England, what have you done to make the speech

My father used a stranger at my lips,

An offence to the ear, a shackle on the tongue

That would fit new thoughts to an abiding tune?

Answer me now. The workshop where they wrought

Stand idle, and thick dust covers their tools.

The blue metal of streams, the copper and gold

Seams in the wood are all unquarried; the leaves’

Intricate filigree falls, and who shall renew

its brisk pattern? When spring wakens the hearts

Of the young children to sing, what song shall be theirs?

– R.S. Thomas

Finding R.S. Thomas’s poetry in a city like Nagpur is a rare thing. For me, it was a gift.

I discovered Thomas’s poetry in 2012 when I was in the second year of my bachelor’s degree in Nagpur, studying English literature. Before I could read his poems, I was introduced to his biography by one of my friends.

But what’s so special about Thomas?

My first learning about "language as politics" came from him and his poems.

English came to me as a fascination, but I was unaware of the roots of that fascination.

The school I attended was a Municipal Corporation school – during the rains, roof tiles often leaked and that would become a reason for a holiday. English was seen as taboo and the language of elites, hence not much stress was laid on teaching it to students.

After school, I lost almost five to six years of my life, working for money, dropping out of one course after another. But my fascination with English only grew throughout this time.

I eventually decided to study English literature, fully knowing that it might never offer me a career. Yet I was satisfied as the course offered me readings and references that would help me in learning the language.

But until I started my master's in 2013, I was unaware of the fact that I was just reading and learning about stories of people in English and not the language itself. I read my first English novel in 2010 – Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. I read it thrice, back to back, for the simple reason that I didn’t understand a bit of it in my first reading.

