated, whole beings. We can say fuck no to compartments. We can say yes to being all of ourselves, wherever that takes us.