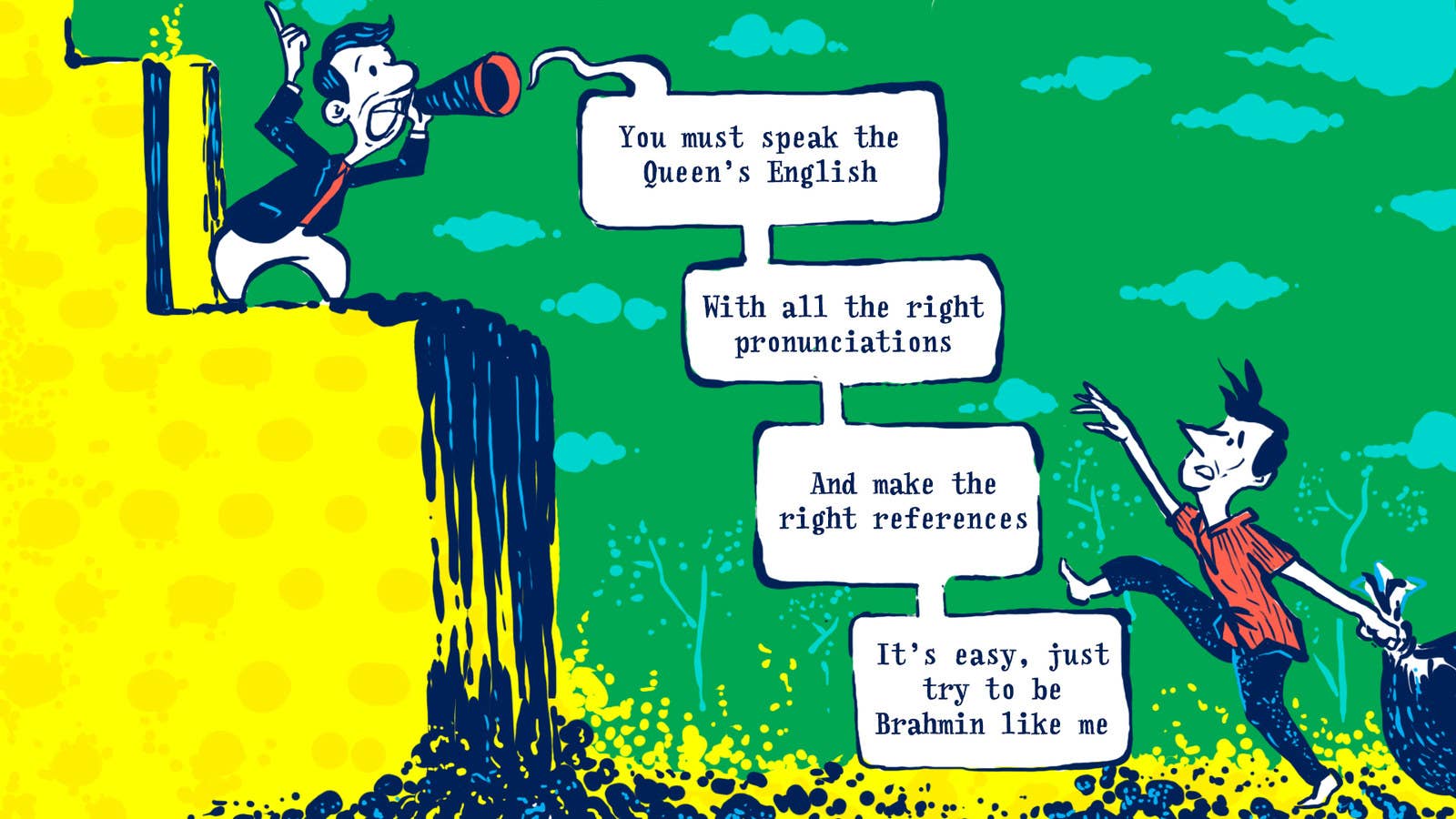

For two years, a Brahmin professor taught me English literature. On one not-so-fine day, I shared my experience with her of reading a novel, in English. Uninterested in what I spoke, she corrected me on a grammatical mistake from my conversation in an authoritative voice.

I felt belittled. My understanding had been reduced to errors in grammar.

After this incident, I read more and more, voraciously, and I would read anything and everything that was available to me in English. This was also the time when I started to write poems in English.

For a long period of time, however, I was brooding over that incident, thinking about the connection between language and knowledge, and whether language is for man or man is for language.

It was only after reading the poems of Thomas that I was so intelligently, if not poetically, introduced to the elements of power and hegemony in the game of language and knowledge.

Thomas was a Welsh nationalist who hated the anglicisation of his language. But he wrote in English. Often, I could see his anxiety and subtle dislike for English in his poems. His poems described how disastrous English has proved to Welsh history and how he had always longed to write in Welsh but couldn’t.

I felt close to his anxiety.

And I also felt his dilemma of having written in English throughout his life.

Thomas's poetry introduced me to the elements of power and hegemony in the game of language and knowledge.

For a first-generation learner like me, a Dalit, it was not very difficult to decipher this dilemma, simply because I knew the risk of learning a language that wasn’t mine and in which I had not found myself yet. This made me restless about the question of language.

This restlessness only grew stronger thereafter. In 2013, after finishing my bachelor’s degree, I came to Mumbai to pursue a master’s at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), one of the premier institutes for social sciences in India.

The medium of instruction in TISS was English. Students came from various caste, class, and religious backgrounds and people like me were suddenly pushed into Western discourses, mostly shaped in and around the English language. It was assumed that everyone would understand what was being taught in English. And if they failed to do so, they were confronted with the feeling of perceiving themselves as failures as compared to the other students.

Within the caste/class diversity of students in TISS, students from Brahminical and elite backgrounds to whom English is an inheritance always dominate the scene, no matter which religion they belong to. This sense of domination is no doubt shaped by their upbringing.

During the course of four years in this institute, I met several Dalit students whose knowledge and clarity about society was incomparable, yet in examinations and in achieving foreign scholarships, mostly the Brahminical students took the cake just because they had the language.

I was on many occasions told that I made grammatical errors in what I said, that my pronunciations were incorrect, and they subsequently dictated and demonstrated the correct pronunciations.

This anxiety to "correct" me and many Dalits like me when it comes to English was nothing but an exercise to use the position of domination, I felt.

Their language was their domination.

These instances also forced me to become a recluse during my master's. I developed an aversion to such discriminatory spaces – an aversion I seemed to share with many fellow Dalit brothers and sisters in the institute.

The dissemination of English in the colonised caste society of India readily offered an upper hand to Brahmins because of their proximity to the British, by which, after 1947, they cemented their position as the English pundits in India.

Bernard Cohn in his book Colonisation and its Forms of Knowledge wrote: “What knowledge the British had of learning and religious thoughts of the Hindus came from discussion with Brahmans and other high-caste Indians, or from Persian or 'Indostan' translation of Sanskrit texts.”

Brahmin proximity to the British, to English, and the process of manufacturing "knowledge" about caste-society won them a position after 1947 that let them dominate and hegemonise the discourse of English in India. A simple glance over English departments in Indian universities across every state shows the overwhelming presence of Brahmins, both as students and professors. This explains to us how English, as the language of British, always helped Brahmins to enjoy the benefits of the domain of academia in and outside India.

I wrote in an article published in Roundtable India in 2014:

In my conversations with a classmate who belonged to a privileged background, Upper Caste Muslim girl, a graduate from an elite women's institution in Delhi, I found a helpful friend to repair my pronunciation of English words and correct my grammatical mistakes too. Eventually, however, this seemed to transform into her moral task.

At first, I found nothing odd about it. But when it switched to a mode of the subtle practice of expressing linguistic superiority, I began to perceive a sense of alienation and a waning of confidence in our intellectual conversations.

Her inadvertent or perhaps even intentional superiority was most likely derived from the socio-cultural values she had deeply internalized from her background in the exclusively English speaking circle of elitist and esoteric institutions.

"Is it wrong to pronounce English words differently, especially when you are not convent educated?" I would ask myself then.

Later on, I realised that the subconscious will of maintaining linguistic hegemony, to deoxidise Dalits in their intellectual pursuit, so as to create a socially exclusive class of privileged ones, is widespread around us. This ultimately leads to the exclusion of Dalits from gaining a philosophically contesting position in the same language- English.

In what is commonly understood as pop culture in India, you won’t find such instances of discrimination based on language as language is controlled and dictated by the Brahminical classes who also rule the media that manufactures popular culture in India.

In what is commonly understood as pop culture in India, you won’t find such instances of discrimination based on language, as language is controlled and dictated by the Brahminical classes who also rule the media that manufactures popular culture in India.

According to a few significant anti-caste observers, Dalits in English media in India are almost absent. In this context, the journalist Sudipto Mondal wrote in Al Jazeera, “There are still more openly queer people in English journalism than people who admit to being Dalit. Indian journalism is so mind-numbingly upper-caste that the mere act of 'coming out' by journalist Yashica Dutt was celebrated as a milestone in the quest for caste diversity.”

Language is controlled and dictated by the Brahminical classes who also rule the media that manufactures popular culture in India.

This explains the trajectory of discrimination with the English language in India as another tool in the hands of upper castes, especially Brahmins, to dictate and define "knowledge" for others.

This is the case with Marathi too. The Marathi I speak at my home is completely different in its vocabulary, accent, tone, and essence than the Marathi I was taught at the school. That was the Marathi that the ruling Brahminical class, through the state mechanism and school, inculcated in me.

It is the same with any language in India.

When Namdeo Dhasal’s Marathi-language Golpitha, his first poetry collection, was published in the 1970s, it generated pangs of hatred in the hearts of Brahmin writers as Dhasal so powerfully managed to articulate the language of the people he grew up with. It was a daring act.

His was a Marathi shaped by his history as Dalit, undefiled by the Brahminical state and challenging it. On the one hand, Thomas’s problem with English and his yearning to write in Welsh tells us the coercive nature of English at the hands of the ruling class and how it thwarted his aspiration to find and express himself in Welsh.

On the other hand, Dhasal’s reinvention of Marathi for Dalits is a symbol of assertion that we rarely find in the discourse of English, at least in India.

I remember once I was talking to a friend, and he said, “Language, more than a means to communicate, is the mind itself. It’s not whether we understand English or not. The question we should ask is whether English understands us or not.”

Lately, as I become more and more involved with English through writing, I find myself going far from the language I inherited, the language my forefathers spoke and bequeathed me, the language of their suffering and their joys, the language of their struggle and victories.

Language does not work by itself; language works through people. Therefore, looking at the history of English and India, Brahmins not only possessed the language but, over the years, became the dictators of it. This is an oppressively phenomenal situation for Dalits. To understand this oppression, I take refuge in poetry:

My father sang me

In a language his father taught him

Hence, in it his rage had clarity

His love was sublime.

But I grew up much greedy

I wrote in English and kept on writing;

Later, father’s words turned voiceless to me

I turned deaf to his song, I grew up mean.

Today, I imagine

If I have a son or a daughter,

What song shall I sing to them?

Precisely, in what language shall I sing?